Professor Alfred Jeyaratnam Wilson (1928-2000)

My Impressions

by Sachi Sri Kantha, June 8, 2012

|

I was reluctant to write this book, and for a long time after 1983 I could not resolve the matter in my conscience. A major factor was that I was close to President J.R. Jayewardene in the critical phase from 1978 to 1983. But as I kept reading with horror the operations by security forces of the island state, I realised I could no longer be a silent witness. The community of scholars interested in Ceylon had to be told what happened when I was intermediary in the Sinhalese-Tamil dispute in the years 1978-83. I realised too that an analysis of the political process of which I had an inside track since the island’s independence in 1948 would place in context my role in the years concerned. |

The twelfth death anniversary of Professor Alfred Jeyaratnam Wilson passed by quietly on May 31st. Until now, I had refrained from writing about my interaction with one of the foremost political scientists produced by Sri Lanka in the 20th century. So, I take this opportunity to reminisce a little.  The fact that his death anniversary falls on May 31st is coincidental to the 1981 book burning event of Jaffna perpetrated by the Sinhalese goons and thugs, akin to the 1933 bibliocaust conducted by the Nazi sympathizers, should not be forgotten. Until now, I had written regularly on this 1981 book burning event for umpteen times to this site. The four part series, ‘Perversity of Pyromaniacs’, which I contributed in 2006, is probably the lengthiest to document this pathetic episode. The fact that his death anniversary falls on May 31st is coincidental to the 1981 book burning event of Jaffna perpetrated by the Sinhalese goons and thugs, akin to the 1933 bibliocaust conducted by the Nazi sympathizers, should not be forgotten. Until now, I had written regularly on this 1981 book burning event for umpteen times to this site. The four part series, ‘Perversity of Pyromaniacs’, which I contributed in 2006, is probably the lengthiest to document this pathetic episode.

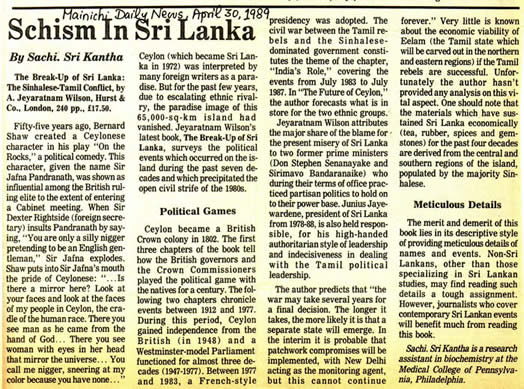

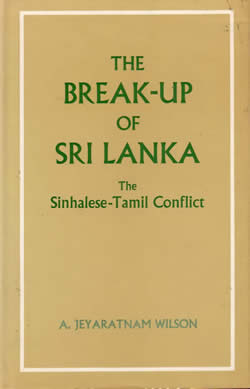

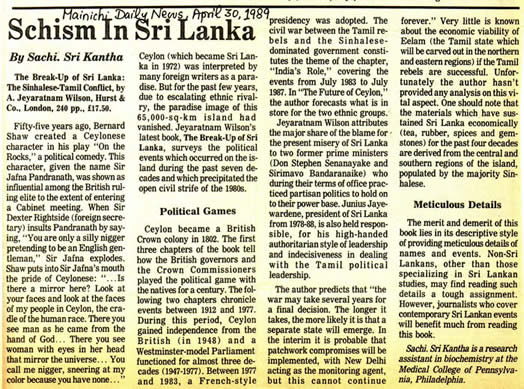

To commemorate this 1981 event equally, I present one book authored by Prof. Wilson in 1988. It was The Break-Up of Sri Lanka: the Sinhalese-Tamil Conflict. My brief review (~500 words) of this book appeared in the Mainichi Daily News (Tokyo). I present a scan of this review nearby. To remember Prof. Wilson, I reproduce the preface he wrote to this book in March 1988, excluding the last two paragraphs (that incorporated acknowledgments). The words in italics, are as in the original.

“I was reluctant to write this book, and for a long time after 1983 I could not resolve the matter in my conscience. A major factor was that I was close to President J.R. Jayewardene in the critical phase from 1978 to 1983. But as I kept reading with horror the operations by security forces of the island state, I realised I could no longer be a silent witness. The community of scholars interested in Ceylon had to be told what happened when I was intermediary in the Sinhalese-Tamil dispute in the years 1978-83. I realised too that an analysis of the political process of which I had an inside track since the island’s independence in 1948 would place in context my role in the years concerned.

I have used ‘Ceylon’ advisedly because that is how the country was called for well over 150 years before Sri Lanka was unilaterally introduced into the vocabulary of international usage in 1972; this was done without the consent of the principal minority, the Tamils, the community to which I belong. Sri Lanka is used in the title to convey to readers evidence of the disintegration of the polity under its new name.

My considered view is that Ceylon has already split into two entities. At present this is a state of mind; for it to become a territorial reality is a question of time. Patchwork compromises, even if underwritten by New Delhi, are passing phenomena. The fact of the matter is that under various guises the Sinhalese elites have refused to share power with the principal ethnic minority, the Tamils. The transfer of power by Britain to the Sinhalese ethnic majority in 1948 brought in its wake an unfortunate train of events which can best be described as a loss of perspective on the part of the Sinhalese political elites. Their anxiety for power led to the abandonment of principle.

My interpretative analysis is based on inside knowledge of political events, which in turn is derived from my acquaintance with many of the political leaders of the Sinhalese and Tamils and important members of their respective elites. Most instructive, however, were two leading statesmen. One of these was my father-in-law S.J.V.Chelvanayakam, who led a revived Tamil nationalism and with whom I was in frequent contact from 1948 till his death in 1977. He was at the centre of events as a leading Opposition figure.

The other was President Jayewardene, whom I came to know intimately in the years 1978-83. He was in many ways on a lonely eminence. He does not have a helpful cabinet and came to office very late in his life. Whenever I was visiting Colombo from Canada, I spent much time with him, sometimes every day. I travelled about Ceylon with him, and was occasionally his only companion. We had wide-ranging discussions, but I have only referred to selected matters relevant to this book because of confidentiality and respect for our relationship in those years. Mrs Jayewardene, a gracious lady with considerable political acumen, joined us at times in our discussions.

I have tried to treat my subject in consonance with my academic calling, and thus with my conscience. I have presented the facts in a historical frame of reference. The authenticity of many of the facts can be verified in due course through the archival arrangments I have made with Columbia University in the city of New York. There is a proviso that the documents be made accessible after a thirty-year time lapse. For the rest I have depended on my own notes and on primary and secondary sources.

We live in a Third World largely of artificial sovereign geographical expressions. The proliferation of mini-states is inevitable. Ethnicity transcends barriers of region, religion, class and social distinctions. Leaders and political parties in these postcolonial states, whether democratic or authoritarian, respond to pressures from their ethnic groupings. My view of the future is reinforced by the certainty that political problems owe their existence to circumstances that are of more than 2,500 years’ standing* especially when the political processes have been modernised. When the geopolitical situation has also been activated, the hopes of an island unity are dim.” [*Foot note: Apart from the political activities of the Buddhist clergy in independent Ceylon (and in the days of the Sinhalese kingdoms), D.C. Wijewardene’s The Revolt in the Temple: Composed to Commemorate 2500 Years of the Land, the Race and the Faith, Colombo, 1983, conveys the depth of Sinhalese Buddhist feeling on the need to safeguard the Sinhalese people and Sinhalese Buddhism.]

One should remember, when Prof. Wilson wrote this on March 1988, President Jayewardene was holding court in Colombo, and LTTE was engaged in a war with the Indian army (euphemistically called, Indian Peace Keeping Force). SLFP and JVP opposed the presence of Indian army in Sri Lanka and was engaged in extra-parliamentary agitations. Though all (excluding the rabid colonialists) agree with the sentiments expressed in the first sentence of the last paragraph quoted above, many (holding the power whip at the United Nations) did (or do) not agree with the sentiments expressed in the second sentence. But, later events did prove Prof. Wilson’s forecast in the European political theater. In 1988, there were Soviet Union and Yugoslavia. In 1990s, both disintegrated into smaller states.

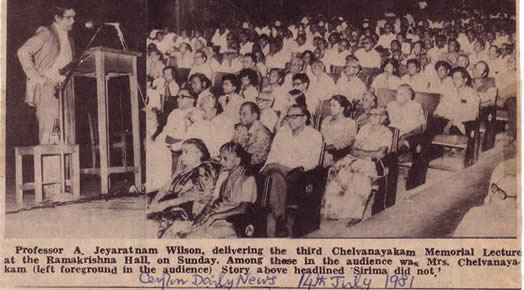

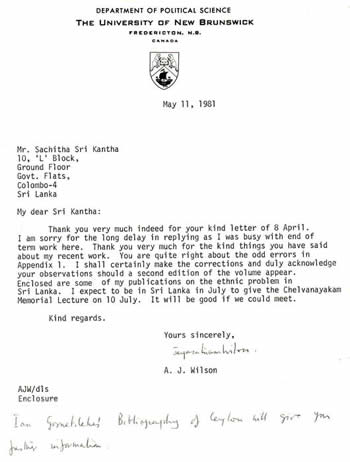

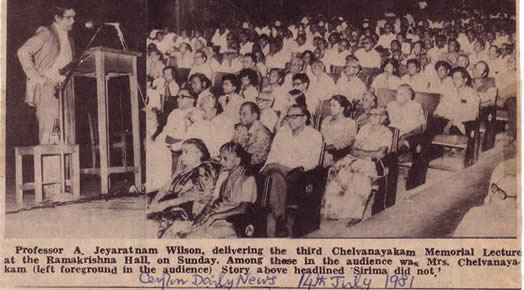

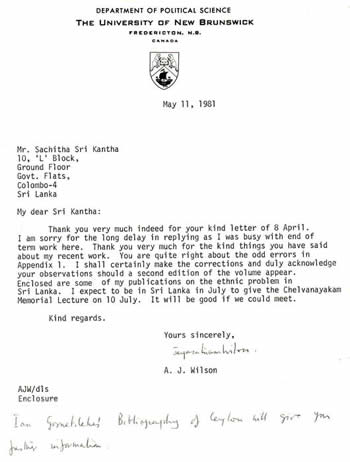

My acquaintance with Prof. Wilson began in 1981, few months before I left Sri Lanka. In April 1981, having heard that he will be visiting to deliver the Third Chelvanayakam memorial lecture, I wrote a letter to him. Sadly, I don’t have a copy of what I wrote to him then. But, I have preserved his reply. I present a scan of his letter dated May 11, 1981. In fact, I met him after his arrival in Colombo, and I also attended his memorial lecture. Few days later, this event was reported in the Colombo Daily News, with a montage photograph (showing Prof. Wilson and a segment of the audience). I had preserved this document as well, because I could be recognized in that photograph. Mrs. Emily Grace Chelvanayakam is seen in the first row (row A), second from right. I was seated in the third row (row C), sixth from right. Seated to my left in row C (fifth from right) was S. Sugumaran, the son of T. Sivasithamparam, ex-MP for Vavuniya.

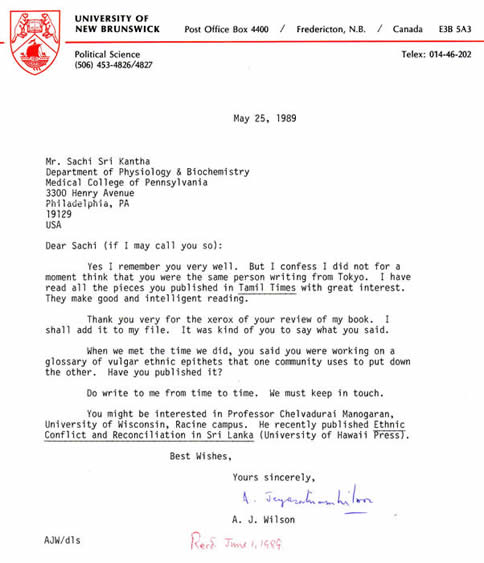

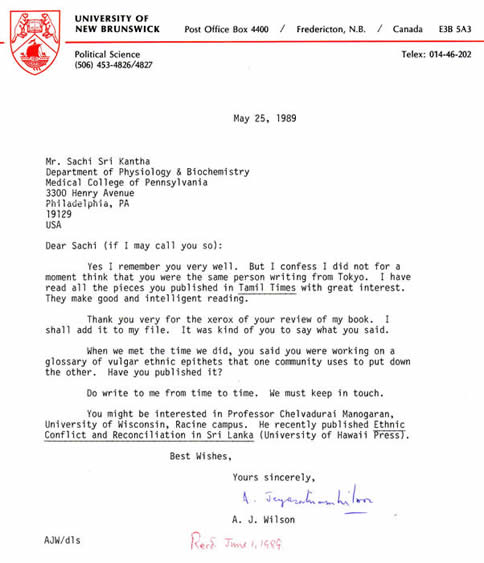

I don’t remember having any correspondence with Prof. Wilson for the next 8 years or so. But, in 1989, I sent a copy of my book review on ‘The Break-Up of Sri Lanka’ to him, and I received a courteous response in May 1989. A scan of this letter is provided nearby. By that time, I had completed my 3 year postdoctoral stint in Tokyo and moved to Philadelphia. While reading this letter from him, I was surprised that he had remembered what I mentioned when I met him in Colombo  in 1981. Having presented a preliminary paper on ethnophaulism at the Annual 1980 Meeting of the Sri Lankan Association for the Advancement of Science, I was keen on expanding my collection of vulgar ethnic epithets used by Sri Lankan ethnic groups. While living at the Arunachalam Hall (University of Peradeniya), I originated this study in collaboration with my then room-mate P. Vivekanandan for curiosity and to escape from boredom. But, having left the island, my priorities changed and I couldn’t keep in touch with the recent trends. As such, I had to answer Prof. Wilson that my collected data still remained unpublished. in 1981. Having presented a preliminary paper on ethnophaulism at the Annual 1980 Meeting of the Sri Lankan Association for the Advancement of Science, I was keen on expanding my collection of vulgar ethnic epithets used by Sri Lankan ethnic groups. While living at the Arunachalam Hall (University of Peradeniya), I originated this study in collaboration with my then room-mate P. Vivekanandan for curiosity and to escape from boredom. But, having left the island, my priorities changed and I couldn’t keep in touch with the recent trends. As such, I had to answer Prof. Wilson that my collected data still remained unpublished.

Since 1989, I have had the pleasure in corresponding with Prof. Wilson for the next 10 years. The materials we exchanged in the 1990s have to wait for another time.

**** ****

|

Home

Home Archives

Archives The fact that his death anniversary falls on May 31st is coincidental to the 1981 book burning event of Jaffna perpetrated by the Sinhalese goons and thugs, akin to the 1933 bibliocaust conducted by the Nazi sympathizers, should not be forgotten. Until now, I had written regularly on this 1981 book burning event for umpteen times to this site. The four part series, ‘Perversity of Pyromaniacs’, which I contributed in 2006, is probably the lengthiest to document this pathetic episode.

The fact that his death anniversary falls on May 31st is coincidental to the 1981 book burning event of Jaffna perpetrated by the Sinhalese goons and thugs, akin to the 1933 bibliocaust conducted by the Nazi sympathizers, should not be forgotten. Until now, I had written regularly on this 1981 book burning event for umpteen times to this site. The four part series, ‘Perversity of Pyromaniacs’, which I contributed in 2006, is probably the lengthiest to document this pathetic episode.

in 1981. Having presented a preliminary paper on ethnophaulism at the Annual 1980 Meeting of the Sri Lankan Association for the Advancement of Science, I was keen on expanding my collection of vulgar ethnic epithets used by Sri Lankan ethnic groups. While living at the Arunachalam Hall (University of Peradeniya), I originated this study in collaboration with my then room-mate P. Vivekanandan for curiosity and to escape from boredom. But, having left the island, my priorities changed and I couldn’t keep in touch with the recent trends. As such, I had to answer Prof. Wilson that my collected data still remained unpublished.

in 1981. Having presented a preliminary paper on ethnophaulism at the Annual 1980 Meeting of the Sri Lankan Association for the Advancement of Science, I was keen on expanding my collection of vulgar ethnic epithets used by Sri Lankan ethnic groups. While living at the Arunachalam Hall (University of Peradeniya), I originated this study in collaboration with my then room-mate P. Vivekanandan for curiosity and to escape from boredom. But, having left the island, my priorities changed and I couldn’t keep in touch with the recent trends. As such, I had to answer Prof. Wilson that my collected data still remained unpublished. ****

****