Ilankai Tamil Sangam30th Year on the Web Association of Tamils of Sri Lanka in the USA |

|||

Home Home Archives Archives |

Suu Kyi ReduxTwo reviews of her 1991 Bookby Sachi Sri Kantha, June 19, 2012

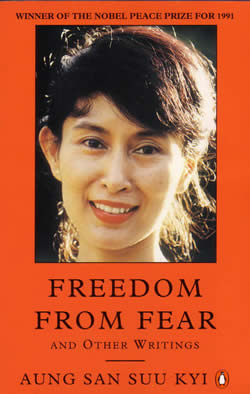

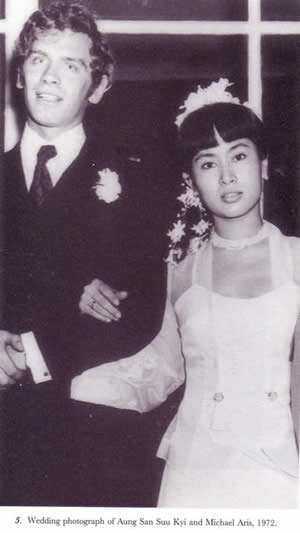

Freedom from Fear and Other Writings, by Aung San Suu Kyi, edited by Michael Aris, Viking and Penguin Books, London, 1991, 338 pp. paperback, US$12.00. My Review (June 15, 1992): Everyone has an opinion about the Nobel peace prize. In my view, this particular Nobel prize is a big equalizer. While other Nobel prizes are awarded to specialists who have excelled in a particular discipline (chemistry, physics, medicine, literature and economics), only the Nobel peace prize provides an opportunity for other folks to be nominated and recognized as having contributed something significant to the mankind. Therefore, the Nobel peace laureates belong to a medley of ‘heavy weights’ and mediocrities. They include social workers (Jane Addams and Mother Teresa), scientists (Linus Pauling), politicians (Oscar Arias Sanchez and Mikhail Gorbachev), one-time ‘terrorists’ (Menachem Begin), clerics (Desmond Tutu and Dalai Lama) and social activists (Martin Luther King). The last to win the Nobel peace prize, Suu Kyi, can be identified as a social activist, for the simple reason that she does not belong to any other professional category. The book, Freedom from Fear, is the compilation of her published writings, which has been edited by her British husband, Michael Aris. The Czechoslovakian leader Vaclev Havel, who nominated Suu Kyi for the Nobel peace prize, has written a short foreword to the book. What kind of a person is Suu Kyi? She was privileged to be born in 1945 as the daughter of the then Burma’s independence leader Aung San. In this sense, she shares a commonality with Indira Gandhi. However, in terms of age, family background and the personal tragedy they experienced in losing their fathers while being young, I believe that Suu Kyi shares much with Chandrika Bandaranaike. Even the political careers of S.W.R.D.Bandaranaike and Aung San show some surprising parallels.

The first was on her father, Aung San. The second was a general introduction on Myanmar, captioned ‘My Country and People’. The third one analyses the ‘intellectual life in Burma and India under colonialism’. The fourth essay relates to the literature and nationalism in Myanmar. The editor, Michael Aris, notes in his introduction that the majority of the assembled writings (a total of 17) are “a medley of later essays, speeches, letters and interviews resulting from her (Suu Kyi’s) involvement in the struggle for human rights and democracy in her country”. The author begins the titular essay, ‘Freedom from Fear’ (1991), by revising the well known dictum of Lord Acton on power. According to Suu Kyi, “It is not power that corrupts but fear. Fear of losing power corrupts those who wield it and fear of the scourge of power corrupts those who are subject to it.” Even in this essay, Suu Kyi relates to the deeds done by her father Aung San to his country, and compares him with Mahatma Gandhi. About Aung San, the author writes, “Always one to practice what he preached, Aung San himself constantly demonstrated courage – not just that physical sort but the kind that enabled him to speak the truth, to stand by his word, to accept criticism, to admit his faults, to correct his mistakes, to respect the opposition, to parley with the enemy and to let people be the judge of his worthiness as a leader.” This sounds similar to a toddler writing about her ‘lovely daddy’. It is understandable because Suu Kyi lost her father tragically, while she was just a two-year toddler. For an impartial analysis of what Aung San’s role in the independence movement of Burma, one needs to read the essay of the noted British anthropologist Edmund Leach, published in the journal Daedalus of winter 1973. In that analytical essay entitled, ‘Buddhism in the post-colonial political order in Burma and Ceylon’, Edmund Leach saw parallels between the dynamic careers and tragic deaths of S.W.R.D.Bandaranaike (1899-1959) and Aung San (1915-1947). His observations on these two ‘practical politicians’ are worth quoting in some detail. Leach noted, “…Contrary to legend, the Burma Independence Army, which Aung San then organized, was originally an insignificant group to which the Japanese offered little support. It is extremely doubtful whether this ‘army’ ever engaged in any form of combat…In the spring of 1945, Aung San, who had previously been denounced by the British authorities as a dangerous traitor, was suddenly recognized by Admiral Mountbatten as ‘the leader of anti-Japanese resistance in Burma’. Without this recognition Aung San would very likely have disappeared without a trace. The subsequent buildup of Aung San’s reputation as ‘Burma’s popular hero’ was very elaborately engineered…Aung San was certainly a devout patriot, but he was also an opportunist and a very practical politician…In any event, both Bandaranaike and Aung San seem to have perished because having ridden to power on the crest of a militant Buddhist nationalist wave, they would both have liked to reach some compromise agreement with the kind of Western ‘modern’ society which, in their hearts, they both really admired.” Suu Kyi, in the introduction of her 36-page essay on ‘My Father’ (1984) has noted, “My father died when I was too young to remember him. It was an attempt to discover the kind of man he had been that I began to read and collect material on his life. The following account is based on published materials…” However, what I found somewhat amusing is that, Suu Kyi has not referred to the above mentioned 1973 publication of Edmund Leach or even cited this particular research publication by the noted anthropologist. After all Edmund Leach is not an obscure scholar in Britain, and Daedalus is also not a mediocre journal. Has Suu Kyi been too sensitive to criticism about her father’s role in the colonial Burma? Edmund Leach compares U Saw who was implicated in the assassination of Aung San and hanged in May 1948 with Buddharakkhita Thero, the mastermind behind Bandaranaike’s murder. Edmund Leach concluded his comparison of Aung San and Bandaranaike as follows: “The point that I want to emphasize in the careers of Bandaranaike and Aung San and the careers of their murderers is not the cynicism involved in rapid changes of faith and political allegiance, or the corrupt immorality of the outstanding Ceylonese and Burmese politics make behavior such as Bandaranaike’s not merely appropriate but essential. In one way or another almost every successful operator in the field of politics in either Ceylon or Burma during recent decades has attempted (sometimes with considerable but shortlived success) to exploit Buddhist religious enthusiasms in the interest of party politics..”. Suu Kyi has not explored this territory in any of her writings in the book. And this is regrettable. In conclusion, despite some rave reviews about this book in the international press, I am of the opinion that this selection of the writings of Suu Kyi shows evidence as a hastily assembled production. We need to wait for a while to learn, how the incarceration currently being experienced by Suu Kyi, has influenced her political thoughts in a prolific way. One last comment about the incarceration of Suu Kyi. Though not to cast aspersions on her courage to withstand the rigours of prison life, one should note that at least she has the fortune to be alive and ‘treated with respect’ by the military authorities in Myanmar. Some other Gandhian activists in the past who underwent the same experience were not so lucky. Though deserving (by virtue of immersing themselves to the Gandhian way of struggle for a longer period of time than Suu Kyi), they wee not awarded the Nobel peace prize. For example, Mahatma Gandhi’s own wife, Kasturba Gandhi died in Yervada jail in Feb 1944 at the age of 75 years. And there is no doubt that Kasturba was the first woman to practice the Gandhian way of struggle. In 1983, Eelam Tamil Gandhian activist Rajasundaram and his colleagues were murdered in the Welikada jail. These facts prove how a Nobel peace prize can bestow credibility to the writings of an individual. Economist magazine Review (Jan. 18, 1992): In his foreword to this book, Vaclav Havel says Aung San Suu Kyi is an example of the power of the powerless. It is a nice phrase, but not wholly true. Miss Suu Kyi is not like the dissidents, Mr Havel among them, who persistently irritated the masters of the former Soviet empire but were not considered a real threat to them. She has also actual power, and is feared by the soldiers who run Myanmar, the name they have given to Burma. She is the legally elected ruler of the country. Her party won overwhelmingly in the 1990 general election that the soldiers, to their subsequent regret, allowed to take place and the results of which they have refused to honour. In December the junta claimed that Miss Suu Kyi had been expelled from her party. Few Burmese accept this, and assume it is another sign of the junta’s nervousness. Miss Suu Kyi’s presence in Myanmar is a nagging reminder that democracy’s time will come again, even in a country where it has been suppressed since 1962. Some in the regime, for whom the gun is the solution for difficult problems, would like to kill her. But Miss Suu Kyi is a soldier’s daughter, which gives her a special status. And the protection the outside world seeks to provide her with, such as the award of the Nobel peace prize, is not without value. So the regime pleads with her to leave the country. Surely you would like to see your husband again, at Harvard? Miss Suu Kyi declines, even though she is confined to her house. She does not want to become just another political exile. That would be very ordinary, and she is far from that. One of the most interesting essays in her book is an honest account of her father, Aung San. When the second world war broke out in Europe, Aung San, a politician with a following among students, was wooed by the Japanese. When Japan invaded Burma in 1941, he was a general in an ‘independence army’ that marched ‘with great pride and joy’ alongside the Japanese troops. In 1943 he was decorated by the Japanese emperor in Tokyo. In 1945, when it was clear that the Japanese were going to lose, he sided with the British. In 1947, when Burma was close to independence and Aung San was on its Executive Council, he was assassinated. Not perhaps a conventional hero in western eyes. Miss Suu Kyi, too, is more subtle than she seems. A good reason for reading this book is to try to understand the woman who is likely, eventually, to run this beautiful, benighted country.” End Note Whereas the reviewer for the Economist provided a rather shallow account about the contents of the book, I did comment about the ‘meaty pieces’. While the Economist reviewer presented Suu Kyi’s account of her father Aung San as an “honest account”, I did note what Suu Kyi omitted, by citing British anthropologist Edmund Leach’s study about the not-so pleasing account of Aung San’s stature. When the 1991 Nobel Peace Prize award was announced to Suu Kyi, I was disappointed that Suu Kyi had beaten Nelson Mandela to the Nobel peace prize. I felt why Suu Kyi (who then had only two years of peace activism) was the preferred choice over Mandela (who spent 27 years in prison). Even the hasty release and rave reviews, including that of the Economist, in the mainstream press for this ‘book’ before her Nobel award was meant for her Western publishers and promoters to mint some money. Thus, I wrote a rather not-so appreciative review. Mandela was awarded the well-deserved Nobel peace prize in 1993. But make a note. Suu Kyi’s 1991 award was a solitary prize; but, the 1993 award for Mandela was a shared prize. How does one explain this? Now, 20 years later, after studying the trend of Nobel peace prizes I come to infer that the Nobel peace prizes, since 1947, can be simply divided into two groups; (1) pro-CIA group, and (2) anti-CIA group. Occasionally, the Peace prize selection committee split the prize between the pro-CIA and anti-CIA groups. Mandela’s 1993 prize belonged to this category; Mandela (anti-CIA) and de Klerk (pro-CIA). Suu Kyi’s 1991 prize belonged to the pro-CIA group. Rare were the occasions, when the peace prize was awarded to impartial nominees like that of Albert Schweitzer (1954) and Mother Teresa (1979). Why I chose CIA as the yard stick? Whether one likes it or not, CIA (since it became operational on Sept.17, 1947) has come to play a lead role in contributing to global peace by its deceptive activities. And the Nobel Peace Prize selection committees are directly or indirectly influenced by the CIA activities. This will be an interesting and challenging topic to cover in a future commentary. *****

|

||

|

|||

Now that Aung San Suu Kyi, the pro-democracy leader of Myanmar, had visited Oslo, and delivered the Nobel Peace Prize lecture on June 16th, it may be of some relevance to check what I wrote in reviewing her book, Freedom from Fear and Other Writings (1991), published in anticipation of the Nobel Peace Prize. Suu Kyi was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1991. My 1,362 word review of this book appeared in the print edition of Tamil Nation (London), in June 15, 1992. I have not deleted a single word from the original. For comparison, I also provide the 445-word review of the same book that appeared in the Economist magazine (January 18, 1992). As is typical to the convention adopted by the Economist, the reviewer was not identified by name. I comment on the difference between the two reviews, in the End note.

Now that Aung San Suu Kyi, the pro-democracy leader of Myanmar, had visited Oslo, and delivered the Nobel Peace Prize lecture on June 16th, it may be of some relevance to check what I wrote in reviewing her book, Freedom from Fear and Other Writings (1991), published in anticipation of the Nobel Peace Prize. Suu Kyi was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1991. My 1,362 word review of this book appeared in the print edition of Tamil Nation (London), in June 15, 1992. I have not deleted a single word from the original. For comparison, I also provide the 445-word review of the same book that appeared in the Economist magazine (January 18, 1992). As is typical to the convention adopted by the Economist, the reviewer was not identified by name. I comment on the difference between the two reviews, in the End note. Twenty five documents constitute the body of this book. Of these 25, four were authored by colleagues who have known Suu Kyi either personally or professionally. Among the remaining 21 documents, four pieces constitute the ‘meaty material’. These were written while the author was residing in Oxford, Kyoto and Simla, and published between 1984 and 1990. The themes of these four essays relate to Myanmar.

Twenty five documents constitute the body of this book. Of these 25, four were authored by colleagues who have known Suu Kyi either personally or professionally. Among the remaining 21 documents, four pieces constitute the ‘meaty material’. These were written while the author was residing in Oxford, Kyoto and Simla, and published between 1984 and 1990. The themes of these four essays relate to Myanmar.