Ilankai Tamil Sangam30th Year on the Web Association of Tamils of Sri Lanka in the USA |

|||

Home Home Archives Archives |

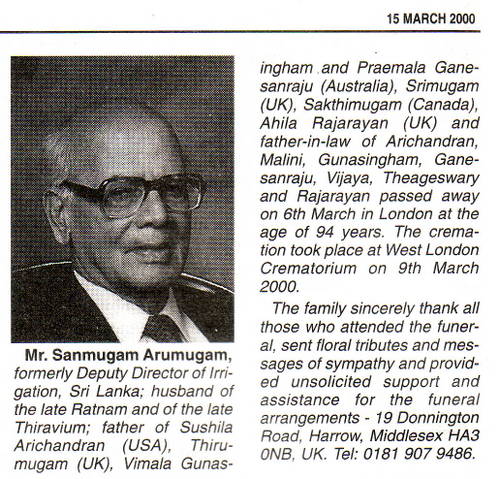

Sanmugam Arumugam (1905-2000)Eminent irrigation engineer and encyclopedic scholar, Part 1by Sachi Sri Kantha, August 6, 2012

August 31st marks the 107th birth anniversary of Sanmugam Arumugam, one of the foremost irrigation engineers of the 20th century Ceylon and an encyclopedic scholar. I offer this two part essay on the versatile talent of this engineer who’s name is not well known beyond the circles in which he interacted. The Tamil Times (London) of May 2000 carried an unsigned eulogy to his life in two pages. In this part 1, I provide the enlightening eulogy of almost 2,000 words in its entirety at the end.. I hope that the author of this eulogy (if he or she is still living) comes forward to identify himself (or herself) to me. This is for the simple reason that I wish to assign proper credit to the author. From the details provided in it, one can be certain that the eulogist had engineering knowledge and was a close pal of Arumugam. In part 2, I offer my review of his encyclopedic work Dictionary of Biography of Ceylon Tamils (1997), albeit 15 years late.

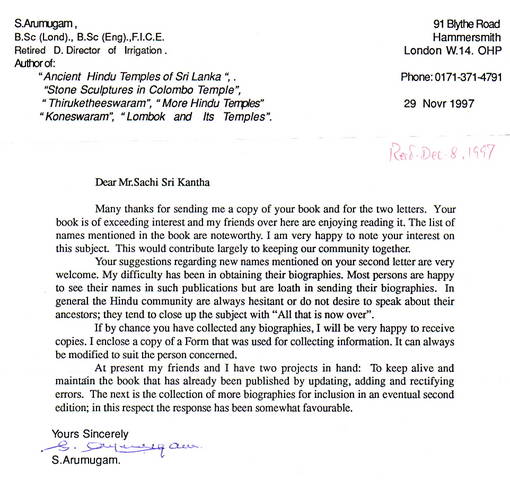

In fact, one of Arumugam’s sons Sakthimugam was one of my batchmates at the University of Colombo in early 1970s. He was known to us with the prefix of his first name, Sakthi Arumugam. Since he was in physical sciences section, while I was in biological sciences section, we hardly had much time to interact. As such, I was unaware of the fact that Sakthi’s father was an elite engineer. However, before I left the island March 21, 1981 (Saturday), I went and met him once at his residence, at the insistence of my father. My diary entry on this day says this: “Aiyah [i.e., father] introduced me to one Kasinathan and he took me to Polhengoda, to meet the engineer Arumugam. To my surprise, after I reached their home only I came to know that it was only Sakthi’s – my batchmate’s – father! Three of us had a long chat on the religious temples, and Arumugam showed me his latest manuscript on the Sivan Temples of Medieval Period. It was around 11:30 only, I left their place.” Later in 1990s, through my mutual Tamil circle members living in London or nearby (C.J.T.Thamotheram, S.Sivanayagam and N.Satyendra), I was made aware of Arumugam’s, one of its kind compilation ‘Dictionary of Biography of the Tamils of Ceylon’ (1997). Then, I wrote two letters to him and received his response in December 1997. He was then 92 years old. I was delighted. How often one receives a complimentary letter from a nonagenarian author belonging to one’s ethnic group? Not many Tamil males live up to 90 years. Not all who live up to 90 years had an enriched life to serve the community. As such, Arumugam was an exception to me. In his letter, he had specifically criticized the lackadaisical mentality of the Tamil tribe. I provide a scan of his letter nearby. He had written,

List of '100 Influential Sri Lankan Tamils of the 20th Century When I check my 1995 list of influential Tamil personalities of Sri Lanka, I note that I have strictly followed the definition provided by the Life magazine in 1990. I have included in my list, some personalities (such as Prof. K. Sivathamby, Prof. K. Kailasapathy, Neelan Tiruchelvam, Rajani Thiranagama) whom I have criticized in this website subsequently. But, I did grant them, the ‘influential status’, because their thoughts and deeds influenced either positively or Of the two Muslims in my list, Prof. M.U. Sultan Bawa was an influential chemist who shaped the careers of many young Tamils. So, I felt that he deserved his place. Jabir A. Cader, was an influential Muslim businessman and movie mogul, who also shaped the careers of a few Tamils in Sinhala movie industry. Journalist and actor Richard de Zoysa’s mother Dr. Manorani Saravanamuthu was a Tamil. Despite his blurred ethnic identity and political activism promoting JVP ‘revolution’, I felt that his abduction and death in February 1990 from Sri Lankan state’s vigilantes and death squads was a revelation that democracy had failed in Sri Lanka. Cricketer M. Muralitharan’s name deserves inclusion now. But, in 1995, he was yet to establish his reputation at the age of 23! After I became a regular contributor to this website, based on my personal knowledge, personal interactions and my archival collections, whenever feasible I have made a valiant attempt to profile some vital facets of the careers of 22 who have been included in my list, in this website. These 22 are as follows: Legislators: S.J.V. Chelvanayakam, G.G. Ponnambalam, S. Thondaman, M.G. Ramachandran, M. Sivasithamparam, A. Amirthalingam. Social Activists: V. Prabhakaran. Administrators: K. Alvapillai Natural Scientists: Prof. C.J. Eliezer, Prof. C. Sivagnanasundaram (Nandhi) Social Scientists: James T. Rutnam, Prof. A.Jeyaratnam Wilson, Prof. K. Kailasapathy, Prof. K. Sivathamby. Literati: Prof. S. Vithiananthan. Educators: Fr. S.Thaninayagam, Pundit K.P. Ratnam, Dr. Rajani Thiranagama. Commentators and Journalists: S.P. Amarasingam, S. Sivagnanasundaram (cartoonist), S. Sivanayagam, Dr. Neelan Tiruchelvam. My objective of producing the profiles of remaining 78 still appears too distant for me to reach. There isn’t another engineer Arumugam to guide me now. I do share his sentiments expressed in his 1997 letter in the difficulty of collecting vital facts and data in collecting information from the Tamil Hindu-Christian community in Sri Lanka. Still we hardly know much about folks like poet and legislator C.V. Velupillai, journalist S.J.K. Crowther, movie mogul K. Gunaratnam, electrochemist M.A.V. Devanathan. Unsigned eulogy to Arumugam [source: Tamil Times, London, May 15, 2000, pp. 30-31] “Sanmugam Arumugam was born in Nallur, Jaffna, Sri Lanka on 31 August 1905, the only son of Vairavanather Sanmugam. Whnen the time came to enter primary school, Arumugam was admitted not to Jaffna Hindu College, where a scholarship awaited him as the son of a former Director of the college, but to St. Johns College, purely because travel to the school from his home in Nallur was easier. In 1921 he passed the Cambridge Junior examination with distinctions and was ranked first in the school. His mother then decided that his further education should be in a Colombo school. When the principal of St. Johns, Revd. H.Peto heard about this, he visited Kanagammah in her home and tried to persuade her to let Arumugam continue at St Johns. The compromise that was reached was that if Arumugam was to study in Colombo, it would not be at Royal College but at St. Thomas College which was in the same mission as St.Johns. In 1922 Arumugam set forth from Jaffna in the relatively new train service to Colombo and joined St. Thomas College which was then headed by Warden Stone (known by contemporaries as the Stone Age of the College!). Arumugam passed the Cambridge Senior examination in 1923 with distinctions and based on his performance in the examination he was exempted from the London Matriculation examination. He entered the Ceylon University College in 1923 and obtained a Science degree in 1927, coming second in order of merit. At that time there were two government scholarships awarded annually for further study in the UK, and he assumed that normal selection policy would be followed and he started making arrangements to proceed to UK to study for an engineering degree at Kings College, University of London. When the scholarship results were announced, he found to his surprise that the first and sixth in order of merit were awarded scholarships! Nevertheless he decided to proceed to the UK to study engineering at his own expense. He graduated with a civil engineering degree from Kings College in 1930 and then proceeded to work in Haweswater in the Lake district on construction work for a reservoir for the Manchester city water supply. He lived in the little village of Butterwick where he was an object of curiosity because none of the local inhabitants had previously seen a coloured person. He returned to Ceylon in 1932 and joined the Irrigation department, where he was the third Ceylonese engineer to be recruited. He rose to the department’s directorate level by 1950 and continued to work in the Irrigation department until his retirement at the age of 60 years in 1965. During his 32 years in the Irrigation department, he worked in all parts of the country, including the malarial dry zone. Three schemes in which he was fully involved deserve to be mentioned. The first was in 1948 when he was the Divisional Irrigation engineer, Northern division, based in Vavuniya. He used some surplus funds available for minor village irrigation works to build a dam at Palavi, thus providing a tank for the Tiruketheeswaram Temple. This enabled the ‘Palavi Theertham’ to be held at Thiruketheeswaram in 1949 after a lapse of over 300 years. He was fully involved in the restoration of the temple and he was Chairman of the Construction Committee. The second scheme was the Urellu Well windmill pumping scheme in Jaffna. At Puthur there is a well known as Nilavarai which is reputed to be ‘bottomless’ and all previous attempts going back over 100 years at pumping out the water with powerful pumps made hardly any impression on the water level. This engaged the natural curiosity of Arumugam, and he was determined to get at the bottom of it! First of all soundings were made and it was established that the well was not bottomless but was about 164 feet deep ending up in huge underground cavern. Next, samples of water were taken at different depths and it was found that there was a light fresh water lens of water about 50 feet deep riding on top of heavier sea water below. When pumping was commenced with powerful diesel engine driven pumps, it was found that the fresh water lens became narrower as the pumping rate was faster than the rate of fresh water recuperation. However the well level was being maintained because the salt water percolated rapidly into the well from the sea several miles away through the fissures in the Jaffna limestone strata. Mystery solved! The hydrological data obtained from these pumping trials was then used at the Urellu Pokkunai well, which has similar recharge characteristics, to install a Hercules windmill pump in 1952 to provide irrigation water for the surrounding fields at virtually zero running cost. This was the first windmill installation in the Jaffna peninsula. The third scheme was his proposal for a ‘river for Jaffna’ which is yet to be fully implemented. Every time during the North East monsoon when he crossed the Elephant Pass bridge, he would stop in the middle of the causeway and look at the large volumes of fresh water flowing from the Elephant Pass lagoon in the east to the sea (Jaffna lagoon) in the west and think ‘Surely there must be a way of utilizing this fresh water for the benefit of the Jaffna peninsula’. The scheme that he proposed (called the ‘Arumugam Plan’ by others) was briefly as follows. The Kanagarayan Aru which flows from the Vanni mainland northwards, discharges monsoon floodwaters into the Elephant Pass lagoon, and this water flows under the Elephant Pass bridge and westwards into the sea. A dam and spillway at the Elephant Pass bridge and a 4,700 foot long embankment and spillway at the eastern seaside end of the Elephant Pass lagoon at Chundikulam would trap this fresh water in the 11,400 acre Elephant Pass lagoon. A two and a half mile long link channel at Mulliyan is then constructed from the northern end of Elephant Pass lagoon to lead this fresh water into the Vadamarachchi lagoon at its southern tip. The Vadamarachchi lagoon is a large inland lake which stretches from Mullinan in the south, through Chempianpathu, Eluthumodduval, Varani and Karaveddi and then to the sea at Thondaimannar. It also branches off at Sarasalai and extends towards Jaffna town connecting to the sea also at Ariyalai near Chemmani. It has an average width of about a mile and more or less extends through the heart of Jaffna peninsula. The barrage at Thondaimannar prevents salt water intrusion at that end, and a spillway and gates at Chemmani will prevent salt water intrusion there, and you then have a river of fresh water flowing through the heart of the Jaffna peninsula. The barrage at Thondaimannar was refurbished and the spillway at Chemmani constructed in the 1950s and this brought immediate improvements to the well water quality in many parts of Jaffna, which the older generation will no doubt recall. In the 1960s work commenced on the Chundikulam bund, the spillway at Elephant Pass bridge and the Mulliyan channel. The Chundikulam bund was constructed but subsequently breached. The spillway at Elephant Pass bridge was completed, but the Mulliyan channel which was to lead the fresh water from Elephant Pass lagoon to the Vadamarachchi lagoon was never completed. It was Arumugam’s hope that one day this scheme will be completed because the benefits that it will bring to the Jaffna peninsula are immeasurable. After his retirement from the Irrigation department, he continued to work in the Water Resources Board as chief engineer and director until he finally retired at the age of 72 years. He was the President of the Institution of Engineers, Ceylon, and President of the Engineering section of the Ceylon Association for the Advancement of Science. He read numerous technical papers before these two organisations. He alerted the general public to the dangers of over-pumping water from wells in Jaffna as this would lead to increasing salinity. His published technical books include, Development of Village Irrigation Works (1957), Maintenance of Major Irrigation Works, Ground Water in the Jaffna Peninsula, and a monumental volume entitled Development of Water Resources of Ceylon (1969), which was a detailed study of every river basis in Ceylon, and is a standard reference work on the subject. His last two papers on technical matters will in fact be published posthumously and will appear shortly in a publication to be issued by the Irrigation department to commemorate the 100th anniversary of the department which was established in 1900. D.L.O. Mendis, a former president of the Institution of Engineers, Sri Lanka, and adviser to the Ministry of Planning and Economic Affairs is a self-confessed academic disciple of Arumugam, and wrote in one of his books that, “This author has repeatedly paid tribute to S.Arumugam, now a nonagenarian living in London, as the foremost engineer in his time who recognized the true significance and value of the ancient small tank systems. He was thus implicitly opposed to the conventional wisdom of the hydraulic engineers who dominated the scene in the Irrigation department and led the Irrigation ministry to follow them. This conventional wisdom maintained that the small tanks were ‘inefficient’ and had to be replaced by large reservoirs and channel systems. Sadly the hydraulic engineers had their way.” In fact it was Arumugam’s interest in small tanks that led to his most productive period in writing about Tamil culture and Hindu temples, after his retirement. He had noted when investigating abandoned Northern and Eastern province village tanks for possible restoration that each tank invariably had a temple beside it, usually in ruins. He started taking photographs of these temples and collecting information about them, and this led to the publication of his book Some Ancient Hindu Temples of Sri Lanka (1980). This was followed by Thiruketheeswaram (1981). He was a founder member of the Thiruketheeswaram Restoration Society and a Vice President of the Society. Stone Sculptures in Colombo Hindu Temple (1990), Thiru Koneswaram (1990), Lombok and its Temples: an exploratory study of the ancient Hindu monuments of Java, Bali and Lombok (1991) and More Hindu Temples of Sri Lanka, are amongst his other publications. In 1997, he completed and published a Dictionary of Biography of Ceylon Tamils. This publication contains potted biographies of more than 750 Ceylon Tamils over a period ranging from the kings of Jaffna to the present day. This book publicized some of the achievements of Ceylon Tamils, for example the fact that the first Asian lawyer to be called to the London Bar was a Ceylon Tamil, Muttu Coomaraswamy in 1862. During the past two years he has been a regular visitor to the London Tamil Elders Centre in Wembley, where he delivered over 50 educational and informative lectures on a wide variety of topics on Hindu culture and Tamil civilization. In 1999, Shruthi Laya Shangham, a London-based cultural organization, approached him for information about the five ancient Shiva (Pancha Ishwaram) temples in Sri Lanka: Koneswaram, Thiruketheeswaram, Thondeswaram, Naguleswaram and Muneswaram. Arumugam duly obliged with the background information on these pre-Christian era temples of antiquity, and lyrics and music were added by the foremost violinist from Tamil Nadu, Lalgudi G. Jayaraman. Choreography and dancers were from Kalaschestra in Chennai and the performance was held at Logan Hall, University of London on 16th October 1999. At the end of the performance which was rapturously received by the audience, Lalgudi came down from the stage to the audience and draped a ‘ponnadai’ on Arumugam as recognition of his lifelong work. He was by nature a quite, humble man who avoided the limelight, but he was a life long workaholic. He mastered the computer in his eighties and until a few weeks before he passed away he would spend several hours a day on the word processor, interspersed with a long daily walk in the park, whatever the weather. He passed away on 6th March 2000, after a brief illness.” *****

|

||

|

|||

Arumugam’s given name means six faces (Aru=six, Mugam=face), which refers to one of Lord Muruga’s facial attribute. It is a very popular name for Hindu men. Very rarely, one’s name befits the personality. But for Arumugam, his name and personality fitted handsomely. He seems to have been blessed with six faces, observing the minutiae of his surroundings splendidly; while engaged in engineering profession, he also had a penetrating eye to the cultural facets of the area and the ethnological history. Then, he did write up his observations.

Arumugam’s given name means six faces (Aru=six, Mugam=face), which refers to one of Lord Muruga’s facial attribute. It is a very popular name for Hindu men. Very rarely, one’s name befits the personality. But for Arumugam, his name and personality fitted handsomely. He seems to have been blessed with six faces, observing the minutiae of his surroundings splendidly; while engaged in engineering profession, he also had a penetrating eye to the cultural facets of the area and the ethnological history. Then, he did write up his observations. The book he refers in his letter was my 1995 publication, MGR Movies Revisited and Other Essays (114 pages). Among its 20 chapters, I have included one short chapter, with the caption,

The book he refers in his letter was my 1995 publication, MGR Movies Revisited and Other Essays (114 pages). Among its 20 chapters, I have included one short chapter, with the caption,  negatively, the history of Tamils in the island. When I solicited comments from few of my colleagues (especially N. Satyendra and Prof. S.Sivasegaram) about this list, I remember Satyendra stating that ‘the list is controversial’. Prof. Sivasegaram mentioning, (1) A few you have included (such as Richard de Zoysa, and three Muslims ) may not consider themselves as Tamils. (2) You should add Muttiah Muralitharan (cricketer) to the list. I do accept their constructive criticism in the spirit it was made.

negatively, the history of Tamils in the island. When I solicited comments from few of my colleagues (especially N. Satyendra and Prof. S.Sivasegaram) about this list, I remember Satyendra stating that ‘the list is controversial’. Prof. Sivasegaram mentioning, (1) A few you have included (such as Richard de Zoysa, and three Muslims ) may not consider themselves as Tamils. (2) You should add Muttiah Muralitharan (cricketer) to the list. I do accept their constructive criticism in the spirit it was made.