Ilankai Tamil Sangam30th Year on the Web Association of Tamils of Sri Lanka in the USA |

||||

Home Home Archives Archives |

Oil and Violence in Sudan Drilling,Poverty and Death in Upper Nile Stateby Egbert Wesselink and Evelien Weller, Multinational Monitor, May/June 2006

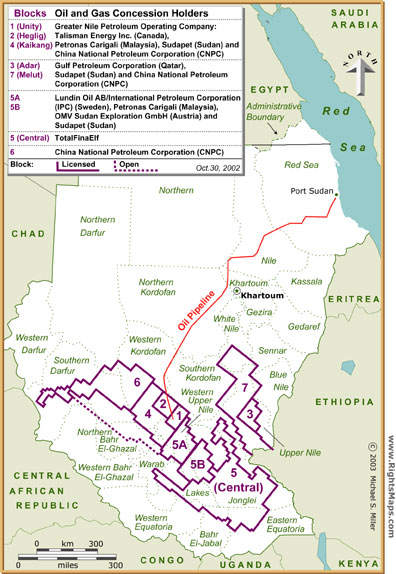

The discovery of oil in a developing country can be a blessing or a curse. In Sudan’s case, oil exploration and development has helped fuel vicious warfare. The 2005 Sudan Comprehensive Peace Agreement (CPA), which brokered an end to fighting between the Sudanese government and the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement (SPLM), offers a framework to depart from that brutal legacy, but so far its promise has not been realized. Sudan’s largest oil field is located in Western Upper Nile, southeast of the capital, Khartoum. Most of the international focus on the intersection of oil and violence in Sudan has been directed towards this area. But oil development is now proceeding rapidly in another oil field east of there, in the Melut Basin in Upper Nile State, with a disturbingly similar story line. Areas that the government has designated concession blocs 3 and 7 lie in this region. They are located in Melut and Maban Counties, in Renk District. Oil development rights for these concession blocs are currently held by the Petrodar Operating Company Ltd. (PDOC) under an Exploration and Production Sharing Agreement with the Sudanese government. The Petrodar Operating Company is jointly owned by the China National Petroleum Company (CNPC, 41 percent), Petroliam Nasional Berhad (Petronas of Malaysia, 40 percent), Sudan Petroleum Company (Sudapet, 8 percent), China Petroleum & Chemical Corporation (Sinopec, 6 percent), and Al Thani Corporation (United Arab Emirates, 5 percent). Petrodar has served as a loyal partner of the government of Sudan. It has never raised its voice against the government’s use of violence to clear the way for oil development; and the government’s war strategy has been guided by a desire to pave the way for oil extraction and the funds it promises. Petrodar has evidenced virtually no concern for the people or environment of Renk District. Displaced residents of Upper Nile State had reason to hope for dramatic change after the signing of the Comprehensive Peace Agreement in January 2005 between the Government of Sudan and the SPLM. The CPA contains a range of principles and measures that offer a coherent framework for reforming Sudan’s oil sector and popular trust-building, but the relevant provisions remain a dead letter. Petrodar has not reversed its pattern of environmental and social neglect; and there is no process in place to change its conduct, nor to assure fair compensation and redress for the people who have suffered. In the nearly 50 years since it gained independence, Sudan has known mostly military rule. Most of those years have been marked by a bloody civil war, stretching from 1955 to 1972 and again from 1983 to 2005, between the central government and the vast majority of the people in the South. The Melut Basin is remote and under-reported. It lies on the northernmost edge of the Southern side of the former North-South front line, in a region that has not had a single permanent international presence since the Sudan’s civil war began. The inhabitants are predominantly Dinka and Maban agro-pastoralists, and non-Muslim. They mostly live by herding, cultivation and fishing. During the wet season, they stay in permanent settlements on slightly higher ground, for the most part small sandy ridges, surrounded by the black clay soil that floods and is not fit for settlement. A village in this area would typically count between 200 and 500 inhabitants. The Chevron Find Oil exploration in Sudan started in 1959, when Italy’s Agip was granted concessions in the Red Sea area. It was not until 1978, however, that Chevron, operator of a consortium in which Shell took a 25 percent interest, made the first important strike — not in northern Sudan, but in the Muglad Basin stretching deep into Western Upper Nile. In 1981, Chevron made a second, smaller find at Adar Yale in the Melut Basin in Northern Upper Nile, a predominantly Dinka area east of the White Nile. A year later, Chevron made a third, much larger discovery at Heglig, 70 kilometers north of the Unity field in Western Upper Nile. For the next 20 years, the fields in Western Upper Nile were to be the main focus of interest for the Sudanese oil industry. In late 1983 and early 1984, less than a year after the outbreak of civil war between the Northern-dominated government and the ethnically diverse South, the Sudan People’s Liberation Army (SPLA, affiliated with the SPLM) kidnapped and subsequently released a number of Chevron employees. Shortly afterwards, the SPLA attacked Chevron’s operational base. Chevron suspended its operations and virtually all its staff was evacuated by air within 18 hours of the attack. In 1989, a coup d’état brought the National Islamic Front (NIF) to power and the civil war intensified. Chevron left Sudan in 1990, under pressure from the Sudanese government to operate or quit. Chevron’s huge concession was then divided into smaller units. For several years, the Sudanese government struggled to get capable companies interested. The government awarded blocs 3 and 7 to Gulf Petroleum Corporation-Sudan (GPC), a private consortium in which Qatar’s Gulf Petroleum Corporation had a 60 percent stake, Sudapet held 20 percent and Concorp International, a private company owned by the NIF financier Mohamed Abdullah Jar al-Nabi, 20 percent. GPC only managed small-scale production, but serious government violence accompanied the consortium’s operations. Government forces attacked and burned villages in order to clear the way for GPC to cut a road through inhabited, cultivated areas. “After the militias attacked and killed,” says the paramount chief of the Dinka Nyiel (a Dinka sub-group), Deng Nuor, “the army came with tanks and burned villages. They chased us away from our areas — and then they built roads and brought electricity! Now all our areas are covered in wells.” Deng Nuor said the first large villages destroyed near the Khor Adar River (the Khor Adar is a seasonal tributary to the White Nile) were villages close to the place where the main oil road south from Paloich crosses the Khor Adar. He estimates that almost half the population perished in the attacks. “Approximately 1,000 people lived in [one village], Agor Ti,” he says. “About 400 died, most of them by shooting.” In November 2000, nine months after the Harker report, a high-profile Canadian government-commissioned investigation into the link between oil development and human rights violations, confirmed that “oil is exacerbating conflict in Sudan,” the Sudanese government awarded blocs 3 and 7 to the Petrodar Operating Company Ltd (PDOC). Changes on the ground were immediate and impressive. A comprehensive oil development infrastructure began to be built, including 31,000 barrels-a-day field production facilities at the Adar Yale fields, a full-size airfield, and hundreds of kilometers of all-weather roads and feeder-pipes. Kotolok, just west of Paloich, became the center of operations and the hub for the 1,392-kilometer pipeline to Port Sudan that was inaugurated in April 2006. Blocs 3 and 7 are expected to produce 300,000 barrels-a-day in late 2006. With the current oil prices around $70 per barrel, by the end of this year, the Melut Basin could generate well over $10 million per day for the state, in addition to Petrodar’s profits. Destruction and Displacement Northern Upper Nile has suffered the same pattern of oil-related death, destruction and displacement as Western Upper Nile, though on a smaller scale. Many villages north and east of the Khor Adar River — formerly a frontier between the government of Sudan and the SPLM — have been emptied. Destruction in blocs 3 and 7 was carried out primarily by the regular Sudanese army and government-supported Dinka militias, at several occasions backed by helicopter gunships or even high-altitude bomber aircraft, despite the fact that the SPLA presented no direct threat to oil exploitation. Many settlements were burned. In an appeal to the international community in 2002, the Episcopal Bishop of Renk, Daniel Deng Bul, counted 21 torched villages in the vicinity of Melut alone, the result of a policy of “clearing the area of the local population, whom they expect to have relations with the SPLA.” The wave of destruction peaked in 1999-2002, preceding and coinciding with the development of the oil fields. Local church leaders claim government-backed militias destroyed 48 villages in 2000-2001 and several villages were destroyed in the Guelguk area. Lela Ajout Along, a Member of Parliament for Melut and Renk, has recently carried out a survey which lists a total of 168 emptied villages. “The army declared a rule,” says Bishop Daniel Deng Bul. “If a person is found after this in the area where the Chinese are working, [it] can cost his or her life. Most young people have left Melut towards the North, afraid of being captured, arrested or killed by the army.” Abuses continued, albeit on a lesser scale, in the ensuing years. In June 2004, the government increased its military forces in northern Upper Nile and moved in a battalion of 700 men. The reinforcement, which violated a Memorandum of Understanding requiring the parties to cease fire and “retain current military positions,” coincided with the transport of sections for the pipeline from Kotolok to Port Sudan. “When the pipeline was being built,” says Commissioner Elijah Bioch, SPLM Commissioner of Melut, “people started to disappear on the road. If you travelled in a bus or lorry you would be safe. If you were footing, you would be killed.” North of Paloich, the pipeline passes close to the garrison town of Renk. A number of villagers complained about the damage done to their farming lands. Petrodar responded by calling in the army. A similar problem arose in Kubri village in November 2004. People in Kubri complained to the Chinese workers that the pipeline prevented them from cultivating their land. The Chinese told the army, which arrested many people. They were released after the intervention of the civil authorities, but the pipeline is still there. Oil exploitation has coincided with a decline in the rural population in parts of Melut and Maban Counties. This is mostly due to forced displacement of the Dinka and Maban populations, and partially to the effects of cheap and environmentally harmful engineering. The total number of people forcibly displaced is at least 15,000; the true number could easily be double that figure. The majority of the displaced from the oil fields have found refuge in the regional centers Renk, Melut, Paloich and Maban, and in the SPLM-controlled area along the White Nile, south of the Khor Adar. They are ruined and have inadequate access to all basic human needs from shelter and food, to education and health services. To return to their places of origin, they will need security guarantees, tools and equipment, food, livestock and seeds. Since the signing of the Sudan Comprehensive Peace Agreement, some people have begun to return to their villages, only to find that some of them no longer exist. Most of Upper Nile consists of black cotton soil that is swampy in the wet season and forms deep cracks in the dry season. It is extremely difficult to build on. It is not fit for living. However, there are numerous sandy “ridges” of slightly higher ground, and it is on these that the people build their villages. To economize, Petrodar has unearthed neighboring sandy ridges for road construction. Alongside oil roads, there are huge holes in the ground where villages used to stand. The companies have appropriated some sandy ridges. For example, where Kotolok, formerly an important village, was located, now sits the main oil base, about 15 kilometers from Paloich on the road to Melut. There is also widespread resentment among displaced villagers because the graves of the ancestors, who are buried in the villages, have been desecrated. Their remains are now scattered in the oil roads. Environment Under Siege Crop patterns in Melut County have changed dramatically from November 1999, mostly due to displacement of villagers and partly to hydrological alterations as a result of cheap and inconsiderate engineering. The hundreds of kilometers of all-weather roads constructed by Petrodar have hurt agricultural production and partially dammed seasonal tributaries to the Nile, including the Khor Adar. Satellite imagery confirm the statements from local residents that the roads are acting as dams and preventing the natural flow of water. This leads to flooding in some areas and drought in others. In 2005, even parts of Renk town were flooded. People have cut the road open themselves to allow the water to drain away, according to ECS Bishop Daniel Deng. In March 2006, the remains of houses destroyed in the 2005 floods in the northern part of Renk were still visible. From Geger to Renk, a distance of 40 kilometers, there are reports that agriculture was seriously affected by floods. Lela Ajout Along, the Member of Parliament for the Renk and Melut area, made a fact-finding trip in January 2006. She reported food shortages in the area and referred the matter to the World Food Program for investigation. She discovered that vegetable gardens around Abu Khadra had failed and that in some areas cows have died near the pipeline because they cannot cross it. She also reported that, during construction, children died when playing on the half-completed pipeline. According to Ajout Along, there was no awareness-raising on health and safety for the local communities. Sham Compensation In acclaiming the discovery of the Paloich oil fields (“a petroliferous system with extremely rich oil and gas reserves”) as its greatest scientific and technological achievement of 2003, the China National Petroleum Company stated, “the discovery cost per barrel is much lower than that for big international oil corporations, yielding both high exploration and social benefits.” By lack of publicly available data, the cost-efficiency of Petrodar’s operations cannot be independently judged. All available evidence, however, indicates that the development of the Melut Basin has brought no substantial social benefits, but has rather taken the desperately poor area backwards. Northern Upper Nile is extremely poor by any standard. More than 90 percent of the population in Renk District live on less than $1 a day. Data available from UN nutrition surveys conducted in Melut county indicate persistent food shortages, with malnourishment rates of 20.5 percent in May 2002 and 28.1 percent in April 2005. Paloich, the main oil center, may serve as an example. Before 2001, Paloich was a small village that had a clinic run by foreigners, with free treatment for the poor. Today’s clinic is larger and better equipped, and almost exclusively for army use. The Dinka population is obliged to sell goats to buy medicine, and has no other option now but to treat themselves. So few facilities are in the area that the local Dinka have been crossing to SPLM/A-controlled areas in search of medical care. A universal complaint from residents is the lack of basic services in the area. Production areas have electricity, but no indigenous population to use it. Rural settlements and camps for the displaced — where people do live — have no electricity. Oil centers like Adar and Paloich have clinics, but local people say they cannot access them, unlike oil workers and the military. Paloich has an important up-to-date airport, but its population has no fresh water, no jobs and no security. No compensation has been offered, other than a patch of barren black cotton soil a few kilometers from Paloich, where Petrodar has built a police station (occupied by Northern police, even though it is in the South), a mosque (in an area where the people are non-Muslim), a school (also occupied by Northern police) and a hospital (without doctors or patients). People have refused to move there because they know it floods in the wet season. There are piles of rotting reeds stored in the school — this is Petrodar’s contribution to housing. Local people are outraged, especially as they have heard that Northerners displaced by dams and other projects are given ready-built concrete homes as compensation. Basic services such as health and education are almost non-existent in the Adar Yel oil field. Security for Oil, Not People Security in the area is still provided by Northern forces taking their orders from Khartoum rather than Juba, the regional capital of Southern Sudan. Melut is one of the few places in Southern Sudan where mounted heavy weapons, with ready-use ammunition stacked next to them, are visible. They are stored in a church compound that government of Sudan forces occupied in 1997 and have refused to hand back. In the south of bloc 7, government and militia forces are reported to have been militarizing the Sobat river. International observers say that at least nine government garrisons were established on the Sobat in the first half of 2005. They are “described as town halls, community centers and such, but clearly [are] not!” said Rev. John Aben Deng in April 2005. Rev. Deng, who made a fact-finding trip to the region for the European Coalition on Oil in Sudan, says everyone blames oil development for the militarization. “Why is the government building new garrisons on the Sobat?” he asks. “To occupy and secure the oil area and to protect the companies because the communities are against the drilling of the oil.” Local SPLM officials believe that Petrodar has colluded with Sudanese government security forces, who still restrict the movement of local people. Petrodar now wants to expand south of the Adar River, but local authorities and traditional chiefs are trying to block this, and want the decision referred to Government of Southern Sudan in Juba, not to the Northern Islamic Front (NIF)-dominated Government of National Unity in Khartoum. They say that oil has only brought destruction north of the river; why should the same destruction be allowed to spread? Empty Promises? More than a year after the signing of the Sudan Comprehensive Peace Agreement, conditions for impoverished civilians have improved only minimally. Most of the displaced in northern Upper Nile have little or no knowledge of the peace agreement. Those aware of it believe that, because it promises peace, it must provide for an immediate end to the abuses they associate with oil, safe return to their villages and development. “We have heard about peace, but seen nothing,” says Chief Chol Nul, a chief of the Dinka Nyiel in Adar. “I want to see a big hospital, schools, roads, free movement to Malakal and Renk without government militias on the way. The CPA [should mean] employment, no hunger, hospitals and schools, no fear and UN troops on the front lines to monitor the ceasefire and the oil. Then there will be peace.” In a number of areas, local people are taking matters into their own hands. In Det, south of Guelguk, where an exploratory well was dug in 2004, civilians killed the Petrodar team leader in January 2006, within a fortnight of the CPA being signed, and chased away the government-backed militia of Jok Deng. “North of the Sobat,” says Rev. John Abeng Deng, “the Dinka agreed that anyone doing oil work south of Khor Adar would be killed. They want oil development stopped until it is done with their agreement.” In many parts of the Petrodar concession, chiefs and civilians have asked the SPLA to arm them to enable them to return to their homes despite the continuing presence of government-supported militias. Paramount Chief Deng Nuor is one of them. “We want to go back to our villages,” he says. “If we are not helped to do so, we will fight the militia to settle in our villages. We have asked the SPLA for weapons. But we have been told: ‘There is peace. We don’t want fighting.’” Egbert Wesselink is coordinator of the European Coalition on Oil in Sudan (ECOS) and Evelien Weller is research officer at ECOS. They work with Pax Christi Netherlands. ECOS is a group of over 80 European organizations working for peace and justice in Sudan. The coalition calls for action by governments and the business sector to ensure that Sudan’s oil wealth contributes to peace and equitable development. This article is based on an ECOS report, “Oil Development in Northern Upper Nile, Sudan.” ****** THE SPECTER OF STATE OIL COMPANIES In the 1980s, the outbreak of war forced Chevron and Shell to leave Sudan. In recent years, Western companies including Talisman and OMV have been forced to leave the country after numerous accusations of widespread human rights violations, which involved the Sudanese government driving people out of areas surrounding oil production facilities. Asian companies from China, Malaysia, Russia and India have stepped in to fill the void. Sudan’s oil industry is currently dominated by state-controlled companies, prime among them CNPC (China), Petronas (Malaysia) and ONGC Videsh (ONGC, India). These companies are increasing oil production steadily, which rose to 304,000 barrels a day in 2004, up more than 10 percent from 2003. Projections for 2006 range from 434,000 to 600,000 barrels a day. One new fear is that the home country governments of the companies will exercise diplomatic influence to undermine international efforts to secure peace and justice in the country, when such efforts contravene the interests of the Northern-dominated Sudanese government. China especially needs monitoring. Sudan is a major source of oil for China. As a veto-wielding member of the UN Security Council, China has sabotaged attempts to put pressure on Khartoum to end the Darfur genocide. — E.W. & E.W. |

|||

|

||||