Tsunami's Legacy: Extraordinary Giving and Unending Strife

by Somini Sengupta and Seth Mydans, The New York Times, December 25, 2005

JAFFNA, Sri Lanka - Charity came pouring in from far and wide for this island nation devastated by the tsunami a year ago. But on its fragile northern peninsula, Udayarani Sebastian Pillai today lives on the cliff-edge of uncertainty.

Villagers rebuild a Catholic church destroyed by last year's tsunami into a memorial earlier this month in Mullaittivu, Sri Lanka

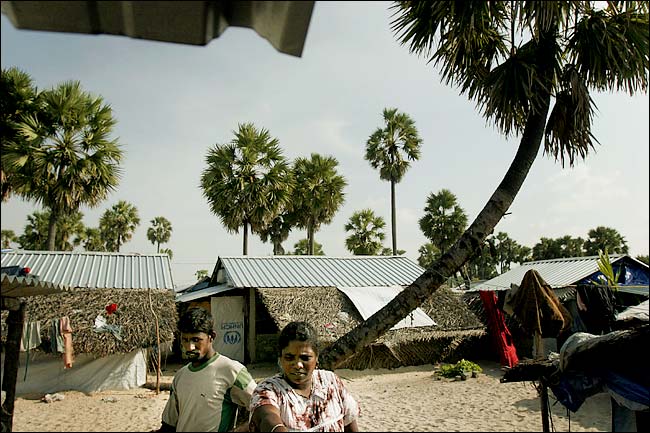

The government has barred her from rebuilding on the seafront where she had lived, and there is no promise of a permanent house. For now, home is a transit camp sandwiched between army and rebel lines. From beyond the camp comes news of a possible renewal of civil war. Her mind remains ravaged: the tsunami killed three of her seven children.

At first, the tsunami seemed to dangle the hope of reconciliation. It struck both government-held land and territory controlled by the Tamil rebels, and it brought the two sides together to heal and divide aid. Today, squabbles over aid combined with the legacy of recrimination have so worsened the conflict that Sri Lanka seems closer to war now than it has at any time since the peace process began nearly four years ago. Clashes between government troops and suspected Tamil separatist rebels have become routine.

Members of the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam walked near destroyed homes in their territory. Along with Sri Lanka and Indonesia, the Tamil Tigers have prohibited new housing in their territory to be built on the seafront.

This is not what might have been anticipated a year ago, but it is only one of a wide range of contrasting and often paradoxical effects being felt a year after the tsunami killed 181,000 people as it devastated the coastlines of Sri Lanka, Indonesia, India, Thailand and other countries around the Indian Ocean. The looming threat of war in Mrs. Pillai's country, in fact, stands in stark contrast to the extraordinary shift 1,100 miles away, in the Indonesian province of Aceh. There, Muharram Idris, a former rebel commander who watched as the sea swallowed his village and family, now scoots around on a red motorcycle, tending to the business of peace. The ethnic separatist guerrillas he once led have turned in their weapons and are retooling themselves as a political party. In Aceh, the tsunami and aid helped quiet a 30-year-old civil war.

Some tsunami survivors have additionally been displaced by the conflict between the rebel Tamil Tigers and the Sri Lankan government.

The tsunami of Dec. 26, 2004, was, of course, an extraordinary calamity. Apart from the stunning death toll, it displaced close to two million people, razed entire villages, submerged others forever, ruined some 2,900 schools, sundered families. The response was also extraordinary. The United Nations, usually accustomed to ranging across the world's rich countries with a begging bowl in hand to deal with emergencies, met its $977 million appeal within a month. Private aid groups roped in record donations. Doctors Without Borders raised so much that it eventually diverted some of the money to other, far more neglected emergencies, namely a food crisis in West Africa and the earthquake in Pakistan.

All told, the tsunami generated a record $13.6 billion in aid pledges, according to the United Nations. Just as rare, donor countries kept their promises. The United Nations Office of the Special Envoy for Tsunami Recovery says 75 percent of the $10.5 billion pledged for reconstruction of tsunami-affected countries has been secured; by comparison, independent studies have found that no more than 10 percent of aid pledges were honored after the 2003 earthquake in Bam, Iran.

Workers cleared an area before building a permanent new settlement inside territory controlled by the Tamil Tigers in Mullaittivu.

The progress report on relief and reconstruction is, however, mixed. And like the contrasting political fates of Sri Lanka and Aceh, the lessons for aid agencies are complex. In many respects, remarkable advances have been made. In Sri Lanka and Indonesia, nearly all tsunami-affected children are back at school. Swift intervention averted major outbreaks of disease. In Sri Lanka, 70 to 85 percent of adults who lost their livelihoods have regained their main source of income, and 41 of the island's 52 damaged hotels are open for business, according to a report prepared jointly by the United Nations and the government.

A tsunami early-warning system in the Indian Ocean - which might have saved countless lives last year - should be ready for installation in mid-2006, the World Meteorological Organization says. The intent is to prepare every country's weather service to receive updates and warnings on a range of climate and weather shifts within two minutes of their occurrence.

In Sri Lanka, nearly all of the displaced survivors have been moved out of tents and schools and are housed in shelters designed to last up to two years

Yet many hurdles remain. Of the 1.8 million made homeless last year, only one in five are in a permanent home, a survey by the aid agency Oxfam has found. Some 67,000 Acehnese are still languishing in tents. The vast majority are in charity-financed shelters designed to last another year or two at least.

The deluge of tsunami aid has actually yielded a paradox of plenty, and money itself, or how to share it in the case of Sri Lanka, has widened the divide. Local residents have sometimes been paid well beyond the going wage rates, for everything from removing rubble to clearing jungles. Fishermen have been given boats, but on occasion, more boats have been gained than lost, raising fears of overfishing. The shortage of available land has delayed permanent housing construction and the inflow of foreign aid has sharply driven up prices. In Sri Lanka, the cost of a new house has at least doubled, while in Aceh, where half a million people have been displaced, rents have risen as much as tenfold.

Cows rested on the beach within feet of ruined structures in Mullaittivu.

Reconstruction has already felt the impact of coming war and peace. In Sri Lanka, the tensions have begun to slow aid operations. In Aceh, fighting halted in part to allow aid groups to work in safety.

In Sri Lanka, the outpouring of tsunami aid has prompted some charities to take a hard look at whom to help. The tsunami made 458,000 people homeless; the 20-year-long war in Sri Lanka displaced 341,000.

"If you go into an area where you have a whole bunch of have-nots and you help half of them, you're going to entrench some serious problems down the road," Paul Shanahan of the Australian Red Cross argued. "The principle of impartiality is that you respond to the greatest need." In deference to that principle, the Australian Red Cross is rebuilding houses for four villages in the country's ravaged north coast: two for families displaced by war, two others nearby for those displaced by the tsunami.

"It's not like I had to struggle with a scarcity of resources," Mr. Shanahan said. The International Federation of Red Cross raised a record $2 billion for tsunami aid.

Reinventing a Society

In Aceh, construction officials say the scope of the devastation has given them a chance to do more than build new houses. "We want to transform Aceh to become an open, aggressive, progressive society - not isolated and not only looking to the past," said Kuntoro Mangkusubroto, who heads the Indonesian government's Reconstruction and Rehabilitation Agency.

Actually, restoring what stood before is next to impossible. In many cases, landmarks have vanished, title deeds have washed away. The huge death toll has changed the shape of local populations.

"If five villages each had 1,000 people and they each have 100 now, do you need separate villages now, separate schools, separate community centers, separate mosques?" asked Jonathan Simon, who heads a reconstruction project in Aceh for the United States Agency for International Development.

Mr. Kuntoro's target is to move everyone from tents and temporary barracks into permanent houses by 2007. Some aid agencies are preparing for a much longer timetable. The International Organization for Migration, for instance, says some of the temporary barracks would be refitted to last for 5 to 10 years.

Amid the ruins of the tsunami, frustrations run high. Homeless people tell stories of foreigners arriving with promises and then disappearing. "They promised 'as soon as possible,' but that was June, and we never heard from them again," said Mahdani, 31, a fisherman, standing next to small piles of sand and stones a group had left behind for construction. "All we have is promises, ya, ya, ya, ya."

Some 480 aid groups are registered here and Mr. Kuntoro said he would soon expel those that have failed to provide real help.

The single largest impediment to putting up permanent homes is the question of whether to allow people to return to the edge of the sea. Both Indonesia and Sri Lanka - as well as the Tamil Tigers in their own territory - have prohibited new housing on the seafront, forcing builders to hunt for new land and delaying reconstruction schedules.

Consider the experience of the United States charity, Catholic Relief Services and its local partner, Caritas. In Galle, on the southern coast of Sri Lanka, the group promised to put up 126 houses. The originals all fell within the buffer zone; new land had to be found for all. Money was no object, and expectations ran high. The agency was optimistic that construction could begin by midyear. But the land offered by local government officials was either swampy or hilly. On some parcels, there were outstanding legal claims by private landowners. In early December, even when land issues were resolved, local authorities had not yet finalized the list of families who were supposed to receive houses. At one point, there were fewer beneficiaries than houses to be built.

Meanwhile, skilled engineers and masons became scarcer and more expensive, driving construction costs skyward. A 500-square-foot house of concrete is priced at $7,500 now, up from less than $5,000 in April, when initial estimates were done. (In the rebel-controlled town of Mullaittivu, a house of the same size can cost up to $10,000.)

"It's not a straightforward exercise," said Anne Bousquet, the Sri Lanka country representative for Catholic Relief Services. "Just because thousands of houses are washed out, you can't just put thousands of houses back up. It takes time, as we are seeing in places like New Orleans as well."

Aid workers are keen to point out progress. In Sri Lanka, nearly all of the displaced have been moved out of tents and schools and, like Mrs. Pillai in Jaffna, housed in shelters designed to last up to two years. Drainage pipes are being laid in new villages, hospitals built where none existed, nearly half of the 32,000 homes that stood inside its buffer zone have been or are being built. In Indonesia, construction is under way or completed for nearly a fourth of the 100,000 homes that need to be replaced, according to the World Bank. Some 1,500 new teachers have been trained.

Disaster, Then a Deal

Irwandi Yusuf, 45, a senior official in the Free Aceh Movement, was locked in a government prison last Dec. 26, when the early-morning earthquake shook its walls. He heard the roar of the waves and clambered to the roof, punching a hole in the asbestos ceiling. He was among 40 prisoners who survived, he said; 238 died.

The Free Aceh Movement eventually struck a remarkable deal with the Indonesian government. Under an internationally supervised peace accord, the rebels say they have turned over most of their weapons. Some 1,400 political prisoners have been released from jail. Foreign donors are paying for the reintegration of 3,000 former guerrillas into civilian life. Mr. Irwandi is now Free Aceh's spokesman. Of the peace process, he said, "So far so good."

The next step is the passage of a law by the Indonesian legislature to allow his group to contest provincial elections. Without that, Mr. Irwandi said, the accord could collapse.

Today, even as reconciliation takes root, both sides eye each other warily. The military mistrusts the rebels' claim that they have given up their arms. The rebels refuse to produce a list of their 3,000 fighters until they are confident that peace will hold.

As for the promised aid to former fighters, Mr. Irwandi scoffed at the idea. "How could they provide jobs when there are no jobs here?" he demanded. "It's not real."

In any case, the tsunami's devastation overwhelms attempts to return to normality. Mr. Irwandi pointed to the case of Mr. Muharram, the rebel commander who had stood on his hilltop hideout on the morning of the tsunami. Of the 7,000 residents of his village, only 600 survived. Mr. Muharram was orphaned, widowed and homeless. "With whom will he reintegrate?" Mr. Irwandi asked. "All his village was washed away."

Why did the tsunami engender peace in one country and not in another? Several things seemed to work in Aceh's favor: political arguments shrank in the face of a shared disaster, a long-closed society opened up to a flood of foreign aid workers, the olive branch extended by the Indonesian president, Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono, a former general, inspired trust. Above all, people in Aceh said, everybody on all sides had already grown sick of war by the time the tsunami struck. Over 30 years, the conflict had killed 15,000 people.

For Azwar Hasan, a social worker in Aceh, the shock of the tsunami was one thing. But returning to war was another. "I lost 10 family members, and of course that is not easy," he said of the tsunami's toll. "But time goes by, and I will accept it. That's life and death."

"But imagine living in a conflict area and never knowing what is going to happen to you, or happen to your mother or father or sister or child," he went on. "You can lose everything at any time. Nobody wants to go back to that situation."

After the Fury, Hope Dashed

In Sri Lanka, so mighty was the ocean's fury on that Sunday morning last December that it chastened, at least for a while, the most bullish hearts. It was the first time, said Chandra Jayaratne, 58, that he saw people in his country rally not as southerners or northerners, nor as ethnic Tamils or Sinhalese, but as Sri Lankans.

The optimism largely rose and ultimately fell on the proposal to share a portion of foreign reconstruction aid between the government and the rebels. Talks on aid-sharing began within weeks; both sides embraced the idea. But as talks dragged on, they got bogged down over questions of sovereignty and self-rule - the very questions that held up a political settlement for all these years. Sinhalese ethnic nationalists in the South denounced the aid-sharing. By the time a deal was finally hammered out, in late June, the Sinhalese nationalist party had pulled out of the government. The Supreme Court struck down crucial provisions. The Tamil Tigers accused the government of bad faith.

In August came a violent turning point: the assassination of the Sri Lankan foreign minister, Lakshman Kadirgamar. In November, in a brazen display of power, the Tamil Tigers enforced a boycott of presidential elections, buoying the victory of a hard-liner Sinhalese candidate and an outspoken opponent of the aid-sharing deal, Mahinda Rajapakse. In December came repeated strikes against the military. [and many killings of civilians -- Editor] Over a 10-day period, one military truck was struck by a land mine, another by a remote-controlled bomb, grenades were hurled at an army base, and a military helicopter was shot at and forced to land. The government accused the Tigers in each incident; the Tigers denied responsibility.

[Three days before the first anniversary of the tsunami came the most serious violation of the February 2002 cease-fire accord: 13 Sri Lankan Navy sailors were killed by a land mine planted by people suspected of being Tamil Tiger rebels.] [Killings of LTTE members, you see can be plausibly denied by the government because they blame all such incidents on the paramilitaries and the international community believes them. -- Editor]

The leader of the Tamil Tigers political wing, S. P. Thamilchelvan, in an interview in early December declared that frustrations had a reached a tipping point. "The responsibility is with Colombo to realize the gravity of the situation," Mr. Thamilchelvan declared. "If war is unleashed on the people, then the responsibility to safeguard them, defend them and fight against oppressive tactics is with the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam. It is a state of ever-preparedness."

At the very least, the tsunami has delayed a return to conflict. The more gloomy analysis suggests that the disintegration of the aid-sharing deal, combined with elections, has heightened the bitterness. On paper, a cease-fire holds. But Sri Lanka looks closer to war than at any time since the accord was signed in 2002. "It is a grim situation, volatile, ready to implode," said Irene Khan, the secretary general of Amnesty International, during a recent visit to the capital, Colombo.

Insecurity in the north and east has begun to stymie aid work. Grenade and bomb attacks have grounded teams going into the field. "You don't want to be caught at the wrong time in the wrong place," the head of the United Nations refugee agency in Jaffna, Agron Drajaj, said in an interview. "Our work in the field is being pulled back."

Today a tense uncertainty prevails. One day in early December, along the main road that leads to the displaced peoples camp where Mrs. Pillai now lives, a car had been set alight at a busy intersection. A few miles behind, on the same road, lay the grisly remains of an army tractor, blown to bits by a pair of remote-controlled bombs, killing seven. "The tsunami gave us an opportunity to forget it all and have a new beginning," said Mr. Jayaratne, an insurance executive who volunteers with the country's largest development group, Sarvodaya. "We have squandered the opportunity and grown apart. We had a golden moment of unification. In the first few days, you didn't hear people saying, 'Whose body is this?' "

Somini Sengupta reported from Sri Lanka for this article, and Seth Mydans from Indonesia.

|

Home

Home Archives

Archives Home

Home Archives

Archives