Wonderful World?

The Number of Conflicts Worldwide Decreased

by James Traub, The New York Times

|

In fact, the authors of the study argue that "the single most compelling explanation" for the decrease in conflict is that preventive diplomacy and peacemaking missions, as well as UN peacekeeping operations, which had been almost impossible to mount during the cold war, now accompany almost every major crisis.

|

We live in a world that is objectively more dangerous than the one we knew at the outset of the millennium; whatever our disagreements, since 9/11 both our foreign policy and our domestic politics have pivoted around this ineluctable fact. And because the terrorists who struck us represent a global phenomenon, we assume that the world is objectively more dangerous for everyone. But is it?

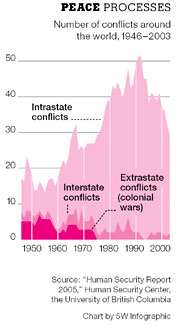

The answer, it seems, is no. In recent years, scholars have been gathering data in an attempt to measure global trends in conflict and violence. The emerging view is that conflict worldwide is in fact diminishing, not growing. According to "Human Security Report 2005," a study that relies on this recent scholarship, the number of armed conflicts has been dropping steadily since the end of the cold war. Major civil wars, which exploded around the world between 1946 and 1991, declined sharply in the ensuing decade. Indeed, the trend holds true for virtually every category of conflict — coups, interstate wars and even genocides and so-called politicides, in which political belief rather than ethnicity is the criterion for killing. The only exception is international terrorism — as we know all too well. The answer, it seems, is no. In recent years, scholars have been gathering data in an attempt to measure global trends in conflict and violence. The emerging view is that conflict worldwide is in fact diminishing, not growing. According to "Human Security Report 2005," a study that relies on this recent scholarship, the number of armed conflicts has been dropping steadily since the end of the cold war. Major civil wars, which exploded around the world between 1946 and 1991, declined sharply in the ensuing decade. Indeed, the trend holds true for virtually every category of conflict — coups, interstate wars and even genocides and so-called politicides, in which political belief rather than ethnicity is the criterion for killing. The only exception is international terrorism — as we know all too well.

The study, issued by the Human Security Center, a policy institute at the University of British Columbia, is not entirely convincing. Because, for example, no sound metric exists for tallying them, the "indirect deaths" caused by conflicts that uproot vast numbers of people, disrupt agriculture and shatter health-care systems have not been counted.

Nevertheless, once we get past our initial disbelief, the notion that we live in an era of comparative peace shouldn't be so surprising. Colonial struggles largely ended by the mid-70's. Cold-war proxy battles also ended. And over the last decade or so, the international community has developed a set of mechanisms to put the brakes on incipient warfare. In fact, the authors of the study argue that "the single most compelling explanation" for the decrease in conflict is that preventive diplomacy and peacemaking missions, as well as UN peacekeeping operations, which had been almost impossible to mount during the cold war, now accompany almost every major crisis. As a result, outright warfare is now concentrated, albeit to an extraordinary degree, in one area — sub-Saharan Africa. Entire regions that were strife-torn 20 or 30 years ago, including East and Southeast Asia, are largely peaceful today. North Africa is quiet; Latin America suffers from political instability but not warfare.

|

| French special forces under U.N. mandate keeping the peace in Congo, June 2003 |

This is certainly good news, especially for the beleaguered United Nations. But it does nothing to relieve our own sense of vulnerability, since terrorists are not amenable to negotiation or peacekeeping. You can, therefore, draw a troubling inference from the data, which is that for all the talk of "globalized" threats, the American experience of the world is becoming less, not more, similar to that of our allies and trading partners. Our world has become more dangerous; theirs, with some important exceptions, less so.

Why is it so hard for Americans to recognize how very different the world appears when seen from beyond our borders? The authors of "Human Security Report" hypothesize that myths about a rising tide of violence propagated by the media or international organizations "reinforce popular assumptions." O.K., but why the popular assumptions? Why are our intuitions about both the past and the present so far from the reality?

The answer has to do with fundamental differences between the cold war and the Age of Terror. In the cold war, the chief combatants never fought one another — thus the "coldness" of the war between them. The rest of the world was aflame with proxy combats, but the fear of provoking nuclear war served as a heat shield for the West. The authors of "Human Security Report" note that the scholarly description of the post-World War II era as the "long peace" is "deeply misleading." But psychologically it was accurate.

Now the relationship between threat and actual fatalities has been reversed. International terrorism has killed an average of 1,000 people a year over the last 30 years, according to "Human Security Report." That's not a lot. But the threat of terrorism is out of all proportion to its lethality; that is, in a way, the whole point of terrorism. It is true that since 9/11, nothing has happened in the United States, but anything can happen, anywhere, at any time. And of course something has happened. We all had nuclear nightmares in the depths of the cold war, but we recognized them as nightmares, or as scenes from apocalyptic movies. Yet in the case of terrorism, we had the apocalypse before we even had the nightmare. And so while we may accept the idea that we live in a less-war-torn age, the mind rebels at the thought that we live in a less dangerous age.

But that's us; it's not even "the West." In his famous essay "Of Paradise and Power," Robert Kagan argued that Europeans have stepped out of the Hobbesian world of anarchy — our world — into their own Kantian world of "perpetual peace." With Islamic terrorism a growing threat in Europe, Kagan's Mars/Venus distinction may not be quite as salient as it seemed. But outside the West, where in general the world really does feel less lethal than it used to, President Bush has had a very hard time enlisting allies in the war on terror. Many developing nations would rather talk about development and trade than about sleeper cells. Yet we need their help in the fight against terrorism.

The Bush administration has discovered the hard way that diplomacy is more difficult today — and arguably more important — than it was during the cold war. You can only hope that this discovery points toward a wiser and more supple view of the world we have been forced to inhabit.

James Traub, a contributing writer to The New York Times, is completing a book about Kofi Annan and the United Nations.

|

Home

Home Archives

Archives Home

Home Archives

Archives