Ever heard of AFSPA, PTA, TADO, ATA?

How security laws categorise citizens in India, Nepal, Pakistan and Sri Lanka.

by Kaushiki Rao, Himal, March-April, 2006

|

[S]ecurity laws often go against citizen interests, and are problematic in two ways. First, they give immunity to the arbitrary actions of the police and armed forces, contravening basic legal principles. Second, they are selectively applicable, either in particular areas or to particular groups of citizens. It is these citizens who face the arbitrary abrogation of their human rights and civil liberties.

|

In the Name of Security

Are security laws inherently undemocratic? Such laws violate fundamental rights as enshrined in both national and international statutes, including those as significant as right to life and bodily safety, representation before the law, and the prevention of arbitrary detention. Yet democracies continue to support and endorse security legislation, which in Southasia functions by dividing each country’s citizens into the deserving and the undeserving. Those in the former category merit the trust and protection of the state, while those in the latter do not. It is this systematic segregation of citizens that allows for the targeting of particular groups, curtails civil liberties and infringes on individual rights.

In a democracy, an elected government is supposed to be representative of its citizens’ interests, and everything done by a democratic government is done in the name of the electorate. Correspondingly, any law that a democratic government legislates in its own interest is in fact legislated in the interest of the state’s citizens. Security laws promulgated within a democratic state are no exception to this rule; governments explicitly declare that such laws are necessary for the safety of citizens. In a democracy, an elected government is supposed to be representative of its citizens’ interests, and everything done by a democratic government is done in the name of the electorate. Correspondingly, any law that a democratic government legislates in its own interest is in fact legislated in the interest of the state’s citizens. Security laws promulgated within a democratic state are no exception to this rule; governments explicitly declare that such laws are necessary for the safety of citizens.

Nonetheless, security laws often go against citizen interests, and are problematic in two ways. First, they give immunity to the arbitrary actions of the police and armed forces, contravening basic legal principles. Second, they are selectively applicable, either in particular areas or to particular groups of citizens. It is these citizens who face the arbitrary abrogation of their human rights and civil liberties.

How these citizen categories are created can be explored through security laws from four Southasian countries – India, Nepal, Pakistan and Sri Lanka. It is important to note that each of these laws was initially enacted in democratic situations, although they continue to be applied in the currently undemocratic states of Pakistan and Nepal. Moreover, these laws have been widely used in each country, even while domestic and international human rights organisations denounce them

as contributing to human rights abuses.

Four laws

One of Southasia’s earliest security laws, India’s Armed Forces (Special Powers) Act (AFSPA) was legislated in 1958 in order to protect citizens against separatist militants in Assam and Manipur. Applicable to those areas that the central government declares ‘disturbed’, it is currently operational in several areas in Northeast India. No emergency needs to be declared for this law to be in force, which contravenes provisions of the International Convent on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR). The AFSPA empowers the armed forces – including the navy and the air force – to arrest, detain and search any “suspicious person”. Security forces are not obliged to explain the grounds of the detention to anyone, nor is there an advisory board in place to review such arrests. Moreover, the AFSPA empowers the armed forces to shoot-to-kill “suspicious” persons. Finally, without permission from the central government, no legal proceedings can be initiated against anyone in the armed forces acting under AFSPA.

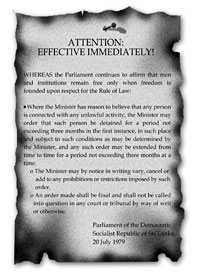

Sri Lanka’s Prevention of Terrorism Act (PTA) was legislated in July 1979 to empower the security forces to combat anti-state forces. In 1984, the International Commission of Jurists had said, “No legislation conferring even remotely comparable powers is in force in any other free democracy operating under the Rule of Law.” The law, however, continues to be in force. Applicable throughout the country, the Ministry of Defence has the power to declare specific regions as security areas. The PTA is in direct contravention of the ICCPR, as it can be instituted outside of a state of emergency and applied retrospectively. It was also deliberated at the Sri Lankan Supreme Court, which declared that while fundamental rights may be restricted through security laws, they cannot be completely denied.

The PTA empowers the police to search or arrest reasonably suspicious persons without a warrant, who can then be detained by the Ministry of Defence in three-month increments for up to 18 months without access to lawyers or relatives. Moreover, the process does not need to involve the judiciary at all, and detainees are not allowed to petition any court. The Defence Secretary can issue a Rehabilitation Order, by which a person can be detained indefinitely. The PTA also guarantees state officials immunity from prosecution for any actions taken under the Act.

Pakistan’s Anti-Terrorism Act (ATA) was legislated in 1997 by the Nawaz Sharif government, despite strong protests from opposition parties. It has been amended several times, most recently in 2004. The legislation has often been used to act against opposition party members. The ATA authorises the government to declare any group or association of people unlawful, and overrides all other protective legal provisions. Based upon their own judgment, both police and army officials are empowered to use “necessary force” and “shoot to kill” to prevent anti-state activities, which include threatening actions, use of arms or explosives, disruption of mass services like electricity, as well as rape and trespassing. Pakistan is not a signatory to the ICCPR.

Only anti-terrorism courts – specially established by the government – can try people indicted under the ATA. Such trials must be conducted within seven days, while appeals must be filed and heard within additional seven-day periods. Judges are enjoined to serve the maximum sentence – if a shorter sentence is passed, they are required to explain the rationale for the judgement. Anyone suspected of conducting anti-state activities must sign a bond allowing the police to search not just the suspect’s property, but also that of his family. Under the ATA, both police and army are immune to prosecution, so long as they have conducted their acts in “good faith”.

In Nepal, several similar laws were in place before the Terrorist and Destructive Activities (Control and Punishment) Ordinance (TADO) was promulgated in 2001. The ordinance ran for six months before being extended into a two-year act (TADA) by the Parliament. Since then, TADO has been reintroduced in Nepal every half-year. TADO is to be applied either to select groups or to select areas by government declaration. Although both the police and army are empowered to act under this ordinance, it is only the police who are allowed to hold detainees in custody. TADO allows for six months of preventive detention without trial, which can be extended for another six months with the approval of the Home Ministry, rather than from the judiciary. TADO cases are tried by special courts set up by the government, and there is no statute of limitations for such cases. The police and army are again given immunity for any actions carried out under this law. Moreover, security personnel injured in any way while enforcing TADO are entitled to government compensation.

State selectivity

In general, security laws are legislated in order to address aggression against the state, such as by separatists in Northeast India, the LTTE in Sri Lanka or the Maoists in Nepal. Pakistan’s security laws are commonly believed to have been created and used in order to consolidate political power. While governments justify security laws as essential for the protection of the state, they also claim that the laws are meant to protect the citizens. But the fact is that security legislation pits the state against its own citizens. Both nationally and internationally, the laws of the four countries listed above are considered excessive, not only because they abrogate human rights and civil liberties, but also because they go against national constitutions and international treaties. Moreover, the vague wording generally found in security legislation poses a further threat to civil liberties, with Amnesty International maintaining that such laws are “broadly formulated, and extend beyond legitimate security concerns.”

The selective application of security laws opens up the space for discrimination. The AFSPA in India, for example, applies only to the Northeast; the PTA in Sri Lanka is applicable only to the north and east of the country. Although not all citizens in these areas experience preventive detention or search without warrant, they do experience the law’s threat to a much greater extent than do citizens elsewhere. During legislative debates in India, the AFSPA was justified as a means of maintaining the territorial and cultural unity of the country. Those who opposed the act, on the other hand, argued that the means by which it attempts national integration is a violent one.

Citizen distrust

Security legislation also discriminates between particular groups of citizens – pitting those who act to maintain the status quo against those who push for change. Citizens who are categorised by the state as a possible threat to security are obviously more likely to have their civil liberties curtailed by these laws. There are two ways in which security laws discriminate between groups of citizens.

First, security laws allow police and armed forces to act with impunity. That such personnel cannot be brought before the court for their actions indicates that the state encourages and protects them at the expense of other citizens. Vague words such as appropriate grounds, reasonable suspicion, reasonable apprehension, convinced, suspicious persons, due warning, appropriate force and the like are rife in security legislation and have the effect of allowing security forces excessive discretion. Moreover, the motives of the armed forces or police are rarely questioned. Acts done in good faith cannot be judicially investigated – even while human rights organisations claim that such powers are regularly abused, with immunity clauses (which breach UN recommendations) often used to detain and torture suspects. In Sri Lanka, for example, those detained under the PTA are often kept beyond the maximum period through a Rehabilitation Order; many who have been detained in this manner have made allegations of police torture. When the Indian army soldiers raped and killed a woman in Manipur last year, they took shelter under the AFSPA. Despite widespread protests, the Act remains in force. State agents subsequently enjoy not just the state’s full trust, but are essentially treated as citizens more equal than others.

The second way in which security laws discriminate between groups of people is by questioning the reasons, motives and actions of selected segments of the citizenry. Through the provision of preventive detention, authorities can detain and search some citizens without warrant; refuse them access to courts, lawyers or family; and can even shoot to kill. Moreover, preventive detention means that these citizens are always assumed to be guilty until proven innocent, contravening the ICCPR. As greatly as the state trusts its security personnel, so little does it trust or protect the rest of its citizens.

It is important to note that the degree to which each citizen is questioned depends on his social position with respect to the state. This leads to a systematic segregation of those citizens who deserve the protection of the state and those who need less of it. For example, a Tamil in Sri Lanka will more easily acquire a ‘suspicious’ status in the eyes of the government than will a Sinhalese. In Nepal, a person from a Maoist-influenced district such as Rolpa or Rukum will be more ‘suspect’ than one from elsewhere. In Pakistan, a person who sympathises with a particular political party would have been more likely to be considered ‘suspicious’ when an opposing party was in power; and now under the military regime, all members of independent political parties are more suspect.

India’s AFSPA bill, for instance, appears to have been introduced not just to give authority to and to protect the army, but also to protect the people of Assam and Manipur. During the AFSPA debates in the Indian Parliament, MP Rungsung Suisa said: “In order to save the Nagas themselves from the hostile and ruinous actions of their own brethren, it becomes necessary for the government to arm themselves with powers.” Such a statement groups the citizens of Assam and Manipur into two types – compliant civilians who require the protection of the Indian government, and non-compliant militants who deserve punishment from the Indian government. This dichotomy helps New Delhi legitimise the act of taking unconstitutional action against those citizens they term militants; since such groups are understood to endanger other citizens, the state can claim to have the responsibility to quell them. Moreover, throughout the parliamentary debates around AFSPA, militants were described with the use of infantilising adjectives such as mischievous, irresponsible, unreasonable and wanton. Such rhetoric serves to give the state patrimonial authority over those who are considered militants, and continues to differentiate between those citizens who are deserving of protection and those who are not.

Security laws, then, only ostensibly protect citizens. Those citizens deemed ‘trusted’ are given impunity for their actions or are unlikely to be affected by security laws. The ‘untrustworthy’, on the other hand, are affected to varying degrees by security legislation. The injustice in these laws lies not only in the arbitrary and excessive derogation of human rights and civil liberties, but also in this systematic segregation of a democratic state’s own citizens.

|

Home

Home Archives

Archives Home

Home Archives

Archives