Tamil Families Take to the Sea to Flee Horror of a Savage War

by

Ashling O'Connor, The Times, London, September 12, 2006

|

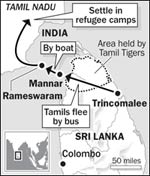

Since January more than 13,000 Tamils have completed the treacherous 20-mile voyage from Mannar to Rameswaran, a temple island in the southern state of Tamil Nadu, where they are dropped on Kodiakkarai beach to eke out an existence alongside 59,000 others in government-run refugee camps.

|

Refugees have drowned as they sail to India on rickety fishing boats

Indian fishermen dashed to help terrified refugees out of boats that rescued them from a sandbank where they had been ambushed by Sri Lankan boatmen (TOM PIETRASIK / CHRISTIAN AID) |

WITH their worlds wrapped up in plastic bags, thousands of Sri Lankan refugees are risking their lives by crossing the Palk Strait to India to escape the fighting ravaging their homeland.

Since January more than 13,000 Tamils have completed the treacherous 20-mile voyage from Mannar to Rameswaran, a temple island in the southern state of Tamil Nadu, where they are dropped on Kodiakkarai beach to eke out an existence alongside 59,000 others in government-run refugee camps.

They have paid between 2,000 and 8,000 Sri Lankan rupees (£10 to £40) each, a small fortune, for their berth on a rickety fishing boat that may not make the journey in rough seas. Many drown when the vessels capsize or when the boatmen, panicked by a chasing Sri Lankan navy ship, dump them on a sandbar several hundred yards from the shore. Pathunamathan, 56, a fisherman from Trincomalee, and his wife and two daughters were lucky to be spotted yesterday by an Indian navy coastguard, who rescued them from such a predicament. His story reflects a worsening situation in an area that has been the focus of renewed fighting between the Sri Lankan Army and the separatist Tamil Tigers.

“We just left our house and ran,” he said, wet and shivering from his ordeal. “There is no secure place for Tamils.”

Packed on to trucks, the disorientated travellers are taken for questioning at the police station at Dhanushkodi before being found shelter in a camp where they receive a small government allowance.

The biggest of the 118 camps is Mandapam, originally built for the reverse journey in the 19th century when Tamils were sent to Sri Lanka by the British to work on the plantations.

Among its 7,000 inhabitants is Shantakumar, 32, a former driver for a Dutch refugee care centre in Kutcheveli. Clutching his daughter Dinogini, 11, he cries as he tells how he was unable to save his younger sister and her family from the 2004 tsunami. “I could not reach her,” he said. “I was trying to forget what I lost in the tsunami and then the fighting happened.” After a bomb blast on August 20, his brother was riding his motorcycle home and was pulled over for questioning by the Sri Lankan Army.

“They made him kneel down and they shot him in the head,” he said. “I saw it with my own eyes. Every time I think of it, I think I do not want to live in a country like that.”

Eight days ago he brought his wife and four children to India. They have joined people such as Udhayakumar, 18, who says that he left Trincomalee after his mother and elder sister were hacked to death by a Sinhalese mob after a bomb ripped through the town in April. “Whatever these people do to us, the Government is not bothered,” he said. “If the Sri Lankan Army treated Tamils equally we would not be here.”

So far this month officials have counted around 2,000 refugees but more are pitching up every day and there are unconfirmed reports that about 50,000 are waiting to follow. On Sunday at dusk two boatloads arrived despite the choppy sea and high winds. Most were from Trincomalee.

Mani, 40, and his wife and five children left all their possessions behind. The plastic bag of betel wrapped into his lungi, a wraparound cloth, was the only thing he had salvaged. Logeswary, eight months pregnant, had forsaken her husband, a Sinhalese.

The Tamil Nadu government has some sympathy with the refugees who share their mother tongue. The central Government too has reacted to their plight, committing 400 million Indian rupees in July.

The apparent inaction on the part of Sri Lanka has been used as a political lever by the Tigers to embarrass the Government in Colombo. In response to accusations of apathy, the Sri Lankan Navy in July burnt 75 fishing boats. It disrupted the flow of human traffic only briefly. The special constables at Dhanushkodi are used to the ritual of taking names and segregating families. “Every night it is like this,” said one.

While most refugees complain of relentless harassment by the Sri Lankan Army, some come with stories of persecution by the Tigers if they did not agree with their politics.

Sasikala, 28, fled after her husband, a leader of a rival Tamil group, was dragged out of his house by rebels, tied to an electricity post and shot. She sold her gold earrings in Mannar to pay for the boat trip to India but her parents could not afford to follow her.

The 2002 ceasefire is officially still in place but the thousands of Tamils fleeing Sri Lanka are evidence that the situation in the country is spawning a humanitarian crisis.

“These are the people caught in between,” said Chandarahasan, the founder of the Organisation for Eelam Refugee Rehabilitation, which is funded by Christian Aid to supplement the Indian Government’s relief effort

.

|

Home

Home Archives

Archives Home

Home Archives

Archives