Climate Fears for Bangladesh's Future

by Roger Harrabin, BBC, September 14, 2006

|

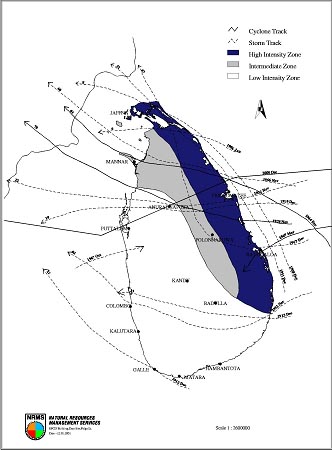

Rising water and the increased strength of storms will also affect our island, especially the NorthEast. See here and here for the beginning of work in this area.

|

Cyclone tracks |

Masuma's home is a bamboo and polythene shack in one of the hundreds of slums colonising every square metre of unbuilt land in Dhaka, the capital of Bangladesh.

Masuma is an environmental refugee, fleeing from the floods which have always beset her homeland but which are predicted to strike more severely with climate change.

She has found her way to the city from the rural district of Bogra - a low-lying area originally formed from Himalayan silt where the landscape is still being shaped by the mighty Brahmaputra river as it snakes and carves through the soft sandy soil.

"In Bogra we had a straw-made house that was nice. When the flood came there was a big sucking of water and everything went down," Masuma says.

"Water was rising in the house and my sister left her baby upon the bed. When she came back in, the baby was gone. The baby had been washed away and later on we found the body," she recalls.

'Climate refugees'

Masuma's story is already commonplace in Dhaka, the fastest-growing city in the world. Its infrastructure is creaking under the weight of the new arrivals. Climate change is likely to increase the risks to people like her.

Climate modellers forecast that as the world warms, the monsoon rains in the region will concentrate into a shorter period, causing a cruel combination of more extreme floods and longer periods of drought.

They also forecast that as sea level rises by up to a metre this century (the very top of the forecast range), as many as 30 million Bangladeshis could become climate refugees.

"Climate refugees is a term we are going to hear much more of in the future," observes Saleem-ul Huq, a fellow at the London-based International Institute of Environment and Development (IIED).

He says many Bangladeshi families escaping floods and droughts have already slipped over the Indian border to swell the shanty towns of Delhi, Bombay and Calcutta.

"The problem is hidden at the moment but it will inevitably come to the fore as climate change forces more and more people out of their homes.

"There will be a high economic cost - and countries that have to bear that cost are likely to be demanding compensation from rich nations for a problem they have not themselves caused," Mr Huq predicts.

It is a problem that incenses informed politicians in countries like Bangladesh, which are at the sharp end of climate change.

Environment Minister Jafrul Islam Chowdhury demands that rich nations should take responsibility for a problem they have caused.

"I feel angry, because we are suffering for their activities. They are responsible for our losses, for the damage to our economy, the displacement of our people."

The UK government is taking something of a lead in helping Bangladesh try to cope, by conducting a review aimed at ensuring that its international aid programme takes account of a changing climate.

The Department for International Development (DfID) believes that up to half its aid projects in the country could be compromised by climate change.

Tom Tanner, climate and development fellow at the Institute of Development Studies, Sussex, UK, is in Dhaka reviewing UK aid.

"We estimate that up to 50% of the (British) donor investment in a country like Bangladesh is at risk from the impacts of climate change," he says.

Shifting sands

DfID is already starting to modify some aid programmes for the poorest of the poor who make their homes on shifting silt islands in the great rivers of Bangladesh.

The islands - known as choars - last on average about 20 years. Then the inhabitants are flooded out, and need to seek new land created elsewhere by the highly-dynamic rivers.

Locals say siltation levels appear to have diminished, so less new land is being created.

|

We have nothing left, but we have to survive, so we've had to build our house from reeds

Pulmala Begum |

For Pulmala Begum, who lives on an embankment on the Brahmaputra, rebuilding has become commonplace; but each time she loses more. She has been displaced by flood waters six times.

"We used to have a house and cattle and now we've got no land where we can move to. This time we don't have any money to make another start, or to educate our children," she laments.

"We have nothing left, but we have to survive, so we've had to build our house from reeds."

The UK government is the biggest donor to Bangladesh, but its current annual aid package of £125m cannot hope to tackle the scale of the challenge now, let alone the problems that will come.

I understand that a review by Sir Nicholas Stern, commissioned by the UK's prime minister and chancellor to look at the economics of climate change, will conclude that rich nations need to do far more to adapt to the inevitable consequences of climate change.

It will also say developed countries must cut emissions immediately to minimise the effects.

Engineering solutions

Sir Nicholas' approach is criticised by some economists who argue that as climate change is beyond human control we should continue to maximise economic growth so we will be able to afford to pay for adaptation in the future.

In a recent article for the Spectator magazine, former chancellor Lord Lawson argued: "Far and away the most cost-effective policy for the world to adopt is to identify the most harmful consequences that may flow from global warming and, if they start to occur, to take action to counter them."

Lord Lawson suggests that a Dutch dyke-building engineer might solve the problems of Bangladesh.

The Stern review is likely to insist that both mitigation and adaptation are necessary, and will argue that economists have under-estimated the costs that climate change will impose and over-estimated the costs of cutting emissions.

The Dutch government itself rejects the optimistic view taken by Lord Lawson. A spokesman for the Dutch Embassy in Bangladesh told BBC News that it would be impossible to protect Bangladesh in the way Holland had been protected.

He said there were 230 rivers, which were much more dynamic than Holland's rivers, consistently undermining attempts to channel them through the sandy soil.

Mr Huq goes further: "It is ridiculous for people who know nothing about Bangladesh to make pronouncements on how much of it can or cannot be saved.

"Bangladesh is extremely vulnerable, and there is a major moral issue because this is not a problem that people here have caused," he said.

|

Home

Home Archives

Archives Home

Home Archives

Archives