Paradox of the Southasian Welfare State

by Gabriele Köhler, Himal, September, 2006

|

Southasian governments as a whole are already espousing a forward-looking state policy on welfare. The challenge now is to transform policy into action, while addressing the peculiar regional problem of social exclusion.

|

A common image of Southasia today is that of an eminently dynamic region – ‘driving’ the world economy via its high growth rates, its innovations and even, in a relatively new phenomenon, its outward foreign investment. India in particular features on the covers of magazines and scholarly research publications alike, leading with a GDP growth rate of 8-9 percent, pulling in resources from around the world, an electronic outsourcing haven of the developed economies. In the Maldives, which has succeeded in placing itself as a premier tourist destination, GPD per capita has reached USD 2500. Bangladesh is holding ground in its export boom of the past decade, despite the phase-out of the Agreement on Textiles and Clothing, which it A common image of Southasia today is that of an eminently dynamic region – ‘driving’ the world economy via its high growth rates, its innovations and even, in a relatively new phenomenon, its outward foreign investment. India in particular features on the covers of magazines and scholarly research publications alike, leading with a GDP growth rate of 8-9 percent, pulling in resources from around the world, an electronic outsourcing haven of the developed economies. In the Maldives, which has succeeded in placing itself as a premier tourist destination, GPD per capita has reached USD 2500. Bangladesh is holding ground in its export boom of the past decade, despite the phase-out of the Agreement on Textiles and Clothing, which it

had used creatively to enter global textile production chains.

Politically, too, Southasia can be seen as a vibrant region, in terms of its visions. The Southasian countries are strong supporters of the Millennium Declaration adopted in the United Nations General Assembly in 2000. The Millennium Development Goals – in which 191 state members of the UN have committed to achieving specific and time-bound results in education, health, HIV/Aids, gender equality and, most significantly, to improve the situation of women and children – now feature in the development plans of regional governments and are consistently used as a normative and policy point of reference by Southasian politicians.

The Southasia Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC) has a Social Charter committed to a people-centred framework for social development. Southasian governments have forward-looking constitutions. All are committed to free primary education as a public good, and the majority – Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Nepal and Sri Lanka – feature a commitment to free primary health services. Bangladesh, India, Nepal and Sri Lanka provide public early childhood development support services. In India, Nepal, Pakistan and Sri Lanka, governments offer free school meals, and the Indian Supreme Court decision to guarantee a midday meal to all schoolchildren in the country has been interpreted as a right to food for children – and is possibly unique in the world. Pakistan’s Constitution commits to provide food, clothing, housing, education and medical relief for citizens in need. These and other social policy elements suggest that Southasia is engaged in developing its own model of a ‘welfare state’.

The hybrid Southasian welfare state Much has been written and argued about welfare states, starting with the seminal work of Gosta Esping-Andersen (The Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism, Princeton, 1990). He and others have defined taxonomies of the role of government, looking into European, American and Southeast Asian types. Building on that early work, one can unfold a ‘cultural geography’ of the role of the state and social policy. Styles differ, depending on a country’s historically-shaped definitions of public goods, institutional and cultural history, and political programmes regarding the ‘appropriate’ role and size of government in the overall economy.

The European model of the welfare state is characterised by a broad range of publicly-provided goods – including all levels of education, some elements of health services, as well as economic infrastructure (free highways in some parts of Europe are a prime example) – combined with progressive taxation. The roots of this model lie in the agony and inequality of early industrialisation, which helped invent social democracy, added to the post-feudal, statist approach to industrialisation and notions of social justice embedded in Christianity and Judaism.

The neo-liberal, US-American approach on the other hand is characterised by a preference for the private provision of social goods accompanied by low taxation and high levels of voluntary philanthropy. This model is rooted in American history, where religious and economic refugees who had escaped authoritarian feudal regimes in Europe to arrive in early colonial America felt reticent about a strong state. It was their worries about a state that would again be imposing on citizens’ lives, the economy and social organisation that created a preference for self-reliance and group support, and took focus away from state involvement or responsibility. It is this notion of the role of government, and the penchant for a ‘small state’, that shaped the World Bank’s Washington Consensus of the 1980s, as well as its subsequent adaptations around the developing world.

When compared to the European and American models, the Southeast Asian model has been cast as a third variant, because of the strong role of government in guiding enterprises on the path to industrialisation and globalisation, coupled with the regulation of social services through compulsory insurance and pension schemes, and a politically strong state. Individuals and families are seen to take large responsibilities for social development, both in terms of work ethic and the high value placed on education, reinforcing the impact of public services offered by government. Philosophically,

this Southeast Asian variant is often described as ‘Confucian’.

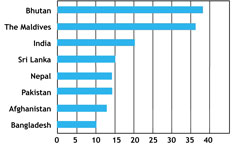

| TABLE 1 Central government revenue as % of GDP (2004) |

|

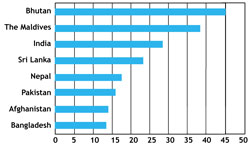

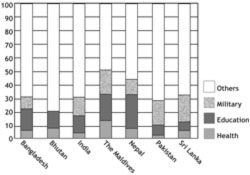

It is interesting to compare these – very simplified – European, American and Southeast Asian models with that found in Southasia, and to explore whether the role of government in the Subcontinent might offer a fourth type. A first pointer to this possibility is the extensive array of public goods that Southasian states provide, such as the commitment to free basic social services. A second pointer comes from selected fiscal indicators. Six countries in Southasia are devoting more than 30 percent of government expenditure to health and education – certainly suggesting a welfare state approach (see Table 3). Moreover, in four countries – Bhutan, the Maldives, India and Sri Lanka – the share of government expenditure in GDP runs between 20-45 percent, and the share of government revenue to GDP lies between 15-35 percent (see Tables 1 and 2).

Sources of this welfare-state ‘culture’ in Southasia are multilayered. Postcolonial states like India and Sri Lanka were steeped in a notion of rights, entitlements and social justice, drawing on the Independence movement, as well as influences in Soviet socialism and British Fabianism – both introduced by elites trained in Oxford and Cambridge. Sri Lanka was actually one of the earliest welfare states, introducing universal education and primary health care services in the 1940s. It has also been argued that Buddhism and Islam, with their principles of altruism and social responsibility – such as the zakat system, by which a certain percentage of an individual’s earnings are given to the poor – have contributed to shaping Southasian welfarism. These factors suggest something of a hybrid welfare-state model: there is a strong commitment on the part of government to social policy, but in contrast to the tax-reliant European model and in tune with the lower levels of GDP, a larger share of the funding for social goods comes from loans and grants.

Undermined by social exclusion

The Southasian welfare state, then, could be expected to contribute to excellent outcomes in social policies that would positively and directly impact human development. Anyone who knows Southasia will, however, immediately interject: the Southasian welfare-state model, hybrid or not, has had a disappointing performance in terms of implementation, as any social indicators will show (see box). Is this due to slipshod delivery, or to systematic corruption and misappropriation of the welfare-state budgets? Is it due to internal and external policy pressure to downsize the state, and privatise and commercialise social services? What is the root cause of this ‘Asian paradox’ – good macroeconomic performance coupled with political will and commitment to mass welfare, coexisting with abject poverty, income disparity and under-performance in terms of health and education? This paradox can only be understood when one looks at the pervasive phenomenon of social exclusion.

Southasia remains a region struggling with manifold layers of social exclusion, defined as systematic or de facto processes of denial of access to entitlements, based on caste, clan, tribe, ethnicity, language and religion, factors that are often bundled with location.* Exclusion is experienced at all levels of society, at the community, inter- and intra-personal levels; it is also deeply entrenched – as some say, for the past three millennia. In Southasia, gender disparities and income poverty cut across all the exclusionary factors and deepen social exclusion. In most of Southasia’s social indicators on health and education, there are wide differences between boys and girls, and between the dominant population and those who are marginalised. One telling statistic: the life expectancy of a member of the Dalit caste in Nepal is a full 20 years less than the national average, 40 instead of 60 years.

| TABLE 2 Central government expenditure as % of GDP (2004) |

|

How does social exclusion work? In health or education, professionals treat children differently depending on their social background. In some schools, Dalit children are made to sit separately or stand at the back of the classroom; they tend to be verbally abused, beaten or ridiculed with impunity more frequently than other children. Teachers miss school as they do not find it worth their effort to make their way to excluded communities. Some doctors are reluctant to touch low-caste patients, whom they consider to be polluting. Cooperatives refuse to buy milk from cows owned by Dalits. Village water points are segregated, and Dalit women cannot collect water at the ‘upper-caste’ end of the village. Ethnic or tribal groups living in concentrated regions are provided only sporadic services. Some exclusion is also internalised. ‘Low-caste’ women are taught by their mothers not to wear colourful clothes, nor to expect elaborate wedding ceremonies, as this would not be ‘proper’. Dalit children do not enter the homes of Brahmans, and Dalit youth are hesitant to apply for employment in non-traditional occupations.

These exclusionary practices are not limited to caste societies. In other parts of Southasia, systems such as the biraderi, or old traditions in tribal communities, have similar effects. The paternal-side matriarchs in a household will often not allow their daughters-in-law to seek medical attention while pregnant or in childbirth – they did not have that luxury themselves, and it would take household resources from other purposes. All of these factors amplify gender-based exclusion and discrimination; they are doubly strong in their impact on children of excluded communities, as well as for girl children, who experience discrimination not just extraneously in ‘society’ but also within their own family and immediate community, and who thus experience social exclusion in a compounded, oppressing manner.

Social exclusion undermines the Southasian ‘welfare state’ and its many social policy measures, and it does so on many levels. Addressing social exclusion therefore requires bold, as well as extensive, policy measures. It requires sufficient public resources to ensure the effectiveness of policies designed to enable social inclusion. It requires ensuring a connection between implementation of policies and legislation, and the fundraising and delivery capacity of central and state- or district-level bodies. It necessitates empowering the socially excluded directly or through civil society organisations, who could genuinely voice their interest. Finally, it requires measures to counter the visible and invisible processes through which elites weaken government decisions to address social exclusion – which in principle is banned in all of Southasia’s constitutions – for example, by obstructing delivery or obscuring information on entitlements.

A call for transformative social policy

How then can social exclusion be addressed? Southasia itself is a laboratory of possible answers, offering a host of promising elements. They include political instruments such as reservations, quotas and other forms of political affirmative action. The recently reinstated House of Representatives in Nepal adopted several landmark decisions, one of which is a declaration of intent to reserve 33 percent of all government posts for women. In India, reservations for the ‘ scheduled tribes and castes’ are part of the 1948 Constitution, and have seen periodic and heavily contested amendments throughout the course of India’s history. The most recent decision to extend reservations for Other Backward Classes to central educational institutions, leading to a level of controversy, is a reminder of the commitments of the Indian state.

| TABLE 3 Public expenditure on health, education and defense as % of total public expenditure |

|

An interesting example comes from Bangladesh, where a large-scale government initiative was introduced to overcome persistent gender disparities in schools: every girl in secondary school is entitled to a government stipend designed to enable her to complete secondary education. Objectives include ensuring that the gap in girls’ educations be closed, and delaying marriage. The scholarship is paid directly to the girl student, and continues as long as she passes her exams, attends at least 80 percent of school days, and does not become pregnant. Over time, this enlarged cadre of trained young women can become the women doctors and teachers needed to help the next generation of children go to school, in a country where girls are meant to be taught by women teachers. This special measure has helped Bangladesh reach gender parity in education. On a smaller scale,

with a similar intent of overcoming social exclusion, Nepal has a stipend for Dalit children to cover the transaction costs of schooling, and serve as an incentive.

There is similar potential in India’s National Rural Employment Guarantee Act, adopted in 2005. Every rural household is entitled to 100 days of paid work per year – as a measure conceived to tackle rural poverty and distress migration. The work offered is basic labour on public works schemes, and would be attractive as a source of income to only the poorest of the poor. But it is an attempt to transform rural communities who are systematically excluded from learning and health by virtue of their extreme economic poverty. Its additional objective is to improve the accessibility and productivity levels of villages that would have positive externalities and virtuous multiplier effects, as more households in villages could buy basic provisions.

One welcome micro-initiative in Uttar Pradesh deserves mention too, as a special effort in the transformative sense, and would require policy decisions if it were scaled up to cover the entire country. One district in UP introduced low, blue-coloured tables in the hitherto furniture-less classrooms. The primary objective was to give children a writing surface and improve their posture and attentiveness. What it seems to be doing in effect, however, is to begin to change the entire dynamics in the classroom. Children feel acknowledged and respected, they literally have a place at the table, and this table is multi-caste; during classroom hours at least, there is a level of social equality. School is becoming enjoyable – for children and hence also for teachers.

Transformative social policy also needs to encompass fiscal budget principles. In India, the government monitors its expenditures for child-friendliness, combing through all budget lines to compile data on expenditure that relates to children. In Nepal, the ‘20/20 initiative’, first introduced at the World Social Summit in Copenhagen, informs an effort by the Planning Commission to ensure that 20 percent of government expenditure is devoted to basic social services.

On the revenue side, India, Nepal and Pakistan have introduced special taxes – a cess – for education; in Sri Lanka, a cess finances the National Plan of Action for Children. India’s cess, added to the value-added tax, is devoted to education, and has within one year quadrupled the amount of budget available at the national level for education. Other ideas are to introduce dedicated taxes to fund primary health services.

All this is not sufficient, however. Universalism and social inclusion cannot happen without participation. Questions of ‘voice’ and empowerment need to become integral. First, participation is a right. Second, if users co-design social services, the related interventions are far more likely to truly meet needs and expectations. Third, users need to be able to assess and evaluate services, and ideally to have alternative choices. From a welfare state discussion, then, this would suggest several decisive factors for policy choices: consultations to generate inclusive, equitable and transformative policies, and interventions geared to overcoming social exclusion and ensuring every citizen’s access to high-quality social services. This could conceivably entail forms of participation built into the processes, notably regarding ‘delivery’.

Here too, one can discern an emerging model in Southasia. Without explicit reference to Gandhian notions of village democracy, several Southasian countries have introduced into social policymaking a considerable degree of decentralisation, transferring budget resources and decision-making authority to district levels. The intended outcome is better service delivery; since users determine priorities there is higher transparency, and local authorities and service-providers – teachers, health professionals – are directly accountable to their fellow residents (and voters) in each community.

Decentralisation could be seen as more than just a form of delivery, but rather as a school of policy on its own. Obviously, this can only function to the extent that socially excluded groups and individuals – women, members of the so-called low castes, tribals, young people – are enabled and empowered to speak and decide. Thus, decentralisation mechanisms need to be aware of and sensitive to processes of exclusionary participation, where consultations and participation are only token, because the disenfranchised do not have the means, the time or the confidence to shape decisions. Again, measures introduced by governments – such as quotas for women in community decision-making groups – can provide support, normatively and practically, to gradually ensure genuine inclusion. This is where special measures come in, and can over time have an empowering impact.

One might then posit that a Southasian model of the welfare state is emerging – hybrid in the way it funds social services, but potentially transformative in nature. It is a combination of the European model’s principle to provide social goods universally, combined with three new strands. It is guided by an explicitly rights-based approach that transcends the top-down tendency observed in conventional welfare states by integrating genuine participation into decision making. It reinforces the principle of universal coverage with special efforts to address social exclusion, so that the disadvantaged can access quality services. It incorporates moves to change attitudes and behaviours. This model could give new meaning to the notion of Asian drivers.

Southasia – a Subcontinent of children

More than a half-billion children – 584 million, to be precise – live in Southasia, the largest child and youth population in any region. Southasia’s young make up one quarter of the world’s children. Almost every second person here is under 18, with the exception of Sri Lanka and India, where they make up 30 and 40 percent of the population respectively.

The youthfulness of the Subcontinent’s population is a gift, but it is also a daunting responsibility. And indeed, most of the region’s countries are unlikely to meet the targets they have set for themselves to substantially improve the situation of children by 2015. Poverty and deprivation affects as many as 330 million children here. Child malnutrition stunts the growth of every second child. 67 out of 1000 children die before they turn one; another 92 out of 1000 succumb before they turn five. Maternal mortality levels are at the highest level in global comparison, with 560 in every 100,000 births resulting in the mother’s death. In education, primary school enrolment is at 74 percent. As a result of decades of poor or unavailable schooling, in India only half of adult women can read; in Nepal, one-in-three; in Afghanistan, one-in-five.

The dire situation of Southasia’s children – the most vulnerable group in any society, but even more palpably at risk in situations of gender discrimination and social exclusion – is perhaps the strongest normative underpinning for a genuinely transformative social policy. Credit is due to the governments in Southasia, who have recognised this in their many decisions on education, health, school meals. If the aspirations can be translated into unfettered action, this would serve to drastically and effectively change the situation of a half-billion children in Southasia – building on and building up a Southasian model of the welfare state, and altering the lives of millions of families.

*See for example the works of Janet Gardener and Ramya Subrahmanian, “Tackling Social Exclusion in Health and Education in Asia”, DFID, Delhi, 2006; Emma Hooper and Agha Imran Hamid, “Scoping Study on Social Exclusion in Pakistan”. Islamabad, 2003; Lynn Bennett, “Unequal Citizens: Gender, Caste and Ethnic Exclusion in Nepal”, World Bank/DFID, Kathmandu, 2006; Annie Namala, “Children and Caste-based Discrimination: Policy Concerns”, UNICEF ROSA, Kathmandu, 2006.

|

Home

Home Archives

Archives Home

Home Archives

Archives