Demerger: Lessons for the Future

by Satheesan Kumaran, Tamil Guardian, November 1, 2006

|

The Supreme Court ruling demonstrates the fragility of constitutional changes, even when underwritten by powerful international actors such as India.

|

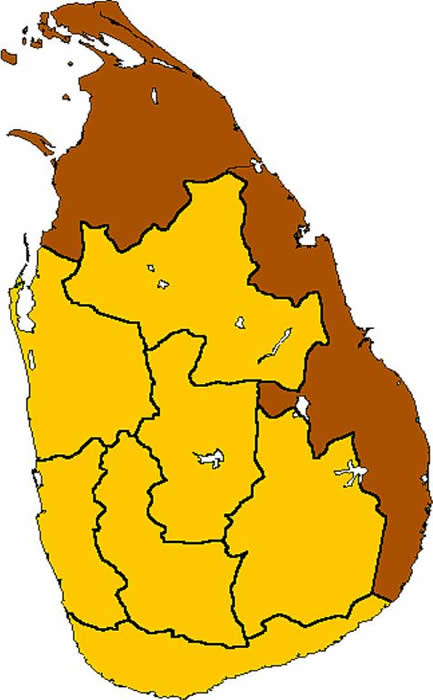

The ruling by Sri Lanka Supreme Court on October 16, 2006 that the merger of the Northern and Eastern provinces into a single entity was unconstitutional, invalid, and illegal was intended as a body-blow to the Tamils claim for a homeland. The ruling by Sri Lanka Supreme Court on October 16, 2006 that the merger of the Northern and Eastern provinces into a single entity was unconstitutional, invalid, and illegal was intended as a body-blow to the Tamils claim for a homeland.

The ruling serves to reinforce the Tamils’ conviction that they cannot expect justice from the highly politicized and Sinhala-dominated Sri Lankan judiciary. That conviction derives from the judiciary’s history of ruling against the interests of Tamils ever since the island was granted independence from Britain in 1948. Notably, all the judges on the panel which ruled against the merger were Sinhalese.

The merger came out of the Indo-Sri Lanka Accord signed on 29 July 1987 by the then Indian Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi and the then Sri Lankan President JR Jayawardene.

Paragraph 1.4 of the Agreement states: “the Northern and the Eastern provinces have been areas of historical habitation of Sri Lankan Tamil speaking peoples, who have at all times hitherto lived together in this territory with other ethnic groups.”

The acknowledgement that the Northern and Eastern provinces are the historical habitation of Tamil speaking people was well received by Sri Lanka’s Tamils and Muslims.

The Accord stated that a referendum must be held by end of 1988 in the eastern province to enable the people there to decide whether they wanted to remain merged with the Northern province.

Unfortunately, the referendum did not take place because the war that erupted between the Indian armed forces and LTTE in late 1987 continued for three years. Eventually, the Indian armed forces were expelled from Northeast in 1990. The merged entity continues to exist on account of a number of presidential orders that repeatedly extended the period for a referendum.

A cunning politician, Sri Lankan President Jayawardene signed the pact primarily to co-opt India into destroying the LTTE for him. He was opposed to the merger of the Northern and Eastern provinces as a single entity but agreed to it as a tactic.

His real motives were brought starkly to light in a statement he made to the National Executive Committee of his party, the United National Party, just a few days before signing the Indo-Lanka Accord.

“Only one thing has to be considered. That is a temporary merger of the North and East,” he declared.

“A referendum will be held before the end of next year on a date to be decided by the President to allow the people of the East to decide whether they are in favour or not of this merger.”

“The decision will be by a simple majority vote... In the Eastern Province with Amparai included there are 33% Muslims, 27% Sinhalese and the balance 40% Tamils,” he said.

“Then if the referendum is held by the Central government and the approval of those who return to the East is sought, I think a majority will oppose it. Then the merger will be over.”

“What do we gain by this temporary merger?” the President asked before answering: “It would see the end of the terrorist movement.” From the outset, therefore, the merger of the Northeastern province was intended as a temporary one to overcome the difficult time faced by Jayawardene’s government.

The President himself was facing political turmoil in Colombo. Jayawardene confirmed, at a press conference immediately after the signing the Indo-Lanka Accord, that, at the polls in the Eastern Province, he would campaign against the merger.

Moreover, even on the issue of the merger, the Tamils cannot have a collective say. One must seriously wonder why the people of the Northern province were not entitled to participate in a referendum determining whether they remain merged with the people of the Eastern province.

The ruling of the Sri Lanka Supreme Court is a serious diplomatic and political challenge to India, which after all, had underwritten the Northern and Eastern provinces as the traditional habitation of the Tamil people. It remains to be seen what, if anything, India intends to do now. For decades, the international community has ignored the relentless dismantling of the Tamils’ claim to their homeland. Successive Sri Lankan governments since 1948 have systematically colonized the Northeast, especially the East, with Sinhalese settlers.

Coloniosation is still going on in the Eastern province. State land has been distributed to Sinhala people and to families of members of the armed forces. These Sinhala colonizers are given weapons ostensibly to protect themselves from LTTE, but in reality to ensure the gradual encroachment of Tamil territory cannot be checked. After 18 years of the merger, the ultra-nationalist JVP, an ally of the ruling SLFP filed three Fundamental Rights applications. The Bench of five Supreme Court Judges, on October 16, 2006, held that the Proclamation merging the North and East provinces as one entity had no force in law.

The Bench ruled: "the Proclamation made by the then President declaring that the Northern and Eastern provinces shall form one administrative unit has been made when neither of the conditions … as to the surrender of weapons [by the Tamil militants] and the cessation of hostilities, were satisfied.”

“Therefore, the order must necessarily be declared invalid since it infringes the limits which Parliament itself had ordered.” Notably, the Supreme Court refused to hear the petitions filed by challengers, both Tamils and Sinhalese, to the JVP’s petition.

The JVP petitioners stated that their right to equality had been violated by the failure of the President to set a date for the establishment of a separate Provincial Council for the Eastern Province. They also protested what they said was a consequential failure to afford the petitioners, as well as other inhabitants, an opportunity to exercise their right to vote at an election for membership of such council.

What this episode demonstrates is the fragility of constitutional changes, even when underwritten by powerful international actors such as India.

Those advocating changes to the Sri Lankan constitution as a remedy for the deep-seated ethnic divide in the island are oblivious to these realities.

Only the establishment of a constitutional arrangement which cannot be dismantled by a Sinhala-dominated political center or which is not subject to the Sinhala-dominated judiciary can constitute a lasting solution. Anything else would be a new ethnic conflict awaiting a trigger.

|

Home

Home Archives

Archives Home

Home Archives

Archives