Two Sri Lankan Army Commanders during the IPKF period (1987-1990)

Ilankai Tamil Sangam

Association of Tamils of Sri Lanka in the USA

Published by Sangam.org

by Sachi Sri Kantha, March 23, 2012

|

As for the LTTE, the Mahattaya betrayal was covered by Adele Balasingham in her The Will to Freedom (2001) book. Colonel Karuna’s betrayal had been covered by me in my Pirabhakaran Phenomenon (2005) book, and in many opinion pieces in this website. Kumaran Pathmanathan’s betrayal waits for more expose. |

Two Sri Lankan Army Commanders during the IPKF period (1987-1990)

|

| Lieutenant General Nalin Seneviratne [1985 Feb.12 to 1988 Aug.15] |

|

| Lieutenant General Hamilton Wanasinghe [1988 Aug.16 to 1991 Nov.15] |

The bombastic Sri Lankan Army

If there is an Olympic medal for bombast and vanity, men from Sri Lankan army would win it hands down, every four years. During LTTE-Indian army confrontation period (October 1987 to March 1990), Sri Lanka had two army chiefs. They were Nalin Seneviratne (1931-2009) and Hamilton Wanasinghe (b. 1933). I checked the Wikipedia entry for Sri Lanka’s ex-army chief Nalin Seneviratne [accessed on March 21, 2012]. About his achievements in the Sri Lankan army, the biodata states,

“On February 11, 1985 he was appointed as the 10th Commander of the Sri Lanka Army and promoted to the rank of Major General. The following year he was promoted to Lieutenant General. Commanding the army for over three years he oversaw the largest military operation undertaken to that date, the Vadamarachchi Operation and carried out a rapid expansion of the army. He retired on August 16, 1988. He had been awarded the Vishista Seva Vibhushanaya (VSV) for over 25 years of distinguished service in the army, his other medals include the Purna Bhumi Padakkama, Vadamarachchi Operation Medal, Sri Lanka Armed Services Long Service Medal, Ceylon Armed Services Long Service Medal, Republic of Sri Lanka Armed Services Medal and the President's Inauguration Medal.”

With their penchant for puffing up the deeds in battlefields, numerous ‘medals’ were concocted for significant (or more properly, insignificant) battles, by the Sri Lankan military. Quite a number of ‘medals’ carried the tags of place names of the North-East regions of the island. Vadamarachchi Operation Medal was one of these. The medals and badges in the official photos of Sri Lanka’s army commanders remind me of a Cheney cartoon of a general’s vanity parade that appeared in the New Yorker (Aug.17, 1987). I couldn’t locate a specific entry for Hamilton Wanasinghe biography in the wikipedia [accessed on March 21, 2012], probably because he is black-listed by the current political hierarchy, as he supported the current President’s opponent General Sarath Fonseka in the 2010 presidential election. A cynic would quip that the best medal that should adorn the uniform of Seneviratne and Wanasinghe would be a wimp medal during 1987-1990 for not engaging the Indian army, which landed in Sri Lanka after the Rajiv Gandhi- Jayewardene Accord.

An Army full of Wimps

Now, let me provide some evidence on what the Sri Lankan army did, when LTTE was tackling the Indian army during 1987-1990. In June-July 1989, there arose an occasion that the then commander-in chief President R. Premadasa was locking horns with the then Indian prime minister Rajiv Gandhi about requesting immediate withdrawal of the Indian army from the island. Naively, he even believed that the Sri Lankan army generals (if  called for combat) would affirmatively answer his call. But, this didn’t happen in reality, because Sri Lankan army was full of wimps. I provide scans from two international newsmagazines nearby, and offer excerpts [indicated in red boxes]:

called for combat) would affirmatively answer his call. But, this didn’t happen in reality, because Sri Lankan army was full of wimps. I provide scans from two international newsmagazines nearby, and offer excerpts [indicated in red boxes]:

“The president, as commander-in-chief of the Sri Lankan army, was apparently prepared to order his soldiers to confront any Indians still in the country after July 29th who had not confined themselves to barracks. A small-scale fight would win him Sinhalese support, and internationalsympathy for a small nation being bullied by a bigger neighbor. No way, said his army commanders; they vetoed any confrontation, limited or otherwise. Fifteen thousand ill-equipped Sri Lankan soldiers in the north-east were clearly unable to eject an Indian force three times their size. Sri Lankan officers were told by their commanders to invite their Indian counterparts into their camps for tea and a friendly chat.” [Colombo correspondent, Economist, August 5, 1989, p. 33]

“India and Sri Lanka edged perilously close to military confrontation last week. Sri Lankan agitators called for boycotts of Indian goods and bombed Indian banks and other establishments. Security troops moved in to set up roadblocks and enforced a nationwide curfew. Indian diplomats relocated to a well-guarded hotel and sent their families home. Meanwhile India positioned an aircraft carrier just 30 miles from the Sri Lankan coast, ready to fly in commando helicopters the instant diplomats’ lives were endangered. In the end it didn’t come to that. One day before Sri Lanka’s deadline for withdrawing all 45,000 Indian troops stationed in the country, the two sides agreed on a compromise: a token Indian troop pullout immediately, followed by negotiations on a complete withdrawal. That was enough to ease the crisis, but only for the moment.” [Susan Greenberg and Sudip Mazumdar, Newsweek, August 7, 1989, p.9]

The details presented in these two news items identify the Sri Lankan army wimps lucidly. Prabhakaran and his associate military leaders, in leading LTTE, against the officially stated “45,000 Indian troops” were never daunted by the might of his adversary. They carried on their struggle valiantly, and eventually turned tables against their adversaries. I guess that the anonymous ‘Colombo correspondent’ for the Economist magazine could have been Mervyn de Silva. Among all the Sinhalese journalists, he was an exception in evaluating the strength of Prabhakaran’s leadership on its terms, without racist bias.

Isn’t it humorous that the Sri Lankan military generals who prided themselves with Vadamarachchi Operation Medal in 1987, had a serious bout of ‘thigh-shaking’ fever in 1989, when their Commander in Chief called them for offensive action against the Indian army?

Comparison between Mandela and Prabhakaran: My own table

In part 6, I provided my own table comparing MK and LTTE. Here, I provide my table with 18 criteria comparing the lives of Nelson Mandela and Velupillai Prabhakaran. The details in it are accurate, to the best of my ability. The sources from which I made this table are provided at the end of this part. Though an age difference of 36 years exists, please note the similarities between Mandela and Prabhakaran in personal habits and personality.

Betrayers of MK and LTTE

Betrayers had been a bane to secret networks in history. One could begin with Judas Iscariot, the 12th apostle who betrayed Jesus Christ. Incidentally, the March 2012 issue of National Geographic’s cover feature was on the Christian Apostles. Even Uncle Sam’s secret network CIA routinely suffer from betrayal, (the latest being that of Aldrich Ames) in their mission.

I have identified two betrayers for MK and three betrayers for LTTE (see Table). Of the two betrayers for MK, Mandela makes mention of Bruno Mtolo, in his autobiography. I reproduce the 6 paragraphs on this episode, relating to his Rivonia treason trial. Percy Yutar (1911-2002), mentioned was the prosecuting deputy attorney general for South African apartheid regime.

“The state’s star witness was Bruno Mtolo, or ‘Mr.X’ as he was known in court. In introducing ‘Mr.X’, Yutar informed the court that the interrogation would take three days and then, in theatrical tones, he added the witness was ‘in mortal danger’. Yutar asked that the evidence be given in camera, but that the press be included provided that they not identify the witness.

Mtolo was a tall, well-built man with an excellent memory. A Zulu from Durban, he had become the leader of the Natal region of MK. He was an experienced saboteur, and had been to Rivonia. I had met him only once, when I addressed his group of MK cadres in Natal after my return from the continent. His evidence concerning me in particular made me realize that the state would certainly be able to convict me.

He began by saying that he was an MK saboteur who had blown up a municipal office, a power pylon, and an electricity line. With impressive precision, he explained the operation of bombs, land mines, and grenades, and how MK worked from underground. Mtolo said that while he had never lost faith in the ideals of the ANC, he did lose faith in the organization when he realized that it and MK were instruments of the Communist Party.

His testimony was given with simplicity and what seemed like candor, but Mtolo had gone out of his way to embellish his evidence. This was undoubtedly done on police instructions. He told the court that during my remarks to the Natal Regional Command I had stated that all MK cadres ought to be good Communists but not to disclose their views publicly. In fact, I never said anything of the sort, but his testimony was meant to link me and MK to the Communist Party. His memory appeared so precise the ordinary person would assume that it was accurate in all instances. But this was not so.

I was bewildered by Mtolo’s betrayal. I never ruled out the possibility of even senior ANC men breaking down under police torture. But by all accounts, Mtolo was never touched. On the stand, he went out of his way to implicate people who were not even mentioned in the case. It is possible, I know, to have a change of heart, but to betray so many others, many of whom were quite innocent, seemed to me inexcusable.

During cross-examination we learned that Mtolo had been a petty criminal before joining MK and had been imprisoned three previous times for theft. But despite these revelations, he was an extremely damaging witness, for the judge found him reliable and believable, and his testimony incriminated nearly all of us.” [Long Walk to Freedom, pp. 357-358]

Mandela’s biographer Martin Meredith, includes Patrick Mthembu (a founding MK member), in addition to Bruno Mtolo. He was killed by MK operatives in 1978 for his betrayal, according to his son Diliza Mthembu. Martin Meredith’s descriptions about these two betrayers are reproduced below:

“The state’s key witness [during the Rivonia treason trial] was Bruno Mtolo, a member of MK’s Natal regional command, an active saboteur for three years whom Mandela had met on his journey to Durban in August 1962 and who had also visited the Rivonia headquarters in 1963, where he had held discussions with Sisulu and Mbeki. Arrested by the security police in August 1963, Mtolo had decided within hours to defect, claiming he had become disillusioned with MK’s leadership and with the extent of communist influence over the ANC, even though he himself was a Communist Party member. Mtolo implicated not only Mandela, Sisulu and Mbeki but a host of other people in MK activities.

“Another key witness was Patrick Mthembu, a member of the Johannesburg regional command, who had trained in China and had worked closely with all the conspirators, both during the days when the ANC was a legal organization and during Umkhonto operations. Mthembu had spent two periods in solitary confinement. He was offered indemnity against prosecution in exchange for his testimony.” [Nelson Mandela, pp. 259-260].

As for LTTE, Mahattaya betrayal was covered by Adele Balasingham in her The Will to Freedom (2001) book. Colonel Karuna’s betrayal had been covered by me in my Pirabhakaran Phenomenon (2005) book, and in many opinion pieces in this website. Kumaran Pathmanathan’s betrayal waits for more expose.

International Recognition by the Establishment

International Recognition by the Establishment

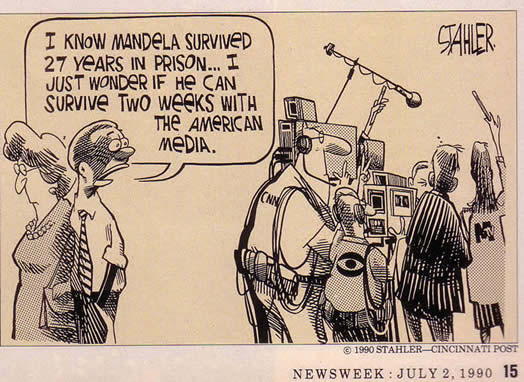

In 1977, after listening to the readings of works by political prisoners, American humorist Art Buchwald jabbed in his inimitable style: “In this country, when you attack the Establishment, they don’t put you in jail or a mental institution. They do something worse. They make you a member of the Establishment.” [Time, Dec.5, 1977, p. 20] At that time, Mandela was in jail. The Cincinnati Post’s editorial cartoonist Stahler’s 1990 cartoon when Mandela visited the USA depicts the same sentiment partially. What Buchwald was probably commenting relates to Martin Luther King Jr., who was made a distinguished member of the Establishment and decorated with the Nobel Peace Prize in 1964. The same fate did repeat to Nelson Mandela too, when he too was decorated with the Nobel Peace Prize in 1993, at the age of 75 years.

For various reasons, Prabhakaran missed out on this Establishment prize. Compared to Mandela, Prabhakaran probably was too young. The near thing, Prabhakaran received as a sort of International recognition, was being anointed as one of the 100 Most Influential Asians of the Century by the Time magazine. [August 23-30, 1999]. Of course, Prabhakaran did not make to the top 20 primary selections (19 men and one woman). But, Prabhkaran was included in the next rung of 80 secondary selections, in the category of insurgents, “who fought their own governments for causes ranging from communism to freedom”. Prabhakaran was only 45 then. The primary selection for this category was Vietnam’s independence leader Ho Chi Minh (1890-1969). Even among the five secondary selections in which Prabhakaran was included, two were composites (Japanese soldiers who revolted in 1936, and the Afghanistan’s mujahedin guerrillas who defeated the Soviet army).

Sources Consulted

Adele Balasingham: The Will to Freedom. Fairmax Publishing, Mitcham, UK, 2001.

Martin Meredith: Nelson Mandela – a biography. Penguin Books, London, 1997.

Nelson Mandela: Long Walk to Freedom –the autobiography of Nelson Mandela. Little Brown and Co, Boston, 1994.

Sachi Sri Kantha: Pirabhakaran Phenomenon, Lively Comet Imprint, Japan, 2005.

V. Visvanatha Pillai: A Dictionary – Tamil and English, 6th edition, 1951, Madras, p.514 (for the meaning of Prabhakaran name).

*****

© 1996-2025 Ilankai Tamil Sangam, USA, Inc.