SANGAM.ORG

Ilankai Tamil Sangam, USA, Inc.

Association of Tamils of Sri Lanka in the USA

Comparing Notes on Collaborators and Informers

How have other cultures treated these nasty deviants?

by Sachi Sri Kantha

|

“Dear Sir,

Mr Anandasangaree was nominated by the authorities of his country, the Sri Lanka National Commission for UNESCO. The number of nominations is confidential…

|

Collaborators and Informers

The words ‘collaborator’ and ‘informer’ have a nasty taste to them. Both words are used alternatingly, since the deeds performed by collaborators and informers occasionally overlap. In my evaluation, there is a subtle distinction between ‘collaborator’ and ‘informer’. Collaborators for the most part have to function openly, since they operate in the realm of politics, and politicians crave publicity. Contrastingly, informers dwell in secrecy since they mostly focus on the realm of extra-political activity (especially military details and spying). However, the boundary is porous, as one can see from the deeds of embedded para-military functionaries like Douglas Devananda, D.Siddharthan and V.Muralitharan aka Karuna. An informer like Karuna, who was expelled from the LTTE, is now yearning to transform himself into a politician (and collaborator) and thus is presenting routine interviews to media hacks (via telephone and email) without physically appearing above ground.

Every liberation movement (the American revolutionary war of the 1770s, the French revolutionary war of the 1790s, the Chinese Communist revolution of the 1930s and 1940s, the Cuban revolution of the 1950s and the Vietnam war of the 1960-70s) has spawned collaborators and informers. If one reads history, Fate has never been kind to such nasty deviants who, for convoluted reasons, consorted with the enemies of their clan/tribe/ethnic group/religion.

Every liberation movement (the American revolutionary war of the 1770s, the French revolutionary war of the 1790s, the Chinese Communist revolution of the 1930s and 1940s, the Cuban revolution of the 1950s and the Vietnam war of the 1960-70s) has spawned collaborators and informers. If one reads history, Fate has never been kind to such nasty deviants who, for convoluted reasons, consorted with the enemies of their clan/tribe/ethnic group/religion.

Despite such lessons of history, collaborators and informers do show up without fail, and Eelam Tamils know this well, too. We have had our share of sourpusses and sourgrapes who can be pushed into the columns of collaborators and informers. Just check for a while. Every decade since the 1970s has had its prominent Tamil collaborators; the Kumarasuriyars and Duraiappahs (in the 1970s), Rajadurais and Varadaraja Perumals (in the 1980s), Kadirgamars and Devanandas (in the 1990s and 2000s) and, Anandasangaris and Karunas (in the 2000s).

An in-depth sociological study on the character traits of finks among Eelam Tamils has yet to be carried out. I list some identifiable categories among the Tamil collaborators and informers.

Categories

(1) Few are legitimate players on the stage of Eelam Tamil nationalism for a noticeable duration, who later deserted the nationalist ranks for reasons of vanity and some specific character flaws (C. Rajadurai and Karuna).

(2) Few are political chameleons, who change their skin color for self-protection and promote themselves as an ‘Alternate Tamil leadership’ in the government’s media mouthpieces (Devananda and Anandasangaree).

(3) Few are ‘Johnny Come Latelys’ to politics from other professions, who became intoxicated by the ‘token Tamil’ Cabinet minister rank offered by the SLFP top dogs (Kumarasuriyar and Kadirgamar).

(4) A couple are eccentric loners with considerable ego, whose chief focus was access to the Sinhalese party (UNP or SLFP) leader (Duraiappah of ‘Duraiappah Stadium’ fame and Devanayagam).

(5) A couple are high profile political/societal brokers who also boasted of some academic clout (Neelan Tiruchelvam and Rajan Hoole).

Anandasangaree’s Nominator for the Weasel Diplomacy Prize

How the Colombo’s media mouthpieces of the Sri Lankan Government try their best to project these collaborators and informers as messiahs of Eelam Tamils is indeed worth a post-graduate dissertation, for any young aspirant. Last month, septugenarian Veerasingham Anandasangari was honored in Paris with the 2006 UNESCO-Madanjeet Singh prize. For quite a percent of Eelam Tamils, this so-called 'humanitarian award' to a chameleon politician who isn’t known for any creative output whatsoever for the benefit of his people, and who hasn’t authored a single book in any language (including his own mother tongue Tamil!) on any theme of societal interest, was a supreme puzzle.

I thought of finding out who nominated Anandasangaree for this award, to trace the credentials of the the nominator and whether this nominator is an entity with a reputation for integrity and academic credibility to evaluate the selection criterion for the prize, i.e., “promotion of tolerance and non-violence”. I sent an e-mail to the UNESCO’s officer in charge of this particular UNESCO-Madanjeet Singh prize. The response I received promptly from Mr.Serguei Lazarev on November 22nd, didn’t surprise me. To quote,

“Dear Sir,

Mr Anandasangaree was nominated by the authorities of his country, the Sri Lanka National Commission for UNESCO. The number of nominations is confidential….”

There you have it, in black and white. Though not stated clearly, the phrase “authorities of his country” in all probablities implies the authorities of the “political kind”. The nominator of Anandasangaree, the “Sri Lanka National Commission for UNESCO”, is an appendage of the Sri Lankan Ministry of Education. Its current office holders are as follows:

Chairman: Mr Susil Premajayantha

Vice-Chairman: Mr Ariyaratne Hewage

Secretary-General: Mr R.P. Perera

Deputy Secretary-general: Mr Prasanna Chandith

The Chairman, Susil Premajayantha (born 1955), is merely the Minister of Education in President Mahinda Rajapakse’s Cabinet. And it’s a no-brainer to deduce that the Sri Lankan President’s coterie, for purely political reasons, nominated Anandasangaree for this award, to felicitate his “services as a collaborator.”

Anandasangari’s acceptance speech, delivered on November 16th, for his purported contribution to “promote tolerance and nonviolence” was a good example of the cowardice and servility of a Tamil collaborator, to please his nominators and sponsors of this ‘Weasel Diplomacy’ prize. A more detailed analysis on whether Anandasangari merits such an “international” award is under preparation.

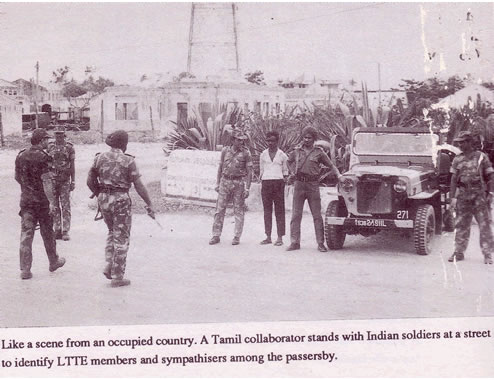

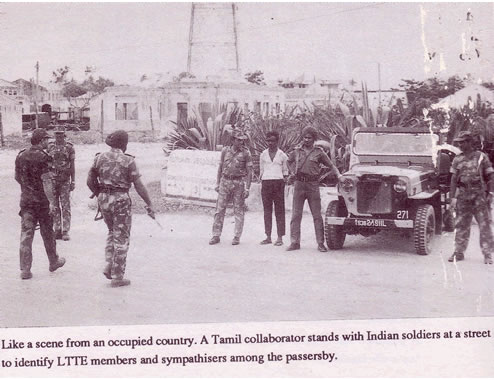

~1987 ~1987

|

Do you think that how the LTTE has tackled some Tamil collaborators and informers in the past has been distorted by the media hacks of the Sri Lankan government, culture-challenged diplomats (especially the likes of American ambassadors who are stationed in Colombo) and journalists (the South Asian correspondents of American print media, such as The New York Times and Time magazine, and the Sri Lankan government's mouthpiece mass media)? There’s no doubt on this delicate issue.

The four articles/commentaries/newsreports presented below, describing the thinking on the collaborators and informers among Americans, Palestinian freedom fighters and Irish, should be of some educational value to culture-challenged Sri Lankan media graffitists and Eelam Tamils as well, in challenging the distortions of Sri Lankan media mouthpieces. I provide the following reasons for giving this comparison.

Reasons for Cross-Cultural Comparison on Collaborators and Informers

First, one can see parallels between the operational and intelligence-gathering tactics adopted by the Israeli armed forces in the Palestinian homeland and the Sinhalese armed forces in the Tamil homeland. This is because the Sri Lankan government armed forces have received armament and training advice from Israeli authorities.

Secondly, Palestinians are Muslims. Thus, the predominantly Tamil-speaking Sri Lankan Muslims identify with them emotionally. But, in Sri Lanka, the Muslims form a noticeable contingent (in the diplomatic and media journalism circles) used by the Sinhala-dominated Sri Lankan government for anti-LTTE bashing. When the LTTE delivers the same treatment to its Tamil collaborators and informers, that their Muslim co-religionists provide in the Palestinian homelands, the Muslim contingent in Sri Lanka either raises sentiments of human rights abuse or keeps mum.

Thirdly, not only the Muslims, even the Sinhalese politicians (especially the likes of President Mahinda Rajapaksa, who himself brags as serving as the President of the Sri Lanka Committee for Solidarity with Palestine since the early 1970s), who criticise the LTTE’s actions on Tamil collaborators and informers keep mum on what Palestine intifada warriors do to collaborators among their clan.

Fourthly, there is an urgent need to educate the Eelam Tamils on behavioral aberrations like collaboration with the enemy, and how cultures faced with similar situations have reacted to such behavioral aberrations. Quite a number of half-baked analysts and commentators of the Sri Lankan scene (Rohan Gunaratna, Radhika Coomaraswamy and the orrespondents assigned to the Colombo beat – Nirupama Subramanian, V.S.Sambandan and Somini Sengupta) have painted grossly exaggerated versions of the fates of collaborators and informers, based on their monocular and erroneous lens of ‘human rights abuse’.

American, Palestinian and Irish examples

The complete texts of the following articles, which appeared in Time, The Nation (New York) and The New York Times between 1972 and 2006, are presented in chronological order, for the record and reading.

(1) ‘Informers Under Fire,’ by an unsigned author. [Time magazine, April 17, 1972]. This article provides some background history on a few (in)famous informers, from the days of Casanova of the 18th century, and the FBI’s use of informers in America.

(2) ‘Palestinian Collaborators: The Enemy Inside the Intifada,’ by Joost R.Hiltermann [Nation, Sept.10, 1990 and Nov.5, 1990]. This article also provides some details on the fate of collaborators in France and Poland, during the Second World War.

(3) ‘Palestinians trying to root out Informers,’ by Deborah Sontag [New York Times, Jan.19, 2001].

(4) ‘I.R.A. Turncoat Is Murdered in Donegal,’ by Brian Lavery [New York Times, April 5, 2006]

The words of a Palestinian political leader, quoted by Deborah Sontag in 2001 (the third feature mentioned above), is an apt pointer to the Colombo-based human rights activists, who bleat and wail at the drop of a hat when something unpleasant happens to the collaborators and informers in the blessed but divided island. To quote Freih Abu Meddein, “‘The tragedy of our human rights organizations,’ he said on Palestinian radio, ‘is that they talk in the philosophy of those who fund them, not according to their own convictions.’”

*****

Informers Under Fire

[courtesy: Time magazine, April 17, 1972, pp.51-52, an anonymous report appearing under its ‘The Law’ column. The bold-face subheadings and italics, are as in the original.]

Even law-and-order advocates sometimes find their sensibilities offended by that most unstable adjunct of plice work, the informer. Trained from childhood to disparage tattletales, Americans have hardly a decent word for those who give information to authorities. The glossary runs to such pejorative nouns as fink, stoolie, rat, canary, squealer. In some police argot they are snitches. Yet no major police force can operate without some of the shady types who will go where cops seldome can, perhaps to a meeting of conspirators, or do what cops won’t, for example, shoot heroin before a cautious pusher will make a sale. Informers have long been found in every area of life, but since the McCarthy era there has not been so much public concern about them in the US as there is now.

The chief cause has been the recent spate of celebrated cases in which police agents played a role – from the trials of the Chicago Seven and the Seattle Eight to virtually all of those involving Black Panthers. Currently, civil libertarians are questioning the propriety of the prosecution’s use of Boyd Douglas, the FBI informant central to the just-concluded Harrisburg Seven trial. Still more questions have been raised by the ongoing trial of 28 people accused of destroying draft files in Camden, NJ. Four weeks ago, Robert Hardy, a paid FBI informer, suddenly announced that Government money had been supplied for gas, trucks, tools and other items necessary to the raid. He contends that he acted in effect as an agent provocateur, rekindling interest in the project when the others seemed to have dropped it.

Variations: The word informer actually covers a variety of types. They range from the fellow who turns in a friend for tax fraud (and collects up to 10% of whatever the Federal Government recovers) to a full-fledged undercover Government agent like Herbert Philbrick (I Led Three Lives). As Philbrick’s case suggests, the usually unsavory reputation of informers often vanishes if the cause seems especially just – or at least popular. The FBI’s hired hand who fingered the Ku Klux Klan killers of Viola Liuzzo generated considerably less controversy than Boyd Douglas.

For many, informing is a onetime thing. On the other hand, the champion informant in the San Francisco area is responsible for an estimated 2,000 arrests a year, mostly in narcotic cases; a retired burglar, he now earns $700 a month from the police. Not surprisingly, money is a common motive for informers. In 1775, somewhat the worse for his fabled years of womanizing, Casanova replenished his purse by hiring out to the Venetian Inquisitors; he provided them with political tidbits as well as a list of the major works of pornography and blasphemy to be found in the city’s private libraries. The fictional Irish betrayer, Gypo Nolan, in the movie The Informer, turned in his best friend to the British for 20 pounds. A whore-house madam collected $5,000 for leading the FBI to John Dillinger.

But by far the most frequent impetus is the save-your-own-skin syndrome. In return for having the charge against him dropped or reduced, a suspect can often be induced to testify against his confederates. An already convicted man like Joe Valachi may get special privileges and protection. Less often, an informer is a well-intentioned citizen driven by personal zeal, as was the former Communist Whittaker Chambers in his accusations against Alger Hiss and others. Now, sociologist David Bordua points out, “there is a whole new type developing in the area of anti-pollution law. If you like it, it’s civic participation. If not, it’s police informants.”

Danger: Like it or not, most experts regard the typical informer as an indispensable evil in much police work. “A very scurvy bunch”, observes Stanford Law professor John Kaplan, a former prosecutor, but “there are certain kinds of crimes in which you have to have them – consensual crimes like narcotics.” The reason: in such cases there are rarely complaints from the victims. Last year informants on the FBI payroll accounted for 14,233 arrests and the recovery of $51,646,289 in money and merchandise. For all their importance in gathering information, though, they present considerable technical and tactical problems in the courtroom.

Their anonymity is frequently vital. Thus courts allow a tip from a reliable informant to be used to obtain a search warrant – without revealing the informant’s identity. But if failure to disclose his name would unfairly hamper the defendant on trial, then the informer may no longer remain anonymous. Two years ago, Denver Police Lieut. Duane Bordon found that the danger to informers is no Hollywood myth. He was forced to give an informer’s name at a trial, and a few months later the man was found beaten and shot to death.

Pop’s Pot: The use of informers raises a variety of constitutional problems. Under the Miranda decision, police cannot question an arrested suspect without warning him of his right to silence and counsel, but an informer is free to pump an unwary suspect for all he is worth. That was how Jimmy Hoffa was convicted of jury tampering and the Supreme Court upheld the conviction. Moreover, the informer can legally be fitted out with a tape recorder or transmitter. “The theory is that you’ve trusted the wrong person,” explains Professor Kaplan.

The informant planted in a suspect’s cell after his arrest does suggest Miranda problems still unresolved by the Supreme Court. On the other hand, a regular cellmate, not working for the police, may testify about anything he is told. This is because the private citizen is generally permitted a range of freedom denied to an agent of the Government, whose investigative power the Bill of Rights sought to limit.

But when does a citizen informer become a Government agent? The question was sharply if unusually presented in Sacramento, Calif., recently when a twelve year old boy discovered that his father had some pot and turned him in to the police. The resulting conviction might have been upheld if the youth had simply grabbed Dad’s stash on his own; instead, he had returned to his house on police instructions to get the evidence. Thus he became a police agent, and as such, he conducted warrantless search in violation of the Fourth Amendment.

Judicial Control: The issue is particularly critical to a special rule of the game. A policeman or police agent is forbidden to entrap – that is, he may not put the idea of the crime into a person’s head and induce him to act on hit. A mere citizen, however, can suggest a criminal idea and later, if he decides to become an informer, gives evidence against his co-conspirators. Clearly, the moment when he came under police control is crucial.

All of these difficulties make prosecutors loath to use informants as witnesses. Moreover, they are a generally unpredictable lot, and juries frequently discount their evidence on the theory that they may have embroidered their testimony to gain police favor. But the result – the fact that only a minority of informers ever appear in court – helps to reduce the amount of control that judges have over their use. Many who worry about informers and police power would like to see more, not less, of such judicial control. Aryeh Neier, executive director of the American Civil Liberties Union, thinks that the use of police informants should be permitted only after a judge issues a warrant. Others, like Illinois Attorney Joseph R.Lundy writing in The Nation, focus their objection narrowly on political investigations. They would require a warrant authorizing the use of informers when First Amendment free speech rights are involved.

Basically, the issue is so emotion laden and complex because it leads to a direct conflict between a citizen’s right to privacy and society’s right to protect itself against crime. That tension has existed since the framing of the Constitution, and resolving it is one of the burdens of a free society. Meanwhile, informers are not going to disappear and neither can the search for safeguards against their improper use.

*****

Palestinian Collaborators; The Enemy Inside the Intifada

by Joost R.Hiltermann

[courtesy: The Nation (New York), Sept.10, 1990, pp.229-234. Joost Hilterman, the author of this article, has been introduced in a foot-note as “a Dutch sociologist and an editor of Middle East Report, has worked with the Palestinian human rights organization Al-Haq for five years.”Italics, dots denoting gaps, and words within parentheses, are as in the original.]

When Samira Mahmoud was cleaning her house in the village of Ya’bad in the occupied West Bank one morning this past June, she suddenly heard salvos of gunfire in the street below.She leapt to the window in excitement, thinking, she recalls, that the strike forces (groups of local activists who implement the directives of the Palestinian national leadership) had killed her neighbor Ahmed Natour, whom she describes as a heavily armed Israeli agent. To her dismay, she discovered that Natour was alive and well; he was simply throwing a wedding party for friends, who were firing their guns in celebration.

On that day, when Sami Najjar married his cousin Ahlam Najjar at the Natour house, the Israeli Army had taken up strategic positions overlooking the quarter; one patrol came down to offer congratulations and drink tea. Soon army and collaborators, including the newlyweds, left town, and quiet returned to the neighborhood.

The Najjars and Ahmed Natour were driven out of Ya’bad by townspeople in 1988. They returned temporarily under army protection in 1989 but have led a roving existence this past year, dividing their time between Haifa in Israel, army camps in the West Bank and homes of relatives in the Ya’bad area. Equipped with Israeli-supplied automatic weapons, they have terrorized the local population, assisting the army in making arrests, manning impromptu roadblocks and beating and kidnapping Palestinian activists.

Omar Kilani, a 25-year old Ya’bad resident, recalls how on July 12, 1989, he and four others were stopped at a junction near the village by the brothers Ali, Omar and Bassam Najjar and two others, all known as collaborators among the local population. The five dragged Kilani out of the car and beat him with rods on the lower legs and abdomen. He lost consciousness and, when he came to, found himself in the Najjars’ white BMW, his hands tied behind his back. The men drove him to an olive orchard and began an interrogation, with an Uzi to his head, about the death a month earlier of Khaled Hirzallah, another Ya’bad resident, who had been accused of collaborating with the occupation army. Then they took him to the Fahmeh military camp, which has served for the past year as a dormitory for some twenty-five collaborators and their families expelled from their villages during the uprising. There Kilani was beaten again. After briefly losing consciousness, he was checked by an army doctor. A jeep transferred him to military headquarters in Jenin, where he was kept for sixteen days without treatment before being placed in administrative detention, without charge or trial, for six months in the Negev desert.

Incidents such as these help explain the deep hatred Palestinians have for those who act in league with the military occupation, as well as the joy they express at the news that the resistance has killed a collaborator. But such incidents are largely absent from any discussion in the West, where a propaganda campaign launched by the Israeli government has succeeded in extracting the issue of retribution from its historical and political context and has instead characterized it in the Orientalist syntax of ‘intercommunal strife’ among ‘Arabs’. In a document distributed to the foreign press in December 1989, ‘The Intifada Against Arabs’, the Israeli government claims that ‘most of the attacks cannot, by any dint of the imagination, be connected to charges of collaboration.’ The intifada, ‘besides being used as a cover for forcing the population into compliance with the PLO and for ‘settling scores’ between rival terrorist and criminal groups, also enables ‘brutal gangs to terrorize the population and engage in sadism, rape and blackmail.’ The pro-Israel lobby in the United States has followed suit, coining the phrase intra-fada.

The Israeli spin on the collaborator issue resonates throughout the Western news media. ‘The intifada turns against itself,’ announced the Economist last September. A month earlier Jackson Diehl of the Washington Post reported from Ya’bad that the Najjar family had been ‘plunged into one of the savage episodes of inter-Arab violence that increasingly characterize the uprising,’ even as he conceded that the Najjars are heavily armed, enjoy military protection and are ‘openly allied with the Israelis’. On Nightline, following the massacre of seven Palestinians by Ami Popper earlier this year, Ted Koppel tried to bully Palestinian activist Hannan Mikhail-Ashrawi by saying that anyone who acts independent of the PLO risks execution as a collaborator: “Assuming for a moment that there are…men and women on the West Bank, in Gaza, who would be willing to talk with the Israelis [without PLO sanction], you know as well as I do that if they did, they’d be dead the next day.” In this Koppel was reinforced by his other guest that night, Israeli Deputy Foreign Minister Binyamin Netanyahu, and in fact it is the official government position, as expressed by the Israeli consulate, that “a primary motive for this violence has been to smother budding moderation which might lead to dialogue with Israel.” This is a brazen claim – as Ashrawi was quick to point out – particularly considering that Israel’s policy since 1987 has been to deport or incarcerate any actual or potential local leadership in the occupied territories. It is also untrue. With a few exceptions, there has been considerable tolerance for a wide range of political opinions in the Palestinian community during the intifada, and no one has been killed expressly for his or her beliefs. The Associated Press in Jerusalem compiled a list of 207 collaborators killed between December 1987 and May 16, 1990. Although several of those killings may be attributed to simple crime, not one of them can be ascribed to political rivalry among Palestinian factions. Nevertheless, Israeli propagandists have made their definitions stick: A collaborator is any Palestinian who is in any way attacked physically or verbally by fellow Palestinians for whatever reason.

What has dropped out of the narrative is the Palestinian definition of collaborators as those who work for the enemy against their own people, and have therefore forfeited their right to membership in the Palestinian community. As Raja Shehadeh, a Palestinian attorney, explains, it is “impossible to talk about the killing of collaborators only on the level of what is right and what is wrong. There is also the level of law and order. We know that the Israelis in their administration of the occupied territories are actively encouraging criminals.” These criminals, he says, are recruited to work for the occupation, and they receive army protection. “The army are accomplices to crime,” Shehadeh contends. “The population’s treatment of collaborators cannot be spoken of only as evidence of criminality when the criminality begins with the occupiers themselves.”

The practice of eliminating agents of a colonial or occupying power by an indigenous resistance movement has plenty of precedents. During World War II, the French maquis, without any form of legal process, killed many French citizens accused of spying for the Nazis, and Jewish resistance fighters in the Warsaw ghetto made no bones about killing Jewish collaborators – a necessary step, argues Holocaust survivor and human rights activist Israel Shahak, in preparing for the 1943 ghetto uprising. In colonial Africa, in those cases where nonviolent options of decolonization had been closed off, invariably the local emissaries of the colonial power were more accessible, more easily identifiable and therefore the first to be attacked. In South Africa, activists in the black townships have ‘necklaced’ collaborators despite international condemnations.

The role of enemy agents and the threat they pose in serious confrontational situations is of course well understood by people engaged in military actions on both sides of the divide. A forthcoming book by Kathy Bergen, David Neuhaus and Ghassan Rubeiz quotes an Israeli reserve soldier who had earlier made clear that in no way had he ever identified with Palestinians and their struggle during his stint in the West Bank: “We could not understand how those people were still alive,” he said of the collaborators. “As Israeli soldiers…we had to work alongside these collaborators, and we could not understand how the people in the village did not beat their brains out.”

In the West Bank and Gaza, collaboration is as old as the occupation. Israel’s internal intelligence service, the Shin Bet, has recruited Palestinian agents since 1967, especially in prisons and among the criminal element, such as drug dealers and prostitutes. From the beginning their tasks included spying on neighbors, turning in those who were active in the resistance, assisting the army in making arrests and interrogating detainees. Others acted as middlemen between the military government and the population by issuing permits in exchange for bribes, while yet others sold village lands to Israelis, often forging signatures on deeds. The latter were often armed. In the revolutionary climate of the first months of the intifada, Palestinians flushed out great numbers of informers and pressed them to turn in their weapons and recant publicly in mosques and churches. Other collaborators fled to Israel, especially after the watershed lynching of an armed collaborator in the village of Qabatiya in February 1988.

Today entire communities in Israel serve as repositories for ‘burnt’ agents, like Maqer near Acre, Dahaniya just outside the Gaza Strip on the Egyptian border, and Jaffa. Here collaborators pass their days like so many spent cartridges, living on a government allowance in dilapidated apartments, usually without jobs but armed and prone to crime. Last October an armed collaborator from Jabalya refugee camp in Gaza who had been relocated by the Shin Bet to Israel was arrested for the murder of seven prostitutes, drug addicts and pimps in Tel Aviv and Jaffa. After some of the former agents complained publicly about their predicament this past May, the Shin Bet reportedly threatened to revoke their car and business licenses and said they would be sent back to the West Bank and Gaza if they continued to talk to the press.

The collapse of the informer network early in the intifada dramatically weakened Shin Bet intelligence and undermined the military government’s control over the population. For almost a year, the resistance was able to organize freely in towns, villages and refugee camps. To regain control, the authorities had to find new sources of information. This was accomplished through large-scale administrative detention (a measure not requiring evidence of illegal activity) and mass arrests of demonstrators and stone throwers. From among this new prison population, the Shin Bet began rebuilding its network of informers through a proven recipe of privileges, coercion and blackmail, including threats to imprison relatives or deport spouses who lacked proper residence documents. By the spring of 1989, new informers were in place, while those who had fled in 1988 were now equipped with weapons and encouraged to move back to their homes under army protection and participate in military operations against activists. In November 1989, Defense Minister Yitzhak Rabin acknowledged “security personnel and collaborators” had carried out joint military operations in the occupied territories.

The return of the collaborators put the national movement on the defensive. Now the enemies in their midst were heavily armed and out for revenge. In Ya’bad the Najjars and Ahmed Natour moved back into their homes in August 1989, two weeks after the army had set up a branch of the military government in the village. During the day, they worked for the army bureaucracy, making a living charging fees from residents seeking building permits, driver’s licenses and the like. Several young men were injured by the Najjar’s gunfire when the population tried once again to evict them. Eventually, they moved out themselves, and have returned only sporadically to assist the army in making arrests or to terrorize residents. This past April 10, for example, Omar Najjar and his cousin Sami Najjar opened fire at a house in the hamlet of Nazleh, frightening the inhabitants before being chased off to the shelter of the adjacent Israeli settlement of Shaket.

Last year, in tandem with the Shin Bet’s frenzied recruitment efforts, killings of collaborators rose sharply, reaching a peak of twenty one deaths in September. The army responded by punishing those suspected of killing collaborators by dynamiting their relatives’ homes. International opinion, primed with Israeli propaganda, condemned what appeared to be an epidemic of killings. Inside and outside the territories the Palestinian leadership began to reassess its position. Already in August 1989 the Unified National Leadership of the Uprising, which has given direction to the intifada, appealed to the population “not to liquidate any agent without a central decision by the higher command.Nor should any suspected agent be executed short of a national consensus on that decision or before he is warned and given a chance to repent.” In December 1989 the Nablus branch of Al Fatah, fearing it was losing control of its own strike forces, echoed in a leaflet an earlier call by Yasir Arafat to end the killing of collaborators in the city. Indeed, no collaborators have been executed in Nablus since then, as far as can be known from the A.P. list.

In general, however, local strike forces seem to be acting at their own discretion, responding, to leaders I spoke with say, to local conditions and pleading self-defense. Other observers suggest that the wide scale arrest of cadres has depleted the ranks of local activists, shifting responsibility for the defense of communities to young and relatively inexperienced militants. These are often disgruntled, even ‘thuggish’ elements, whose hallmark has been “excessive retribution” for even minor forms of collaboration, says Palestinian sociologist Salim Tamari. They had additionally undertaken a “moral crusade”, in some cases punishing drug dealers and prostitutes who were not also Israeli agents.

Faisal Husseini, a Palestinian leader who advocates a nonviolent political struggle against the military occupation, has refused to dissociate himself from the liquidation of collaborators, though he opposes the killing of “innocent people”. But, Husseini says, “noone can promise there will be no mistakes.”

Excesses clearly have occurred. In June 1989, Khaled Hirzallah was interrogated by a Ya’bad strike force and died shortly after being returned home. Activists in the village say that the strike force had not intended to kill him because he was only a small-time collaborator for whom a stiff warning would suffice. In Tulkarm refugee camp, nationalist leaders meted out a punishment of forty lashes to the leader of a local strike force who sexually molested a young woman accused (falsely, it turned out) of collaboration last April.

The army and Shin Bet have tried to take advantage of popular discontent with excesses committed by the strike forces by kindling suspicions and factional rivalries in villages. In Ya’bad, local activists I spoke with cite the Hirzallah case as an example in which the death of a person not publicly known as a hard-core collaborator caused frictions among families and political factions in the village, so much so that the leadership committee, which combines all factions of the PLO present in the village, threatened to split. The army established its government branch in Ya’bad shortly thereafter, ostensibly to ‘restore order’. It was then, activists say, that “people realized that [through their conflicts] they had created an opening for the military to move in.” In other places, the Shin Bet has distributed leaflets, usually signed by unknown nationalist groups, listing the names of residents who, according to the leaflet, are suspected of collaboration. One such leaflet, distributed in the village of Kufr Na’meh this past June, mixed the names of real collaborators with those of nationalist activists. The leaflet caused momentary confusion in the village until the local leadership exposed it as a Shin Bet forgery.

In the third year of the intifada, collaborators continue to pose a serious threat to the resistance, according to local organizers, but it is becoming increasingly difficult to get rid of them. One leader in Ya’bad said: “We must have minimal national unity. To kill ‘hidden collaborators’ means shaking up this unity. People ask, ‘Why did you kill this guy? He is innocent.’ That’s why it is necessary to have clear evidence, to show that the person is 100 percent guilty. In times of popular revolution,it is easy to get rid of collaborators, but when the tide turns, like now, it isn’t. So we have to be careful who we choose, and how we do it.”

A friend of Ahmed Natour’s, a collaborator by the name of Muhammad Hamarsheh, was killed near Ya’bad in January. And Natour himself has it coming, though it may prove difficult to pull off: “He is armed and has army protection,” the activist said. “There are no weapons in this village. We keep asking the PLO leadership for help, and the answer always is, ‘You cannot kill the collaborators; you’ll have to learn to live with it.’ But we will not listen to this. As soon as the mouse is in the trap, we’ll get him. Why? Because he’s dangerous. He is trying to destroy our society.”

*****

Aftermath of Hiltermann’s Article; Two letters and a rebuttal

Hiltermann’s article led to two published letters to the Editor, and a rebuttal by Hiltermann. These appeared in a subsequent issue of the Nation (Nov.5, 1990, p.510). For record, I provide below these as well.

Letter 1: Joost R.Hiltermann asks us to understand the Palestinian definition of collaborators as ‘those who work for the enemy against their own people, and have therefore forfeited their right to membership in the…community.’ And, as he explains elsewhere, this means their right to live [‘The Enemy Inside the Intifada’, Sept.10]

Hiltermann should recall Mussolini’s definition of fascism as ‘the people bound together to form a weapon.’ The essential binding of the fascist weapon, then and now, is the liquidation of any voice that dissents from the state’s choice of enemy. But under the arrangements Hiltermann defends, any Arab who begins to think that Israel is not the enemy, and to act on this opinion, is a collaborator and liable to liquidation. I conclude that Hiltermann wants us to be sympathetic with the defining feature of fascism. Is that what he really intends? - W.M.McClain, Detroit.

Letter 2: Joost R.Hiltermann contends that the murders of Palestinian ‘collaborators’ by Palestinian hit squads are justified, even if on occasion there are what he calls ‘excesses’.

Yet the only ‘excesses’ that Hiltermann chose to mention were a case in which a ‘small-time collaborator’ died at the hands of ‘activists’ who ‘had not intended to kill him’ and a case in which a member of a Palestinian ‘strike force’ was punished by his colleagues for molesting a woman who had been falsely accused of collaboration. Hiltermann thereby left the erroneous impression that the few unjustified assaults on Palestinians by Palestinians are either accidental or involve punishment of the perpetrators. There is, however, considerable evidence that a signficant number of the hundreds of murdered Palestinian ‘collaborators’ were actually slain for altogether different reasons and posthumously labeled ‘collaborators’ as a cover.

In January, Issa Shina of Khan Yunis was stabbed and seriously wounded by eight masked men who accused her of ‘immorality’, and Jumaa al-Madani, of Absan, was stabbed by six masked men who accused him of ‘sexual depravity’ because he was seen in the company of a widow. In March, Fatima Abu-Najeh, of Gaza, was hacked to death because she was a prostitute. In April, Imad Sikali was strangled in the Ketziot prison camp as a result of a sexual dispute with fellow prisoners. Numerous other victims who were denounced as collaborators were in fact targeted as a result of clan disputes, the settling of scores by underworld figures, personal grudges, petty crime or attempts by Muslim fanatics to impose medieval standards of morality.

The murders have become so uncontrollable that the intifada leadership itself has repeatedly been forced to acknowledge that some of the victims are not collaborators. A gang of ax-wielding Arabs hacked to death Ma’mun al-Masri, a teenager, last December because he resembled a suspected collaborator; after the error became apparent, the Unified Leadership of the Uprising declared al-Masri to be a ‘martyr of the revolution’. Ahmed Anturi, 26, was bludgeoned to death in Kalkilya in July by masked men who labeled him a collaborator; the Uprising Leadership subsequently issued a leaflet criticizing the executioners for murdering ‘a respectable citizen’. In view of such savage behavior, is it any wonder that most Israelis fear the consequences of a Palestinian state in their backyard? – Bertram Korn Jr., Committee for Accuracy in Middle East Reporting in America, Philadelphia.

Joost Hiltermann’s Rebuttal to the Two Letters

Had W.M.McClain not permitted his emotions to blur his critical faculties, he would have understood from my article that collaborators who forfeit their right to membership in their communities are no longer welcome in those communities; they are expelled, usually after repeated warnings. That’s why one can find large colonies of burnt agents in Israel these days. Many of those who have been killed were armed and used their weapons to terrorize the civilian population on behalf of their handlers in the Israeli internal intelligence service, the Shin Bet.

I was intrigued by what McClain may have meant with the phrase “and to act on this opinion.” Does that include arresting, interrogating, beating and firing on unarmed civilians, as it invariably does? A person similarly acting on his “opinion” in the United States would soon be behind bars. Unfortunately (or perhaps I should say fortunately), Palestinians do not have such facilities in the occupied territories. By his logic, would McClain label Jewish resistance fighters in the Warsaw ghetto “fascists”?

Bertram Korn says, based on “considerable evidence,” that the excesses I referred to in the killing of collaborators are not aberrations. He lists several examples without, however, breaking any new ground, and without presenting evidence, or stating his sources. What is Korn’s source? It turns out to be The Jerusalem Post, from which he quotes without attribution. Moreover, Korn tampers with the skimpy and unreliable references to collaborator killings in the Post. In the Sikali case, for example, the Post states, “Military sources said the victim…had been slain in a ‘sexual dispute’, but Palestinians said he had cooperated with prison authorities” (my emphasis). Korn conveniently suppresses the Palestinian side of the story. He likewise omits relevant information in the case of Fatima Abu-Najeh. According to the Post: “Abu-Najeh was accused of prostitution, and transmitting information obtained from her clients to the security services.”

In the Kalkilya case, Korn assumes that nationalists killed Anturi because the Unified Leadership condemned the deed. But the killing has not been claimed by anyone (unlike collaborator killings, which are invariably claimed by some faction or other) and was expressly disclaimed by Al Fatah. It is not clear who the culprits are; the military authorities appear uninterested in pursuing the matter (again unlike occasions when a collaborator is killed by the resistance). Finally, there is no evidence at all that the killers labeled Anturi a collaborator; they left neither an explanatory note nor their calling card. It would not surprise me, from the looks of it, if it were a case of agents provacateurs attempting to sow discord in Kalkilya, a common practice in the occupied territories.

Korn’s patronizing suggestion that Palestinians’ “savage behavior” helps explain the fears of most Israelis about a Palestinian state “in their backyard” is particularly repugnant. Once Palestinians assert their right to independence and establish their own state, it will be as Israel’s neighbor, not its backyard. There won’t be a need for “savage behavior” at that point because, absent the military occupation, there will be no collaborators. Palestinians will have a state apparatus equipped to deal with conflicts that may arise. In the current situation the Israeli authorities aid crime and collaboration while ignoring the murder of Palestinians by Israeli agents.

Finally, I take issue with Korn’s contention that I justify the killing of collaborators. For moral and political reasons I am opposed to the killing of human beings in any context, although I can understand why collaborators are killed in the occupied territories. I speak from the sanctity of my office, however. I am not altogether sure what I would do if I were a Palestinian struggling to free my country from a brutal military occupation and a relative or friend of Amer Amro (16, from Dura), who was shot dead by a collaborator last April as he and his friends set up a barricade at the entrance to their village. That was reported in The Jerusalem Post and therefore, of course, acceptable to Korn and his organization. – Joost R.Hiltermann, Ramallah, West Bank.

*****

Palestinians Trying to Root Out Informers

by DEBORAH SONTAG

[Courtesy: New York Times, January 19, 2001]

BETHLEHEM, West Bank: In a muffled hoarse voice, a Palestinian confessed today on Voice of Palestine Radio to being a paid informer for Israeli security forces who, he said, had used threats of exposure, imprisonment and death to keep him in line. It was one of a series of such confessions that is being broadcast in a campaign by the Palestinian Authority to root out traitors, an effort that has led ‘several hundred’ Palestinians to turn themselves in this week, officials said.

The campaign began with executions last weekend of two ‘collaborators’ after their convictions in lightning trials for assisting Israel in assassinating Palestinian militants. The executions enjoyed broad support, even from some elite critics of the Palestinian government. One critic, Daoud Kuttab, wrote in a newspaper today that at first ‘it seemed to me the Palestinian National Assembly had no choice but to take radical deterrent steps.’ Since the executions, however, the Palestinian campaign -- the justice minister gave informers 45 days to surrender -- has fueled a parallel freelance effort. Gunmen have taken it on themselves to eliminate several suspected ‘collaborators.’

As of Wednesday, gunmen apparently extended the extrajudicial slayings to a senior Palestinian official, Hisham Mikki, who was notorious in Gaza for his supposed corruption. In a fax to Reuters today, a Palestinian group that calls itself the Aksa Martyrs Brigade claimed responsibility for the killing, saying it was necessary because Yasir Arafat, the Palestinian leader, had not clamped down on corruption. The furor has stirred some concern in the West Bank and Gaza that the pursuit of traitors could be unleashing a wave of lawlessness in Palestinian society, deepening internal conflicts and undercutting the struggle against Israel. Others said they thought that although the potential for chaos was great, the internal tumult was inevitable and could be cathartic.

The Palestinian uprising that began in late September united a deeply riven society and distracted people from their disenchantment with their government's supposed corruption, elitism and failed peace efforts. For months, frustration was directed at Israel. But now some of it seems to be boomeranging, especially as talks with Israel are renewed as violence continues and privation intensifies. ‘To witness again, after everything that has taken place, negotiations without results was bound to revitalize the unresolved frustrations,’ Dr. Hisham Ahmed, a political scientist from Bir Zeit University, said. ‘It comes as no surprise to see the intifada turning inward, in part. Now we can expect that resistance against the occupation will take place at the same time as an attempt to try to cleanse the Palestinian house internally.’

Officials said ‘several hundred’ Palestinians had come forward to acknowledge ‘relations and collaboration’ with the Israelis. Most are being interrogated and imprisoned, including 40 jailed in Hebron. But they are promised ‘a rapid absorption’ back into society, officials said. ‘Forty-one days left,’ a Palestinian radio announcer said on Wednesday, advertising the amnesty program. ‘Forty-one days, an opportunity that will never come again.’ Mr. Mikki, whom many Gazans disdained for flaunting his affluence and proximity to power, was killed in the restaurant of a beachside hotel close to Mr. Arafat's compound in Gaza. Hooded gunmen interrupted his afternoon tea. They used silencer-equipped weapons and fled.

The Palestinian Authority declared Mr. Mikki a "martyr," suggesting that collaborators had killed him, and gave him a muted martyr's funeral today. Mr. Arafat helped carry his flag-draped coffin from a mosque to a military car bound for a cemetery, declaring his killing ‘a big tragedy.’ Given the brazenness of the attack in an elite restaurant close to Mr. Arafat's headquarters, many in Gaza suspected an internal settling of scores. Israeli officials said they believed that Mr. Mikki had been killed by paramilitary operatives connected to the official security forces, because he had been caught embezzling government funds and ignored warnings to stop embezzling.

The Aksa Martyrs statement, which some Palestinian suspected was not authentic, described his death as the ‘ruling of the people’ against someone who, it said, had misappropriated significant sums of money and also sexually harassed his female employees. ‘The failure of the authority and its president to punish those filthy people has pushed us to punish them,’ said the statement from the group, which has previously said it was responsible for attacks on Israeli targets.

Here in Bethlehem today, gunmen fired in the air as they marched to protest the delayed executions of two men convicted last weekend of being informers. The marchers belonged to a branch of Mr. Arafat's Fatah organization. After the executions over the weekend, the European Union implored Mr. Arafat to defer the Bethlehem executions and put a moratorium on the death penalty. Some Palestinian human rights advocates also spoke out strongly against the rapid trials, which have been held in the security courts that were created to deal with Islamic terror organizations, and the summary executions.

The justice minister, Freih Abu Meddein, scoffed at the criticism, which he said was hypocritical in view of their muted response to assassinations by Israel, and at the local critics, whom he accused of self-interest. ‘The tragedy of our human rights organizations,’ he said on Palestinian radio, ‘is that they talk in the philosophy of those who fund them, not according to their own convictions.’

The reaction to the executions intensified after Channel 2 television in Israel broadcast graphic reports of the one on Saturday in Gaza. The other was in Nablus. The report showed a row of masked Palestinian police officers firing bullets into Majid Mikawi, who wore a hood and died tied to a stake. Outside the camera's frame, a cacophony of cheers rose after the final bullet had been fired.

Palestinian officials were furious that the tape had been made and distributed. They had refused journalists' entry to the scene of the execution, the parade ground of the Gaza police station. A senior official said the action was not something that the international community understood. On Wednesday, the Palestinians arrested a Gazan camera operator who works for Channel 2 on the suspicion that he had been involved with the tape. He denied involvement, and the Gazan journalists' union protested his arrest. In his column today in The Jerusalem Post, Mr. Kuttab said that after reflection and debate he had somewhat changed his mind about the executions as necessary "radical deterrent steps" in the context of a ‘war.’

Friends had told him that they saw the executions and the crackdown on informers as the Palestinian Authority's way to insulate itself from accusations of its own collaboration with Israeli security forces, he said. He began to think, Mr. Kuttab added, that those people who were executed were being scapegoated. ‘They are yet one more reason,’ he wrote, ‘why this crazy situation should not be allowed to continue and a just peace must prevail.’

*****

I.R.A. Turncoat Is Murdered in Donegal

By Brian Lavery

[Courtesy: New York Times, April 5, 2006]

Denis Donaldson, a former member of the Irish Republican Army who was exposed last year as a British spy, was found shot dead Tuesday evening at his isolated home in Donegal. Ireland's justice minister, Michael McDowell, confirmed that Mr. Donaldson had taken a shotgun blast to the head, and that his right forearm was 'almost severed,' a mutilation similar to those inflicted on I.R.A. informers throughout Northern Ireland's sectarian conflict. Mr. McDowell said Mr. Donaldson, 55, had been tortured in his home near Glenties, in northwest Ireland, The Associated Press reported.

In a statement, the I.R.A. denied any involvement, but the killing threatens the fragile equilibrium that has lasted since last summer, when the group declared an end to its war against British rule in Northern Ireland. In 2002, Britain accused Mr. Donaldson of spying for the I.R.A. by stealing documents from government offices at the Northern Irish parliament. At the time, Mr. Donaldson was receiving paychecks from the British intelligence agencies MI5 and Special Branch while he was serving as Sinn Fein's chief administrator for the power-sharing provincial parliament. The charges brought down the coalition that was formed under the Northern Ireland peace accord of 1998.

His killing came just two days before the Irish and British prime ministers, Bertie Ahern and Tony Blair, are to meet in Northern Ireland to discuss restoring the local government. Mr. Donaldson's spying for the British became public last December after the 2002 spying charges against him and two others were dropped suddenly by the British government. After he was informed that the charges were being dropped, he admitted his dual role to his Sinn Fein colleagues, an announcement that came as one of the movement's most embarrassing scandals in years. When he confessed in December, he told the state broadcaster RTE, 'I was recruited in the 1980's after compromising myself during a vulnerable time in my life.' He added, 'I apologize to anyone who has suffered as a result of my activities, as well as to my former comrades, and especially to my family, who have become victims in all of this.'

Gerry Adams, president of the I.R.A.'s political wing, Sinn Fein, after personally offering his condolences to Mr. Donaldson's family, said: 'It has to be condemned. We are living in a different era, and in the future in which everyone could share. This killing seems to have been carried out by those who have not accepted that.'

Ian Paisley, the leader of Sinn Fein's Protestant rivals, the Democratic Unionists, said the killing 'has put a dark cloud' over the talks Thursday between Mr. Ahern and Mr. Blair. 'Eyes will be turned towards I.R.A./Sinn Fein on this issue,' Mr. Paisley said.

As the province's largest party, the Democratic Unionists are exercising a de facto political veto by refusing to share power with Sinn Fein. Mr. Blair and Mr. Ahern plan to restart the fledgling legislature in May, despite Protestant worries about the continued existence of the I.R.A. Many Northern Irish republicans, who want the province to break away from Britain and join Ireland, might be happy to see Mr. Donaldson dead, and Mr. Adams suggested that his death might have been the work of British intelligence agencies seeking to move blame back toward the republicans.

Mr. Donaldson had earlier earned his bona fides as Mr. Adams's cellmate when they were jailed in the 1970's. He was also arrested after training in guerrilla warfare with Hezbollah in Lebanon in the 1980's. Since his admission of spying and his expulsion from Sinn Fein, Mr. Donaldson seemed to age decades. When he finally admitted that he had been spying for the British, he fled his home in Belfast to a remote part of County Donegal, and a cottage that had no electricity or running water. Hugh Jordan, a journalist who found Mr. Donaldson and reported on his situation recently, told the Press Association in Britain that 'he looked like a hunted animal.'

'He was extremely depressed,' Mr. Jordan said after the killing. 'The nerves in his eyes were trembling. He seemed like a man who didn't think he would come to any harm. He did not see his life to be in any danger, but felt the only future he had was where he was, living in that dreadfully squalid situation. He was alone and threatened no one. He was no harm to anybody.'

© 1996-2026 Ilankai Tamil Sangam, USA, Inc.

Every liberation movement (the American revolutionary war of the 1770s, the French revolutionary war of the 1790s, the Chinese Communist revolution of the 1930s and 1940s, the Cuban revolution of the 1950s and the Vietnam war of the 1960-70s) has spawned collaborators and informers. If one reads history, Fate has never been kind to such nasty deviants who, for convoluted reasons, consorted with the enemies of their clan/tribe/ethnic group/religion.

Every liberation movement (the American revolutionary war of the 1770s, the French revolutionary war of the 1790s, the Chinese Communist revolution of the 1930s and 1940s, the Cuban revolution of the 1950s and the Vietnam war of the 1960-70s) has spawned collaborators and informers. If one reads history, Fate has never been kind to such nasty deviants who, for convoluted reasons, consorted with the enemies of their clan/tribe/ethnic group/religion.  ~1987

~1987