by Varathas, Diasporaland.tumblr, October 2015

While working on an Al Jazeera documentary on Sri Lanka, I stumbled upon raw landscape footage of Jaffna. The camera captured the lush green, rural landscape of the peninsula in beautiful dawn light. Watered paddy fields, palm groves in the distance, thick jungles on the sides, narrow pathways elegantly drawn through fields, farmers going to harvest the fields, cyclists on their way to work and school girls rushing to attend local schools. At its backdrop you could here the voices of birds, chicken and devotional songs escaping from a temple. The images were surreal, almost as if they escaped a kitschy painting or romanticised memory of an elderly, diasporic person. Too romantic to depict reality, too kitschy to ever frame on a wall – unless in exile.

I looked at the stills and asked the producers if I could take few minutes off to take a look at them. The white-only team was surprised. I had to explain to them why I wanted to see them, why these images opened layers of meaning they had no access to. They let me take a break and provided me with more fillers that I could view in peace. Although I’ve been to the country before, during its war, we weren’t able to go to any of my ancestoral places of origin due to imminent fears of violence. I’ve essentially never seen Jaffna but in war, destitution and destruction through megapixels on flickering screens through polyster wires and strangers’ lenses, or rare sepia and black and white potrait photography that had survived war, displacement and exile.

I put my headphones on and sat there, watching an almost motionless tropical landscape in a sound studio in Soho. The seconds kept on rolling, little change was to be seen in the scene. Soothing sounds of a warm morning entered my ear. Although the studio was busy, loud and filled with people, my eyes couldn’t be distracted. I went through shot after shot, indulging in each, playing it back and forth, listening to the music in the background, trying to identify it, not wanting to close my eyes and miss a single motion. I leaned over so deep into the screen that my chair could have lost its equilibrium.

I was unable to place my feelings. But I felt embarassed to sense tears crawling up my eyes. It felt ridiculous to feel emotional about land, any land, and especially this land that I learned to hate. I could sense the producers’ eyes on me. I thought of my parents and aunts and asked myself how I will find the words to describe them what I saw? What I felt? How would they feel, or do I even want to know how they would feel?

Amma used to always tell me in sorrow how she pities us for having had the childhoods we had as refugees. I didn’t understand. What kind of childhood can there be in a land that kills people like us? How can it be better than the childhood we had free of these fears? You don’t understand what you missed in life, she would reply without much explanations. It never made sense to me. Her voice was in the back of my mind when the footage turned from short seconds into long minutes.

Suddenly I could see her walking there, in the midst of this lush green landscape. A landscape I always imagined to be arid and infertile, not green as and rich as it seemed. She blended into the image in front of me only to disappear in its slow motions. For the first time I began to understand her sorrowful words. What we missed as a generation, what exile means, what being strangers means. The female producer interjected: “your country is beautiful.” “My country?”, I stuttered back.

——————

A return in pixels, March 2015

I pulled out my laptop and went on Google Earth. I typed in my mother’s childhood home address, but Google Earth didn’t recognize any matching location. I decided to turn to my mother and carried the spacecraft-like laptop to her. After placing it on top of an orange table mat, I asked her to help me find her parent’s house. She reacted surprised at first, but then went on to ask me if you can see it on there; if she can really revisit home on that stained screen marked by fingerprints. We typed in Hospital Street and the screen started to zoom into the peninsula my mother called home. We began driving down the road with the cursor and our fingers carefully placed on the laptop’s finger pad. While the images constantly shifted between green and light brown patches, she lit up. Her usually tired eyes, worn out by underpaid overtimes, brightened up and started narrating stories of places, encounters and histories. She suddenly looked younger than she had just minutes before; like the girl she’d describe she was but left behind when she crossed that fatal line.

My mother took me on detours around Jaffna Town. Her excitement grew the closer we got to her house. She remembered what she did at this junction, what she did in that park in details that made me question my own twentysomething memory. She recalled these information as if they were only few months old, as if her past was no more than her yesterday. Soon she grew impatient with the my travelling speed. Her stories and memories were overflowing, my drive to memorize hindering. She directed me towards new corners and routes, throwing in colonial, postcolonial and neocolonial street names. She wanted to show me her school, her college, her life in a place she could never take us to or return to herself. I asked myself, is this how ‘a return’ feels like, how home feels like?

Days later we showed the images to my aunt, my second mother, who wanted to show me different places to those of my mother. Our fingers pulled back and forth, both sisters arguing about what to see first while my father and uncle, who were sitting meters from the screen away, were busy throwing in names of even more places to look at. I didn’t know who to prioritize, whose wishes to listen to first; whose longings to queue up. We were excited, loud and emotional. They wanted to remember, to not forget and discover what was left. They wanted to show me, born abroad child of a criminalised diaspora, the home we were never granted to have. They wanted to impress me, western-born, eastern-dispossessed. ‘Life wasn’t always this’, whatever this may be, for them. We were driven by curiosity and nostalgia. I watched them silently, smiling while simultaneously being annoyed by the contradictory instructions I kept on receiving. I was torn observing the joy they had in seeing their homes as pixels; in returning in pixels.

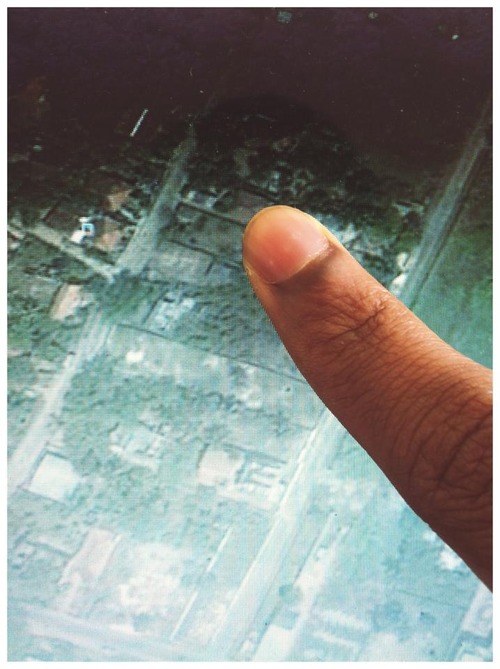

Weeks later, while in Oslo, I sat around the living room with my aunts and cousins who gathered from Canada, UK, Denmark and Germany. Since my cousins had never returned home either, I pulled up Google Earth on the flat screen and told them they could see their childhood homes, their schools, their father’s factory and other places from a distant, by now almost mystical past. When I typed in Manipay, they were able to guide me to their house by merely looking at the rooftops of buildings. One of my cousins stood right in front of the TV screen, pointing with his fingers at places, naming them and confirming them one by one. His voice moved from excitement to overhastiness. Stories started to emerge, memories started to be uncovered and smiles to be exchanged. My aunts, generations apart, desired to see different places to those of my cousins; places of meaning, weight and erosion, places that had different layers of meaning for each generation. In that darkened room, snowed into this Norwegian landscape, they were amazed to be able to watch their tropical home from afar; for technology to ease their pain; for being able to return while being exiled.

Through the reflection of the TV screen mirroring in their eyes, I could see the oceans locked away within them. Everyone had their requests waiting of houses, schools, stores, cinemas, beaches and temples to revisit. Everyone had their wishes to see something they left behind, something they abandoned; something they were forced to abandon and watch fade from their vision. We watched pixel after pixel, they recalled and I recorded. I wanted to capture this moment in some way. To pause, for us to remember our distance, the tragedy of exile, but it was as fleeting as was my visit to Jaffna.

Some return as people, others as pixels.