by Sachi Sri Kantha, August 15, 2015

Three Other Actresses

I should acknowledge that, my convenient choice of heroines and muses in the previous chapter does disservice to three actresses who had been regulars in MGR’s movies. They are, M.N. Rajam, C. R. Vijayakumari and comedian actress Manorama. All three, in their mid or late 70s, are still living. Rajam as well as Vijayakumari were competent heroines, who had shifted to character roles subsequently in numerous Tamil movies. As opposed to other popular heroines of their era whose native tongue was not Tamil by birth (Bhanumathi, Anjali Devi, Padmini, Savitri, Saroja Devi and Jamuna), these three were Tamilians, and their Tamil diction was a forte for their successful careers.

M.N. Rajam had acted in seven MGR movies, released between 1957 and 1966. These include, Mahadevi (1957), Nadodi Mannan (1958), Raja Desingu (1960), Baghdad Thirudan (1960), Thirudathe (1961), Rani Samyuktha (1962) and Thaali Bhagyam (1966). Whereas in MGR’s own production, Nadodi Mannan, Rajam played the third heroine role, for the other six movies, she was the second heroine. Vijayakumari (who was a spouse of S.S. Rajendran), also acted in four of MGR’s movies, namely Kanchi Thalaivan (1963), Vivasayee (1967), Kanavan (1967) and Ther Thiruvizha (1968). Vijayakumari had acknowledged that after her marriage with S.S.R soured, it was due to MGR’s munificence that she was offered roles in Devar Films movies in 1967 and 1968. Comedian Manorama was a constant presence of dozens of MGR movies.

‘Black’ Money in Indian Movie World

The history of the origin of ‘black’ money has been described by Erik Barnouw and Krishnaswamy authentically, in their classic study on Indian Film. They had traced this trait to industrial activity in the first half of 1940s when ‘Indian factories, in spite of the war boycott by the National Congress, were making field guns, machine guns, bombs, depth charges and ammunition for British and Allied forces.’ Illicit profit earned by speculators in various trades were funneled into film industry and came to be identified as ‘black market money’.

There is no doubt that Krishnaswamy is an authentic source, because his father K. Subrahmanyan (a patron of MGR in 1940s and 1950s) was a reputed movie producer, director and speculator. As Barnow and Krishnaswamy illustrated with an example, “a star would receive a one film contract calling for payment of Rs 20,000. In actuality, he would receive Rs 50,000, but the additional Rs 30,000 would be in cash, without any written record. To the star, this extra sum, this payment ‘in black’ was of course tax-free.”

Furthermore, according to Barnouw and Krishnaswamy, an added benefit of this tax-free payment was that it also gave a ‘patriotic tinge’, because in the pre-Independent period, Indian National Congress promoted non-payment of taxes to the British Empire. What was established in the pre-Independent period of early 1940s, continued as a tax-evading tradition, after India entered the post-Independent period. Another tid-bit from Barnouw and Krishnaswamy was the fact, ‘By 1955, star salaries, in the bidding against Bombay, were rumored to have reached Rs 400,000 per film, in white and ‘black’.’

It is a mistake to belief that this sort of black money practice in India is limited to movie industry only. According to a comment by Subrata Chattopadhay, which appeared in the Indian Journal of Medical Ethics in 2008, many professors in private medical colleges in India also are paid a part of their salary (in proportions such as 75:25, 70:30 or 80:20) as black money.

To highlight the role played by black money in the Indian society, poet Kannadasan cavalierly produced a Tamil movie with a stark title, Karuppu Panam (Black Money, 1964). Typical of him, he himself played the villain Thanigasalam role in that movie. A humorous lyric Kannadasan wrote began with the lines,

‘If one has money in hands, even a donkey will be the king,

If there are folks to clap hands, even a crow will be beautiful

If one swims in the lies, the liar will become the leader’

There was some doubt among Tamil movie fans then, whether this movie was a parody of MGR’s public life per se. At that time, relationship between MGR and Kannadasan had been punctured. To deflate Kannadasan’s pride, MGR had offered patronage to a new lyricist, Vaali (birth name T.S. Rangarajan, 1931- 2013).

Roopa Swaminathan had mentioned MGR’s thoughts on black money as follows: “Once, while speaking at a rally, MGR stunned his aides when he openly admitted to talking black money! He explained that film producers generated a lot of black money and if he didn’t talk what was offered, the producers would keep it for themselves. But he took the money and gave it to the poor – a la Robin Hood. What was wrong with that? There were no answers to that question.” However, Swaminathan had failed to provide detailed reference to this comment, as to when, where and in what context MGR made this assertion. Curiously, it was the same logic that was offered by Kannadasan’s villain Thanigasalam character in his Karuppu Panam movie.

Earning a segment of one’s income in black money and tax dodging are two sides of the same coin. In India, movie stars and producers were notorious for tax dodging. Due to his rank as a popular movie hero and a ranking politician, in 1970s, MGR’s image was tarnished as a tax dodger. But, this allegation has to be balanced in proper context. MGR did have company among his Tamil, Telugu and Hindi movie peers. It was revealed in Lok Sabha on March 26, 1982, that almost 60 movie stars (men and women) had a total of Rs. 182,33 lakhs in tax arrears [ One lakh = 100,000]. The movie star who led this list at that time was actress Hema Malini with Rs. 18.11 lakhs. Rest of the movie stars, in decreasing order of tax arrears as of October 30, 1981 were as follows:

Ranbir Raj Kapoor Rs 17.34 lakhs, MGR Rs 9.27 lakhs, M.R. Radha (deceased) Rs 8.52 lakhs, Randhir Kapoor Rs 7.33 lakhs, Savitri Rs 6.93 lakhs, A. Nageswara Rao Rs 6.12 lakhs, Jamuna Rs 5.79 lakhs, Kishore Kumar Rs 5.18 lakhs, Meena Kumari (deceased) Rs 4.67 lakhs, Vijayanirmala Rs 3.98 lakhs, Sivaji Ganesan Rs 3.78 lakhs, Dev Anand Rs 2.98 lakhs, and N.T. Rama Rao Rs 2.39 lakhs.

After he gained status as one the ranking heroes in the Tamil movies in late 1950s, how much MGR was paid (in white and ‘black’) for a movie has not been revealed by him, in his autobiography. To be fair by him, the published autobiographies/memoirs/diary notes/memos of other ranking actors (Sivaji Ganesan, Gemini Ganesan, S.S. Rajendran and Sivakumar) and actresses (Vyjayanthimala) of Tamil movies that I have checked, also don’t include the payments they received, when they were in their peaks. If there is one chronicler of Tamil movie history with insider knowledge, it should be script writer Arurdhas (birth name S. Jesudas, b. 1931). Now in his 80s, he had written 7 books in Tamil, occasionally re-cycling the same anecdotes. He should know because he had written numerous scripts for MGR, Sivaji Ganesan and Gemini Ganesan movies. Even Arurdhas, who has nearly 800 credits for script writing and dubbing, do not provide any numbers on the economics of Tamil movie production and the pay rate for actors, actresses, comedians, villains and extras.

This seems to be a bad omen for not only Indian actors, but even for the Hollywood stars. I have accumulated a collection of over 30 autobiographies and memoirs of Hollywood stars beginning from Chaplin to Michael J Fox. Even if their professional and personal lives were so open, for various reasons (tax purpose, vanity, professional pride etc.), they hardly mention the payments they earned for their hits as well as ‘bombed’ movies.

Ravindar, in his memoirs, passingly mentions that in 1965 (when his super-hit movie Enga Veetu Pillai was being produced), MGR’s payment for a film was Rs. 75,000. It was his 75th movie. According to Ravindar, until MGR reached his 100th movie in 1968, his asking rate didn’t reach Rs. 100,000. But, this rate doesn’t jibe well with the statistic offered by movie mogul A.V.M. Saravanan. In his 2005 memoir, Saravanan informs that MGR was arranged for Rs 300,000 to star in their 1966 production, Anbe Vaa [Come (My) Love], an adoption from 1961 Hollywood movie Come September, starring Rock Hudson and Gina Lollobrigida. Then MGR had a busy call sheet schedule in 1965, and as usual was committed to release one movie in January 1966 as Thai Pongal day release. But the scheduled film was a black and white production of his then manager R.M. Veerappan, under Satya Movies banner. MGR negotiated a better deal with AVM company by postponing the release of this black and white movie, and in the January 1966 slot to release the color production Anbe Vaa of AVM company. For this marginal adjustment, MGR demanded an additional payment of Rs 25,000. According to Saravanan, AVM had to end up paying Rs, 325, 000, to a slight discontent of its founder A.V. Meiyappa Chettiar.

How can one align the discrepant numbers provided by Ravindar and Saravanan for 1965? One clue could be, MGR might have been paid in the range of Rs. 75,000 – 100,000 per movie in ‘white’ and the balance sum ~ Rs. 200,000 in ‘black’ money. Now, 50 years later, considering the crore (one crore = 10,000,000) figures charged by MGR’s successors like Rajinikanth (b. 1950) and Kamal Hassan (b. 1954), MGR’s earned pay looks like peanuts! It is to the credit of MGR that even with the relatively meagre sum he earned then, he gained reputation as a philanthropist. This hardly-earned reputation, even his enemies couldn’t deny. What have prevented either Rajinikanth or Kamal Hassan to achieve such an elite status among the Tamils now?

A Pillar of South Indian [Film] Artistes’ Association in 1950s and 1960s

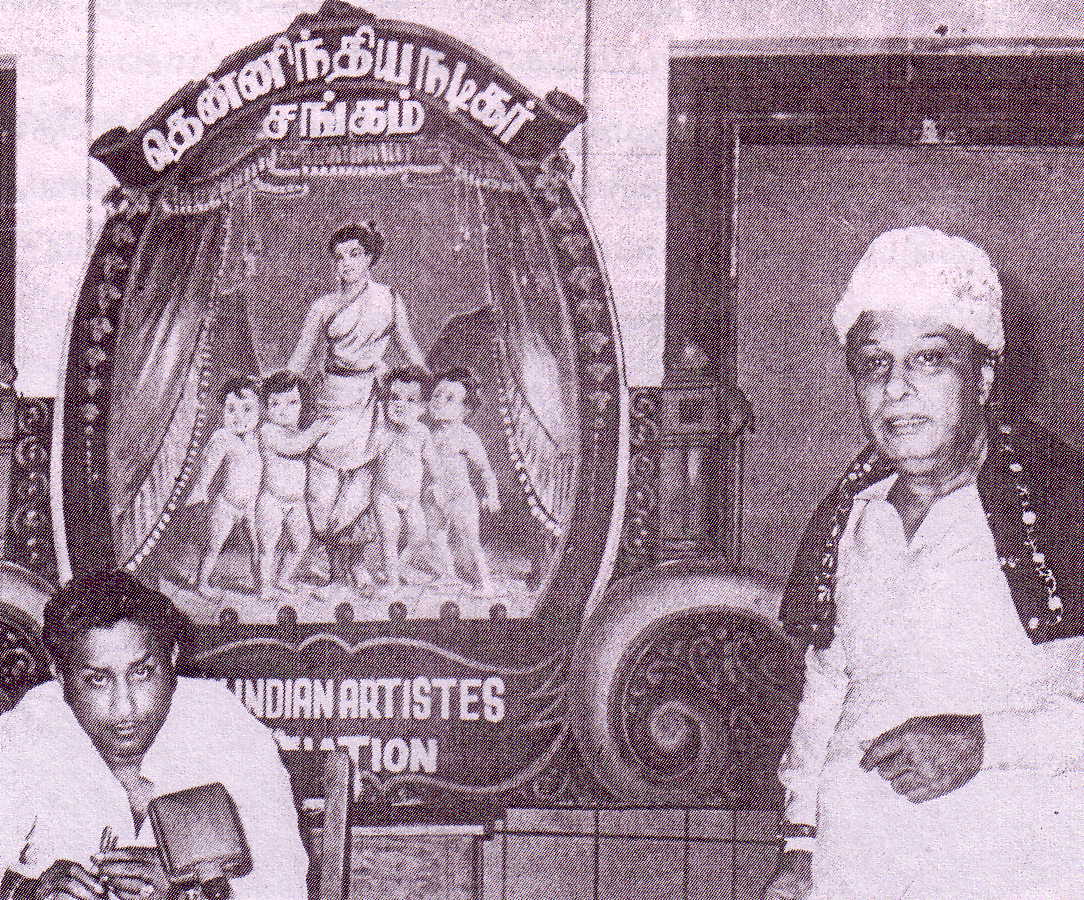

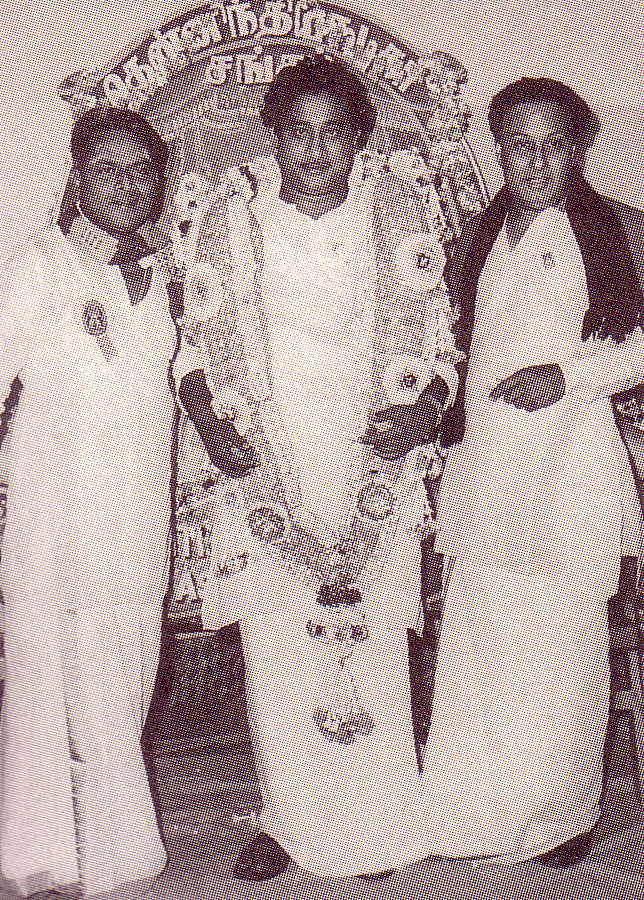

The South Indian Artistes Association [Then-India Nadigar Sangam, aka Nadigar Sangam, in Tamil] was a grouping formed in 1952, to protect the rights and welfare of the community involved in the South Indian movie industry. In late 1950s and early 1960s, MGR was active in this organization as the President as well as the Secretary. Not much information is forthcoming about MGR’s role in establishing this association in the previously published English biographies (Attar Chand, Mohandas, Pandian, Swaminathan and Veeravalli. (see, Parts 7 and 18). Even in his autobiography, MGR had inadvertently ignored this topic.

Why it was so? One can guess that MGR himself knew insider facts and rather than hurting the sentiments of then living artistes, he might have played it safe by ignoring outrightly. Only K. Ravindar and Vidwan Lakshmanan (MGR’s two writing assistants) had offered some meager information they were privy to. Hints recorded indicate that there was much ill-will, antagonism and rivalry among the members of this association. This pattern has not changed even in 2015. Thus, by late 1960s, MGR had relieved himself from this Association. I provide excerpts from Ravindar’s memoirs.

“Mehboob Khan (1907-1964) was a prominent producer-director of Hindi movies. He paid a visit to the Silver Jubilee celebration of Southern India Chamber of Commerce. At the reception function to Khan, MGR also participated. In a speech referring to Mehboob Khan’s past, MGR had told the fact that ‘Mehboob joined the studio as a sweeper and elevated his status step by step’. Some had criticised to such openness. But, MGR stood his ground by saying, ‘Those who hide and forget their past cannot be humans.’ Subsequently, Mehboob Khan and MGR met privately, and I was there too. The foundation stone for the Nadigar Sangam was set then.

Mehboob had expressed the opinion that the community of actors lacked protection and to promote their welfare and demands, there wasn’t even an organization. He also pleaded with MGR to make a ‘revolution’ in setting up such an organization. Ravindar had recorded further,

“Since then, MGR, music director S.M. Subbiah Naidu, director T.P. Sundaram and actor Somu worked actively to organize this Sangam. They also wished to design an appropriate logo. They settled on to the opening greeting song for a drama, penned by lyricist Muthukoothan that had a line stating, ‘Kannada, beautiful Telugu, Tulu and Malayalam’ – four of which were the progeny of Tamil mother. Artist great P. Mathavan was commissioned to create a logo based on this idea for the Sangam. Furthermore, a journal called Nadigan Kural (Voice of the Actor) was started. MGR functioned as the executive editor and Vidwan Lakshmanan worked as the sub-editor.”

In a commentary MGR contributed to the Nadigan Kural (July 1958) entitled, ‘Pitiable state of Film Industry’, he criticized the decision made by government officials in selective distribution of film rolls based on past records of producers. MGR’s view was that, ‘The status of many producers who have a track record may depreciate. Newcomers to the industry may rise to the top, when their debut movie becomes a hit. As of now, no one can predict the success and failure in this business. Therefore, it is not feasible to decide who has the capability or not. Thus, film roll distribution to producers should be well balanced.’

Furthermore, in this commentary MGR also offered few statistics on the distribution of studios and movie theaters in the South. ‘In south India, there are 72 studios. However, both in Bombay and Calcutta the total number of studios were only 99. The total number of movie theaters in India amounts to 4,000. However, south India alone has 2,026.’ These numbers tell a partial story of the success of film industry in south India of 1950s. Though risky, it had attracted much interest of entrepreneurs (akin to the Jews who had a hand in building the Hollywood in early 20th century) who had invested in studios and movie theaters. The outcome being, ten years later, a political trend originated that since 1967, four major chief ministers of Tamil Nadu (Anna, Karunanidhi, MGR and Jayalalitha) had their professional accreditation from film industry. There were two stop-gap chief ministers (V.N. Janaki and O. Pannerselvam), among whom Janaki (2nd wife of MGR) also had movie credit as a heroine.

It could be viewed that in this 1958 commentary, MGR had diplomatically used ‘south India’ (aka, Dravidian India, consisting of Tamil, Telugu, Kannada and Kerala states) to incorporate the movie industries of Telugu, Kannada and Malayalam languages. However in late 1950s, Chennai was the capital of movie production in all four languages, as the number of studios then active in Hyderabad, Bangalore and Trivandrum were relatively few. Majority of the movie producers, actors and technicians also had Chennai as their main base.

Vidwan Lakshmanan had written in his short biography of MGR, that though MGR belonged to DMK party, he functioned impartially to the needs and requests of the film community, even when the requests came from the Congress Party (then in power). In 1957, when the centenary celebrations of the Indian freedom movement was held, MGR was serving as the secretary of the Nadigar Sangam. A request was made by the Congress Party to produce three short dramas for the function, and MGR supervised and directed three such short dramas, depicting the lives of freedom fighters Thirupoor Kumaran, Muthu Vadivu and Veerar Chidamparanar. Among these three, Muthu Vadivu was a heroine and MGR solicited the script-writing help of Lakshmanan.

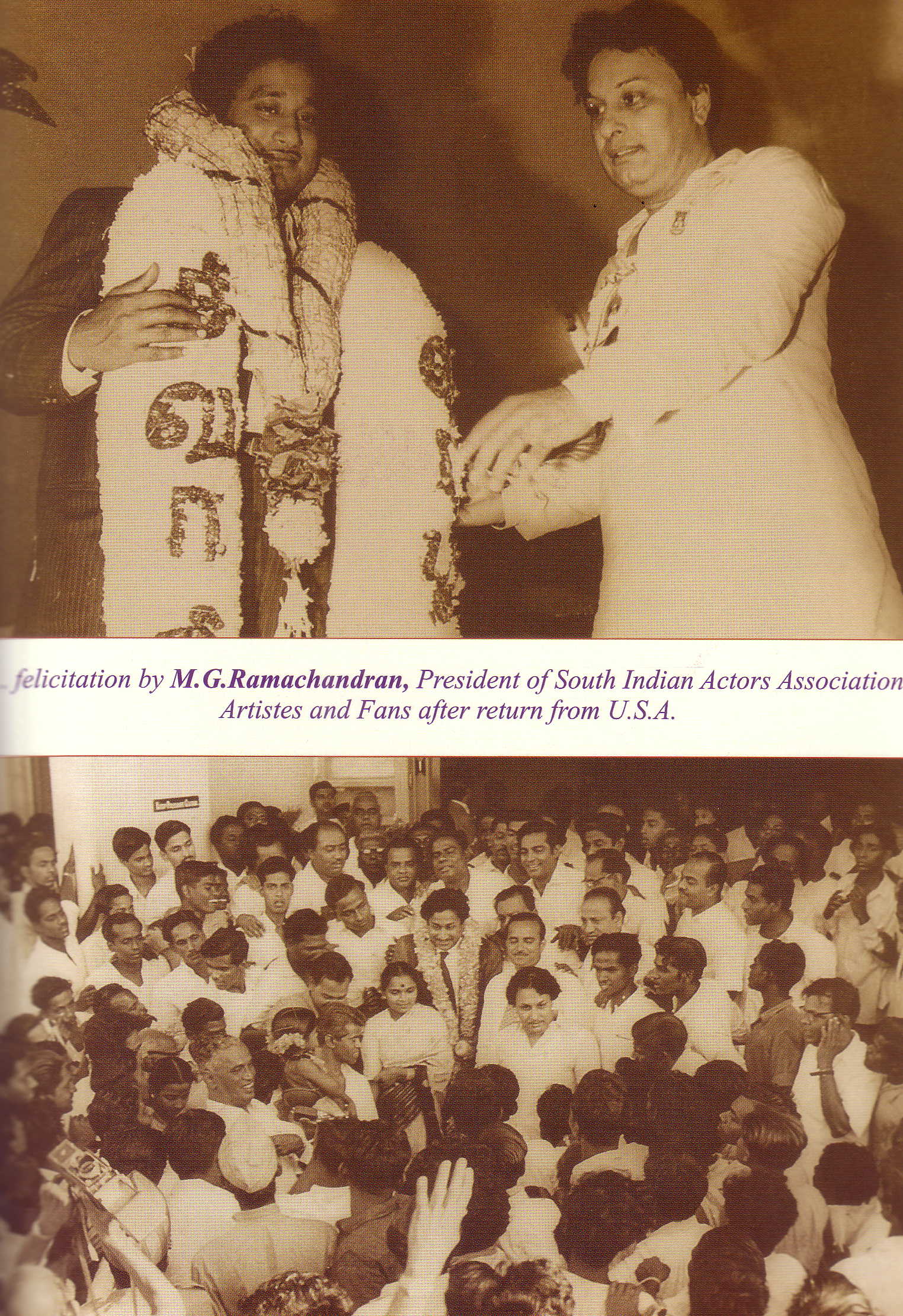

In addition to this, in 1962, when Sivaji Ganesan was chosen as a cultural ambassador by the American government for a three months visit, MGR then functioning as the President of the Nadigar Sangam, organized a send-off as well as welcome celebratory functions on behalf of the film community, despite the fact that Sivaji Ganesan had shifted his alliance to the Tamil National Party of E.V.K. Sampath and Congress Party.

MGR’s sincerity and dedication to the growth of Nadigar Sangam and welfare of his fellow peers, even after he became the Chief Minister of Tamil Nadu in late1970s, has been attested by Sivaji Ganesan himself. In his autobiography, Ganesan had reminisced as follows:

“Sri M.G. Ramachandran was the chief minister at that time. There was contemplation on whom to appoint as the President of the Association. Anna MGR advised the future members to request me to head the Association. ‘He is the only one who will take up the responsibility in a perfect manner. Sivaji is bound to refuse at first, but do not accept his refusal!’ said anna MGR. As per his advice, many people invited me and entreated me to head the Association. I relented only upon their insistence, and because my elder brother MGR wished me to take up the post.”

A critical version of MGR’s deeds as the chief functionary of Nadigar Sangam in 1960s had been presented by Karunanidhi in 1975. When this was written, MGR and Karunanidhi had become rivals in politics. Writing a chapter of his autobiography, with a non-sexual double entendre meaning as a title, ‘Nanayam Keddathu’ (Depreciation of Currency, or Bad Decorum) Karunanidhi pique on MGR was as follows: The regional DMK conference was scheduled to be held in Tiruchi-Tanjavur district on June 14-15, 1966. While he was planning to attend this conference, MGR’s deeds in supporting the candidacy of comedian Kaka Radhakrishnan (sponsored by the opposing parties) for the Presidential election of the Nadigar Sangam against his DMK party pal S.S. Rajendran (SSR) the same position, couldn’t allow Karunanidhi to participate in the Tiruchi conference.

Karunanidhi had written that he resented MGR’s campaign for Radhakrishnan over-riding decorum and party discipline. He did complain about MGR’s behavior to party leader Annadurai. As the outcome of that particular election turned in favor of SSR, Anna was disinterested in Karunanidhi’s complaint for the simple reason that the affair was merely a storm in a tea cup.

How can one interpret MGR’s behavior in this 1966 Presidential election for the Nadigar sangam? Why he preferred Kaka Radhakrishnan as opposed to SSR? Did he distrust the capabilities of SSR? The same SSR himself magnanimously, had failed to mention this particular election episode in his autobiography published last year. I had reviewed this book early this year [see, http://sangam.org/autobiography-actor-politician-s-s-rajendran/]. First, it may be implied that it might have been the intention of MGR to accommodate artistes belonging to all political parties, and not offer special privilege to DMK party members in the movie industry. But, Karunanidhi was not in favor in such open mindedness. Secondly, from MGR’s perspectives, both Kaka Radhakrishnan and SSR were his pals from stage-drama days, and MGR came to be acquainted with Radhakrishnan earlier than SSR. This was attested by Sivaji Ganesan in his autobiography. Thus, it might have been a matter of choice of heart rather than any indulgence of politics.

MGR Remembered Part 30 Sachi Sri Kantha

Cited Sources

Anon: Hema Malini tops in income-tax arrears. The Hindu (Madras), March 27, 1982, p.6.

Arurdoss. Cinema Nijamum Nizhalum, Arunthathi Nilayam, Chennai, 2001. (in Tamil)

Arurdhas. Naan Mugam Paartha Cinema Kannadigal, Kalaignan Pathippagam, Chennai, 2002. (in Tamil)

Arurdoss. Kottaiyum Kodambakkamum, Vikatan Pirasuram, Chennai, 2006 (in Tamil)

Arurdhas. Cinema Kalai KaLanchiyam, Manivasagar Pathippagam, Chennai, 2011 (in Tamil)

Arurdhas. MGR-Sivaji; En Iru Kangal, Manivasagar Pathippagam, Chennai, 2011 (in Tamil)

Arurdhas. Kodambakkathil Arupathu Aandukal, Manivasagar Pathippagam, Chennai, 2011 (in Tamil)

Arurdhas. Sivaji Venra Cinema Rajyam, Manivasagar Pathippagam, Chennai, 2012 (in Tamil)

Vyjayanthimala Bali: Bonding…A Memoir, Stella Publishers Ltd, New Delhi, 2007.

Eric Barnouw and S. Krishnaswamy: Indian Film, 2nd edition, Oxford University Press, New York, 1980, pp. 127-129, 143, 169, 177, 284.

Subrata Chattopadhyay: Black money in white coats: whither medical ethics? Indian Journal of Medical Ethics, 2008; 5(1): 20-21.

Narayani Ganesh: Eternal Romantic My Father Gemini Ganesan, Roli Books Ltd., New Delhi, 2011.

- Kirubakaran: Naan Aanaiyittaal… [Collection of MGR’s writings], Vikatan Pirasuram, 2nd ed., 2014, pp. 24-26. (in Tamil)

- Lakshmanan: Makkal Thilagam MGR, Vanathi Pathipagam, Chennai, 4th ed., 2002, pp. 13-15. (in Tamil)

T.S. Narayana Swamy: Autobiography of an Actor Sivaji Ganesan, English version, Sabita Radhakrishna, Sivaji Prabhu Charities Trust, Chennai, 2007, p. 214.

S.S. Rajendran: Nan Vantha Pathai, Akani Veliyeedu, Vandavasi, 2014 (in Tamil).

- Ravindar: Pon Mana Chemmal MGR, Vijaya Publications, Chennai, 2009, pp. 39-41. (in Tamil)

- Saravanan: AVM60- Cinema, Rarajan Pathipagam, Chennai, 2005, pp. 159-179. (in Tamil)

Sivakumar: Diary 1946-1975, Alliance Co, Chennai, 6th ed., 2012. (in Tamil)

Roopa Swaminathan: M. G. Ramachandran – Jewel of the Masses, Rupa & Co, New Delhi, 2002.

A correction: In fact, M.N. Rajam also acted in another hit movie of MGR -the first color movie produced in Tamil, i.e., ‘Alibabavum Narpathu Thirudarkalum’ (1956), produced by Modern Theatres. Her first appearance, in an MGR movie. This was the Tamil version of Arabian tale, Alibaba and 40 Thieves. Thus, M.N. Rajam had acted in 8 of MGR movies, between 1956 and 1966.

It is amazing to know the fact that in spite of living off on the goodwill of Tamil people, the current so called ‘Super-Stars’ pale in comparison with the one and only Super-Star MGR when it comes to philanthropy.