|

Comment by tamilnation.org, 20 March 2007 – at http://tamilnation.co/intframe/us/81mass_declaration.htm –

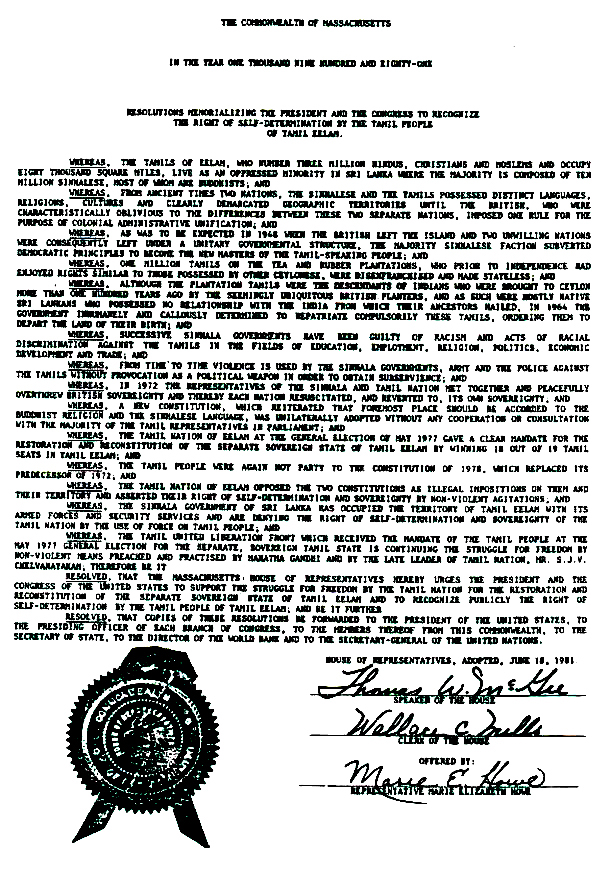

The Resolution passed by the Massachusetts House of Representatives on 18 June 1981 (more than twenty five years ago) makes it abundantly clear that the United States is not without an understanding of the justice of the Tamil Eelam struggle for freedom. What then has changed in the ensuing 25 years? Not much, if we recognise that countries do not have permanent friends but have permanent interests. Not much, if we recognise that the interests of a state are a function of the interests of groups which wield power within that state and ‘foreign policy is the external manifestation of domestic institutions, ideologies and other attributes of the polity’.

In 1981 at the time that the Massachusetts Resolution was passed, Indira Gandhi was building her influence within the Tamil militant movement. In 1998 at a Seminar in Switzerland, Jyotindra Nath Dixit Indian High Commissioner in Sri Lanka 1985 /89, Foreign Secretary in 1991/94 and National Security Adviser to the Prime Minister of India 2004/05 explainedIndira Gandhi and India’s Motivations in 1981-83 –

“…It would be relevant to analyse India’s motivations and actions in the larger perspective of the international and regional strategic environment, obtaining between 1950 and 1981 President Reagan was in power and the Soviet Union was going through the post Brezhnev uncertainties preceding Gorbachev’s arrival on the scene….The rise of Tamil militancy in Sri Lanka and the Jayawardene government’s serious apprehensions about this development were utilised by the US and Pakistan to create a politico-strategic pressure point against India, in the island’s strategically sensitive coast off the Peninsula of India. Jayawardene established substantive defensive and intelligence contacts with US, Pakistan and Israel. The Government of India was subject to internal centrifugal pressures in Punjab and Kashmir and portions of the north east during this time. Tamil militancy received support both from Tamil Nadu and from the Central Government not only as a response to the Sri Lankan Government’s military assertiveness against Sri Lankan Tamils, but also as a response to Jayawardene’s concrete and expanded military and intelligence cooperation with the United States, Israel and Pakistan.“

The Massachusetts Resolution of 1981 served to enhance US influence in the Tamil struggle (and build links with Tamil Eelam activists) in the same way as Indira Gandhi sought to enhance New Delhi’s influence on the Tamil struggle by encouraging Tamil Nadu rhetoric (and build links with Tamil Eelam activists). We will not be too far wrong if we conclude that at that time, Massachusetts was to Washington what Tamil Nadu was to New Delhi. It was also during this time period that in the US, Tamil rhetoric was allowed to flow freely atInternational Tamil Conferences.

At the same time US General Walters, a senior figure in the US strategic and intelligence establishment, was advising Sri Lanka and the US State Department proclaimed not long after the 1983 Genocide that “Sri Lanka is an open, working, multiparty democracy.”

It is understandable therefore that today the same strategic US interests in the Indian Ocean region lead to statements such as those made by U.S. Ambassador Robert Blake on 1 March 2007 that “Sri Lanka has in President Rajapakse a strong leader ” and by US Under Secretary of State Nicholas Burns on 21 November 2006 that “we hold the Tamil Tigers responsible for much of what has gone wrong in the country. We are not neutral in this respect.”

It is correct that the US has never been neutral. Unfortunately, the US (unlike Jyotindra Nath Dixit) has failed to be transparent about its own strategic interests and the motivations for its actions in relation to the conflict in the island of Sri Lanka. Unfortunate, because transparency is a first step towards an open evaluation of that which US may ‘perceive’ to be its strategic interests – after all, as we have said elsewhere, GNP is not necessarily a measure of wisdom. Sacked Sri Lanka Foreign Minister Mangala Samaraweera has ofcourse helped the Tamil people to further their understanding of international relations in this age of empire, when he said on 14 February 2007 –

“…. two days after the vote (on Israel), US Undersecretary of State Nicholas Burns telephoned me. The decision taken by us regarding the vote went a long way in building trust and strengthening US-Sri Lanka ties. Few days afterwards, at the Co-Chairs Meeting in Washington DC, Nicholas Burns expressed America’s fullest support to the Government of Sri Lanka in defeating the menace of LTTE terrorism. After the meeting he also held a press conference that was very encouraging to the Government and the people of Sri Lanka…”

Tamil cause consumes and divides brothers: Sri Lanka violence repels two while a third clings to hope

It started 30 years ago with a Somerville post office box  Sritharan Thillaiampalam, pictured with the Sri Lankan president Mahinda Rajapaksa , now thinks it might be wise to work with the government.registered to a grandiose name: the Embassy of Eelam. Three brothers from Sri Lanka who lived on Mount Vernon Street turned their dining room into an international headquarters for the struggle to create a homeland for the ethnic Tamil minority. It would be called Eelam.

Sritharan Thillaiampalam, pictured with the Sri Lankan president Mahinda Rajapaksa , now thinks it might be wise to work with the government.registered to a grandiose name: the Embassy of Eelam. Three brothers from Sri Lanka who lived on Mount Vernon Street turned their dining room into an international headquarters for the struggle to create a homeland for the ethnic Tamil minority. It would be called Eelam.

They lobbied state and local officials about the abuse of Tamils at the hands of the Sri Lankan government, prompting a Massachusetts boycott. Then-Governor Edward J. King announced his support for a Tamil homeland. Their lobbying boosted a Tamil rebel army fighting in Sri Lanka.

But since then, the rebels have killed thousands with suicide bombs, and were declared terrorists by the United States. The 25-year civil war, fueled in part by donations from local Tamils, has become one of the longest, bloodiest wars in the world, with more than 70,000 dead. And now, the rebels are on the verge of defeat.

That has left some of the roughly 2,000 Tamils in Boston grappling with the possibility that Eelam might never be achieved. They are also faced with the reality that their most cherished cause is now inextricably linked to a guerrilla war that pioneered the use of suicide bombings.

“We used to be the victims,” said Sritharan Thillaiampalam, a 69-year-old former Bank of Boston employee who helped spearhead the Eelam movement with his two brothers but is now disillusioned. “Later, a group of people started taking up arms, killing people, killing each other. That’s how it changed.”

But 2 miles away, his older brother, Sri Thillaiampalam, a 70-year-old former freight company assistant manager at Logan Airport, hasn’t given up on the dream of Eelam. He calls the Tigers “defenders” of the Tamils.

“My brother used to be my secretary general,” Sri lamented. “But now he has lost his way.”

There was a time when it seemed like the fate of Eelam lay on Mount Vernon Street. That was where the Thillaiampalam clan – five boys and five girls – all moved during the 1970s.

While many other Tamils in America avoided politics, fearing retribution against relatives back home, the Thillaiampalams were all in Massachusetts, so they threw themselves into the cause. As children, the brothers grew up in a time of relative peace in Sri Lanka, then known as Ceylon, an island off India’s coast roughly the size of West Virginia.

In the early 1940s, when they were boys, the island was a British colony. Sinhalese, who make up 74 percent of the population, were mostly Buddhists living in the south, while Tamils, who make up roughly 18 percent, were mostly Hindus in the north.

Living on the outskirts of Jaffna, a city populated by Tamils, the brothers played with the few Sinhalese classmates there and learned the Sinhalese language in school from Buddhist monks. But in 1956, shortly after the country gained independence, the Sri Lankan government declared Sinhalese to be the only official language, forcing many Tamils – including some Thillaiampalam relatives – out of government jobs. When Tamils protested, they were beaten by thugs.

At the time, Sritharan was a teenager fascinated by politics. He protested by defacing the Sinhalese words on the license plates of government buses – and landed in jail.

“My mother scolded me – ‘Why did you get involved?’ ” he recalled. In 1961, he joined a strike that shut down government offices.

A decade later, seeking to advance his career, Sritharan moved to Somerville to live with his older brother, Srikanthan, an engineer.

Sritharan got a job with the Bank of Boston, while his wife became an insurance analyst at John Hancock. Within a year, they bought their own Somerville three-decker.

“We always thought we would return to Sri Lanka,” he said. “But things kept getting worse.”

By the late 1970s, some of Sritharan’s friends in Sri Lanka formed a new nonviolent political party, the Tamil United Liberation Front, which demanded a separate state. In 1977, it became the largest opposition bloc in Sri Lanka’s Parliament. But its separatist views were swiftly outlawed.

Frustrated, many Tamils took up arms, joining a group of militants called the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam. (Eelam is a word in ancient Tamil literature that appears to refer to Sri Lanka.) Led by Velupillai Prabhakaran, an elusive guerrilla leader who inspires cultlike devotion, the militants killed 13 Sri Lankan soldiers in 1983. Riots and revenge killings followed, sparking a mass Tamil exodus.

Tamil refugees poured into Somerville, where they were hosted by the Thillaiampalams. Sritharan – pensive and serious – and Sri – gregarious and persistent – helped form a new group along with their older brother: the Eelam Tamil Association of America.

They opened a PO Box and got vanity license plates – Eelam One and Eelam Two. They lobbied their state representative, Marie Howe, an Irish-American who sympathized with their tales of marginalization and struggle. Every time Howe had a function, the whole Thillaiampalam clan would show up. (Howe did not return calls seeking comment.)

Howe persuaded Governor King to declare his support for Eelam and pushed through a divestment resolution modeled on the antiapartheid campaign. She introduced the brothers to Senator Edward M. Kennedy and John F. Kerry, a rising star in politics. Howe also helped get Somerville to declare Eelam Tamil Day, and to become a sister city to Trincomalee, a Sri Lankan port claimed by both Tamils and Sinhalese. A series of Somerville mayors, including Michael Capuano, raised a Tamil United Liberation Front flag over City Hall.

The brothers met then-House Speaker Thomas P. “Tip” O’Neill at a clambake fund-raiser and posed with him for a photo, creating the illusion that power brokers in Washington were dedicated to Eelam.

“It had a big impact back home,” Sritharan said. “They thought the US government was backing us fully. They thought we are millionaires here, giving money to Kerry and Kennedy, so that they were in our pockets.”

The brothers’ success shocked the Sri Lankan government, which complained to the State Department. But it impressed Tamil politicians, who began to make regular US visits to meet the brothers, who in turn introduced them to politicians and State Department officials, helping to block millions in foreign aid to Sri Lanka.

The brothers caught the attention of India, a regional superpower with a Tamil population of its own. They met Prime Minister Indira Gandhi, and her son and successor, Rajiv Gandhi, and begged for India’s intervention.

The brothers also met with Tiger militants in India. “We thought they were doing a great thing, sacrificing their lives to fight the Sri Lankan Army,” said Sritharan. “We called them our younger brothers. Through emissaries, [Tiger leader] Prabhakaran would say, ‘Send us money.’ ”

In 1984, Sri helped orchestrate a successful meeting between Indira Ghandi and Tamil militants who were seeking weapons and training from India, including Prabhakaran.

“They looked at me as someone who would make the world move,” Sri said. “They asked me to be part of the team. I said no. I had to draw a line, where I get off. I’m not getting involved in fighting.”

In 1986, the brothers held a conference in New York and invited militants to participate, according to Sritharan.

But the Tigers refused, sending a letter that read like a warning: “We are the only representatives of the Tamils. . . . We are fighting in a military battle and we need financial support. If you want to achieve Eelam, you have to help us.”

By 1987, the brothers’ work seemed to be coming to fruition. India sent peacekeepers and prodded the Sri Lankan government to agree to set up a semiautonomous regional council in the Tamil north.

But the Tigers refused to accept anything short of a separate state. They attacked the Indian peacekeepers and later assassinated Rajiv Gandhi, who had sent them. They killed moderate Tamil politicians who tried to join the council.

They shot the Tamil leader who had traveled to Boston to meet Ed King. They killed Neelan Tiruchelvam, a Harvard-educated lawyer who advocated federalism instead of Eelam. They killed Sri Lanka’s foreign minister, a Tamil, and the head of the Tamil United Liberation Front, one of Sritharan’s best friends. Tiger suicide bombers, who pioneered the technique before it became common in the Middle East, also killed scores of Sinhalese civilians.

The violence prompted Srikanthan, the eldest Thillaiampalam brother, to give up activism. Now living in Winchester, he did not return a call seeking comment.

Sritharan, too, had a radical change of heart. At his dining room table, surrounded by newspaper clippings and photos of himself with famous people who are now dead, he explained why he stopped lobbying for Eelam.

“Everybody was being killed by the Tigers,” he said. “How can you complain to the State Department – ‘We are the victims. Please save us?’ ”

Now, he believes Tamils will have a better future negotiating with the Sri Lankan government for autonomy under a federal system. He supports Douglas Devananda, a former Tamil militant serving in Sri Lanka’s Cabinet. Recently, he traveled to the United Nations to meet Sri Lanka’s president.

“Today, I am a traitor,” he said, describing how he believes other Tamils in Boston see him.

Across town, at another dining room table piled with copies of the same photographs and newspaper clippings, Sri says he doesn’t blame his brothers but continues lobbying alone.

“I tell the State Department: ‘Look at me. I am like a Jew. Look at Eelam. It is like Israel,’ ” he said. “I dedicate my life. This is all I do.”

Sri said he was shaken by the suicide bombings, but that the Tigers “only do these things when they have to.”

In 1998, the US government designated the Tigers a terrorist organization. After the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks, people began to shy away from the Tamil cause. The US government cracked down on Tiger fund-raising.

The Eelam Tamil Association faded away, replaced by the Boston Thamil Association, which members say is solely for organizing cultural festivals and language training.

But it has been embroiled in controversy over terrorism. After a tsunami struck Sri Lanka in 2004, the Boston Thamil Association raised more than $200,000 for victims. But it gave $12,245 to the Tamil Rehabilitation Organization, or TRO, a charity that the US Treasury banned as a Tiger front in 2007.

Surenthira Thurairatnam, president of the Boston Thamil Association, insists that TRO is a genuine charity. “The Tamils know that TRO is the only organization in the region helping the Tamil civilians,” he said.

Sri, also a member of the Boston Thamil Association, said the accusations against the TRO were “trumped up.”

“None of us that gave to the TRO had any intention of buying bullets,” he said. “I’m struggling to pay my bills. How can I afford to buy a bullet?”

But according to documents filed in a 2007 criminal case against an alleged Tiger fund-raiser in New York, the Tigers had instructed their proxies in the United States to “collect monthly donations from the Tamil communities,” funneling the money through the TRO. Martin Collacott, a former Canadian ambassador to Sri Lanka, said that Tamils abroad send millions of dollars each year to fund the war, sometimes unwillingly. In Canada, home to the largest number of Tamil expatriates of any country, “heavy pressure is put on each Tamil family to contribute,” he said.

Collacott said Tiger fronts control Tamil language newspapers, radio stations, and resettlement services in Canada. Those who speak out against the Tigers or refuse to donate risk social ostracism and physical attack.

Last year, fund-raisers from Canada knocked on Sritharan’s door in Winchester.

“They said, ‘We need helicopters, guns,’ ” he recalled. “They said, ‘This is the final push.’ ”

When he told them he had no money, they produced paperwork for a bank loan and asked him to sign, saying, ‘When Eelam comes, we’ll settle it.’ ”

“They know that I am against them,” he said, adding that he did not sign. “But they tried it anyway.”

But his brother insists that he is not aware of any Tiger fund-raising here. Still, Sri got a visit from the FBI a few years ago, asking him whether he was involved.

“They know I am in the Eelam movement,” Sri said. “Tigers are defending my people. I respect them. But I’m not funding them.”

Some Tamils maintain that the Tigers do not really use suicide attacks. Others say the Tigers are the lesser of two evils – and the only hope for self-government and respect.

“I am not in any way supporting violence, but if there were no Tigers there would have been a lot of other things – the taking of land and the lives of innocent people,” said Thurairatnam, the head of the Boston Thamil Association.

But today, the Tigers are on the verge of defeat. After a 2002 cease-fire broke down, Sri Lanka launched a major offensive, recently reclaiming all but 8 square miles of the once-vast area the Tigers had controlled. Now, Sri Lanka is poised to wipe out Prabhakaran and the last of his fighters. The only thing stopping them are tens of thousands of civilians mixed in with the rebels. Some news reports say the Tigers are using them as human shields, shooting those who try to leave. Tamil media says Sri Lanka’s military is perpetrating a genocide.

The situation has sparked a new generation of Tamil activism, State House rallies and petitions for a cease-fire. More than a dozen Tamils have set themselves on fire in India and elsewhere. Tamil students across the United States, including a Winchester teen, went on a hunger strike, earning her an invitation to Washington to meet Kerry, now chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee.

But this time, Tamils are having a hard time generating support. “We are crying loud, but it seems like nobody is listening,” said Thurairatnam.

In Winchester, Sritharan shakes his head at the burst of activism. He believes the war will end soon – “it’s a matter of hours and days” – bringing a brighter future for Tamils. He believes those who are holding out for Eelam will scatter and disappear.

But his brother stays at the computer night and day, sending e-mails and organizing protests. Despite the news, he does not believe that the Tigers will be defeated.

“This is a people’s movement,” Sri said. “They are not going to walk away and vanish in thin air.”

At the time, Sritharan was a teenager fascinated by politics. He protested by defacing the Sinhalese words on the license plates of government buses – and landed in jail.

My mother scolded me – ‘Why did you get involved?’ ” he recalled. In 1961, he joined a strike that shut down government offices.

A decade later, seeking to advance his career, Sritharan moved to Somerville to live with his older brother, Srikanthan, an engineer. Sritharan got a job with the Bank of Boston, while his wife became an insurance analyst at John Hancock. Within a year, they bought their own Somerville three-decker.

“We always thought we would return to Sri Lanka,” he said. “But things kept getting worse.”

By the late 1970s, some of Sritharan’s friends in Sri Lanka formed a new nonviolent political party, the Tamil United Liberation Front, which demanded a separate state. In 1977, it became the largest opposition bloc in Sri Lanka’s Parliament. But its separatist views were swiftly outlawed.

Frustrated, many Tamils took up arms, joining a group of militants called the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam. (Eelam is a word in ancient Tamil literature that appears to refer to Sri Lanka.) Led by Velupillai Prabhakaran, an elusive guerrilla leader who inspires cultlike devotion, the militants killed 13 Sri Lankan soldiers in 1983. Riots and revenge killings followed, sparking a mass Tamil exodus.

Tamil refugees poured into Somerville, where they were hosted by the Thillaiampalams. Sritharan – pensive and serious – and Sri – gregarious and persistent – helped form a new group along with their older brother: the Eelam Tamil Association of America.

They opened a PO Box and got vanity license plates – Eelam One and Eelam Two. They lobbied their state representative, Marie Howe, an Irish-American who sympathized with their tales of marginalization and struggle. Every time Howe had a function, the whole Thillaiampalam clan would show up. (Howe did not return calls seeking comment.)

Howe persuaded Governor King to declare his support for Eelam and pushed through a divestment resolution modeled on the antiapartheid campaign. She introduced the brothers to Senator Edward M. Kennedy and John F. Kerry, a rising star in politics. Howe also helped get Somerville to declare Eelam Tamil Day, and to become a sister city to Trincomalee, a Sri Lankan port claimed by both Tamils and Sinhalese. A series of Somerville mayors, including Michael Capuano, raised a Tamil United Liberation Front flag over City Hall. The brothers met then-House Speaker Thomas P. “Tip” O’Neill at a clambake fund-raiser and posed with him for a photo, creating the illusion that power brokers in Washington were dedicated to Eelam.

“It had a big impact back home,” Sritharan said. “They thought the US government was backing us fully. They thought we are millionaires here, giving money to Kerry and Kennedy, so that they were in our pockets.”Continued…

The brothers’ success shocked the Sri Lankan government, which complained to the State Department. But it impressed Tamil politicians, who began to make regular US visits to meet the brothers, who in turn introduced them to politicians and State Department officials, helping to block millions in foreign aid to Sri Lanka.

The brothers caught the attention of India, a regional superpower with a Tamil population of its own. They met Prime Minister Indira Gandhi, and her son and successor, Rajiv Gandhi, and begged for India’s intervention.

The brothers also met with Tiger militants in India.

“We thought they were doing a great thing, sacrificing their lives to fight the Sri Lankan Army,” said Sritharan. “We called them our younger brothers. Through emissaries, [Tiger leader] Prabhakaran would say, ‘Send us money.’ ”

In 1984, Sri helped orchestrate a successful meeting between Indira Ghandi and Tamil militants who were seeking weapons and training from India, including Prabhakaran.

“They looked at me as someone who would make the world move,” Sri said. “They asked me to be part of the team. I said no. I had to draw a line, where I get off. I’m not getting involved in fighting.”

In 1986, the brothers held a conference in New York and invited militants to participate, according to Sritharan.

But the Tigers refused, sending a letter that read like a warning: “We are the only representatives of the Tamils. . . . We are fighting in a military battle and we need financial support. If you want to achieve Eelam, you have to help us.”

By 1987, the brothers’ work seemed to be coming to fruition. India sent peacekeepers and prodded the Sri Lankan government to agree to set up a semiautonomous regional council in the Tamil north.

But the Tigers refused to accept anything short of a separate state. They attacked the Indian peacekeepers and later assassinated Rajiv Gandhi, who had sent them. They killed moderate Tamil politicians who tried to join the council.

They shot the Tamil leader who had traveled to Boston to meet Ed King. They killed Neelan Tiruchelvam, a Harvard-educated lawyer who advocated federalism instead of Eelam. They killed Sri Lanka’s foreign minister, a Tamil, and the head of the Tamil United Liberation Front, one of Sritharan’s best friends. Tiger suicide bombers, who pioneered the technique before it became common in the Middle East, also killed scores of Sinhalese civilians.

The violence prompted Srikanthan, the eldest Thillaiampalam brother, to give up activism. Now living in Winchester, he did not return a call seeking comment.

Sritharan, too, had a radical change of heart. At his dining room table, surrounded by newspaper clippings and photos of himself with famous people who are now dead, he explained why he stopped lobbying for Eelam.

“Everybody was being killed by the Tigers,” he said. “How can you complain to the State Department ‘We are the victims. Please save us?’ ”

Now, he believes Tamils will have a better future negotiating with the Sri Lankan government for autonomy under a federal system. He supports Douglas Devananda, a former Tamil militant serving in Sri Lanka’s Cabinet. Recently, he traveled to the United Nations to meet Sri Lanka’s president.

“Today, I am a traitor,” he said, describing how he believes other Tamils in Boston see him.

Across town, at another dining room table piled with copies of the same photographs and newspaper clippings, Sri says he doesn’t blame his brothers but continues lobbying alone.

“I tell the State Department: ‘Look at me. I am like a Jew. Look at Eelam. It is like Israel,’ ” he said. “I dedicate my life. This is all I do.”

Sri said he was shaken by the suicide bombings, but that the Tigers “only do these things when they have to.”

In 1998, the US government designated the Tigers a terrorist organization. After the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks, people began to shy away from the Tamil cause. The US government cracked down on Tiger fund-raising.

The Eelam Tamil Association faded away, replaced by the Boston Thamil Association, which members say is solely for organizing cultural festivals and language training.

But it has been embroiled in controversy over terrorism. After a tsunami struck Sri Lanka in 2004, the Boston Thamil Association raised more than $200,000 for victims. But it gave $12,245 to the Tamil Rehabilitation Organization, or TRO, a charity that the US Treasury banned as a Tiger front in 2007.

Surenthira Thurairatnam, president of the Boston Thamil Association, insists that TRO is a genuine charity.

“The Tamils know that TRO is the only organization in the region helping the Tamil civilians,” he said.

Sri, also a member of the Boston Thamil Association, said the accusations against the TRO were “trumped up.”

“None of us that gave to the TRO had any intention of buying bullets,” he said. “I’m struggling to pay my bills. How can I afford to buy a bullet?”

But according to documents filed in a 2007 criminal case against an alleged Tiger fund-raiser in New York, the Tigers had instructed their proxies in the United States to “collect monthly donations from the Tamil communities,” funneling the money through the TRO. Martin Collacott, a former Canadian ambassador to Sri Lanka, said that Tamils abroad send millions of dollars each year to fund the war, sometimes unwillingly. In Canada, home to the largest number of Tamil expatriates of any country, “heavy pressure is put on each Tamil family to contribute,” he said.

Collacott said Tiger fronts control Tamil language newspapers, radio stations, and resettlement services in Canada. Those who speak out against the Tigers or refuse to donate risk social ostracism and physical attack.

Last year, fund-raisers from Canada knocked on Sritharan’s door in Winchester.

“They said, ‘We need helicopters, guns,’ ” he recalled. “They said, ‘This is the final push.’ ”

When he told them he had no money, they produced paperwork for a bank loan and asked him to sign, saying, ‘When Eelam comes, we’ll settle it.’ ”

“They know that I am against them,” he said, adding that he did not sign. “But they tried it anyway.”

But his brother insists that he is not aware of any Tiger fund-raising here. Still, Sri got a visit from the FBI a few years ago, asking him whether he was involved.

“They know I am in the Eelam movement,” Sri said. “Tigers are defending my people. I respect them. But I’m not funding them.” Some Tamils maintain that the Tigers do not really use suicide attacks. Others say the Tigers are the lesser of two evils – and the only hope for self-government and respect.

“I am not in any way supporting violence, but if there were no Tigers there would have been a lot of other things – the taking of land and the lives of innocent people,” said Thurairatnam, the head of the Boston Thamil Association.

But today, the Tigers are on the verge of defeat. After a 2002 cease-fire broke down, Sri Lanka launched a major offensive, recently reclaiming all but 8 square miles of the once-vast area the Tigers had controlled. Now, Sri Lanka is poised to wipe out Prabhakaran and the last of his fighters. The only thing stopping them are tens of thousands of civilians mixed in with the rebels. Some news reports say the Tigers are using them as human shields, shooting those who try to leave. Tamil media says Sri Lanka’s military is perpetrating a genocide.

The situation has sparked a new generation of Tamil activism, State House rallies and petitions for a cease-fire. More than a dozen Tamils have set themselves on fire in India and elsewhere. Tamil students across the United States, including a Winchester teen, went on a hunger strike, earning her an invitation to Washington to meet Kerry, now chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee.

But this time, Tamils are having a hard time generating support.

“We are crying loud, but it seems like nobody is listening,” said Thurairatnam.

In Winchester, Sritharan shakes his head at the burst of activism. He believes the war will end soon – “it’s a matter of hours and days” – bringing a brighter future for Tamils. He believes those who are holding out for Eelam will scatter and disappear.

But his brother stays at the computer night and day, sending e-mails and organizing protests. Despite the news, he does not believe that the Tigers will be defeated.

“This is a people’s movement,” Sri said. “They are not going to walk away and vanish in thin air.”

The brothers’ success shocked the Sri Lankan government, which complained to the State Department. But it impressed Tamil politicians, who began to make regular US visits to meet the brothers, who in turn introduced them to politicians and State Department officials, helping to block millions in foreign aid to Sri Lanka.

The brothers caught the attention of India, a regional superpower with a Tamil population of its own. They met Prime Minister Indira Gandhi, and her son and successor, Rajiv Gandhi, and begged for India’s intervention.

The brothers also met with Tiger militants in India. “We thought they were doing a great thing, sacrificing their lives to fight the Sri Lankan Army,” said Sritharan. “We called them our younger brothers. Through emissaries, [Tiger leader] Prabhakaran would say, ‘Send us money.’ ”

In 1984, Sri helped orchestrate a successful meeting between Indira Ghandi and Tamil militants who were seeking weapons and training from India, including Prabhakaran.

“They looked at me as someone who would make the world move,” Sri said. “They asked me to be part of the team. I said no. I had to draw a line, where I get off. I’m not getting involved in fighting.”

In 1986, the brothers held a conference in New York and invited militants to participate, according to Sritharan.

But the Tigers refused, sending a letter that read like a warning: “We are the only representatives of the Tamils. . . . We are fighting in a military battle and we need financial support. If you want to achieve Eelam, you have to help us.”

By 1987, the brothers’ work seemed to be coming to fruition. India sent peacekeepers and prodded the Sri Lankan government to agree to set up a semiautonomous regional council in the Tamil north.

But the Tigers refused to accept anything short of a separate state. They attacked the Indian peacekeepers and later assassinated Rajiv Gandhi, who had sent them. They killed moderate Tamil politicians who tried to join the council.

They shot the Tamil leader who had traveled to Boston to meet Ed King. They killed Neelan Tiruchelvam, a Harvard-educated lawyer who advocated federalism instead of Eelam. They killed Sri Lanka’s foreign minister, a Tamil, and the head of the Tamil United Liberation Front, one of Sritharan’s best friends. Tiger suicide bombers, who pioneered the technique before it became common in the Middle East, also killed scores of Sinhalese civilians.

The violence prompted Srikanthan, the eldest Thillaiampalam brother, to give up activism. Now living in Winchester, he did not return a call seeking comment.

Sritharan, too, had a radical change of heart. At his dining room table, surrounded by newspaper clippings and photos of himself with famous people who are now dead, he explained why he stopped lobbying for Eelam.

Everybody was being killed by the Tigers,” he said. “How can you complain to the State Department ‘We are the victims. Please save us?’ ”

Now, he believes Tamils will have a better future negotiating with the Sri Lankan government for autonomy under a federal system. He supports Douglas Devananda, a former Tamil militant serving in Sri Lanka’s Cabinet. Recently, he traveled to the United Nations to meet Sri Lanka’s president.

“Today, I am a traitor,” he said, describing how he believes other Tamils in Boston see him.

Across town, at another dining room table piled with copies of the same photographs and newspaper clippings, Sri says he doesn’t blame his brothers but continues lobbying alone.

“I tell the State Department: ‘Look at me. I am like a Jew. Look at Eelam. It is like Israel,’ ” he said. “I dedicate my life. This is all I do.”

Sri said he was shaken by the suicide bombings, but that the Tigers “only do these things when they have to.”

In 1998, the US government designated the Tigers a terrorist organization. After the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks, people began to shy away from the Tamil cause. The US government cracked down on Tiger fund-raising.

The Eelam Tamil Association faded away, replaced by the Boston Thamil Association, which members say is solely for organizing cultural festivals and language training.

But it has been embroiled in controversy over terrorism. After a tsunami struck Sri Lanka in 2004, the Boston Thamil Association raised more than $200,000 for victims. But it gave $12,245 to the Tamil Rehabilitation Organization, or TRO, a charity that the US Treasury banned as a Tiger front in 2007.

Surenthira Thurairatnam, president of the Boston Thamil Association, insists that TRO is a genuine charity.

“The Tamils know that TRO is the only organization in the region helping the Tamil civilians,” he said.

Sri, also a member of the Boston Thamil Association, said the accusations against the TRO were “trumped up.”

“None of us that gave to the TRO had any intention of buying bullets,” he said. “I’m struggling to pay my bills. How can I afford to buy a bullet?”

But according to documents filed in a 2007 criminal case against an alleged Tiger fund-raiser in New York, the Tigers had instructed their proxies in the United States to “collect monthly donations from the Tamil communities,” funneling the money through the TRO.

Martin Collacott, a former Canadian ambassador to Sri Lanka, said that Tamils abroad send millions of dollars each year to fund the war, sometimes unwillingly. In Canada, home to the largest number of Tamil expatriates of any country, “heavy pressure is put on each Tamil family to contribute,” he said.

Collacott said Tiger fronts control Tamil language newspapers, radio stations, and resettlement services in Canada. Those who speak out against the Tigers or refuse to donate risk social ostracism and physical attack.

Last year, fund-raisers from Canada knocked on Sritharan’s door in Winchester.

“They said, ‘We need helicopters, guns,’ ” he recalled. “They said, ‘This is the final push.’ ”

When he told them he had no money, they produced paperwork for a bank loan and asked him to sign, saying, ‘When Eelam comes, we’ll settle it.’ ”

“They know that I am against them,” he said, adding that he did not sign. “But they tried it anyway.”

But his brother insists that he is not aware of any Tiger fund-raising here. Still, Sri got a visit from the FBI a few years ago, asking him whether he was involved.

“They know I am in the Eelam movement,” Sri said. “Tigers are defending my people. I respect them. But I’m not funding them.”

Some Tamils maintain that the Tigers do not really use suicide attacks. Others say the Tigers are the lesser of two evils – and the only hope for self-government and respect.

“I am not in any way supporting violence, but if there were no Tigers there would have been a lot of other things – the taking of land and the lives of innocent people,” said Thurairatnam, the head of the Boston Thamil Association.

But today, the Tigers are on the verge of defeat. After a 2002 cease-fire broke down, Sri Lanka launched a major offensive, recently reclaiming all but 8 square miles of the once-vast area the Tigers had controlled. Now, Sri Lanka is poised to wipe out Prabhakaran and the last of his fighters.

The only thing stopping them are tens of thousands of civilians mixed in with the rebels. Some news reports say the Tigers are using them as human shields, shooting those who try to leave. Tamil media says Sri Lanka’s military is perpetrating a genocide.

The situation has sparked a new generation of Tamil activism, State House rallies and petitions for a cease-fire. More than a dozen Tamils have set themselves on fire in India and elsewhere. Tamil students across the United States, including a Winchester teen, went on a hunger strike, earning her an invitation to Washington to meet Kerry, now chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee.

But this time, Tamils are having a hard time generating support. “We are crying loud, but it seems like nobody is listening,” said Thurairatnam.

In Winchester, Sritharan shakes his head at the burst of activism. He believes the war will end soon -“it’s a matter of hours and days” – bringing a brighter future for Tamils. He believes those who are holding out for Eelam will scatter and disappear.

But his brother stays at the computer night and day, sending e-mails and organizing protests. Despite the news, he does not believe that the Tigers will be defeated.

“This is a people’s movement,” Sri said. “They are not going to walk away and vanish in thin air.”

Courtesy: Tamil cause consumes and divides brothers

– Asian Tribune –