EARLY IN DECEMBER LAST YEAR, Kadiramalai Loganathan’s father succumbed to a long illness.

The funeral exacted a heavy price, and to recoup it the fisherman had little choice but to quickly return to sea.

On the night of 16 December, barely a week after his loss, Loganathan set out, with one other fisherman, from Karainagar, a small island off the Jaffna peninsula in north Sri Lanka, in his small fibre-glass boat with a modest engine.

Just a few kilometres out, as he waited after casting his net, Loganathan spotted a big, mechanised boat—a trawler. “Before I knew it, the boat started pulling away my net,” he told me.

He chased after the trawler as fast as he could to try and save the net, his biggest investment. He had borrowed 2 lakh Sri Lankan rupees to buy it—about 90,000 Indian rupees or $1,350—and had hardly started repaying the loan.

But his boat was no match for the larger vessel. “I shined the lights up to signal them to stop,” Loganathan said. The men on the trawler shouted back in Tamil, “Annachi”—elder brother—“don’t show any lights. The navy will get us.”

Loganathan recognised their Tamil dialect, different from the one spoken in north Sri Lanka, from his days as a refugee in Tamil Nadu, in India, during the Sri Lankan Civil War.

Loganathan got his net back, but it was in tatters and could not be salvaged.

He took out another loan to buy a second-hand net, which he has been using ever since.

He makes ends meet with support from his wife, Rathneswary, who helps with his work on shore in addition to keeping house.

The couple lives with the youngest of their three daughters, who is still in school.

I met Loganathan on a visit to Karainagar in June.

On a Tuesday morning, I watched the daily auction at the village’s fishermen’s cooperative—recognised as the best run cooperative in Jaffna district by a federation of 117 of them.

A man called out bids from a cement platform, with little modulation, while a small catch of silvery fish lay on an empty sack near his feet.

“500… 510… 550… 550… 580… 580… 580…” He paused after each number to survey the room for a higher bid. 580 was it. The catch was dragged away, making way for another.

Baskets of fish went into and out of the room, with a small percentage of each catch going into a bucket as the cooperative’s share. Two cats walked quietly about.

The place looked as I remembered it from a visit in 2014, except that back then there were at least twice as many fishermen, and a lot more fish in their baskets.

Even two years ago, it was hard to find a fisherman who took home a decent profit.

Now, it seemed impossible. Loganathan’s catch fetched 1,400 rupees that day, but he had spent 600 rupees on fuel for his boat, and had to pay 1,000 rupees to a fisherman he had hired to work with him.

“So it’s a loss of 200,” the lean 48-year-old said. “This is how it has been for a while now.” About 200,000 people in Sri Lanka’s predominantly Tamil Northern Province—about a fifth of its entire population—depend on the sea for a living.

For much of the two-and-a-half decades that the Sri Lankan government battled the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam, who wanted a separate state for Sri Lanka’s Tamil minority in the island’s north and east, fishermen were barred from the waters along the country’s north coast.

The war caused massive damage to property, displaced huge numbers of people, and is estimated to have claimed nearly 100,000 lives.

After it ended, in 2009, fishermen in north Sri Lanka started piecing their lives back together, buying small boats and returning to sea—only to find that trawlers from Tamil Nadu were ravaging their waters.

Catches were significantly smaller than before and Sri Lankan fishermen, almost all of whom practise small-scale, non-mechanised fishing, now worked in perpetual fear of losing their nets, as Loganathan had. Loganathan had fled to Tamil Nadu in the mid 1990s, and spent about eight years in refugee camps there.

He returned in late 2004, during a lull in the fighting, only to see Karainagar devastated by the Indian Ocean tsunami. But now, he said, “I feel I was better off during the war or tsunami.

That is how pathetic my current situation is.” “The people of Tamil Nadu have always stood with us, particularly during the war,” Loganathan continued. “No one in Sri Lanka immolated themselves for our cause, only people in Tamil Nadu did. We realise that and we are grateful. But they should let us fish.”

S SELLACHI DID NOT HAVE MUCH TIME to spare on the morning that we met.

An annual 45-day ban on mechanised fishing, enforced in Tamil Nadu since 2001 to allow fish to breed, was coming to an end in less than a week, on 29 May.

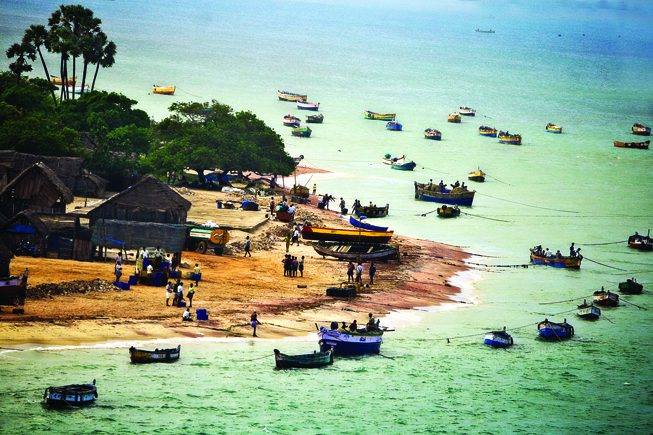

She had hired workers to repair her boat in preparation, and was supervising them. Sellachi’s boat was one of a long row of trawlers hauled out of the water and arrayed along the coast in the town of Jagadapattinam, in Tamil Nadu’s Pudukkottai district.

All of them were being readied for the following week.

The state has roughly 4,500 registered trawlers, at least 2,500 of which fish in the Palk Strait—a narrow stretch of sea separating India and Sri Lanka, beginning just north of the Jaffna peninsula and extending about 100 kilometres at its widest.

The maritime boundary between India and Sri Lanka, mutually agreed upon in the mid 1970s, runs more or less through the middle of it, and each country has sovereignty over the waters and resources on its side.

India has been encouraging mechanised fishing for decades, ever since a joint project with the Norwegian government that pumped millions of dollars into modernising the country’s fishing fleet between the 1950s and the early 1970s.

Through those decades and after, thousands of people invested in trawlers, lured by the promise of high profits.

Trawlers bring in catches numerous times as large as those of unmechanised vessels—which in India still outnumber trawlers many fold. Trawling presently accounts for 55 percent of the country’s seafood production, and the corresponding share for Tamil Nadu is higher still.

The state exported a total of 93,477 tonnes of seafood in the 2015 fiscal year, earning Rs5,308 crore, or about $830 million.

Indian seafood exports in the last fiscal year totalled a record one million tonnes, and earned $5.5 billion in foreign exchange. As the number of Indian trawlers has grown, so has the intensity of fishing in the waters closest to the country’s coast. This has led to overfishing and depleted catches. So Indian trawlers have been pushing farther out, into fresher, more fruitful waters.

In the Palk Strait—which is particularly tempting for its bounty of prawn, in high demand on the international market—Indian vessels regularly breach the maritime boundary to fish on the Sri Lankan side, which has remained relatively unexploited by fishermen from north Sri Lanka, with their smaller vessels and less intensive fishing techniques.

Sellachi watched two young men repairing a wooden plank that was soon to be reinstalled on the boat. In between this, she turned towards the vessel, where S Sriram, the youngest of her four sons, was getting some electrical work done.

Sriram, aged 18, had just completed a three-year course in mechanical engineering in a nearby town, and was helping out while on a break before job-placement interviews.

Until a couple of years ago, he used to go out to sea with Sellachi’s hired crews.

“You need at least five or six people to go on a trawler boat,” she explained, “and we would send him sometimes. But not anymore. He faced enough problems, and he has not forgiven me for that.”

Clad in black shorts and a yellow T-shirt heavily stained with grease, Sriram jumped with ease off the boat deck some three metres above us, and led me to a shaded spot nearby to tell his story.

About a year and a half ago, the boat was fishing near Katchatheevu, an island that lies across the maritime boundary, when it was intercepted by the Sri Lankan navy. “They pelted us with stones, and arrested us,” he said.

Sriram spent three months in detention in Sri Lanka—about a month in prison, and the rest in a children’s home in Jaffna city.

At the home, he joined five other Indian youngsters detained on charges of illegal fishing.

“The food was bad in the jail, but okay at the children’s home,” he said. After a brief pause, he added, “I will never go back to sea.”

THROUGH THE MIDDLE OF THE LAST CENTURY, movement was freer on the Palk Strait, and fishermen from both sides comfortably shared its rich waters.

NV Subramanian, a leader of a fishermen’s cooperative in Jaffna, told me how, in the early 1970s, he used to take boats to the town of Rameswaram, on the other side of the strait, to watch Tamil films.

“We would set out by noon, reach India by six in the evening, watch the show and leave by ten,” he said.

The war changed things completely, and hit Sri Lankan fishermen especially hard. In the early days of the conflict, numerous Tamil militant groups operated in north Sri Lanka and had bases in Tamil Nadu.

Fishermen were ideally placed to smuggle fighters and supplies across, and many of them developed strong ties to these groups, including the Tigers.

As the war intensified and the Tigers consolidated control over the insurgency, the Sri Lankan navy began battling them for control of the coast and sea.

Government forces treated fishermen from the north of the island with particular suspicion.

The association between the Tigers and the fishing community in the public mind was strengthened by the fact that the rebels’ leader, Velupillai Prabhakaran, came from a traditional fishing caste.

But the fishing community in north Sri Lanka was hardly a uniform whole, and its interactions with the Tigers were shaped by coercion as well as cooperation, and by internal fissures of class and caste.

The rebels did not hesitate to overlook the community’s interests in favour of their own.

Fishermen were kept from the sea at various points during the conflict, sometimes by the navy, sometimes by the Tigers’ naval wing, and sometimes by both.

By the time the war ended, trawlers dominated the Indian side of the maritime boundary, and soon they brought trouble into Sri Lankan waters.

Trawling involves dragging large nets through the sea, either in the middle of the water column or along the seabed.

Particularly when practised intensively, it has severe ecological effects.

Environmentalists complain that it causes overfishing, and indiscriminately scoops out young fishes and other creatures that the fishermen are not targeting.

Bottom trawling also disrupts the marine ecology by damaging the seabed and throwing up large quantities of sediment.