We Are Here Because You Were With Us

by Virou Srilangarajah, ‘Ceasefire,’ UK, February 4, 2018

That he was still alive at the time, though in comparative retirement, makes that neglect even sadder.” So wrote Ambalavaner Sivanandan in 1980, commenting on the lack of acknowledgement by black political movements of the 1960s in the United States of the immense contribution and influence of Paul Robeson. Sivanandan pointed out that although they rightly honoured Martin Luther King and Malcolm X, they failed to acknowledge the struggles and sacrifices of Robeson that preceded them.

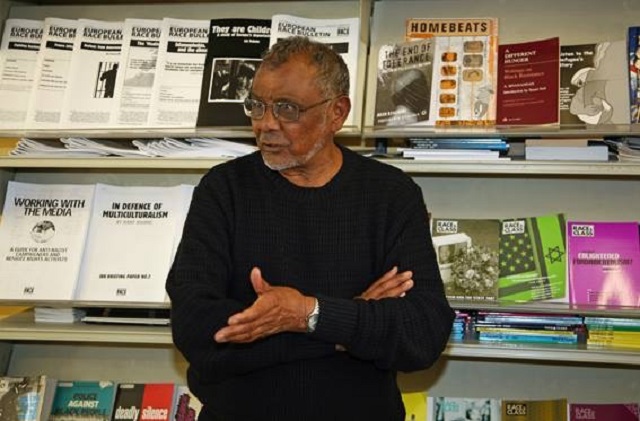

These words echo the sentiment felt by activists, scholars and communities involved in the anti-racist movement in Britain with the recent passing of A. Sivanandan* himself, whose neglect by today’s generation is both disappointing and shameful. He was, for four decades, the Director of the Institute of Race Relations (IRR), and the founding editor of its journal Race & Class, which has had contributions from the likes of Noam Chomsky, Edward Said, Walter Rodney, Aijaz Ahmad, Chris Searle, Manning Marable, Cedric Robinson, Ilan Pappe, Basil Davidson, John Berger, Eqbal Ahmad, Angela Davis and John Newsinger.

Sivanandan was in a class of his own as a thinker, writer and speaker. His deliberations on the issues of racism, immigration, capitalism and imperialism were a particular beacon of hope for activists and communities during the bleak Thatcher years of the 1980s. He was a visionary whose insights were original and whose ideas still remain relevant today, yet his name – with few honourable exceptions – is seldom, if ever, cited by the British left. Simply put, Sivanandan’s influence upon those involved in the anti-racist movement – whether they are aware of it or not – is monumental.

Sivanandan was very conscious of how racism evolved – especially with changes in the economy and how reduced demand for labour consequently affected immigration policy. His landmark 1976 essay Race, Class and the State was the first serious and radical explanation of the political economy of race and immigration in post-World War Two Britain, and set the benchmark for all future analysis.

Over the years he documented and explained the ‘rationale’ for the racism that was weaponised by the state and the popular press against black peoples (using the term in the political sense; i.e. those deemed outside of ‘whiteness’), including refugees, asylum seekers and migrant workers. There was, according to Sivanandan, “The racism that discriminates and the racism that kills.” He mostly concerned himself with the latter, focusing on its primary victims: the working class and those catching hell on the streets, rather than the middle-class woes of well-to-do ethnic minorities.

Often mischaracterised by the liberal-left, bourgeois academics and middle-class minorities alike as an out-dated relic from the past, it was clear to anyone who read and reflected upon Sivanandan’s writings or listened to him speak that, in fact, it was they who were being left behind by reality – a failure to ‘catch history on the wing’, as he put it. Take, for example, the continued inability of some elements of the left to incorporate race into their analysis of class. The latest and most notable illustration of this is the ‘Lexit’ brigade, who (mis) calculated that they could hijack the ‘Brexit’ narrative from the long-term clutches of the right – a mouse riding the back of a tiger, as one commentator astutely put it.

In his final public statement, writing the foreword for a report by the IRR on the spike in post-referendum racial violence, Sivanandan referred to the entire Brexit façade as being “born of fortuitous circumstances” and “lacking programme or policy” – the only discernible plan subsequently agreed upon by the government being the tactical weapon of racism and a reactionary ideology of nativism. He also blamed the government for reducing racial violence to the status of ‘hate crime’, achieving the dual outcome of reducing the former into an individualised issue of law and order, and thus, secondly, absolving itself of its own responsibility in implementing racist policies and creating a toxic environment. Asked about his political thought and the work of the IRR in a 2013 interview, Sivanandan’s words, though reflections, appear as a forewarning in light of Brexit and its cheerleaders amongst the left:

“We contested the Marxist orthodoxy that the race struggle should be subsumed to the class struggle because once the class struggle was won, racism would disappear. That did not speak to the lived experience of the black working class. Racism had its own dynamic. ‘Black and White unite’ is a goal to strive for, not the reality on the ground and therefore required that White and Black workers had to traverse their own autonomous routes to the common rendezvous… We have fought the idea that racism was an aspect of fascism – our take was that racism was fascism’s breeding ground.”

There were few, if any, contemporary intellectuals who wrote with such lucidity and poetry on the intersection of race and class. Sivanandan was as at ease quoting T.S. Eliot, Keats and Oscar Wilde as he was citing Marx, Fanon and Cabral. However, unlike some theorists that name-drop for their egos and obfuscate pretentiously at their audiences, every sentence of Sivanandan’s was both intelligible and purposeful. He would often reaffirm, “The people we are writing for are the people we are fighting for.”

There were few, if any, contemporary intellectuals who wrote with such lucidity and poetry on the intersection of race and class. Sivanandan was as at ease quoting T.S. Eliot, Keats and Oscar Wilde as he was citing Marx, Fanon and Cabral. However, unlike some theorists that name-drop for their egos and obfuscate pretentiously at their audiences, every sentence of Sivanandan’s was both intelligible and purposeful. He would often reaffirm, “The people we are writing for are the people we are fighting for.”

He produced neither full-length works nor any academic treatises. Instead, Sivanandan wrote complex-yet-digestible essays of a prophetic nature for those at the barricades of the struggle, enabling those at the grassroots to see the wood from the trees. Some of these writings were subsequently compiled into separate anthologies on three occasions: A Different Hunger (Pluto Press, 1982); Communities of Resistance (Verso, 1990); and the most recent collection, Catching History on the Wing (Pluto Press, 2008).

Experiencing racism in Ceylon

Sivanandan was born on 20 December 1923 in Colombo, then capital of the British colony of Ceylon (later ‘Sri Lanka’). He was from an ethnic Tamil background, his family originally from Jaffna – the cultural capital of the Tamil people, who are predominantly found in the North-East of the island. Though there were already tensions lingering under the surface, when the country gained independence in 1948 it rapidly began to disintegrate along ethnic lines. This was no accident: as Sivanandan later summarised British colonial rule with his trademark simplicity, “It divided in order to rule what it integrated in order to exploit.”

Politicians from the majority Sinhalese ethnic group – helped by the growing clout of the fascist-minded Buddhist clergy – used racism as a tactic in order to achieve a ready-made political majority at the expense of the numerically fewer Tamils. Their first crime upon independence was to render stateless, and then disenfranchise, the Tamils of the central hill-country, who were amongst the most militant workers on the island. These people were descendants of indentured labourers brought over from South India by the British in the mid-nineteenth century to toil on their lucrative tea plantations, which Sivanandan later described as a “colony within a colony.” The ruling elites next focused their efforts on the ‘indigenous’ Tamils.

Sivanandan witnessed the total bankruptcy and betrayal of the Sinhalese left as they subsequently chose an exclusionary racial ‘solidarity’ over a united class struggle, eventually collaborating with the government. Though the means used were initially discriminatory legislation – orchestrated by the state through the avenues of language, education and employment – they soon evolved into targeted racial violence against Tamils, led by Sinhalese ‘Buddhist’ monks and goon squads.

After surviving the 1958 anti-Tamil pogroms in Colombo, Sivanandan fled to London, where he walked straight into another episode of racial violence – this time the attacks on the black community in Notting Hill. Directly experiencing these two horrific incidents of violence convinced Sivanandan that he could not stand on the sidelines any longer, that he needed to study the root causes of racism in order to fight against it.

The Empire Strikes Back

When Sivanandan obtained work as a librarian at the Institute of Race Relations in 1964, it was a government orientated think tank used by British foreign policy planners in order to serve the corporate interests of its multi-national funders. After the so-called ‘race riots’ of 1958, the IRR began to focus more attention on domestic ‘race relations’ – as opposed to combating racism itself.

Sivanandan and other more radical members of staff began to question the ethical responsibility of the IRR, clashing with management over their right to scrutinise government policy on race and question the racist frameworks of the institute’s policy-orientated research. With the rise of fascist politics in Britain, along with racist anti-immigration legislation controls (starting with the 1962 Commonwealth Immigrants Act), which the Labour Party also capitulated to, the seeds of revolt were planted. As Sivanandan was to later summarise, “What Enoch Powell says today, the Conservative Party says tomorrow, and the Labour Party legislates on the day after.”

By 1972, the contradictions within the institute had reached a point of no return. That year, Sivanandan led a dramatic and gruelling struggle by the staff and took control of the IRR from its council, supported by a democratic mandate from its membership. The organisation immediately lost its wealthy funders and was thus transformed. Its journal, Race, was renamed Race & Class, its aim now dedicated to ”Black and Third World liberation.” Sivanandan described the IRR’s new function as “a think-in-order-to-do-tank for Black and Third World peoples” and a “servicing station for oppressed peoples on their way to liberation.”

Black British history and education

In her obituary of Sivanandan, Liz Fekete, current Director of the IRR, made a point of mentioning his recent concern that younger generations of British anti-racist activists were ignorant of their own history, tending to focus solely on American movements such as the Black Panther Party for inspiration and guidance. However, Sivanandan articulated previously unknown stories of how black peoples had resisted on this side of the Atlantic, even when solidarity from their white comrades was rather lacking.

In her obituary of Sivanandan, Liz Fekete, current Director of the IRR, made a point of mentioning his recent concern that younger generations of British anti-racist activists were ignorant of their own history, tending to focus solely on American movements such as the Black Panther Party for inspiration and guidance. However, Sivanandan articulated previously unknown stories of how black peoples had resisted on this side of the Atlantic, even when solidarity from their white comrades was rather lacking.

His 1981 essay From Resistance to Rebellion: Asian and Afro-Caribbean Struggles in Britain is one of the best examples of this alternative, history-from-below. It is an electrifying piece of writing – its opening lines encapsulating Sivanandan’s gift of joining the dots from the colonies to the mother country. The introduction begins in 1940, with Udham Singh’s hanging in London after his revenge shooting of ‘Sir’ Michael O’Dwyer – the man responsible for the 1919 Amritsar Massacre – but ends with the former’s lesser-known involvement in setting up the Indian Workers’ Association during his stay in England.

The essay made a massive impact upon its first publication and, decades on, there are still numerous stories told by activists recounting how they would copy and distribute multiple copies of it everywhere.

By incorporating and transmitting the unwritten racial dimension within the historical class struggle – something the orthodox white British left, including such luminaries as E.P. Thompson and Eric Hobsbawm (and today’s pale imitations Ken Loach, Owen Jones et al) have generally failed to do – Sivanandan inspired others to do likewise. His legacy can be seen, for instance, in the works of Satnam Virdee, Anandi Ramamurthy and Arun Kundnani; as well as the recent commemorations of the epic Grunwick Strike of 1976-78 – a struggle that was led by Asian women and had lasted longer than the Miners’ Strike of 1984-85.

Sivanandan also had a pedagogical impact through an influential series of educational booklets published by the IRR in the 1980s that attempted to address the absence of black history in schools, particularly racism and its connection to imperialism. There were four booklets in total: Roots of Racism; Patterns of Racism; How Racism Came to Britain; and The Fight Against Racism – the latter two focused on the British context, whereas the earlier books were more general in emphasis. How Racism Came to Britain was especially explosive in its impact, resulting in a sustained witch-hunt led by the right against the IRR, and even attempts by the Secretary of State for Education to ban the books from schools.

This initiative can be seen as a precursor to some of the more recent campaigns of our times, many currently being fought at several universities throughout the country, such as ‘Rhodes Must Fall’ and, in particular, ‘Why is My Curriculum White?’ and ‘Decolonising Our Minds’. Sivanandan would certainly support such initiatives, though he would surely warn the more liberal-minded of these students against merely settling for redistribution of quotas or greater diversity (e.g. more non-white thinkers included in philosophy courses/modules). In one of the forewords he wrote for the IRR series, Sivanandan critiqued multi-cultural education for its limitations, namely for only emphasising differences between cultures; he stressed (below) that a critical re-evaluation – and thus, transformation – of entire institutions and orthodoxies was required to truly ensure a radical change in such a racist society:

“Our concern is not centrally with multi-cultural multi-ethnic education but with anti-racist education (which by its very nature would include the study of other cultures). Just to learn about other people’s cultures, though, is not to learn about the racism of one’s own. To learn about the racism of one’s own culture, on the other hand, is to approach other cultures objectively.”

“Sivanandan’s influence upon those involved in the anti-racist movement – whether they are aware of it or not – is monumental.”

“We are here because you were there”

Whereas some on the left retained their endless faith in trade union agitation in social democracies, harking back to some Keynesian ‘golden era’, Sivanandan refused to go along with religious orthodoxies and rigid dogmatism. He forewarned of the massive changes taking place as developed countries within the capitalist metropolis evolved from industrial to information-based economies. These themes were brilliantly analysed and anticipated in essays such as Imperialism and Disorganic Development in the Silicon Age, written in 1979, and in New Circuits of Imperialism (1989). Sivanandan pointed out that labour in the west was so preoccupied with emancipating itself from capital, that it had not been able to prepare for the opposite scenario: with the development of technology, capital had been able to emancipate itself from labour, leaving the working class in the metropolitan countries paralysed, with no economic – and therefore political – clout.

However, Sivanandan reserved sharp criticism for those who declared the class struggle – even within the imperial centre – as redundant or futile, consistently citing the crucial role of part-time, temporary or migrant labour, such as security guards, fast-food chain workers, porters, cleaners, etc. He described their precarious existence as, “rightless, rootless, peripatetic and temporary,” and without whose labour “post-industrial society cannot run”. However, as recently demonstrated by the long and arduous struggle of the cleaners at SOAS – predominantly women workers from ‘Latin’ America – even the toughest battles can be won by the most marginalised and exploited.

With his holistic view of the world, Sivanandan stood in sharp contrast to the dogmatic Eurocentric Marxists who have dominated the discourse of the left (or what’s left of the left). Unlike them, he positioned his analysis of capitalism (i.e. ‘the system’) around imperialism (i.e. “the project”) and its devastating effects – via globalisation (i.e. “the process”) – upon the peoples at the periphery of the world economic system. Sivanandan would always demonstrate cause and effect, describing the economic policies (e.g. Structural Adjustment Programmes) of transnational organisations (e.g. the EU, the IMF, the World Bank, etc) and multi-national corporations, as well as their political and military agents, whether in the form of nation-states or through collective alliances such as NATO. He would explain how the actions of these entities caused the forced migration of people from the Third World – often as a direct consequence of war and poverty – on a mass scale into the metropolitan countries of the West, where upon arrival they would often meet new racisms and oppressions.

Journalist Phil Miller is the author of two groundbreaking reports that investigate Sri Lanka’s intimate post-independence relationship with its former colonial power. His research has exposed how Britain provided high-level counterinsurgency assistance to the Sri Lankan state in its genocidal war against Tamils. Miller also demonstrates in his writings how the Home Office uses repressive policies against those same people when they seek refuge here in the UK. When asked to describe the political impact of Sivanandan upon his work, Miller stated, “Sivanandan’s aphorism ‘We are here because you were there’ informed my approach to writing about Tamil asylum cases. It also prompted me to research British foreign and colonial policy towards Sri Lanka/Ceylon to gain a deeper understanding of how Britain was partly responsible for the displacement of Tamils from their homeland.”

Identity politics and ‘New Times’

Though critical of economic determinism, Sivanandan cautioned against the potential excesses of the politics of identity. In RAT and the Degradation of Black Struggle, written in 1985, he delivered a scathing indictment of the US-imported ‘racism awareness training’, which removed state and institutional responsibility for racism, instead turning it into a ‘natural’ social phenomenon independent of material conditions, a ‘white disease’. This type of approach is perhaps best exemplified by the ‘calling-out’ culture of social media, and the rise of the politically limited and intellectually lazy discourse centred on personal ‘privilege’. Today’s Twitter generation often prioritise the issue of whoretains cultural rights instead of fighting for the right for an inclusive political culture, i.e. within the context of class. For Sivanandan, the concept of ‘the personal is political’ only concerns what is owed to one by society, whereas its inversion – ‘the political is personal’ – concerns what is owed to society by one.

He was sceptical of identity politics as a means to liberation, referring to it as an “inward-looking, naval-gazing exercise” that stemmed from the individual. But the self is also found within the world, pointed out Sivanandan. By focusing instead on grassroots struggles, such as migrant worker rights, addressing deaths in custody or stopping deportations of asylum-seekers – which are inherently community-orientated and organic – one begins to change the field of play, rather than merely changing the goal-posts. Throughout his work and life, he repeatedly stressed, “Who you are is what you do.”

Sivanandan’s prescient analysis (below) in 1990 (before ‘intersectionality’ became the favourite buzzword of humanities and social sciences departments and the blogosphere) still reverberates today with regard to the potential pitfalls of a politics of identity bereft of class, which leads to a harmonious liberal accommodation with capitalism. A women’s movement that does not factor in the poorest and most marginalised women; or a Green movement that does not consider the ecological devastation caused by Western capitalism in the Third World; or a Peace movement that cares only for preventing nuclear catastrophe at home but not stopping the arms industry from fuelling wars and genocide abroad, wrote Sivanandan, becomes narrow in focus, elitist and reformist at best – and ultimately permits capitalism to continue thriving via imperialism. Class is not simply another ‘identity’ but is, rather, an objective reality and the modality through which identities must be perceived. Oppression goes in tandem with exploitation, and vice versa. As Sivanandan put it:

Sivanandan’s prescient analysis (below) in 1990 (before ‘intersectionality’ became the favourite buzzword of humanities and social sciences departments and the blogosphere) still reverberates today with regard to the potential pitfalls of a politics of identity bereft of class, which leads to a harmonious liberal accommodation with capitalism. A women’s movement that does not factor in the poorest and most marginalised women; or a Green movement that does not consider the ecological devastation caused by Western capitalism in the Third World; or a Peace movement that cares only for preventing nuclear catastrophe at home but not stopping the arms industry from fuelling wars and genocide abroad, wrote Sivanandan, becomes narrow in focus, elitist and reformist at best – and ultimately permits capitalism to continue thriving via imperialism. Class is not simply another ‘identity’ but is, rather, an objective reality and the modality through which identities must be perceived. Oppression goes in tandem with exploitation, and vice versa. As Sivanandan put it:

“If these issues are fought in terms of the specific, particularistic oppressions of women qua women, blacks qua blacks and so on, without being opened out to and informed by other oppressions, they lose their claim to that universality which was their particular contribution to socialism in the first place. And they, further, fall into the error of a new sectarianism – as between blacks versus women, Asians versus Afro-Caribbeans, gays versus blacks and so on – which pulls rank, this time, not on the basis of belief but of suffering: not who is the true believer but who is the most oppressed. Which then sets out the basis on which demands are made for more equal opportunities for greater and more compound oppressions in terms of quotas and proportions and that type of numbers game. That is not to say that there should be no attempt to redress the balance of racial, sexual and gender discrimination, but that these solutions deal not with the politics of discrimination but its arithmetic – giving more weightage to women here and blacks there and so rearranging the distribution of inequality as not to alter the structures of inequality themselves. In the process, these new social movements tend to replace one sort of sectarianism with another and one sort of sectional interest for another when their native thrust and genius was against sectarianism and for a plurality of interests.”

The essay The Hokum of New Times, where most of the aforementioned criticisms of identity politics is found, has become more notorious for other reasons. Sivanandan, out of comradely love and intellectual honesty, ruthlessly eviscerated the arguments of, amongst others, his friend Stuart Hall in a scintillating polemic. Hall had outlined in the pages of influential magazine Marxism Today how the industrial age was giving way to ‘New Times’ – a rapidly accelerating information age, whereby, in the process, “Our own identities, our sense of self, our own subjectivities are being transformed.”

The Marxism Today collective were terrified of allowing Thatcher, and the right, to consolidate their own ideas within the increasingly alienated and disillusioned general public. The solution, according to the disciples of ‘New Times’, was that one should begin to resist through the vehicle of identity and culture – as opposed to linking them to, let alone changing, the economic base. Hall, in particular, consequently focused much of his intellectual work on the superstructure politics of culture and ideology, rather than the politics of economy: a total inversion of Marxist methodology. “Philosophers have interpreted the world,” Marx famously said, but instead of seeking to change it, added Sivanandan, referring to the intellectuals of Marxism Today, now they sought to “change the interpretation.”

Stuart Hall was also rebuked for overlooking in his analysis the masses of workers throughout the Third World, upon whose exploitation these Eurocentric ‘New Times’ would be owed to and built upon. In fact, Hall had, in 1986, used the previous year’s hugely popular ‘Live Aid’ concert of Bob Geldof – Bono’s predecessor as musician-turned-missionary – as ‘proof’ of the changing political climate in Thatcher’s Britain. Sivanandan had no time for such liberal window-dressing, castigating Hall for changing the discourse of anti-imperialism into one of Western humanism and charity.

Sivanandan ‘s The Hokum of New Times essay can also be interpreted as a prologue to the left’s capitulation under Thatcher; its submission to her mantra of ‘There is no alternative’ (TINA). He infamously characterised the political conclusions of ‘New Times’ as ‘Thatcherism in drag’ – an especially sharp denunciation since it was Hall himself who had initially coined the term ‘Thatcherism’, arguing many years ago that she was not ‘just another’ Tory. With his relentless critique, Sivanandan in some ways projected how the Marxism Today collective’s attempts to fight Thatcherism perhaps unwittingly led them to midwife the birth of New Labour and the ‘Third Way’ ideology of its intellectual guru, Anthony Giddens.

Marxism Today’s editor Martin Jacques went on to found New Labour-supporting think-tank Demos with Geoff Mulgan, a regular writer for MT who later became a key policy adviser for yet another former contributor: none other than Tony Blair. Indeed, when asked years later, Thatcher is said to have cited her greatest achievement as New Labour. Stuart Hall, who had briefly befriended Blair in the 1990s, eventually conceded what Sivanandan had had the foresight to warn against, complaining to the Observer in 1997, “All he [Blair] seems to be offering is Thatcherism with a human face.”

Sivanandan was also far-sighted enough to warn communities of being the unwitting victims of the age-old British tactic of divide-and-rule. In the Scarman report of 1981, which was in response to the Brixton riots of the same year, the response of the state was to co-opt and buy-off black struggle – as opposed to suppressing it as it had always done before. Rather than admitting to state and institutional racism, the Scarman report had concluded that different ethnic groups had different needs (or ‘racial disadvantages’) that must be accommodated (i.e. compromised) by the state – whether by grants or through positive discrimination. Sivanandan later described the latter as akin to “breaking our legs and giving us crutches.”

The logical conclusion of this new government policy was the rise of a multitude of ethnicities, self-appointed leaders and cherry-picked representatives coming to the fore, disaggregating the previously militant black working class. Sivanandan had warned about the flight of race from class in 1983, telling communities, “We don’t need a cultural identity for its own sake, but to make use of the positive aspects of our culture to forge correct alliances and fight the correct battles.” It is important to note, however, that his earlier criticisms of multi-culturalism were specifically about the post-1981 state policy of divide-and-rule; he later defended organic, community-led multi-culturalism – so long as it was infused with anti-racism. This was in light of attacks upon this brief era of relative progress from nativists and advocates of ‘British values’ after the 2001 race riots in northern England, and the 9/11 and 7/7 terrorist attacks.

When memory dies, a people die

In terms of his birthplace, Sivanandan’s lasting legacy is his epic historical novel When Memory Dies – probably the most ambitious and significant piece of literature written about Sri Lanka in the last century. It is his first and only novel, published in 1997 when he was in his early 70s, and, tellingly, took him around two decades to write. The novel tells, in three different parts, the history of the island: from colonial British rule, to the newly independent Ceylon and, finally, to the ethnocracy that rebranded itself in 1972 as ‘Sri Lanka’.

In terms of his birthplace, Sivanandan’s lasting legacy is his epic historical novel When Memory Dies – probably the most ambitious and significant piece of literature written about Sri Lanka in the last century. It is his first and only novel, published in 1997 when he was in his early 70s, and, tellingly, took him around two decades to write. The novel tells, in three different parts, the history of the island: from colonial British rule, to the newly independent Ceylon and, finally, to the ethnocracy that rebranded itself in 1972 as ‘Sri Lanka’.

When Memory Dies is a story told not from the point of view of authoritarian presidents and prime ministers, nor that of jingoistic army commanders or bigoted religious leaders, but from the viewpoint of the subaltern – the ordinary people. It threads together various features of colonial rule in Ceylon, addressing issues such as the wretched conditions of the workers that plucked the tea for the imperialists; the hegemony of the English language over the natives; and debates between characters arguing reform versus revolution when deliberating over what form the class and anti-colonial struggles should take.

Readers familiar with Sivanandan’s better-known essays on racism will stumble across many of his political aphorisms and poetic language throughout the novel. “If you read my political stuff you’ll find it is creative – I hope my creative writing is political – I don’t separate the two,” he once declared. To understand Sivanandan the man; what events formed his personal character and political principles, and the struggles of the people of the island, especially his fellow Tamils – massacred in their tens of thousands by the Sri Lankan state in 2009 – this novel is fundamental reading. Indeed, he once told this writer, “My book is my gift to my country and my people.”

In 2016 students at SOAS were asked to submit a list of key figures important to decolonisation for artists to commemorate in a series of murals. The-then president of the Tamil Society at the university, Bava Dharani, proposed that Sivanandan’s image should be included. When asked to elaborate upon her reasons for choosing him, she explained

“I think Sivanandan’s work on race was not only critical but also provided a different perspective on decolonisation, race, etc. Given his background, being a Tamil forced to flee from Sri Lanka and finding himself in the UK, his writing had a lot of heart – especially When Memory Dies. I remember being moved by and relating to so many parts of that book. And this quote – it stayed with me because it highlighted how important it is to write our own history. That is exactly what I think SOAS is trying to achieve with all these movements towards decolonising the syllabus. It just made sense for him to be up there.”

Alas, thus it came to pass: those frequently in the area may have noticed a painting of Sivanandan’s face – accompanied by the quote in question (picture in the photo at the top of the essay) from his novel – in the students’ union bar at SOAS. It is fitting that Sivanandan, whose funeral took place exactly forty-two years to the day that his hero Paul Robeson died, is honoured at SOAS – the institution where Robeson himself once studied and was later immortalised with a building named in his honour.

Now, more than ever, it is time for those who tremble with indignation at injustice to acquaint ourselves with the writings of A. Sivanandan to help guide us for the battles ahead – to be proactive rather than reactive in the struggle for economic, political and social justice, both home and abroad. We must catch history on the wing.