‘Tamil Guardian’ editorial, London, February 12, 2017

Election results by ethnicity Feb 2018 PDF

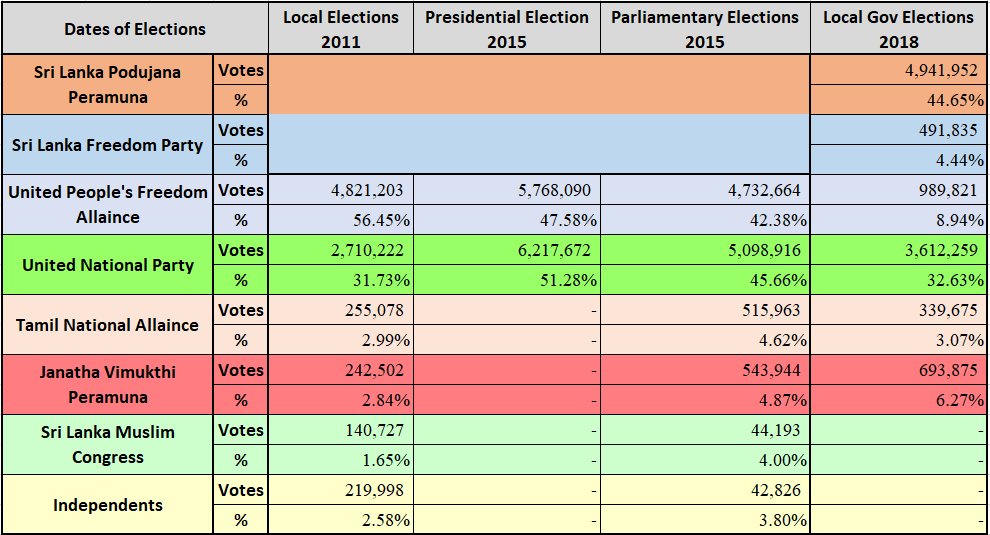

Sri Lanka’s unity government suffered an electoral blow at local government polls this weekend, just three years after its surprise victory. The Sinhala people renewed their support for the former war-time president, Mahinda Rajapaksa, who asked voters to use the polls as a de-facto referendum on the unity government’s constitutional reform process, which he warned was the gateway to federalism. The Tamil people reaffirmed their support for the Tamil struggle, with Tamil nationalist parties winning the vast majority of seats in the North. Notably however, the Tamil National People’s Front (TNPF) made unprecedented gains in key wards, at the expense of the Tamil National Alliance (TNA). The TNA, which had provided unconditional backing to the Ranil-Sirisena coalition despite the government’s repeated failure to deliver on key pledges to the Tamils, was numerically successful but short of a majority in all councils across the North.

The government’s failed promise of exemplary governance, albeit a factor, was not the deciding one. Many of its reforms were after all deeply tangible in the South, with the opening up of political space and freedoms. For the ‘moderate Sinhala voter’, said to have been instrumental in securing the 2015 Ranil-Sirisena win, the pace of reform whilst falling short of the promised 100 days, was nonetheless greater than was achieved in 10 years of Rajapaksa. The results are instead a paragon of the island’s unreconciled fault line of the Tamil question. The South voted for Rajapaksa fearing a slippery slope towards the concession of power to the Tamils and federalism, while Tamils rebuked the TNA for veering too far from core Tamil political aspirations outlined in the Thimphu Principles and for propping up a draft constitution that fell far short from delivering on the party’s election promise of a federal state.

Ranil-Sirisena’s 2015 electoral victory, contrary to how it was portrayed at the time, was never a Sinhala endorsement of power sharing or justice for Tamils – a truth that was not lost on the president and prime minister, who routinely reaffirmed their rejection of federalism and any meaningful accountability mechanism. Sinhala voters had instead punished the Rajapaksas for their burgeoning nepotism and corruption, and for allowing their murderous rule to extend beyond the Tamil areas into Sinhala ones. As this election illustrates however, the Sinhala electorate’s censure of illiberal governance will never be at the expense of safeguarding a Sinhala majoritarian Sri Lanka. Through Sri Lanka’s 70 years of independence Sinhala ethno-nationalist parties have been voted into power whenever any possibility of power sharing with Tamils drew near, and governments who oppressed Tamils have been consistently rewarded by Sinhala voters. Rajapaksa was not defeated because he presided over the mass slaughter of tens of thousands of Tamils; he was rewarded with another election victory.

If there was ever a window of opportunity for internal change towards a political solution or meaningful accountability, that has now firmly closed. Difficult reforms and conversations that were not pursued when the unity government was in the strongest possible position are not going to be pushed through now in light of Rajapaksa’s re-emergence – Ranil and Sirisena know full well to do so would seal their demise. As the Tamils have long argued, heightened international pressure is the only way to effect change, and firm international scrutiny is the Tamil people’s only present safeguard against repression by the state. Rajapaksa’s return to the political stage as well as a Sri Lankan military brazen with impunity and further emboldened by the presence of an increasingly limp government fills Tamil minds with terror. Nothing exemplifies this further than Sri Lanka’s Defence Attache making a throat slitting threat to Tamils in London last week.

Rising Tamil frustration and anger at the TNA leadership’s appeasement of the government, despite the latter’s repeated refusal to address key Tamil concerns, led to the first electoral endorsement of the TNPF. The TNPF’s hard earned gains stand as a testament to the party’s steadfast commitment to the Tamil struggle. It is now incumbent on the TNPF to build on this momentum, establishing an inclusive, broad based force of political leadership. The TNA must meanwhile reflect carefully on its electoral set back. Its leadership, which habitually uses electoral successes to silence dissenting voices, has long taken the Tamil people for granted. The TNA must now change. It must put an end to its opaque diplomacy on the Tamil national question, in favour of a transparent approach. The TNA, which at election time has always relied heavily on invoking their historic links to the LTTE and claiming to be their legitimate heirs, must now uphold its election promises and the mandate granted to it by the Tamil people. To this end it is positive to note a humbled TNA after the election, calling on all Tamil nationalist parties to unite towards federalism. Coalition building between the two main Tamil parties may prove difficult after a bitterly-fought campaign and core differences on principles. However there must be unity in purpose amongst all shades of Tamil nationalist parties. The paramilitary EPDP can never be a partner. The Sinhala Buddhist state-building project remains a grave threat to the Tamil nation – the safeguarding of the Tamil people through the establishment of a truly federal system of governance, in addition to credible, international accountability mechanisms must remain at the forefront of Tamil politics. Now it is up to the Tamil leaders to deliver.