Pressure mounts to account for past actions in nation where even truth and reconciliation commission is lacking

by Kingsley Karunaratne, ‘UCA News,’ May 10, 2018

A mother of three children who disappeared during Sri Lanka’s long-running civil war holds their photographs at a makeshift roadside hut in the town of Vavuniya as she continuous her protest urging the government to investigate what happened to them in this Feb. 20, 2017 file photo. (Photo by Quintus Colombage/ucanews.com).

The situation is likely to become even more precarious if a transitional justice mechanism for wartime atrocities covering the civil war from 1983 to 2009 is not set up, despite requests from the international community.

The urgent need for a war crimes tribunal — or something of that nature — was addressed during the 37th Session of the United Nations Human Rights Council (UNHRC), which concluded in Geneva on March 23.

According to a resolution adopted at the meeting, Sri Lanka has been granted two more years to show its commitment to holding those guilty of wrongdoing to account while also working toward national reconciliation.

Filippo Grandi, the High Commissioner of the UNHRC, has called on the UN Human Rights Council to explore more avenues to foster accountability for past crimes.

He also expressed concern over the lack of progress being made in such projects.

The prime concern of the international community is that justice be meted out. However the three agencies that Sri Lanka told the UNHRC in 2015 it would set up have failed to materialize.

This has left many wondering if the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC), Reparation Office and Judicial Accountability Mechanism (a special court to try war crimes) will ever see the light of day.

Accounts of the bitter civil war between the Sinhalese and Tamil Tigers fighting for an independent state suggest that up to 40,0000 Tamil citizens lost their lives during the 37-year conflict.

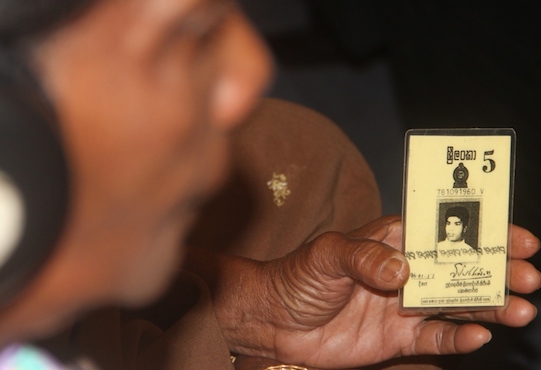

The parent of one of the men who disappeared during the war holds his national identity at the Office of Missing Persons in Colombo on March 3. (Photo by Niranjani Roland/ucanews.com)

But until now only the Office of the Missing Persons (OMP) has been established to explore the truth about what happened to hundreds of people who vanished under mysterious circumstances.

The city said it has allocated 1.4 billion rupees ($9 million) to get to the bottom of these suspected enforced disappearances.

The problem is that even when momentum has built, for example with the establishment of the OMP, a turn of events usually unfolds to render the development ineffective.

In this case, the bill was passed by parliament last year and the president promulgated it in July. That paved the way for the Constitutional Council to recommend a chairman and other members.

After a surprising delay of seven months, the president appointed a chairman and members of the authority on Feb. 28. It has recently begun to recruit the required personnel for its operations.

Setting up the OMP is a step in the right direction and one that is absolutely essential for the looming accountability process.

But that is not all that is needed. The police must also modernize and adapt to the times by showing zero tolerance when it comes to the torturing of suspects, a practice the victims of police abuse say is rampant.

Furthermore, Sri Lanka acceded to the Optional Protocol to the Convention against Torture (OPCAT) in Dec. 2017 and passed related legislation

The government promised that all of the key legislation was being put in place, citing how parliament had approved the International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearances on March 7.

However, even if the work is proceeding as claimed, it is moving at a snail’s pace in terms of implementing reform amid constant backpedaling.

Moreover, Colombo recently informed the UNHRC Session that it would implement all of the planned transitional justice mechanisms but only in accordance with the country’s constitution.

Tamil relatives in Vavuniya have been demonstrating since Feb. 20, 2017 to pressure the government to heed their request for information about their missing family members. (Photo by Quintus Colombage/ucanews.com).

In doing this, the government sent a clear message that international participation in the proposed special courts was not only unwelcome — but would not be granted.

Its rationale was that the charter does not allow for the inclusion of international judges, prosecutors and investigators in settling cases.

Foreign Minister Tilak Marapana duly informed the UNHRC that Sri Lanka’s current judiciary and law enforcement mechanisms are fully capable and committed to advancing justice to all concerned.

He said these mechanisms prove their integrity and professionalism over successive decades and that since January 2015 steps have been taken to further strengthen their independence.

In sum, all reconciliation mechanisms will be implemented in accordance with the constitution, he added.

He also blamed the negative coverage on the media and opposition’s decision to focus on the nation’s hybrid court structure, which he described as part of a campaign to poison public opinion in the south against the state.

In contrast, the government has elected not to comment on the matter when it could easily have taken measures to educate the public about how it stands and why it is adopting this approach.

It is also worth mentioning that the president rejected an appeal from the United Nations in 2017 to have international judges participate in investigating probes into wartime atrocities.

Meanwhile, some analysts have questioned the impartiality of foreign judges. And certainly the Sinhala population and armed forces may think that may.

The best way forward is for Sri Lanka to create a judicial process of its own that impartial and guided by both the Constitutional Council and parliament.

Another question is whether the reform agenda will be continued.

Sri Lanka’s ruling coalition government has promised to implement three key policies — abolishing the executive presidency (which is considered anti-democratic); reforming the electoral process; and solving the National Question of federalism vs. autonomy — but how are these to be resolved?

The 19th Amendment (19A) to the charter was passed by the nation’s 225-member parliament on April 28, 2015 by an overwhelming majority with 215 voting in favor.

This effectively reduced the executive powers of the president and transferred the difference to parliament while also reconfiguring the nation of that body by doubling the number of local government members and mandating female representation of at least 25 percent.

However fulfilling the pledges mapped out that year require the introduction and approval of a new charter. Not everyone was happy about this, especially Buddhist monks who responded with mass protests.

It was even opposed by Cardinal Malcolm Ranjith, the archbishop of Colombo, while former president Mahinda Rajapaksa — now firmly ensconced in the opposition camp — said it threatened to divide the country.

The government answered by saying it was merely a draft that could be amended down the road.

Rajavarothiam Sampanthan, a Tamil politician and lawyer who has led the Tamil National Alliance since 2001 and now ranks as the opposition leader, said recently in parliament that “according to the mandate given to both the president and the prime minister in January 2015 and August 2015, respectively, we must go ahead with the new charter if we want genuine peace in the country.”

In any case now it is the duty of the government to submit its final draft and do what is needed.

In the present context, the stability of the unity government is at stake. But will it be able to get a two-thirds majority to approve the charter?

I’m sure all of the minority parties would pull together to ensure this is the case if the government really is committed to its reformist agenda, and surely we will find out soon.

But the government has failed to address the concerns of the Southern Sinhalese voting base, many of whom were angered by its decision to hound the Sinhalese army for alleged war crimes.

Meanwhile, the establishment and operation of the OMP has also been a cause of concern for many Sinhalese voters down south.

Wherever he goes, Rajapaksa likes to comment publicly on how the government is threatening the very fabric of society by attempting to railroad the new charter while also hunting for so-called “war heroes.”

By war heroes, we refer to those soldiers who sacrificed their lives to save the country but are now subject to prosecution for war crimes including the murder of journalists.

The government is duty-bound to use the media, among other means, to educate the public of its planned reforms legislation designed to promote the development and the nation and people’s wellbeing.

If it fails to do this, the public can easily be misled and therefore oppose said reforms due to the mischievous actions of the opposition who are bent on scoring points ahead of the election.

Regardless, the charter must ultimately be approved by a referendum, which will require the participation of the citizenry.

Finally, the president and prime minister should have close ties and work well together as they two belong to two different parties, which can cause enough friction, while the government is composed of multiple players.

If there is no unity or heartfelt commitment between these two politicians to serve the national interest above all else, there is little hope of them being able to drive forward their reformist agenda.

Kingsley Karunaratne is an administrative secretary at the Rule of Law Forum, which is affiliated to the Asian Human Rights Commission. His organization works toward the radical rethinking and fundamental redesigning of justice institutions in order to protect and promote human rights.