by Sachi Sri Kantha, May 25, 2018

by Sachi Sri Kantha, May 25, 2018

Part 1

Tarzie Vittachi Version

Suppose Tarzie Vittachi’s ‘Emergency ‘58’ book on the anti-Tamil riots in Ceylon has to be written as a play or opera, this will be my listing of the credits:

Chief Protagonists: Sinhalese hoodlums (Goondas aka Veerayas)

Victims: Tamil civilians

Supporting Cast: Maithripala Senanayake (the then Minister of Transport and MP for

Medawachchiya), S.D. Bandaranaike (then MP for Gampaha), K.M.P. Rajaratne (then MP for Welimada), A. Amirthalingam (then MP for Vaddukoddai).

Spoilers: Buddhist monks, UNP leaders – esp. J.R. Jayewardene and Dudley

Senanayake, C. Suntheralingam (then MP for Vavuniya).

Director: S.W.R.D. Bandaranaike (Lokka, lit. The boss)

Script writer: Competent Authority (aka Government censor of the news)

Plot nucleus: Bandaranaike – Chelvanayakam [BC] Pact of July 1957.

Plot thickeners: murder of Mr. D.A. Seneviratne, a former mayor of Nuwara-Eliya,

‘mutilation and murder’ of a Sinhalese woman teacher in Batticaloa,

pirate radio station, Russian hide out.

Deus ex machina: Sir Oliver Goonetilleke (the Governor General)

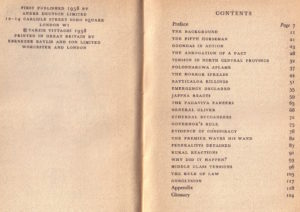

The style adopted for the Emergency ’58 book was akin to that of a lengthy essay. It contained no photos and no index. What I liked best was Vittachi’s profiling of a few characters such as Buddhist monks and few of the chief protagonists for the anti-Tamil 1958 riots. But, he don’t provide any names at all. Here are three snippets:

The style adopted for the Emergency ’58 book was akin to that of a lengthy essay. It contained no photos and no index. What I liked best was Vittachi’s profiling of a few characters such as Buddhist monks and few of the chief protagonists for the anti-Tamil 1958 riots. But, he don’t provide any names at all. Here are three snippets:

On Buddhist monks: On the 1956 election victory of prime minister Bandaranaike that toppled Sir John Kotelawala regime, “The United election front led by Bandaranaike was given massive support by an ad hoc organization of over 12,000 Buddhist monks who came out of their temples and hermitages to canvass openly against the Kotelawala regime which, they claimed, was influenced by the Christians, particularly the Catholics. Here were the best election agents any politician could wish for – 12,000 men whose words were holy to over 5,000,000 people, campaigning for the downfall of the Government, zealously and, what is more, gratis.”

On Sinhalese criminal elements who faked Buddhist monks: “Many thugs – some of them well-known criminals – had shaved their heads and assumed the yellow robes was bhikku. A taxi driver known to the police as a bad hat of a stopped on the road. He had a shaven head. Under the cushions of the seat they found two soiled yellow robes. Police repors record that two ‘monks’ arrested for looting and arson were car-drivers by ‘occupation’. These phoney priests went about whipping up race-hatred, spreading false stories and taking part in the lucrative side of this game – robbery and looting. Whenever the police went after a looter with a shaven head he disappeared into a house and came back in the invulnerable robes of a monk. Monks were ordained in Polonnaruwa in those few days faster than ever before in the history of Upasampada, the Buddhist ordination ceremony. They paid no attention to the sacrilege they were committing in the sacred robes that the Buddha Himself had worn. This menace became so bad that they police took a decision to arrest every man with a shaven head.”

On the heroic action of protagonists: “Bands of Sinhalese roughnecks were suddenly let off the leash in Colombo. Barebodied, sarongs held shoulder high displaying genitals unashamedly, armed with tar-pails and brushes and brooms they shrieked through the streets of Colombo tarring every visible Tamil letter on street signs, kiosk name boards, bus bodies, destination boards, name plates on gates and bills posted on walls. They were armed with ladders to reach roof level where necessary.

Outside Saraswathie Lodge – a ‘Brahmin’ thosey kiosk in Bambalapitiya – I watched a gang of these goondas smearing tar on the Tamil language poster advertising the Thinakaran newspaper for sale. Someone shouted to the tar-brush artist: ‘Go on. Paint a huge Sinhala Sri sign on the bastard’s door. The artist beamed at this inspiration but his past caught up with him at this very moment. He handed over the brush tamely to another: he himself was completely illiterate. He could not write even the Sri in Sinhalese. These were the types who were so vociferous about the glory of the language for which they were willing to exterminate a people and vivisect a nation.”

Tarzie Vittachi

It should be noted that the much hackneyed word terror which was first promoted into the Sri Lankan political lexicon in 1971 (during the first JVP insurgency) and came to be solely identified with LTTE in 1983, was first introduced by Vittachi in this Emergency ’58 book. He deserves priority. This is what he wrote in the Preface to the book.

“Emergency ’58 is not likely to please every reader. On the contrary, it is certain to displease many. I do not know how to write with text-book discretion about the suffering we saw around us and the terror and the hate on the faces of people we had known all our lives. Human history can never be a chronological festoon of events held together by nicely defined causes. The story of a man is the story of a succession of states like love, fear, hate, indecision, self-assurance, ecstasy, depression.”

On the birth of Emergency ’58 book, Mathew Barry Sullivan noted in 1997 that Vittachi “left his job and in five weeks wrote a strictly factual but vehement book about the forces and policies which were finally destroying the age-old toleration and harmony of his homeland. He took the typescript to London himself and found a publisher, Andre Deutsch who brought the book out within three weeks. Emergency ’58 was at once banned in Ceylon, and became an immediate best seller in Asia.”

Maybe, due to such haste, I noted that some factual and interpretational errors had crept into the book. Here are two. In page 20, Vittachi mentions that after the 1956 Sinhala-Only Act, “Religious rivalry grew apace.” In fact, there was NO religious rivalry between Buddhism or Hinduism, Buddhism or Christianity, Buddhism or Islam. The political situation changed to Buddhist hegemony over other three practiced religions of the island. In page 24, Vittachi had recorded (related to the anti-Sri campaign promoted by the Tamil Federalists in early 1958), “The Government took a top-level tactical decision not to prosecute any of the offenders for fear that they would be built up into martyrs. Federal supporters went about in the Peninsular and the east coast with illegal number plates.” This was erroneous. In fact, many were held in detention and jail for spearheading the anti-Sri campaign in Jaffna.

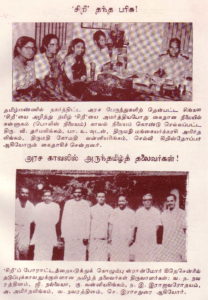

Federal Party Anti-‘Sri’ campaigners held in detention, 1958

The Federal Party’s Silver Jubilee souvenir (1974) carries two photos (which I’ve scanned and provide nearby) in one page of those who were detained during the anti-Sri campaign in 1958. The top photo with the caption The Gift of Sri’ shows four individuals (3 women and one man) with the Police Chief of Chunnakam police station. The caption notes, Mr. V. Dharmalingam [He was not an MP then, though it indicates as such.] with three women from left to right Ms. Christopher, Mrs. Komathi Vanniasingham (wife of K. Vanniasingham, MP) and Mrs. Mangayarkarasi Amirthalingam (wife of A. Amirthalingam, MP). The lower photo with the caption, ‘Tamil Leaders under government detention’ shows 7 individuals who were detained at Colombo Stanmore Crescent. They were from left to right, V.N. Navaratnam (MP for Chavakachcheri), G. Nalliah, K. Vanniasingham (MP for Kopay), N.R. Rajavarothayam (MP for Trincomalee), A. Amirthalingam (MP for Vaddukoddai), V. Navaratnam and C. Rajadurai (MP for Batticaloa).

Amirthalingam’s biographer, T. Sabaratnam, writes as follows: “Sinhala ‘Sri’ buses were again sent to Jaffna on 19 April, the day after the abrogation of the [B-C] Pact. [Note by Sachi: Sabaratnam has been careless with dates. The B-C Pact was abrogated on April 9th. Thus, the date he mentions should be April 10th. This fact indicates that the sending of Sinhala ‘Sri’ buses to Jaffna by the Bandaranaike cabinet that though they were divisive in other labor issues, this specific act was a political trial balloon to show the spoilers among the Sinhalese constituency that they were not against to implementing the Sinhala Only Act to the letter.] On hearing this, a group of youth, led by Amirthalingam, Senator Nalliah and a youth leader, Sritharan, went to the Jaffna bus stand and removed a Sinhala Sri number plate and affixed a Tamil Sri number plate. All three of them were arrested and produced before the Jaffna Magistrate Court. The case was fixed for 15 October 1958. Jaffna Magistrate B.G.S. David sentenced them to pay a fine of Rs. 25 each and, in default, two weeks of simple imprisonment. Amirthalingam gave the Court clerk a letter asking him not to accept any money paid on his behalf, and he was sent to jail. Nalliah and Sritharan also refused to pay the fine and were jailed. On his release, Amirthalingam was taken in procession to the Muniappar Kovil where a special Pooja was held.

Between his arrest on 19 April [sic] and his trial on 15 October, many events of national significance had taken place….”

According to Vittachi, “Tamil Federalists in the north, desperately anxious to find a popular gimmick to symbolize their struggle for linguistic equity, had begun to obliterate with tar the Sinhalese character Sri which had replaced the English letters on the registration plates of motor vehicles.” This in turn, created the “ugly wave of reprisals in the predominantly Sinhalese areas.” He failed to offer a valid explanation for such a situation, other than meekly inferring “It is quite true that the use of the Sinhalese character for this purpose at a time when language was a sore point was unnecessary and provocative.”

Why the anti-Sinhala letter Sri campaign was undertaken by the Federal Party?

- Navaratnam (not an MP in 1958), one of the ranking leaders of Federal Party, had provided the reason for the anti-Sinhala letter Sri campaign, in his 1991 memoir. Here are two relevant facts, not mentioned by Vittachi. The MEP government nationalized the bus transport service from January 1, 1958. The Minister of Transport in the Bandaranaike cabinet was Maithripala Senanayake, who subsequently married a Tamil journalist lady Ranji Handy.

I provide excerpts from Navaratnam’s book below.

“The implementation of the [B-C] Pact was the responsibility of the Government, and the Federal Party waited patiently for the Prime Minister to take the necessary measures. It kept on reminding him on the need to take early steps.

In the meantime, a Department of Government decided on a scheme which gave the impression of an attempt to force the pace of implementing the Singhala Only Official Language Act. Whether the Government allowed the step as a feeler, or the Department concerned acted on its own, it is impossible to say. But it triggered a new wave of resentment among the Tamils.

The Registrar of Motor Vehicles announced a new system of assigning registration numbers to be exhibited on the identification plates of motor vehicles. The current [i.e., then prevailing] system was to have the English alphabetical letters from the name CEYLON prefixed before the numerals. Under the new system announced, the Singhala letter SRI would form an integral part of the new series of registration numbers…

The Tamil people, therefore, regarded it as an insidious attempt on the part of the Government to force the Singhala language down their unwilling throats. They considered it not only an affront to their national sentiment and self-respect, but a violation of their basic language right. They resented that they were being forced henceforth to exhibit the offending and insulting letter on their own motor vehicles, and to ride in buses carrying it.

It was, indeed, a trivial matter in itself. The people and their sole representative spokesman, the Federal Party, however, took it seriously as a clear violation of the B-C Pact. Registration of motor vehicles and assigning identification numbers would be within the purview of the proposed Regional Councils under the Pact. The action of the Registrar of Motor Vehicles was clearly an attempt to forestall it and make it impossible for the Councils to change it when they begin to function. If this was suffered to pass, there was no telling what next. The Federal Party lodged a strong protest with the Prime Minister and requested that the proposal be suspended until after the Regional Councils are established. [Note by Sachi: Italics added here, for emphasis. Though, Navaratnam accepts in the first sentence of this paragraph that it was a trivial issue, he explains that this particular Act was seen as a clear violation of the B-C Pact. Critics of the Federal Party, like N. Sanmugathasan mentioned in part 1, as well as journalists like Vittachi had not assessed the situation from the Federal Party angle.]

While the matter was under discussion between the Federal Party leaders and the Prime Minister, one fine afternoon the first bus of the state-owned Ceylon Transport Board made its appearance at the Grand Bazaar Central Bus Stand in Jaffna bearing the new number plate with the Singhala SRI. It was somewhat like a challenging call for a confrontation. Amirthalingam, MP for Vaddukoddai, leading a group of party volunteers went up to the bus and obliterated the Singhala letter by applying tar on it.

News of the event reached us in Colombo. The party president, Vanniasingham, was in Colombo at the time. After quick consultation, he rushed to Jaffna. Of course, there was now no question of any retreat. As more buses appeared at the bus stand with the Singhala SRI, batch after batch of volunteers under the president’s on-the-spot leadership carried on the peaceful campaign of obliterating the Singhala letter. They were all arrested by the police and remanded…” [Note by Sachi: Italics added to the last sentence, for emphasis.]

Vittachi’s dismissive quip that the anti Sri campaign by the Federal Party was a “popular gimmick”, has to be tempered with the Tamil point of view that, sending the buses with Sinhala ‘Sri’ register numbers by the Ministry of Transport to Jaffna was also a ‘political trial balloon’ hoisted by wily Bandaranaike’s cabinet to outsmart their Sinhalese political opposition.

The back cover of the Emergency ’58 book provides a ‘Warning’ from an anonymous pamphlet sent to Tamils. Hardly anything is mentioned by Vittachi in the text about this purported ‘Warning’. Vittachi’s final paragraph consisting of three sentences were,

“The terror and the hate that the people of Ceylon experienced in May and June 1958 were the outcome of that fundamental error. What are we left with? A nation in ruins, some grim lessons which we cannot afford to forget and a momentous question: Have the Sinhalese and the Tamils reached the parting of the ways?”

What he had identified as the ‘fundamental error’ in the above cited first sentence was that the then ruling government ignored and even spurned ‘to reserve and strengthen the rule of law and the authority of the officers who enforce the law. He was correct that the parting of ways between the Sinhalese and the Tamils had begun in 1958. During the past 60 years, pundits of all colors and both sexes (national, regional and international) had polluted the book shelves with ‘band-aid’ plans, promises. But, no remedy is at hand.

Tarzie Vittachi’s Thoughts – 25 years later after the 1983 Anti-Tamil Holocaust

In 1983, J.R. Jayewardene (the guy who played a spoiler prior to the 1958 Anti-Tamil riots) had become the President of the island. Tarzie Vittachi had gained international recognition officially, partly due to his association with the CIA-liaison (or sponsored) news media institutions. He was also leading an expatriate life. As such, his ears were far from the ground situation; thus, he was dependent on the word of mouth spread by the lackeys of Jayewardene. Vittachi contributed a commentary to the Boston-based ‘World Paper’, in which he was affiliated as an associate editor. This item was republished in the Tribune (Colombo) of November 12, 1983. I provide the complete text of this commentary below.

What is revealing is Mr. Vittachi’s cynical comments on the mentality and coverage of island’s events by the linguistically and culturally challenged ‘foreign correspondents’ variety (whom he tagged as ‘parachute artists’) in the penultimate and the final paragraphs of this commentary.

‘When Rumour Runs Riot’ by Tarzie Vittachi

We are reliving the nightmares of 1958. The same bacchanal of brutality, the same causes, the same suspicions about conspiracies plotted at home or abroad, the same unreason, the same debasement of the value of a life. The same eyes glaze with incomprehension and disbelief. Everyone deceiving themselves that ‘it can’t happen here in this lovely island of gentle smiling people’. It did. Sinhala or Tamil, people butchered, their homes and chattel put to the torch, and rumour again reigning supreme in the absence of information as it did a quarter of a century ago. Should one delve into the history of 2,000 years of conflicts between Sinhalese and Tamils, a people imbued with the same compassion that both Buddhism and Hinduism teach? The difference is that there was hope 25 years ago that the horror would teach us some lasting lessons on tolerance and mutual respect, so that, like a family after some terrible internecine quarrel, we would live peaceably again.

‘Have we come to the parting of ways?’ I had asked in Emergency ’58. That was really a prayer that the answer would be negative despite the plethora of evidence to the contrary. Now the wounds, self-inflicted are deeper and more prurient, the ugly scars are raw and will take a long time to heal. It looks hopeless now that what has happened has happened. Is it? Is it beyond the capacity of people practiced in the ways of democracy – whatever its forms – to talk things over and to work things out so that their children will not be victimized by demagoguery, however beguiling? Without that hope there is nothing in the foreseeable future except hate, unreason and violence. Is this being naïve? Well then the answer may lie in naivete.

Many years ago S.J.V. Chelvanayakam, the quite courageous, cultivated leader of the Federal Party of the Tamils, made what now seems a prophetic remark, ‘Banda’, he said to the Prime Minister Solomon Bandaranaike, ‘You are now resisting Federalism. In 20 years you will find yourself resisting separatism.’ When racial or religious tensions are relegated to benign (or malevolent) neglect they fester and poison the whole nation. All social groups – from tribes to nations – protect their individual identity. Cultural and linguistic distinctions are deep rooted in their very essence, way below the skin. The older the cultures are the more difficult it is to dissolve their distinctions by assimilation or suppression, as Enoch Powell found in England. He once said: ‘When I look into the eyes of a West Indian, I have no fear. But when I look into the eyes of an East Indian, I do have fear. The West Indians in Britain were culturally colonized; they could pass for Britons, they were Christians, English was their only language.’ Powell believed they were assimilable despite their pigmentation. Not so the immigrants from India and Pakistan, who insisted on practicing their traditional religions, eating their own food, speaking their own mother tongues, wearing their own kind of clothing and following their own mores. And thus began the phenomena of Pakis bashing in Britain.

When communalism breaks loose it creates a sort of clarity, as all polarization does. The habitual, inchoate social norm in which people living in a country refer to themselves as ‘us’ suddenly changes into a clear ‘we’ and ‘they’. ‘If war is the logical extension of diplomacy, arson and murder are the expression of communal ulcers festering under cultivated propriety. People drop their educated postures and reveal their deeper attitudes. An example of this transformation was offered by a very well-educated lady of my acquaintance in Colombo. Her reaction to one atrocity story she had heard was, ‘What a terrible thing, no? I can’t believe human being can do such things. But, after all, see what they did to us? How long can they expect us to take it, no? [Note by Sachi: Italics, inserted for emphasis, by me.] What all of us Sri Lankans lost in the re-enacted tragedy is to be found in those innocently loaded words, ‘after all’ and they. ‘The underlying implication is that beyond and beneath the knowledge that we are all human, there is another reality, a bloody home truth that tribalism is deeper than nationalism, that we who speak the same language, worship at the same shrines, count in different numbers, and many within our tribes or caste remain a clear, identifiable, and distinct group. I, for one, reject vehemently that ‘truth’; it is a false assumption, not a reasoned or even visceral truth to suppose that human beings cannot accept their biological oneness while recognizing their ecological difference. It is one of those either/or propositions, which distorts truth. Life is never about either/or but about and/and.

The first casualty in a racial riot is the truth – and by that I mean not the eternal varieties but simple, plain information. No news is NOT good news when people are in a state of shock. If there is no information people become susceptible to those who make it up. Do they invent stories from malice after-thought? Some do. But most are motivated by something much simpler, the wish to appear to be in the know, to have privileged access to ‘facts’ which others are not permitted to have. Regular news broadcasts are the only means of tempering the damage that rumours or murder, arson and rapine breeds. But, even if they don7t tell the ‘whole’ truth, they must be credible. Thirsty for news, people then look forward to the 8 o’clock broadcast, and the 12 o’clock broadcast and the 6 o’clock broadcast. The long chaotic days and the long curfew capped evenings are given a semblance of orderliness.

But what is good news for the foreign is bad for the country reported – not because the government is allergic to the truth being bruited about as is usually alleged, but because reporting of incidents taken out of context distorts reality out of recognition. And, also those distortions. [Note by Sachi: Italics, as in the original.] And, also those distortions are broadcast back to the public of the suffering county which takes them for gospel in the absence of authentic information at home, and pours fuel on the flames. This, of course, doesn’t bother the foreign correspondent, because he is concerned not with quenching other people’s fires but with pleasing his editor. The parachute artists, the foreign correspondents, gave a classic demonstration of their craftsmanship in reporting the tragedy in Sri Lanka. In they flew, braced themselves at the bars of the grand hotels and went in search of copy, deadline pressing on their minds. How do you begin to report events taking place in a foreign country about which you know little or care even less?

It takes too long even to delve into the outbreak of violence since Sri Lanka became independent. Try to set the events in perspective, in the context of the processes which brought them about. Their news editor would be bored out of their minds. How then find a story? The thing to do is to identify the guys in the white hats and black hats, the good guys and the bad guys. Simply the intricately complex relationships between two groups of people so that the reader gets the drift without understanding any of it. Bewilderment and bloodiness – the gorier the better – are good for business.

Cited Sources

Souvenir Committee, headed by A. Amirthalingam: Ilankai Tamil Arasu Kadchi Silver Jubilee Volume, 1974, published by S. Kathiraveluppillai, MP, Jaffna.

Navaratnam: The Fall and Rise of the Tamil Nation, Kaanthalakam, Madras, 1991, 344 pp.

Sabaratnam: The Murder of a Moderate – Political biography of Appapillai Amirthalingam, Nivetha Publishers, Dehiwela, 1996, pp. 88-89.

Mathew Barry Sullivan: Tarzie – Everything is about something else. Sunday Times (Colombo), Sept. 21, 1997.

Tarzie Vittachi: Emergency ’58 – The story of the Ceylon Race Riots, Andre Deutsch, London, 1958, 123 pp.