An American Nurse in Jaffna – 80 years Ago

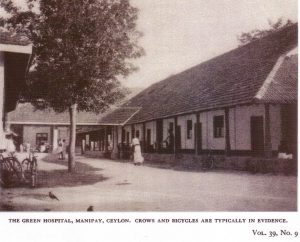

Green Hospital circa 1939

by Sachi Sri Kantha, August 30, 2019

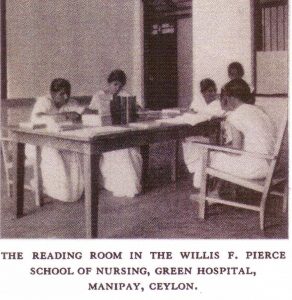

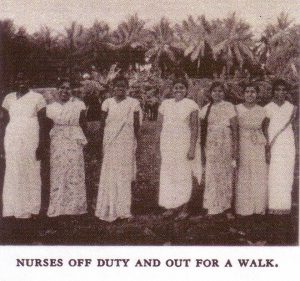

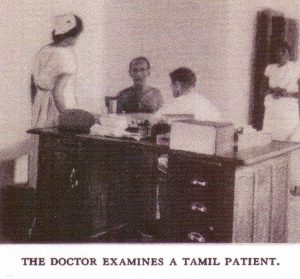

Eighty years ago, the American Journal of Nursing published a four page article of by Ms. Annette Beals, in its Sept. 1939 issue (vol.39, pages 991-994). See below. She had visited the Green Memorial Hospital in Manipay and reported to her peers in this journal on the status of nursing in Jaffna, in the then colonial Ceylon. A pdf file of this travelogue is given nearby. The article carried four period photos. These were, (1) Green Memorial Hospital, (2) Reading room at the hospital, (3) Tamil nurses on off duty hours, and (4) A doctor examining a Tamil patient.

This travelogue is not included in the compilation of H.A. I. Goonetileke’s Bibliography of Ceylon (5 volume series, 1970-1983). For my appreciative essay on Mr. Goonetileke’s scholarship [Ian Goonetileke and the anti-Tamil riots of July 1983], please check this link https://sangam.org/ian-goonetileke-anti-tamil-riots-july-1983/

Reading room at the Green Hospital, Manipay, circa 1939

I also checked that, for some reason, this short report also failed to receive an entry8f neither in the Pub Med database, nor in the Bibliography of Medical Publications relating to Sri Lanka, 1811-1976, compiled by Kamalika Pieris and C.G. Uragoda (1980). Thus, it’s my pleasure to bring this travelogue to the limelight.

Two specific observations made by Ms. Annette Beals in 1939, I cite below for reflection on the values of Jaffna society of that period.

Observation 1: “When one sees a grandmother feeding a twenty four hour old infant tea, one wonders how there are any babies living at all. I have learned, however, that giving weak tea to a new born baby does have an advantage. In order to make tea, the water must be boiled, and the baby is not being fed ordinary, un-boiled water that may be contaminated with anything from typhoid bacilli to worm cysts.”

Tamil nurses during off duty hours, circa 1939

Observation 2: “They [Jaffna people] are very conservative folk and are very much afraid that their daughters will be involved in some dreadful scandal if they come to a hospital, especially one which cares for men patients as well as women. Many of the girls themselves are perfectly willing to come if their parents will only let them.”

In my inference, the concerns of the conservative Hindu parents towards their daughters deserve sympathy as well. This was because, those who worked at the missionary hospitals (like that of Green Hospital), in addition to offering health care services, were also involved in gentle proselytizing activity as well.

An American Nurse in Ceylon

By ANNETTE BEALS, R.N., The American Journal of Nursing, SEPTEMBER 1939

WHEN I ACCEPTED my present position, all I knew about Ceylon was that it is an island off the tip of India, that it has a port named Colombo, that the romantically named city of Kandy, somewhere in the middle of the island, is often visited by tourists, and that friends had worked for a time in a section in the northern part of the island called Jaffna. This, though, is greater knowledge than that of the people who know it only as the place from which tea comes.

Doctor examining a Tamil patient, circa 1939

Jaffna is an absolutely flat, typically tropical country covered with coconut and palmyra palms. It is inhabited by Tamils, the same people that are found in South India. The southern part of Ceylon is very different in many ways and is inhabited by Singhalese. Up here in the Jaffna peninsula the metropolis is the town of Jaffna which is surrounded by many little villages closely packedtogether. In fact, they are so close that there are three villages on the five-mile road between the hospital and Jaffna Town.

The main roads are hard surfaced though they are merely overgrown winding lanes, hardly wide enough for two cars to pass each other. The other roads are a maze of narrow, tortuous dirt lanes where a stranger can become lost in two minutes. One can never see where one is going, nor catch more than a tantalizing

glimpse, here and there, of the huts and houses behind the impenetrable palmyra and coconut leaf fences that line all roads and lanes and surround the smallest yard. The only time when Jaffna’s love of privacy is not made evident by fences is when the road finds its way out into the paddy (rice) fields. Acres and acres of luscious yellow-green paddy fields make Jaffna a beautiful spot in the rainy season.

There are some very serious problems of health here, although the government of Ceylon has very successfully grappled with and overcome some others. For instance, there is no plague nor cholera and practically no smallpox, although India-only two hours by steamer at the nearest point-is teaming with all three. The quarantine and medical examinations at the two ports of entry for immigrants are very strict. Not even a coolie coming to work on the tea plantations in the hillcountry in central Ceylon can enter the country without a thorough physical examination.

The government of Ceylon has hospitals, health centers, and dispensaries scattered throughout the island, but

there are not enough of them, nor are they adequately staffed. This is especially true from the point of view of

nursing and Jaffna, tucked away off up here, at times is treated rather like a poor relation by the government. There is one good government hospital in Jaffna town and one small one on an island a mile off the coast. Otherwise, except for a few dispensaries, the thousands of village folk have no way of getting medical help and must rely on their own native system of medicine which is practised, for the most part, by quacks. So this mission hospital of about one hundred and twenty-five beds that are available to rich and poor, to men,

women, and children, and another mission hospital (three miles away) of about the same size and open to women and children only, serve a crying need in this community. Each of these hospitals receives a small grant from the government, but is otherwise entirely selfsupporting.

Though plague and cholera and smallpox do not worry us, we have enough other diseases running rampant to keep us continually on the move. The greatest of these spectres is malaria, and Ceylon is seemingly helpless. The great forest (jungle) just south of Jaffna and the thousands of acres of rice fields in Ceylon make the island a mosquito heaven. Typhoid, amebic dysentery, and scabies are other preventable diseases of which we see a great deal too much. Worms of all kinds are a problem here. Thread worms and pin worms are so common

that we pay little attention to them since the pathological conditions they produce are not very serious. But patients are constantly being treated for round worms and hookworms. The tea country of Ceylon south of Jaffna suffers more from the ravages of hookworm, however, than we do.

In some of the schools hookworm treatment is given to every pupil just like smallpox vaccinations or typhoid

innoculations. (It should be annually compulsory in all schools, but is not.) But it is seldom that they do these

wholesale clean-ups as regularly as they should. Reinfection is so common that one treatment seldom cures for good.

I do not recall a single day when the hospital has not had at least one typhoid patient and the rainy season brings a small epidemic of it every year. All the hospital staff are innoculated annually as a matter of routine. Scabies is so common that it is hardly considered a disease. Almost every child brought to the hospital has it in more or less severe form but if treatment is suggested to the parents, they beg and implore us not to, or they forbid it outright. The idea is that if we cure the “itch,” the child will probably get something worse. That

is good logic to the ignorant villager, and it is impossible to persuade him otherwise. We content ourselves, therefore, with using plenty of good soap and water and do not mention the condition to the parents unless it is so severe that the sores are badly infected.

You would be surprised at the way food is handled. We have no dietitian and no diet kitchen. Instead, there are

six long rows of sixty tiny kitchens. These are rented to the patients who never come to the hospital without the

whole family, and sometimes it seems that the whole village has come to tend the sick one. Most of the people are Hindus and have a very strong sense of caste distinction. They would not eat food prepared by us, but they believe thoroughly that the right diet is as important as the fanciest medicine we can give the patients. This being so, they usually carry out the doctor’s orders very carefully, provided what he tells them is not too contrary to their own ideas. “What food shall we give?” is asked more often than any other question. To answer, “liquids,” or “soft foods,” is not enough. One must be particularly careful to specify tea, vegetable soup, barley water, malted milk, et cetera.

At first, I was shocked when the doctor ordered a poor villager to give a patient malted milk, but I soon discovered the clever reason. The natives believe that a person with fever should never be given milk, though I have never been able to discover a logical reason for this belief. So my blessings are on the inspired salesman who came to Ceylon and convinced everyone that the creamy white powder bought in bottles is a specific for

fever if it is mixed with water and fed to the patient. One food drink, also very popular, has egg in it and those who know this will not give it at certain times because they firmly believe that egg yolk is very indigestible in any form.

Minerals, vitamins, and food values are merely words invented by the western world. The staple food is, of course, rice. The normal day’s diet consists of tea and rice cakes in the morning and a huge pile of rice flavored with curries, so hot that to us they are like liquid fire, for the noon and evening meals. When the doctor tells the patient he can eat rice, it means that he can now eat a regular diet.

The infant mortality rate is dreadfully high anywhere in the East but it is a wonder that it is not higher than it is

here. Women who are so anemic that they can hardly move around come to us for confinement.1 A hemoglobin report of 50 per cent is hardly noticed because there are so many patients whose hemoglobin is below 40 per cent and who need attention more acutely. We have seen women with hemoglobin of IO to 25 per cent much more often than would seem possible. The baby doesn’t have even a sporting chance under such conditions. When one sees a grandmother feeding a twenty-four-hour-old infant tea, one wonders how there are any babies living at all. I have learned, however, that giving weak tea to a newborn baby does have an advantage. In

order to make tea, the water must be boiled, and the baby is not being fed ordinary, unboiled water that may be

contaminated with anything from typhoid bacilli to worm cysts.

There is much to teach the folk here but, on the whole, they are far better educated than some of the other Oriental peoples. Jaffna has many vernacular schools, English schools, and “bilingual” schools. The girls have as good opportunities as do the boys, so there is really plenty of material for this school of nursing to draw from. It is still very difficult for the Jaffna people to understand that nursing is not work that only servants should do. They are very conservative folk and are very much afraid that their daughters will be involved in

some dreadful scandal if they come to a hospital, especially one which cares for men patients as well as women. Many of the girls themselves are perfectly willing to come if their parents will only let them. So teaching the parents seems to be one of the jobs of this school.

A lovely, big, new building just a year old houses the nursing school. It is well equipped with practice room, classroom, and living quarters for the girls. The possibilities and opportunities for development are tremendous. One branch of nursing that needs development more than any other is public health nursing. It is our dream one day to have a splendid group of visiting health nurses who will use the hospital for their headquarters. An interested, well-trained, and experienced public health nurse would find ample opportunity to demonstrate her executive ability in this work.

The standard of nursing in Ceylon is rising steadily and rapidly. It is going to become easier for Jaffna girls with a good education to take up nursing without fear of incurring a bad name, so more and more of them will apply for admission to the school. They are hard workers and intelligent, and they can be prepared as excellent nurses. It is always a joy to teach those who are interested and eager to learn, and the Jaffna Tamil is like that. So our hopes are great, and our aspirations high. In spite of many difficulties, we can do our bit in service to

those who need so sorely just what we are able to give.

V

1 Dr. Heiser has pointed out the problem of hookworm in Ceylon in An American Doctor’s Odyssey,

Norton, 1936, pp. 327-343.