by T. Sabaratnam, January 28, 2004

Volume 1, Chapter 27

Original index of series

Pondy Bazaar Shootout

With unbridled power concentrated in his hands, President Jayewardene set out to stifle the fledgling Tamil militancy. But the tools he used- state terrorism and weakening of the moderate leadership – were counterproductive. Police and army atrocities, in the process of frightening the Tamil people into submission, emboldened them. They drove the Tamil people into the arms of the militant groups. They helped the militant groups to gradually assume the role of protectors.

Weakening the TULF by refusing to make the DDCs effective, too, had a similar effect. The TULF, which put the entirety of its hopes and future on the success of the DDC system, lost its credibility, as it had nothing to show the people as its achievement.

Police and army pressure on the militants did to some extent debilitate PLOTE, as some of its top men like

Mariyanayagam, Ganeshalingam, Robert, Gnanasekaram, Anton, Aranganayagam, Arafat were taken into custody. But the LTTE, then smaller than PLOTE, remained relatively intact.

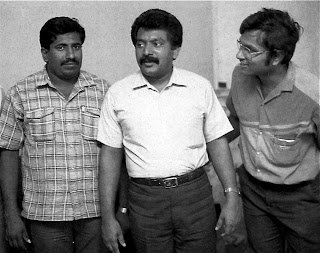

Mahataya, Pirapaharan & Yogi (l.tor.)

Pirapaharan and ten of his trusted men crossed over to Tamil Nadu on 6 June 1981, on the sixth night after Pirapaharan saw with horror the burning of the Jaffna Public Library, a blatant act of state terrorism and cultural genocide. He kept back Mahataya to watch LTTE’s interests in the Jaffna peninsula.

Uma Maheswaran stayed in his Vavuniya Camp, staged the spectacular Kilinochchi bank robbery and crossed over to Tamil Nadu with four of his confidantes on 25 February 1982, taking with him 20 packets of gold. He went to Chennai where he had established a network with the help of the Communist Party and Tamil nationalist movements.

Pirapaharan at that time was working with TELO as many of his senior colleagues had deserted him and joined Uma Maheswaran’s PLOTE. Pirapaharan, who left his home at the age of 16 to commit himself totally to struggle for the freedom of the Tamil people, was pained and in his interview to Anita Prathap in 1984 called the desertion ‘betrayal’:

Q: “Which was your most frustrating moment of your life?”

A: “I cannot pinpoint such a moment in my life. But the most frustrating aspect has been the betrayal of some of my trusted friends: those who pretended to be sincere to the cause. But turned out to be self-seeking opportunists.”

_112712023345.jpg)

Kittu

Pirapaharan went to Madurai where he stayed in the camp. He asked Kittu and Ponnamman to stay in Madurai and proceeded to the rented house at Varasalavakkam, on the western outskirts of Chennai, where Balasingham and Adele were living during their second spell in Tamil Nadu in 1981. Adele in her book “The Will to Freedom” records one of Kittu’s youthful pranks in Madurai. Dressed like a Brahmin and wearing a white thread that resembled the sacred thread (Poonool) he went to a non-vegetarian restaurant and ordered mutton curry and fried chicken and ate them with relish, astounding the waiters and the owner.

Adele also provides thumb-nail sketches of the cadres who lived in their Varasalavakkam home. Baby Subramaniam, who joined Pirapaharan soon after he formed the LTTE in 1976 and is currently in charge of education in the Vanni administration, was a mild mannered person who never indulged in gossip or personal power struggles. He was a walking encyclopedia of the history of freedom struggles and of the LTTE. He always carried with him an old bag, full of papers and books dealing with freedom struggles. Being a strict vegetarian, he would eat his rice meal with five of six fried curd-chillies (moor mulakai).

Moor mulakai

Nesan (Ravindran Ravithas), who gave up his medical studies to join Pirapaharan, was then his close confidante. He later dropped out and is living in a foreign country. Shanker was another. A young man with an athletic build, he used to go out of the house every morning to do his running exercise. Shankar helped Rahu for some time to look after Pirapaharan’s security. Rahu was Pirapaharan’s chief bodyguard for many years. He was later expelled from the LTTE for violating the rules. Pandithar was the other member of the Varasalavakkam household. Pandithar, a chronic asthmatic, never permitted

his disease to obstruct his political activity. He was killed in the army roundup of the Atchuveli camp in January 1985. Sri Sabaratnam who later became the leader of TELO also lived at Varasalavakkam because of the TELO- LTTE working alliance.

Pirapaharan was a regular visitor. He lived in one of the three rooms allocated to the two Members of the Legislative Assembly (MLA) of the Tamil Nadu Kamaraj Congress (TNKC) of which Nedumaran was the leader.

Balasingham & Adele

Moves were afoot at that time to form a new organization by integrating the LTTE and the TELO. Sri Sabaratnam, who became the leader of the TELO after the arrest of Thangathurai and Kuttimani, supported that move enthusiastically, saying combining the skills and the resources of both organizations would strengthen and widen the freedom struggle. Two objections were raised by senior members of the LTTE. Firstly, they did not want to give up the history of the LTTE.

Secondly, they feared that Uma Maheswaran, who earlier had claimed the leadership of the LTTE, would reassert his claim.

Sri Sabaratnam was not happy, but agreed to postpone the move. That move failed because, by the middle of 1982, Pirapaharan decided to drop the working alliance with TELO and function on his own.

Baby Subramaniam, later, reasoned Pirapaharan’s decision thus: Pirapaharan had had enough trouble with people who would debate on everything endlessly. He, an action oriented person by nature, abhorred this debating which resulted in delaying or even abandoning action. He believed that there should be a single leader and his study of successful revolutions and freedom struggles convinced him of this. He wanted the freedom struggle of the Tamils to succeed, and for that to happen, there should be a monolithic organization under his leadership.

Pirapaharan instilled in his cadres the habit of rising early and performing their physical exercises. They eat their breakfast around 8 a.m.; rotti, thosai or occasionally string hoppers with coconut sambol or dhal curry. Around 9 a.m. Balasingham, Adele, Pandithar and others, who volunteered to join trek in the searing sun to the bus halt on the main road about a kilometer away, wait for the bus. They wave the grey-green bus to a halt and travel to the Peroor market to buy that day’s provisions, fish and vegetables. Balasingham, a hard bargainer, does the bargaining. He always buys the freshest fish at the cheapest price, says Adele.

Pandithar

They then cook their main rice meal. On Pirapaharan’s insistence, everyone had become a good cook, but Adele says Pandithar was the best. So, he functioned as the chief cook. Bala took upon himself the messy task of cleaning and cutting the fish. Once that was over, he would sit on the sack of rice kept in the corner of the kitchen and crack jokes. By the mirth and laughter Adele surmised – she did not know Tamil then – they would have been dirty jokes. Adele peeled the annoying small onions, Ragu cut the vegetables according to Pandithar’s instructions, Shankar helped Ragu, Nasen scraped the coconuts squatting on the ground, Sri cooked meat, his specialty, whenever it was cooked and Pirapaharan joined in to cook his favorite chicken curry dish.

After they finished cooking, they took a wash, sat on the mats cross-legged, and ate their lunch. Then they took a nap

while Pandithar toiled writing that day’s accounts and balancing the organization’s budget. In the evening, they went either

for a film or to the beach. Pirapaharan preferred to watch English films, particularly war films. If they did not go out they would gather on the flat cemented roof (moddai madi) and discuss political developments in Sri Lanka and India and plan their strategies. If the discussion was laced with laughter, Adele knew that Bala was entertaining them with his dirty jokes.

When Pirapaharan was away, they played cards, which he had prohibited. If he suddenly returned while they were playing, he would rebuke Bala for encouraging the boys down the wrong road. Smoking and drinking were strictly prohibited.

Pirapaharan insisted that expenses on the cadres should be kept low but they should be fed and looked after well. “They had sacrificed their parents and the comforts of family life for the sake of the freedom struggle. They should be given good food and at least the minimum comforts,” Pirapaharan repeats endlessly. He did not permit any waste. The daily expenditure allowed for food for each cadre was ten Indian rupees. The cadres were allowed two sets of clothes. They should wash them daily and wear them clean. New clothes were bought for Tamil New Year and Dipavali. They should have their hair cut and shave regularly. Pirapaharan detested his cadres looking shabby. Pocket money for the cinema was given once a week.

Raghavan

Pirapaharan, Ragu, Ragavan, Pandithar, Shankar and Baby carried revolvers. They had their ‘big guns,’ too. Adele was the first woman in the movement to carry a revolver. She carried it in her handbag. She was told to protect herself and Bala with that weapon for Bala never carried weapons.

Adele in her book “The Will to Freedom” recounts the training she was given to handle weapons. She says she was taken to a coastal area a few kilometers south of Chennai. The target was set up inside a young cypress tree plantation. Ragu and

Pandithar went away to bring the guns from a hidden place. They returned with two very long newspaper-wrapped parcels.

They were automatic rifles.

Adele was first taught the use of the revolver. Pirapaharan instructed her how to fire the deadly weapon. He then demonstrated it. “He then handed me the weapon,” Adele says. “I, of course, felt clumsy handling it… I aimed and hit the target at least once out of six shots. We then turned to the automatic rifle and that was an awesome experience. The power of the recoil nearly made me to drop the weapon.”

Pirapaharan and his cadres were very careful during the practice sessions. The ammunition was costly and extremely difficult to get. Each bullet cost 25 Indian rupees. Each cadre was given one or two rounds of ammunition per week for shooting practice. That made the cadres use the ammunition very carefully and try to achieve maximum accuracy with their aim. That gave birth to Pirapaharan’s weapons policy: wrest them from the enemy. Pirapaharan repeated to his cadres like a mantra: Get the weapons from the enemy, Never lose a weapon to the enemy. The wresting of even a simple revolver was a matter for celebration.”

“Pirapa,” whispered Kannan

Pirapaharan and Uma Maheswaran loved thosai, especially the masala thosai prepared at a restaurant near the Pondy Bazaar railway station. Both were frequent patrons of that restaurant. On 19 May, Uma and Kannan ate their dinner there and came out to go to Pavalar Perumchithnar’s house where they had stayed since crossing over to Tamil Nadu on 25 February. That evening Pirapaharan and Ragavan saw a Hollywood film at a nearby cinema hall and walked to the restaurant for dinner. Uma was busy starting the motorcycle, on which he was seated, and Kannan was climbing onto the pillion. Kannan saw Pirapaharan.

“Pirapa,” he whispered to Uma.

Uma’s hand dipped into his trouser pocket to fetch the revolver.

Pirapaharan, too, had spotted Uma and he whipped out his revolver.

Agile and smart, Pirapaharan fired first, but Uma ducked and drove off in his motorcycle. Six shots rang and four bullets

pierced Kannan’s legs, an accolade to Pirapaharan’s marksmanship, and Kannan fell on the road bleeding.

The crowd on that busy road was shocked and a few sturdy youths chased Pirapaharan and Ragavan, who ran towards the station. Finding they were running towards the Pondy Bazaar police station, they turned back and ran into a human wall of shouting men. Inspector Nandakumar, realizing that the sound he heard was from a revolver, ran to the road with his men.

The crowd overpowered the two fleeing men and handed them over to the police.

The police acted fast. They dragged the two men, beating them all the way, to the police station. They dispatched the wounded Kannan to Royapettah hospital.

For the Pondy Bazaar police, use of a revolver was totally unusual. Underworld gangs often settled their grudges in that area. They used knives, iron rods and bicycle chains, but never a gun. Nandakumar was stern. Uma was caught after a week, on 25 May, while waiting at a railway station. A constable walked up to him and demanded him to show his identity papers. Uma refused, argued. When the constable tried to arrest him, Uma resisted and pulled out his pistol. It went off accidentally. The constable knocked him down, overpowered him and arrested him.

Pirapaharan, Ragavan and Uma were taken to the Foreshore Police Station and locked up in separate cells like common criminals.

Pirapaharan gave his name as Karikalan and Uma his name as Muhunthan, their Iyakkap peyar (the name by which they are known in the movement). The Tamil Nadu police treated them as common criminals and slapped the charges of attempted murder and violation of the Indian Explosives Act and the Arms Act on them. When their real identities were known, it was shocking news for the Tamil Nadu Police and a prize catch for Sri Lanka. The Tamil Nadu police suddenly turned courteous and treated them with respect. In Colombo, there was thrill, elation. The news was conveyed to Deputy Defence Minister D. B. Werapitiya and to President Jayewardene. Werapitiya summoned the National Security Council, which decided on three actions: to request India to deport Pirapaharan and Uma; to send a delegation headed by Inspector General of Police Rudra Rajasingham to negotiate deportation and to offer a reward of one million Sri Lankan rupees as a reward for making the arrests.

State media, particularly the Daily News, was told to give maximum publicity to the decisions of the National Security Council. Daily News and its two sister morning dailies Dinamina and Thinaharan led with the sensational story about the arrests. The story quoted an un-named senior policeman as saying: “These arrests are a very significant break-through, the best we’ve had in years.”

I was at the News Desk when the Defence Ministry phoned the story. There was joy in the News Desk. It quickly infected the whole Editorial Department and the entire Lake House. Members from other departments flocked to the News Desk to get more details. A driver, Ariyaratne, said with a sigh of relief: “The problem is over.”

The Daily News was told to play up the story and make up a case for the deportation of the three arrested militants. The Defence Ministry gave the fodder for the campaign with a press communiqué stating that Pirapaharan and Uma Maheswaran were fugitives from justice. Pirapaharan was wanted for 18 murders and two bank robberies and Uma Maheswaran for nine murders and a bank robbery. Weerapitya announced a one million Sri Lankan rupee reward to the Tamil Nadu police for arresting the two militant group leaders.

The reward story was picked up by the Indian news agencies. Tamil Nadu Chief Minister M. G. Ramachandran was

immediately informed of it. He summoned Tamil Nadu Inspector General of Police K. Mohandas and told him to treat Pirapaharan and Uma Maheswaran leniently. He said in choice Tamil: “Paiyangal visayathil konjam parthup po appa” (Be a little considerate in the matter concerning the boys). Mohandas replied they had decided not to accept the reward announced by Sri Lanka and added: “We are only interested in the law and order aspect of the problem. We only want to prevent Chennai from becoming another Chicago.”

The Daily News backed up the news stories with an editorial urging India to deport Pirapaharan and Uma Maheswaran. The editorial was a sermon to India on how Big Brother India should behave towards its little neighbour. It dug out the precedent of the Karunanithi government agreeing to deport Kuttimani in 1973 when he was arrested in India on a charge of smuggling. Sri Lankan police flew to Chennai and brought back Kuttimani handcuffed.

Rudra Rajasingham

The Sri Lankan government sent a delegation headed by Rudra Rajasingham to Chennai and Delhi to negotiate with the state and central governments for the deportation of Pirapaharan and Uma Maheswaran. He broke his journey in Chennai and had a meeting with Mohandas. His request to see the two militant leaders was granted. The delegation was taken to

the Foreshore Police Station and shown Pirapaharan and Uma Maheswaran locked up in high security cells. On his return Rudra Rajasingham told the Colombo media that the two militant leaders were locked up like common criminals. What the Sri Lankan IGP was not told about and failed to observe was the respect with which the two leaders were treated by the police.

LTTE Chief Velupillai Prabhakaran (centre) with his father (from left) Thiruvengadam Velupillai, mother Parvathy, wife Mathivathani and son Charles Anthony. (New Indian Express, Reuters)

The news of Pirapaharan’s arrest generated shock waves in Jaffna. Pirapaharan’s father, Velupillai, retained Chandrahasan, the lawyer son of Thanthai Chelvanayakam to watch the interest of Pirapaharan. He rushed to Chennai and met Diravida Munnetra Kalazham (DMK) leader Muthuvel Karunanithi, who was out of power. But Karunanithi continued with the electoral alliance DMK had with Indira Congress. He instructed his parliamentarians in New Delhi to inform Prime Minister Indira Gandhi about the danger of deporting the two militant leaders to Sri Lanka. “They would be killed,” Karunanithi warned her.

Kittu, Ponamman and Pulendran rushed to Chennai from their Madurai Camp. They held a secret discussion with Pandithar and others then staying in Chennai. They decided to get on the roof of Chennai’s tallest LIC building and threaten to jump from it if Pirapaharan was not released.

Baby Subramaniyam, the eldest of the LTTE cadres and the most knowledgeable, shouted at them in fury when he learnt about their plan. “Are you all mad?” he screamed. “Leave that to me. I will deal with that matter. I will get him out somehow or other.” Baby decided to utilize the elaborate network of sympathizers he had laboriously built.

An unassuming public relations man, Baby spent most of his time in meeting Tamil Nadu politicians, scholars, Tamil activists and even leading businessmen and philanthropists and had won them over to the Sri Lankan Tamil cause. P. Nedumaran, leader of the Tamil Nadu Kamaraj Congress, was the foremost among them. The wiry, tall Nedumaran was originally in the Indian National Congress and, when it split into two factions, he joined the Indira Gandhi faction. Later, he formed his own party, the Tamil Nadu Kamraj Congress. Baby Subramaniam met Nedumaran and requested his assistance to get Pirapaharan released.

P. Nedumaran

Nedumaran, who admired the courageous deeds and the deep commitment of Pirapaharan, had wanted to meet the young Sri Lankan Tamil freedom fighter. He had asked Baby several times to arrange a meeting. Baby had evaded it, saying that Pirapaharan was in Jaffna. Now he could not evade. He took Nedumaran to the Foreshore Police Station and, when he saw Pirapaharan, Nedumaran was astonished. He had seen him in his room in the legislator’s hostel.

Pirapaharan apologized. “I am sorry. I never told you who I was,” he said.

Nedumaran remembered seeing Pirapaharan in Jaffna when he visited that town in 1981. He looked hard at Pirapaharan for a few minutes and said: “Did you come and see me with some boys when I came to Jaffna last year?”

Pirapaharan admitted that he had.

“Why din’t you tell me your name?”

Pirapaharan explained that the police and the army were after him and police detectives were among the group of boys who went to see him. “If I had told my name I would have been arrested then and there,” he said.

Nedumaran was not annoyed. He realized how careful Pirapaharan was about his security. He also realized how bold he was. His admiration of Pirapaharan grew. He conveyed his feeling to Pirapaharan and told him not to worry. He assured him that he would do everything possible to get him released on bail. He also admonished Pirapaharan for getting involved in a shootout in a foreign country.

“Why are you fighting among yourselves?” Nedumaran queried. “Why can’t you be together? Your infighting is making it difficult to organize support to your struggle.” He advised Pirapaharan to patch up his differences with Uma.

Nedumaran kept his word. He convened an all-party meeting at the TNKC office on 1 June. Karunanithi informed him that he would not attend the meeting as he had already done the needful. MGR sent a representative to the meeting. All major political parties in Tamil Nadu participated in the meeting. Baby attended as an observer.

Three decisions were made at the meeting. The first was to urge the Tamil Nadu government not to agree to deportation. The second one was to urge the central government to turn down the Sri Lankan request for deportation. They also decided to launch a campaign in support of the Sri Lankan Tamil freedom struggle.

Indira Gandhi had by that time worked out her strategy. The option paper her experts had prepared in 1980, soon after she was re-elected to office in January that year, nearly three years after her defeat in the March 1977 parliamentary election, suggested the use of Tamil militancy as a tool to weaken Jayewardene and destabilize his government.

Indira Gandhi, aligned firmly to the Soviet block in those days of the cold war, was disturbed with Jayewardene’s pro-American tilt and his gradual shift into the Israel- Pakistan- China orbit. Her hope that Sri Lanka would get out from under American influence once Sirimavo Bandaranaike returned to power in the mid-1983 parliamentary election had been shattered when Bandaranaike was deprived of her civic rights. The only option then left for India was to destabilize Jayewardene by making use of the growing Tamil militancy.

Arular of the EROS who was in Chennai at that time told me of a secret meeting he had with the ambassador of the Soviet Union in New Delhi. Arular said he urged the ambassador to persuade India not to deport the guerrilla leaders. The Soviet envoy’s reply was: Don’t worry. Be with India. Indira Gandhi will look after you.”

Indira Gandhi looked after Pirapaharan and Uma Maheswaran. One day in mid-June, two officials of the Research and Analysis Wing (RAW) walked into the Foreshore Police Station to meet Pirapaharan. They introduced themselves as Indian Central Government officials and questioned Pirapaharan about his activities and about the LTTE.

They talked sympathetically about the problems of the Sri Lankan Tamils and informed Pirapaharan that India would be in a position to help the freedom struggle. They then asked Pirapaharan whether the LTTE would be in a position to assist India. From the questions they asked about the Trincomalee harbour, Pirapaharan knew India was up to something.

The second meeting the RAW officials had with him a few days before his release on bail on 6 August helped Pirapaharan, a keen observer of political developments in Sri Lanka and India, to piece together the emerging trend and spot the obstacles that development would place on the path of the freedom struggle of the Sri Lankan Tamils.

Next: Chapter 29. The Indian Interest

To be posted on Feb.4