by T. Sabaratnam, March 31, 2004

Volume 1, Chapter 34

Original index of series

Eyewitness Account

I was in Trincomalee on 27 November 1982 with Daily News presidential reporter Norton Weerasinghe and photographer Sena Vithanagama to cover the foundation-laying function of the Mitsui Cement Factory the next morning. We met Trincomalee Member of Parliament Rajavarothayam Sampanthan at his home on 28 November morning to arrange the use of his telephone to send the report of the event to the Daily News.

Obtaining telephone calls from provincial towns was difficult those days and only a few top government officials, police, commanding officers of armed services and parliamentarians enjoyed a direct dialing facility. Others had to go through the telephone exchange, which meant several hours of waiting. Peter Balasooriya of The Sunday Island had made arrangements with the Trincomalee Government Agent, Jayatissa Bandaragoda, one of his important contacts, thus forcing us to make an alternative arrangement.

Sampanthan had just returned from a meeting with President Jayewardene who had come to lay the foundation stone when we met him. “I thanked him for canceling the Cadju Plantation Project and briefed him about a plot to eject the poor Indian Tamils settled by Gandhyam in Vavuniya, Trincomalee and Batticoloa. The President was very accommodative,” he said.

Sampanthan also told us his worry about moves by Cyril Mathew and Gamini Dissanayake to convert Trincomalee into a Sinhala-majority province. Mathew’s mission, he said, was to discover ruins of Buddhist temples and restore them and settle Sinhala peasants around them. Gamini Dissanayake’s mission was to get state corporations to acquire vast extents of state land and settle Sinhala families in them. “Both are busy implementing the government’s agenda to make Tamils a minority community in Trincomalee,” Sampanthan said.

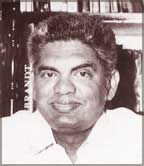

R. Sampanthan campaigning 2004

The Sinhala-Buddhist crusade to convert Trincomalee, a Tamil majority district, into a Sinhala majority area, as I pointed out in Chapter 33, was started by D. S. Senanayake. Since his time Sinhala settlements were established and Buddhist temples built along all roads connecting Trincomalee to the rest of the country. That was the answer Sinhala-Buddhist governments gave to the Tamil attempt to make Trincomalee the capital of the Tamil homeland.

The Sinhala- Buddhist plan was given added thrust since the Federal Party demanded the proclamation of the ancient Hindu temple Thirukoneswaram, situated inside Fort Frederick, a sacred area. The demand was made in 1965 by Murugesu Tiruchelvam, a Federal Party minister in Dudley Senanayake’s National Government.

Buddhists objected to the demand on the basis that the fort was the site of an ancient Buddhist temple, Gokanna Vihara, mentioned in the Mahavamsa. The Buddhist chronicle mentions Gokanna Vihara as one built by King Mahasena in the 3rd Century AD on the north-eastern sea coast. No trace of it, archaeological or otherwise, has been found. However, former archaeological commissioner Prof. S. Paranavithana, interpreted the 12th Century donative inscription written in Sanskrit found in the Hindu temple premises as proof that the vihara existed there.

The inscription merely records the visit of Prince Godaganga Deva to Gokarana. The Sinhala academics, indulging in their usual etymological trickery, an art they employ to serve the government agenda and Sinhala chauvinism, have concluded that the historic vihara existed in the Trincomalee fort premises. (For details refer to Sri Lanka Arrogance of Power, Page 76).

In their quest for Buddhist ruins Mathew’s men – Piyasena and his officials – were not worried whether the ruins were of the Mahayana Buddhism propagated by Tamil Buddhists or not. They were also not concerned whether the inscriptions found among the ruins were written in Sanskrit, the language of Hinduism or not. They claimed everything belonged to the Theravada Buddhism they themselves professed.

Thirukoneeswaram Temple

The governments since the mid-sixties had appointed Sinhalese as the Government Agents of Trincomalee. That facilitated the government to implement its agenda. Some of these Government Agents were honest and fair-minded men. Others implemented the government agenda by fair or foul means. The second category dominated the scene during Jayewardene’s reign.

Jayatissa Bandaragoda was the government agent of Trincomalee during 1978 to 1983. During his time, Sinhalization of Trincomalee was speeded up. Vast extents of land were acquired by state institutions and Sinhala families were settled on them. A long stretch of 5000 acres along the Colombo Road was brought under the Ports Authority. Thousands of acres of state land was allocated to the Tourist Board, the Petroleum Corporation and other state institutions.

Sampanthan told me he thanked Jayewardene for canceling the proposed Cadju plantation in Thiriyai, north of Trincomalee. Thiriyayi is a Tamil village with a long history. Neelapanikkankulam, a tank near the village was renovated in the 1940s and the villagers were cultivating rice in the land irrigated by it. But their ownership of the fields was not regularized by the issue of permits, an administrative mistake. Bandaragoda’s officials discovered that defect and in 1980 ordered the farmers to quit the land, saying 2000 acres of their land was being allocated to the Cadju Corporation for a cadju cultivation project.

When informed of this Sampanthan went to Colombo and met Plantation Industries Minister M. D. H. Jayawardena. The minister expressed shock when Sampanthan told him that they were planning to plant cadju in irrigated rice fields. Cadju, which does not require much water, is planted on marginal land.

“Who gave this order?” Sampanthan demanded.

M. D. H. Jayawardena apologetically said: Order had come from the very top.

That was how ministers and officials refer to the orders given by the President.

“I am helpless. You talk to the big man,” M. D. H. Jayawardena said.

Sampanthan met President Jayewardene. He presented the matter in a way that would prick his conscience. “Forget about the Tamils and the Sinhalese. Would you like to go down in history as the first head of state who planted cadju in paddy land irrigated by a large village tank?”

President Jayewardene ordered the cancellation of the project. In the initial years of his reign, President Jayewardene wanted to go down in history as a just and beneficial ruler.

Let me relate here, as a senior journalist, an order the Daily News received from President Jayewardene. He wanted each of his speeches reported verbatim and in the order he delivered it. The Editor protested. “We are a newspaper. Not a Hansard,” he said. “If we report the way you deliver, the real story will be buried at the bottom.” President Jayewardene’s reply was: “I am not worried about the story. I want my speeches to go down in history.”

That is how my colleague, Norton Weerasinghe, a reputed court’s reporter, was made the Presidential Reporter. His job was to take down the President’s speech, take the proof to the President and get his OK. Naturally, the report missed early editions and sometimes was held back for the next day.

Cashew nuts & fruit

Sampanthan said President Jayewardene’s cancellation order was carried out. His experience with Gamini Dissanayake was different. When the Mahadivulwewa colonization scheme was started with European Community funds, Sampanthan met Mahaweli Development Minister Gamini Dissanayake and told him that was a predominantly Tamil village known by the name Periyavilankulam and requested the cancellation of the scheme. Gamini Dissanayake accepted Sampanthan’s plea and in his presence gave a written order canceling the settlement. Sampanthan said he learnt later, Dissanayake had told his ministry secretary, Nanda Abeywickreme, to telephone Trincomalee Government Agent Bandaragoda to expedite the settlement so that it would be a fact accompli when the cancellation order reached him.

“This is the type of people with whom Tamils had to deal,” Sampanthan said.

The second matter Sampanthan brought to the notice of President Jayewardene was the media propaganda build up against Gandhyam. That very morning The Sunday Island and Weekend had carried on page one similar stories on the Gandhyam movement. The Sunday Island used the story written by Peter Balasuriya as its lead under the headline: Red Barna, Gandhyam Movement to be probed. It read:

Informed sources said that President J. R. Jayewardene will personally look into the activities of Redd Barna, now involved in community work in the Batticoloa district. The investigation follows a request from Minister K. W. Devanayagam. The minister, it is understood, referred to the work of Redd Barna in the Batticoloa district and Gandhyam in the Jaffna district and wanted them investigated…Regarding Gandhyam, the Minister of Social Services has been asked to make inquiries and submit a report to the Government…

The Weekend story was also written in a similar vein by Ranil Weerasinghe and Jennifer Henricus. Their opening paragraph read:

The Weekend reliably understands that a probe was ordered by President J. R. Jayewardene after K. W. Devanayagam raised the matter at a high level meeting. The organization which is Scandinavian-based is being probed by the Ministry of Plan Implementation under President Jayewardene and the other operating in the north by the Minister of Social Services.

K.W.Devanayagam

Sampanthan told me that he telephoned Devanayagam in the morning and he had denied raising the matter in any meeting. “Maybe, my name is being used to make the story appear more plausible,” Devanayagam had said. He did not contradict the story because he thought that was the work of President Jayewardene.

“I told President Jayewardene that there was a planned build up to crush Gandhyam. I told him Gandhyam was doing an admirable job by giving poverty-stricken, emaciated people a new self-respect. I invited him to go with me and see the work Gandhyam was doing. Jayewardene declined the invitation saying: If you say, so I accept it. There is no need for me to go.”

Sampanthan said Jayewardene’s rejection of his invitation served as an indication that he had made up his mind to wipe out Gandhyam and subsequent events proved his surmise correct.

Burning of Boats

I was again in Trincomalee on 2 June 1983 when organized Sinhala fishermen attacked Tamil fishermen. I was covering the opening of a new school building by Fisheries Minister Festus Perera at the prosperous Sinhala village of Samudrapura started by the Jayewardene government, when a distressed M. Selvarajah, trustee of the Thirukoneswaram temple, rushed in. He saw me and came near and whispered: “Saba, trouble is starting. They have burnt boats of Tamil fishermen last night.” He reported the matter to Festus Perera and asked him to use his influence to prevent a major calamity.

I was able to feel the mounting tension since morning. People were gathered in small groups intensely discussing the developments of the previous day. I overheard remarks like ‘breaking of heads’ and ‘teaching the Tamils a lesson.’ These two phrases had gained wide currency during those days, the first attributed to Lalith Athulathmudali and the second to the ‘the very top’ man.

The Fisheries Ministry was not in my beat, but Festus Perera was. He was at that time tasked by President Jayewardene to build contacts with the Jaffna fishing community and the Catholic Church. Festus Perera was one of Jayewardene’s trusted lieutenants. He was with Jayewardene when he clashed with Dudley Senanayake in 1972. Jayewardene had the noble quality of looking after those who stood with him during lean times. He rewarded Perera by appointing him the Minister of Fisheries when he came to power in 1977. Covering the ethnic conflict being my major assignment, I kept in close touch with Perera.

I joined the media group that left for Trincomalee on 1 June 1983. When our van entered Kurunegala town in the afternoon a group of black-shirted youths jumped onto the road and signaled the driver to halt. The driver drove straight toward them and they jumped back. We saw an unruly mob looting Tamil shops and burning them. We saw Tamil men clubbed by a screaming mob. My Sinhala colleagues stood around and shielded me from the angry glance of an unruly mob that searched for Tamils. When our vehicle snaked out of the town, my colleagues blurted out in joy: “We have saved Saba.”

Kurunegala was one of the fifty-odd cities countrywide that dealt collective punishment to the Tamils for the killing of two air force men that morning in Vavuniya town. Four air force personnel went in a jeep to the vegetable market to buy vegetables. U. L. M. Perera and W. A. Gunasekera stood guard near the jeep, while the others went into the market to do the purchase. Four PLOTE gunmen who had waited for them lobbed a hand grenade and then cut them down with gunfire. Then they snatched the weapons and ran.

The army retaliated in the afternoon. Army personnel in civilian clothes rode in army trucks to the Gandhyam Farm at Kovilkulam, about two kilometers from the town, destroyed the crops and huts and set fire to farm buildings and vehicles. Three tractors and a van were burnt. Terrified farmers hid themselves and saved their lives.

Selvarajah told me the burning of the boats belonging to the Tamils was instigated by the armed forces. “The armed forces had still not come into the open. They are getting Sinhala hoodlums to give the Tamils the works,” he said.

I saw such an operation on the night of 3 June in the heart of the Trincomalee town. Our media group was in the city when we heard that the army was searching Mansion Hotel in the main Street for explosives. We rushed to the place to cover the story. When we reached the place the army had completed its search and they told us that they had found nothing. We were disappointed that there was no story.

But we got a more thrilling story a little later! The army moved on to a nearby building and searched it. They took with them the two policemen guarding the Mansion Hotel. Then we saw a mob coming out of the Market Square. They entered the hotel and smashed up everything they found. Then they poured petrol and set fire to it. We learnt that that hotel was the property of former Trincomalee Member of Parliament B. Neminathan.

From then the number of attacks on Trincomalee Tamils began to mount. An environment and regulatory framework for systematically organized attacks on Tamils had already been created. I have already mentioned the cold-blooded murder of Sabaratnam Palanivel, a young van driver of Valvettithurai. Palanivel transported a group of relatives on 30 May to Point Pedro to enable them to catch the early morning Trincomalee bus. While he was passing the Valvettithurai Army Camp around 4.30 a.m. Corporal M. Wimalaratne, who was on guard duty, shot him dead. Later, an army truck was run over the dead body.

Wimalaratne was arrested and produced before the Point Pedro Magistrate, the last time an army offender was brought before the judiciary. This, and the earlier Navaratnarajah inquest, irritated the army and the government. Jayewardene followed his normal practice of getting one of his henchmen to raise the matter in either the UNP Working Committee, parliament or the government parliamentary group and then act on it. He did that to show the country and the world that he was acting under pressure. In this instance, he got the UNP Working Committee to call upon him to put into effect all the regulations under the Public Security Ordinance to suppress terrorism. The Island and the SUN and their Sinhala sister papers took upon themselves the role of creating the public opinion necessary for the introduction of drastic powers.

Lalith Athulathmudali, who acted throughout the Jayewardene reign as the government spokesman, provided the media with the material. He was what journalists call the newsman. He knew what news was and what was not. He knew how to manipulate the media for the government’s benefit. He was also media friendly. He had cultivated the friendship of all editors and selected talented reporters in all print and electronic media institutions. Norton Weerasinghe and myself were his men in the Daily News. To his men he gave his private telephone number. At that number they could contact him at 5.30 a.m. Norton and myself joined him at breakfast every Tuesday. He chose Tuesday because he could give us the important matters that would be discussed in Wednesday’s weekly cabinet meetings.

Lalith Athulathmudali

One day, while we were at breakfast, Lalith gave Jennifer of the Sun an interesting story. “That’s not for you,” he said after giving her the news. “Daily News is our paper. Readers will take anything printed in the Daily News with a pinch of salt. So I give the state media factual stories and the ‘independent’ media the propagandist stuff.” Lalith was a past master in flying kites to test public opinion and planting propagandist material to create the environment for government action.

On 3 June 1983 the Defence Ministry announced:

The armed forces and the police in the North are to be given legal immunity from judicial proceedings and wide-ranging powers of search and destroy.

The Defence Ministry communiqué which contained this announcement said:

Under such circumstances soldiers were compelled to react as during a war particularly in their role of fighting armed terrorists who had no compunction about killing servicemen or members of the public. In view of this it has been felt that police and the servicemen in the north should be given the freedom of the battlefield rather than having their morale sapped through conflicts with legal niceties. This is not a peacetime situation and the police and the services must be provided with adequate safeguards when attempting to control the problem.

The new immunity was contained in Emergency Regulation 15A of 3 June 1983, which allowed the security forces to bury or cremate the bodies of people shot by them without revealing their identities or carrying out inquests.

The militants answered these tough regulations with their own message: they shot dead Thilagar, who contested the municipal election as a UNP candidate defying the LTTE ban. Thilagar, a Jaffna Hospital employee, was shot dead at 6.15 a.m. on 4 June, barely 12 hours after the promulgation of the stringent laws, signifying the determination of the militants to proceed with their armed struggle.

The Civil Rights Movement sent a telegram to President Jayewardene protesting against the tough measures. It was signed by Kurunegala bishop Lakshman Wickremesinghe, the president of the CRM, and its secretary, Desmond Fernando. It said all measures taken by the government should guarantee that all persons are dealt with by due process of the law and in keeping with the fundamental principles of justice. Otherwise the government will be flouting the principles of justice that are vital to democracy in the very act of claiming to defend democratic institutions.

The new regulations not only emboldened the security forces, but also the Sinhala extremist forces and hoodlums countrywide. Attacks on Tamil homes, shops, temples and institutions increased. In the northeast, particularly in Trincomalee, where curfew had been clamped, the situation was grisly. Several bomb attacks were reported in the first ten days of June, which resulted in one death.

Tamil newspapers published harrowing accounts of attacks by organized Sinhala thugs during curfew hours. The security forces which provided ‘security’ to the thugs shot the Tamil victims who fled the scene of attacks for violating the curfew!

Security forces, some stories revealed, rounded up the youths of the Tamil villages outside the town during daytime and took them away for ‘investigation.’ Gangs of thugs attacked the villages during the nights, pillaging, burning and raping.

The situation worsened in the north and in Trincomalee in the second half of June. In the north soldiers fired on a passenger bus proceeding to Jaffna, killing the driver and injuring several passengers. They then chased the passengers and burnt the bus. The press in Colombo printed the army plant that the terrorists had attacked a civilian bus. Amirthalingam told Parliament the facts the injured passengers had told him and added that the security forces had killed six persons during the first three weeks of June.

The situation in Trincomalee was worse. That disturbed the Tamils in Sri Lanka and Tamil Nadu. Dr. S. A. Tharmalingam and Kovai Mahesan, the president and secretary of the Tamil Eelam Liberation Front (TELF), sent a telegram about the situation in Trincomalee to a number of embassies in Colombo. The text of the telegram read:

Tamils experience pathetic situation in Trincomalee. Killing, looting, arson now taking place under the government-declared curfew. Racist security forces behind violence. We seek immediate intervention of friendly nations to stop genocide of the Tamils.

Trincomalee

TELF also called for a hartal in Jaffna to protest against the violence in Trincomalee. It provided an opportunity for the Tamils whose blood was boiling when they heard of the atrocities committed by the security forces and the government against their brethren in Trincomalee. The hartal was total. All the shops were closed. Vehicles kept off the roads. So did the people. Jaffna wore a desolate look. The police and the army were furious. The government was frothing. Jayewardene gave the only answer he knew. On 2 July Suthanthiran and Saturday Review were sealed. Dr. Tharmalingam and Kovai Makesan were detained. The Competent Authority, Douglas Liyanage, justified the government action pointing out the destruction of state property on the day hartal was observed.

The TELF was not responsible for the violent acts committed that day. That was the work of the Tamil Eelam Liberation Army, a break-away group of TELO. It was led by Oberoi Thevan. The TELA burnt buses, attacked post offices and other government buildings. The TELA also bombed and burnt the Yal Devi express train which plied between Colombo and Jaffna during the daytime.

The situation in Trincomalle was getting worse daily. Amirthalingam visited the city on 1 July to make an assessment of the conditions there. He returned to Colombo the next day and sent Jayewardene the following telegram:

Just returned after personally studying situation Trincomalee. Reports of violence by both sides absolutely incorrect. Over sixteen people killed – all Tamils. About forty people in hospital seriously injured by cutting and shooting – over thirty-five Tamils. One hundred and fifty houses burnt – over ninety five percent Tamil houses. Nearly a thousand people dehoused and in refugee camps – not one Sinhalese. Services conduct search in Tamil areas terrorizing people and this followed immediately by thugs attacking the Tamil people and setting fire to the houses. In spite of heavy loses of life and property for Tamils very few Sinhalese offenders arrested and remanded. About eighty percent in custody Tamils. Sinhalese offender arrested in the act or immediately thereafter released. Police and service personnel definitely partisan. Tamils can defend themselves if the forces are withdrawn. Forces preventing self-defence by Tamils nd providing opportunity for attack by hoodlums. Tamil officers sent to Trincomalee totally inadequate. Please send sufficient senior Tamil officers and lower ranks to inspire confidence among Tamils. Please stop massacre innocent Tamils in their own homeland by Sinhala hoodlums with connivance of Sinhala forces.

Amirthalingam followed up the telegram with a letter on 5 July. In it he said, though the scale of violence had diminished, the tension and sporadic incidents continued. “Even last night a Tamil person by the name of Suntharan was cut and killed by Sinhala hoodlums.” He added that the Tamil people were living in fear.

In that letter he also told the president an incident to illustrate the extent to which communal hatred had permeated the armed forces. He said:

The role of the armed forces in the recent incidents in Trincomalee leaves much to be desired.The incident when a Tamil naval personnel was assaulted by his colleagues for taking strong action at Abeyapura junction when two Tamils were killed and several severely wounded shows the extent to which the communal hatred had permeated the forces.

Police, armed forces and the Sinhala public had been infected by the virus of anti- Tamil violence. No wonder. They got their virus from their leaders.

Nancy Murray, a member of the Campaign Against Racism and Fascism and the Council of the Institute of Race Relations, commented about the situation in Trincomalee in her work Sri Lanka: Racism and the Authoritarian State. The relevant paragraph which appeared in the chapter “The State Against the Tamils,” page 104 reads::

“The two-months pogrom at Trincomalee left the town in ruins, thousands homeless and over 30 dead by the end of July. There was a certain method in all this destruction. For years, the government had been sponsoring Sinhalese settlement of Eastern Districts, determined that the Sinhalese, and not the Tamils benefit from the Mahaweli Development Scheme. By 1983, some of the Eastern Districts were becoming predominantly Sinhalese. These settlers were too willing to take part in acts of aggression against their Tamil neighbors, as part of their expansionist drive. The government also hoped that the Sinhalese settlers could be duped into accepting an American military presence in their midst – on the grounds that what the Tamils saw as bad must be viewed as good by the Sinhalese.”

Next: Chapter 36: ‘We are going to break heads’

To be published April 7