Of 1987

by Sachi Sri Kantha, May 29, 2022

This is a sequel to my previously posted item of March 11, 2022, ‘On Rajiv Gandhi’s pretense for Eelam Cause: ‘Operation Flower Garland’ of 1987.

I provide a 1987 anthology below, consisting of

- editorials that appeared in the New York Times (June 7, 1987) and the Asiaweek (Hongkong, June 14, 1987)

- 12 published letters from the readers of the Asiaweek.

- Journalist Mervyn de Silva’s erudite commentary in Far Eastern Economic Review.

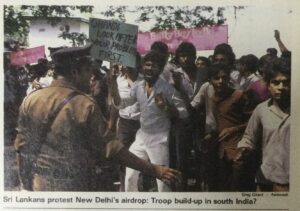

Sinhalese protest New Delhi’s airdrop [Asiaweek, June 28, 1987] Poster: ‘Ghandi look after your problems first’

One caveat: Materials (editorials, letters and the commentary) presented here are sprinkled with ethnic, linguistic and ‘foreign’ biases. For example, Mervyn de Silva concluded his erudite commentary with a thought, that Gandhi’s 1987 airdrop “was also a message to the Tigers that they are not the ultimate protectors of the Tamil people.” Later events proved that this was indeed a misinformed inference. Rajiv Gandhi died in 1991. For the next 18 years, Tigers [LTTE that is] did assume the mantle of ultimate protectors of Eelam Tamils, despite facing nefarious deeds by alphabet soup of gumshoes (India’s RAW, CBI, DIA; Pakistan’s ISI; Uncle Sam’s CIA; Israel’s MoSSAD) towards their goal of Eelam. After the passage of 35 years, we should reflect, which of these contributions are nearer to the truth, despite their inherent biases.

Mr. Gandhi, on Four Fronts

[Editorial, New York Times, June 7, 1987]

India calls it ‘humanitarian aid’ to beleaguered Tamil threatened with massacre. Sri Lanka vehemently denies atrocity charges and denounces India’s air drop of supplies as ‘a naked violation of our independence.’ India’s Rajiv Gandhi has become as much field marshal as Prime Minister, while armies mass on all the subcontinent’s fault lines. It’s past time for him to stop all the marching and to restart negotiations on four fronts.

Chinese and Indian troops are reportedly reviving a boundary dispute that in 1962 led to a war. Mr. Gandhi is staging nonstop military maneuvers on the India-Pakistan border, in anger over Islamabad’s nuclear ambitions and its U.S.-aided arms buildup. And within India, the Punjab is again torn by violence between Sikhs and Hindus, while Hindus and Moslems step up violence against each other in the northern state of Uttar Pradesh.

Such internal violence is an old Indian problem; the frontier maneuvers are most probably shadow boxing; and Mr. Gandhi’s resort to big-stick diplomacy in Sri Lanka recalls Indira Gandhi’s belligerence with smaller neighbors. Mr. Gandhi begins to look like his testy and authoritarian mother, but without her cunning.

It is everyone’s interest to stop the killing in Sri Lanka, resume negotiations and prevent two ethnic communities from embroiling the world in their civil war. Dismayingly, India has plunged into intervention before independent monitors established what happened in Sri Lankan sweeps against Tamil insurgents on the northern Jaffna peninsula. There’s more than a suspicion that Mr. Gandhi wanted the headlines, not the evidence, in first ordering a flotilla to carry aid to rebels, then mounting an airlift when Sri Lankan dared to block the relief boats.

Standing tall for two million Hindu Tamils against Sri Lanka’s Buddhist Sinhalese helps Mr. Gandhi at home – especially heading into Thursday’s critical election in the northern state of Haryana. The ruling Congress Party has lost a string of local elections, and badly needs a victory.

Mr. Gandhi can truthfully say that he tried to mediate, and that twice Sri Lanka’s president, J. R. Jayewardene, withdrew concessions under pressure from hard liners. But this ignores atrocities committed by Tamil terrorists, New Delhi’s inability to clamp down on their training camps and to prevent the arms flow across a narrow strait. And in December, Mr. Jayewardene came up with an autonomy compromise. Mr. Gandhi liked it, but Tamil militants rejected it furiously.

Mr. Gandhi did not light these fires but he is now fanning them. Where is the calm, good humored and conciliatory Rajiv Gandhi who so impressed the world a year ago?

*****

War without End

[editorial, Asiaweek-Hongkong, June 14, 1987, pp. 13-14]

As this was being written, an Indian flotilla of nineteen fishing boats was chugging across the Palk Strait bearing relief supplies for Sri Lanka, which was not noticeably happy about getting relieved. The Sri Lankan military was in the process of mounting a concerted drive to rewin Jaffna peninsula from Tamil guerrillas who have enjoyed free run of the island’s sandy northern spur for the past two years. Halting a siege to give the foe the opportunity to reload his larders and guns is not a principle of warfare figuring prominently in Clausewitz. But then, nearly everything about Sri Lanka’s sputtering fourteen year old civil war seems to have been dictated by contingency and haphazardness. With the ability to enforce its writ hedged rounded by formidable constraints, the majority Sinhalese government in Colombo has had to settle for impromptu displays of ‘doing something’ – the velvet glove one month, the iron fist the next. In such an atmosphere India’s ‘mercy mission’, complete with press boat and half-hourly progress reports, simply gave the theatre of appearances a cinematic flourish.

Unfortunately, the fact that confrontation at sea avoided fireworks looked to be anything but a happy ending to the showdown in Jaffna. With this cheeky but essentially peaceful bit of melodrama, Mr. Rajiv Gandhi had clearly hoped to satisfy Indian clamouring for intervention in the siege. Evidently few of New Delhi’s own improvisationists had thought out what would happen if the flotilla was turned back, as it was. This now threatens only to heighten indignation within India and intensify calls for forceful measures. That likelihood threatened in turn to upgrade Sri Lanka’s intractable crisis into full-dress anarchy.

Since he came into the prime ministership, Mr. Gandhi has led India in pursuing an unfamiliarly responsible and level-headed policy towards his neighbour’s communal strife. He has upheld Colombo’s sovereignty, offered and exercised New Delhi’s services as a mediator, and dragged Tamil guerillas to the peace table by calling in the debts they owe their sanctuary-giver. In fact, New Delhi’s fine-tuned approach to the conflict, though often more timid than it should be, has been the one bright spot in an otherwise muddled regional policy. Now all the careful diplomacy stands to go up in smoke overnight. In domestic straits himself, Mr. Gandhi is less able to resist a quick, crowd-pleasing answer. Even short of invasion, heavier logistical support and moral championship of the guerilla cause would be enough to keep Colombo’s hold on the Tamil-dominated northeast untenable. President Jayewardene has invested enormous political capital in his determination to restore peace soon through negotiations if possible, militarily if necessary. If he can do it neither way, any number of Sinhalese chauvinists and crackpots are poised to grab for the wheel and steer Sri Lanka down the road to Beirut.

But arguments like this may be only a waste of breath anyway. Feelings are so high, wounds so deep, as to push the crisis all but irretrievably beyond reason. With 5,000 deaths and counting, Sri Lankans of every kind have enough outrages seared in their memory and so many scores to settle that reconcilement, if it ever comes, may have to wait for the passing of today’s living generation. Weary observers might fairly conclude that the only answer is partition. As recent circumstances have proved, however, the independent state of ‘Eelam’ which the Tamil Tigers and affiliated goons have been fighting to their civilian countrymen’s deaths for would be far short of lotus land. If anything, it would be South Asia’s premier basket-case. The economic quarantine of Jaffna thrown up by Colombo in January, when the Tigers undertook to set up their own administration, underscored how completely dependent the arid north is on the south for food, fuel, electricity, the works. Eelam would have to live off Indian hand-outs, and across the water India’s Tamil Nadu state, whose government has been so bravely supportive of the thugs, would be dismayed to find more refugees from the peace than from the war.

For their own part, meanwhile, the Sinhalese majority’s promising start at achieving their own economic miracle would certainly be worse off without the bureaucratic and commercial skills of Tamils. Ca anything be done? The first thing has to be uniting mainstream Sinhalese parties behind Mr. Jayewardene’s peace formula, which equitably proposes to devolve a great deal of autonomy to the Tamil regions (other regions, too). If that is impossible – if opportunists like Mrs. Sirimavo Bandaranaike cannot grasp the urgency of the moment – then any settlement will remain vulnerable to the next change of government. If reason still has a constituency, however, the next thing would be for Mr. Jayewardene to get his priorities straight. One cannot contain an insurgency with half-hearted measures. Some development projects would have to be sacrificed to spending for a proper military, properly run. That means hardware less than well-organised, disciplined troops trained in not only how to shoot but, more important, when not to shoot. [note by Sachi: italics as in the original.] The army in the field has proved a loose cannon, doing the cause of unity more harm than good.

No military action is likely to win the war, though, without aggressive promotion of the peace terms. Experience has shown, on the other hand, that even India, though it might lead Tigers to a table, can’t make them eat. Given this clear intransigence, the only thing to do is isolate the guerillas – socially, psychologically – by weaning fellow Tamils’ support away. And the best method of doing that is by offering a better alternative: arbitrarily naming provisional provincial governments of moderate Tamil leaders like the formerly reviled Mr. Amirthalingam, now in exile. Marxist forces always self-destruct, but alienation quickens when the disaffected have a more promising leader to rally behind. Increasingly, Tamils should be given peacekeeping duties, and above all, India must get squarely behind this leadership. Failing all this, India will have a kind of hegemony with a vengeance. It can then keep up supply boats without end, minister to inflows of the wounded and hungry without respite, look on and enjoy its Indian Ocean Zone of Peace.

*****

War in Sri Lanka

[Letter; Asiaweek, June 28, 1987, p. 7]

Some time ago you asked then Foreign Secretary A.P. Venkateswaran to state India’s goals in the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation and explain how members’ fears of Indian dominance could be assuaged [Viewpoints, Sept. 28]. Part of his reply was as follows: ‘SAARC is based on the principles of mutual benefit, sovereign equality, territorial integrity, political independence and non-inteference in the internal affairs of other states. So we don’t see any question of a member country trying to dominate others, or the need to assuage such fears.’

India’s ‘relief’ airdrop violated Sri Lanka’s airspace and every other principle that SAARC stood for. Accordingly, Sri Lanka should pull out of SAARC, and uphold its integrity as a small but proud nation. – U.A.S. Jindasa, Kuala Lumpur.

*****

Thugs, You say?

[3 letters with a tagged Editor’s note; Asiaweek, July 5, 1987]

In ‘War Without End’ [Editorial, June 14], you try to portray President Jayewardene as a man of principled reason and the Tamil rebels as thugs. Gentlemen, have you visited the Jaffna peninsula?

My family lives there. Few weeks ago I received a letter from my sister. She wrote that one of my high-school friends, Dr. Kathamuthu Visvaranjan of Jaffna General Hospital, had been killed near Palaly Army Base. He’d been asked to identify himself and while he was doing just that he was shot by a Sinhalese soldier standing right behind him.

My friend was in his mid-thirties and had a child. Do you expect the child will grow up a friend of the Sinhalese army? For ten years there have been thousands of Tamil kids in Sri Lanka’s Northern and Eastern regions growing up without fatherly love. The government’s actions are breeding a new generation of rebels. – Sachi Sri Kantha, Tokyo, Japan.

You’ve written a balanced assessment of the situation only to betray your analysis by using the word ‘thugs’. The Jaffna Tamils are a cultured and disciplined lot with a passion for education, culture and good-neighbourliness. They fought several battles for and on behalf of the Sinhalese over several centuries. They were in the forefront of the emancipation of the Sri Lankan community (Sinhala-speaking and Tamil-speaking) from British bondage in ’48. Labelling them ‘thugs’ is unbecoming of Asiaweek. – ‘A Patriotic Sri Lankan’, Colombo.

Are the PLO and the MNLF ‘thugs’ too, then? – A Navaratnam, Klang, Selangor, Malaysia.

The only thugs referred to were the ones the Tamil Nadu government ‘has been so bravely supportive of.’ – ED(itor).

*****

The Parippu Invasion

[3 letters; Asiaweek, July 12, 1987]

Across the water from an independent Eelam, you say, ‘Tamil Nadu state, whose government has been so bravely supportive of the thugs, would be dismayed to find more refugees from the peace than from the war [Editorial, June 14]. In my opinion, Tamil Nadu is the last place the people of Jaffna and thereabouts will want to go if Sri Lanka’s sovereignty is trampled upon in the name of some ‘independent’ state.

In such a situation the great majority of Tamil refugees would, I assure you, head for Sri Lanka. Why? Because they have always known what you now state, namely that they are not wanted in Madras or thereabouts. And because contrary to the image that has been put out by certain foreign publications, the Sinhalese have a very strong tradition of generosity, tolerance and sharing when it comes to refugees.

It is of course true that without this tradition the country would have been spared the trauma of insurrection. On the other hand, it is a tradition that ultimately will save our ountry. – C.M. De Silva, Colombo.

If Mr. Rajiv Gandhi was sincere in his efforts to bring a quick settlement of the Sinhalese-Tamil problem in Sri Lanka, he could have ordered the closure of the Tamil guerilla bases in south India. When the Sri Lankan government came up with a deal acceptable to the Indian government, he could have forced the guerilla leaders to negotiate.

But Rajiv is an impotent, unable to act against the wishes of that patron of guerillas Mr. M.G. Ramachandran, the chief minister of Tamil Nadu, who has a vested interest in this matter. So he chose to boost his own sagging ego by humiliating a defenceless neighbour. I hope he will not invade Fiji with humanitarian aid! – Terrence Almeida, Boroko, Papua New Guinea.

Assuming all the packages were retrieved, which they weren’t, and assuming the ‘aid’ was distributed evenly among the Jaffna population, which it wasn’t, what the Indians described as ‘urgently needed relief supplies’ and ‘certainly not a symbolic gesture’ (according to Dr. M.L. Gupta of the Indian Red Cross) amounted to less than 200 grams of food per person.

For this, Rajiv spent vast sums to mobilise a flotilla of boats, a flight of military transports and an escort of fighter planes.

Seven ounces! ‘Urgently needed relief supplies’? ‘Certainly not a symbolic gesture’? It is a strange fact that whenever Rajiv has problems at home, we start hearing about a nuclear threat from Pakistan, a troop buildup on the Chinese frontier, border-crossings from Bangladesh, or Sri Lanka’s ‘anti-Indian’ friends. Like mother, like son.

For Rajiv, the Sikh call for Khalistan is terrorism whereas the assault on the Golden Temple was for the sake of the country. He calls for extradition treaties with other countries in connection with Punjab, but, through his secret service, RAW, protects Sri Lankan terrorists on Indian soil. They are allowed to carry arms and ammunition openly in Tamil Nadu.

The strangest and most unfortunate fact is that no country or organization has come up with an effective response to this naked infringement of one country’s sovereignty by another. Where is the Non-Aligned Movement, which India helped to start? Where was SAARC, the regional watchdog? Where was the International Red Cross? Where was the UN? Where were the countries that stand for freedom, democracy, independence and sovereignty? – Rudolph Perera, Nugegoda.

*****

Intervention in Sri Lanka

[3 Letters; Asiaweek, July 19, 1987, p. 7]

Many Indian and other non-Sri Lankan journalists were aboard the Indian Air Force transport planes that dropped supplies illegally over northern Sri Lanka on June 5. I strongly believe this kind of behavior fails to meet journalistic standards of honest conduct.

I’d like to remind the journalists who participated in India’s illegal airdrop that they are not exempt from every person’s duty to respect a sovereign nation’s territorial integrity.

–A.M. Mahboob, Winnipeg, Manitoba.

Your good reporting, especially in ‘Sri Lanka Options’ [International Affairs, June 28] will bring public awareness to Sri Lanka, where full knowledge of the tragic situation is limited by government censorship. But while I congratulate you, I must say I was disappointed that you chose not to publish any photographs showing the destruction and indiscriminate killings in the bombing by Sri Lankan government warplanes. – Nathan Sunder, Beverly Hills, California.

Re ‘Sri Lanka Options’: India’s politicians acted not out of love and compassion for the Tamils in Sri Lanka but because there are 50 million votes in Tamil Nadu. Rajiv Gandhi now obviously depends on an election bonanza in South India. It’s a pity that India, a leader of the Non-Aligned Movement, has resorted to training guerillas and giving sanctuary to those trying to carve out a communist state in Sri Lanka.

Now it is up to other interested parties to douse these passions by offering to act as sensible intermediaries. – ‘A Sri Lankan’, Darwin, Australia.

Reading ‘Battle for Jaffna’ [June 14] and ‘Frontline Jaffna [June 21], I see the editors of Asiaweek are blind to the fact that on June 4 a timely headline in Delhi might have read ‘Swedish audit confirms Bofors paid $40 million!. When even Asiaweek missed the turn, Mr. Clean had his way on what should and should not capture public attention next day. – G.K. Seneviratne, Colombo.

*****

That Word Again

[Letter; Asiaweek, July 26, 1987]

I was very very happy to see the remarks by Dr. Sachi Sri Kantha of the University of Tokyo [Letters, July 5]. He complains that in a commentary published in your June 14 issue you ‘try to portray President Jayewardene as a man of principled reason and the Tamil rebels as thugs.’

Dr. Sri Kantha, please consider the following and suggest an appropriate word to distinguish people who support such activities.

All of Sri Lanka’s Tamil speaking engineers and doctors, and more than 90% of the island’s Tamil-speaking scientists – including Dr. Sachi Sri Kantha – received their first degrees from universities located in the areas where Sinhalese live. However, not a single student with Sinhala as his or her mother tongue was permitted to receive a degree from Jaffna University. All the Sinhalese living in Jaffna, including those who went to study at Jaffna University, were either killed, robbed or chased out of the area.

More than 80% of the Tamil people in Sri Lanka didn’t live in Jaffna. They lived in harmony with the people in the rest of the island. But no Sinhalese or Muslims were allowed to do business or move freely in Jaffna.

People in Jaffna discriminated against Tamils living in plantation areas and against low-caste Tamils. Villagers living in various parts of the country were robbed or threatened, public institutes destroyed.

The most suitable place for a Tamil homeland is Tamil Nadu, where more than 50 million Tamils live. In the 1950s and ‘60s, some people wanted to separate Tamil Nadu from India. The idea went nowhere then, but in considering the present Indian Prime Minister’s ‘immediate relief supplies’ of 200 grams of food per person in last month’s Jaffna airdrop, I have to wonder whether Mr. Gandhi would not support such a proposal. – Jayantha Herath, Tokyo.

*****

The Jaffna View

[Letter; Asiaweek, Aug. 9, 1987]

I don’t blame my fellow Sri Lankan Jayantha Herath [Letters, July 26] for the tone of his response to me. The fault lies with racist politicians. Discrimination along caste lines is not a custom restricted to Jaffna Tamils; for 40 years it caused havoc in the selection of Sri Lankan prime ministers. Why couldn’t C.P. de Silva become premier after the assassination of S.W.R.D. Bandaranaike by a Buddhist priest in 1959? Some say it’s difficult for Prime Minister Premadasa to aspire to the presidency: he wasn’t born in the Sinhala Goigama caste which from 1947 to 1977 kept two feudal families – the Senanayakes and the Bandaranaikes – in power. Sri Lankans with Portuguese or Christian surnames (Perera, de Silva, Fernando, Matthews, etc.) have only a remote chance of reaching the ‘throne’.

Mr. Herath should see the skeletons in the cupboards of Sinhalese society before casting stones at the Jaffna Tamils. – Sachi Sri Kantha, Tokyo.

*****

Ethnic Conflicts Respect No National Boundaries

Mervyn de Silva [Far Eastern Economic Review, July 30, 1987, pp.20-22]

In 1986, the UN Year of Peace, there were 36 wars or armed conflicts which claimed 3-5 million lives and involved 40 nations including superpowers. Considering its small population of 15 million, the Sri Lankan conflict, undeniably indigenous in origin, has made more than a modest contribution to this death toll. The insensate and unabatingviolence makes the island’s tragedy no less harrowing than Lebanon’s.

Like most Third World conflicts, the Sri Lankan crisis – apart from its ethnic origin – has regional and international implications and, more important, is rooted in the erosion of democratic processes in the country. In the initial decades after independence in 1948, Ceylon – now Sri Lanka – enjoyed a reputation as an exemplary ‘new’ nation because of its robust democracy and equitable economic policies. But the four-year old Tamil insurgency has now dragged the country’s polity, not just its regime, to a dangerous precipice.

However flawed in some aspects, the 30-year post-independence achievement, particularly the recognition of minority rights, was based on a consensual model in political, economic and foreign policies. In 1978, and more clearly, in late 1982, there was a conscious rupture with this past.

In the July 1977 general election, the rightwing United National Party (UNP) secured less than 52% of the popular vote but bagged 85% of the parliamentary seats, a quirk of the ‘first-past-the-post’ electoral system. The Sri Lanka Freedom Party (SLFP) – the UNP’s main rival – managed only eight seats, though it secured about 30% to the total votes. The Tamil United Liberation Front (TULF) swept the polls in the predominantly Tamil northern region, making its secretary-general the leader of the opposition in parliament, an unprecedented development that was to herald the coming ethnic confrontation.

By early 1978, the UNP abandoned the well-tested Westminster model and installed a powerful executive presidency. The rationale for this change was ‘stability’, the prerequisite for accelerated growth through a free-market economy, dependent on foreign investment and aid. In 1980, SLFP leader and former prime minister, Sirima Bandaranaike, was expelled from parliament for ‘abuses of power’ while in office.

The critical turning point came in December 1982 when a device all too familiar in authoritarian states, but unknown in Sri Lanka, was used. In place of the general election due shortly, a referendum was held, under emergency rule. The referendum – carried with a bare majority – extended parliament’s term and the ruling UNP’s overwhelming dominance in it, by another six years.

The relatively open political system was firmly closed. For the Tamil leadership, it was the end of the road. Since 1956, when Sinhalese became the sole official language the Tamil leaders and their Gandhian ‘passive resistance’ campaigns had failed to check a process which the Tamils now describe as majority domination and discrimination.

For the younger generation, a university admissions scheme – introduced in 1973 and favouring the Sinhalese – was a deadlier blow than the official language policy. [Note by Sachi: The year was 1971, and not 1973, as stated by de Silva. I should know, because I entered the university in 1972 from Colombo, and was in the 2nd batch of Tamil students, affected by this racist policy. This policy’s father was the then Minister of Education, Alhaj Badiuddin Mahmud (1904-1997), an appointed Muslim member to the parliament, and a founder member of the SLFP.] In the arid north, higher education and the public service were the only road to gainful employment. In the eyes of the Tamil youth, the TULF had outlived its usefulness. So the torch was passed on to the youth and a generational revolt startled among the Tamils. The weapon of parliamentary protest was replaced by a resort to arms. Failing to read the signs correctly, Colombo adopted an even tougher law-and-order approach. Terrorism acquired a popular base.

An epochal ethnic resurgence in new nation states has put to the severest test the primary loyalty of communities within those states, especially national minorities with a distinctive culture. In this particular stage of state formation, that allegiance seems to lie more often with ‘nation’ than with ‘state’. A Kurd is a Kurd whether he has been born in Iran, Iraq or Turkey.

Ethnic loyalty transcends borders. Thus, ethnic unrest not only brings turmoil to society and danger to the state but complicates inter-state relations. And since the state is the basic unit of the world system, the current ethnic challenge is the most anti-systemic force today.

The ethnic situation in Sri Lanka had always a built-in external factor created by geography, history and culture. Most Tamils in Sri Lanka – 13% of the island’s population – identify culturally with their 50 million ethnic brethren in the south Indian state of Tamil Nadu. The Palk Strait separating Sri Lanka from southern India has traditionally been a haven for smugglers, refugees and rebels.

The vicious anti-Tamil riots of July 1983 activated this long-dormant factor. The Tamils had voted overwhelmingly against the referendum seven months earlier, the last gasp of democratic protest. Rebel activity increased.

More than 100,000 refugees fled to Tamil Nadu, already an operations base and propaganda centre of young Tamil militants. When a panic-stricken regime moved yet another constitutional amendment to force MPs to renounce separatism, the TULF withdrew from parliament and all its leaders sought exile in Madras. Symbolically, the Sri Lankan Tamil had found shelter in the greater Tamil homeland.

In any event, the TULF had slowly awakened to the truth that its demand for regional autonomy, via devolution and decentralization, would not be granted. It could not be. Devolution is the antithesis of centralization. A authoritarian regime, which refuses to share power with the non-violent Sinhalese opposition, could hardly share power with a minority, whose youth had pointed a gun at its head.

The aftermath of the July 1983 riots gave then Indian prime minister Indira Gandhi the chance to offer her good offices. A UNP regime rattled by the international consequences of the riots, especially to its aid-dependent economy, readily accepted the offer. The balance of political forces in Sri Lanka did not permit an internal settlement of an essentially internal problem. Equilibrium could only be restored by a superior external force.

Mrs. Gandhi seized the day with all ill-concealed pleasure. Sri Lanka had been India’s friendly neighbour, and therefore highly valued. Pre-independence Sri Lankan leaders drew ideas and inspiration from the Indian nationalist movement. Far more significantly, Sri Lanka, like India, was a secular democracy, followed middle-path economic policies, and was stoutly non-aligned. All that changed with the 1977 polls in Sri Lanka.

The UNP’s economic model was Singapore and South Korea. That non-alignment – a highly flexible policy, anyway – would be reshaped to suit this model was made embarrassingly plain when Colombo was sufficiently disingenuous to apply to join ASEAN. The glamour of the ‘Singapore Girl’ tantalized an elite that had been imprisoned too long in an austere and closed economy.

For good reasons, Mrs Gandhi watched these Sri Lankan policy changes with rising anxiety. After the British leased the island of Diego Garcia to the US, the latter’s military presence in the Indian Ocean increased, causing concern to New Delhi. Thus, She encouraged and strongly supported Bandaranaike’s UN resolution in the 1970s to declare the Indian Ocean a zone of peace. Indian anxieties turned into an obsessive concern as the US created its Central Command in the early 1980s to counter Soviet activities in the Gulf and the Indian Ocean.

Colombo’s negotiations with an American firm, which has been a Pentagon contractor, to build oil-storage facilities in the strategic Trincomalee harbor riled Mrs Gandhi. An Indian offer was rejected outright. So was a Soviet feeler. However, both countries were more disturbed by an agreement with the US for a transmission facility for Voice of America in Sri Lanka, which it was alleged would also have a military dimension.

New Delhi’s security anxieties are interactive, external and domestic. Swept by sectarian strife, the Indian elite has a paranoid fear of Balkanisation, as ethnic and regional nationalisms challenge the centre through armed struggle in many states. Recent history has also made India hyper-suspicious of US aims. During the Cold War, Washington viewed India’s non-alignment as immoral. Besides, the US took Pakistan’s side on Kashmir, the generic conflict in the Subcontient. Since then, the Indian elite is convinced that the US is determined to vest Pakistan with a status of parity, denying India its regional pre-eminence.

Sri Lankan intelligence agencies now know that Mrs Gandhi began to take an interest in the growing Tamil revolt only in late 1982. In 1980, she had described Bandaranaike’s expulsion from parliament as ‘an outrage’ and a ‘disgrace’. The presidential polls and the referendum foreclosed her hopeful option of a change of regime in Colombo and a less hostile foreign policy.

After July 1983, the Tamil refugee presence in Madras may have become a social irritant. The Sri Lankan issue had, however, entered the bloodstream of Tamil Nadu politics. The state’s chief minister, M.G. Ramachandran was soon the personal patron of the largest guerilla group, the Tamil ‘Tigers’. True, Rajiv Gandhi rode to power at the end of 1984 on the crest of an emotional wave after his mother’s assassination. Yet, his Congress Party had little influence in the south. In Tamil Nadu, the Congress was a junior partner of Ramachandran.

“We will be judged by our relations with our neighbours’, said the buoyant young Gandhi, full of high ideals. Reconciliation with neighbours meant political compromises with restive and rebellious minorities at home. So Gandhi followed up with political accords in Punjab, Assam and Mizoram. However, the Punjab accord has not eliminated Sikh extremist violence and India persists in accusing Pakistan of fomenting trouble.

It is not certain whether Mrs Gandhi consciously chose to make the Tamil rebels the cutting edge of New Delhi’s Sri Lanka policy. Anyway, her son inherited the problem. His more than two year old effort as honest broker has been a dismal failure. He has been unable to tame the intransigent Tigers. He has watched Colombo undertake a massive military build up, receiving equipment, training and advice from foreign sources.

In a contradiction that is a dialectician’s delight, Colombo’s supporters – Pakistan, Israel and China – were bound to infuriate the honest broker and fit all too neatly into his instinctive response to the host of problems that suddenly confronted him.

Gandhi was under siege: humbling electoral defeats, governmental and party crisis, and scandals which did not leave him unscathed. And Punjab continued to explode as Hindu-Moslim riots went on unabated. Skirmishes on the Chinese border had followed the tense Indo-Pakistani confrontation early this year. The US had given massive military aid to Pakistan. By May, Gandhi was holding countrywide rallies invoking the themes ‘destabilisation’ and the presence of the ‘foreign hand’, the favourite rallying cries of his mother.

Systems analysis tells us that assertive actions externally and other morale-boosting diversions can help contain domestic disequilibrium. That is precisely what President Junius Jayewardene did when he mounted a massive military offensive in the north when Sinhalese opinion in the south was boiling after the Good Friday massacre in the northeast and the terrorist bombings in the heart of Colombo.

Gandhi’s reply converted the mediator into the interventionist. The airdrop of relief supplies over Sri Lanka’s Jaffna peninsula in early June, though humanitarian in intent and harmless physically, was a violation of a small neighbour’s sovereignty. Whether he knows the vogue word or not, Gandhi had bowed to the ‘inter-mestic’ – those problems that lie at the inter-face of the international and the domestic.

The airdrop was a ‘help to the Tamils’ and a ‘message to Colombo’, explained Gandhi. He might have added that it was also a message to the Tigers that they are not the ultimate protectors of the Tamil people. He has also asserted India’s regional supremacy. Can he now deliver? Or will the region’s paramount power, like the superpowers, learn the awesome dilemmas and limits of power in a Third World crisis?

*****