Notes on the White Anglo Saxon Protestant (WASP) Editorials

by Sachi Sri Kantha, September 2023

Preamble and Inference

Though digital writing has many merits, one of its demerits (i.e., disappearance of past published records into the digital black hole, within few years) is a pain in the neck for me. Originally, I compiled this collection of White Anglo Saxon (WASP) editorials on Black July 1983, in 2004. However, in the Sangam site archives, I could not retrieve it. Luckily for me, the now defunct Tamil Nation site, then managed by Nadesan Satyendra, had a version that I could retrieve. Now, for the 40th anniversary of anti-Tamil riots of July 1983, I have re-assembled the material, with an up-dated Preamble and inference.

In July 1983, I was a graduate student at the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign. One of my regular haunts in that wonderful university was the Newspaper Library. Those were the pre-internet and even pre-computer days. To receive any information about events in Sri Lanka, I had only two sources; (1) the air-mail letters from my family members, and (2) newspapers published from various cities. Of course, there was a telephone link. But, for reasons of thrift, I hardly used the telephone to contact my family members, except in an emergency. Thus, as a matter of daily routine, I avidly checked the various newspapers which came to the Newspaper Library of the university, for Sri Lankan news. When I located any such news report, article-commentary, editorial or even ‘a letter to the editor’ of substantial information on Tamils and Sri Lanka, I made it a habit of photocopying them.

Since the infamous bibliocaust of Jaffna Public Library in June 1981, I had motivated myself to become a Tamil archivist. This is how I came to be in possession of the editorials which appeared in various newspapers following the July 1983 anti-Tamil riots. Re-reading the editorials penned by journalists – almost all, probably illiterates in Tamil language – produces conflicting emotions for me. But this is how those journalists drafted – albeit, the first draft of – the history of the pogrom. Before I left Ceylon in 1981, I had high regards for anything which appeared in English about Tamil affairs from the West as well as from India. I was under the false impression that these editors (being not Sinhalese) were more intelligent in understanding Tamil affairs. After July 1983, I had to revise my impressions about the literacy of the editors who man Western news media. They may be less biased and less racist than the majority of the Sinhalese editors, but quite a percentage of them are cursed by sheer ignorance. If these guys are so erratic on events and issues I know about first hand, then how can I rely on their wisdom for their reports on locations and cultures which I’m hardly familiar with?

One cannot gain anything by just cursing the journalist rascals who are ignorant about the Tamil issue in Sri Lanka. The old adage says, ‘It’s better to light a candle than curse the darkness’. Thus the July 1983 anti-Tamil riots more or less forced me to write about Tamil issues, which I’m familiar with in English. Thereby, at least I could counter the errors of facts and interpretation, as well as educate a segment of readers who are interested in learning something about the exploding Tamil issue in Sri Lanka.

Below I present a sample of ten editorials which appeared during July-August 1983, in the leading newspapers and magazines of the WASP [standing for, White Anglo Saxon Protestant] world; four from London, two from Toronto, two from Washington DC, one each from Boston and Montreal.

The Times (London), July 29, 1983

Montreal Gazette, July 30, 1983

Economist (London), July 30, 1983 and Aug 6, 1983

Boston Globe, Aug 1, 1983

Globe and Mail (Toronto), Aug 1, 1983, Aug 8, 1983

Washington Times, Aug 3, 1983

Washington Post, Aug 5, 1983,

The Observer (London), Aug 7, 1983

I have excluded the Indian publications in this sample.

‘MacArthur erection’ errors and skin deep sympathy

What one finds in the following collection of editorials can be summed up as follows: (1) an impulse to sermonize, (2) blame shifting on Eelam Tamils, (3) absurd geographical comparisons, (4) amnesia on Ceylon’s colonial history, especially how the British contributed to the current mess by their imperial impulse to loot and artificially patch-up two nations into a politically non-viable state, and (5) factual howlers of notable proportions. Though the presumed intent of almost all the editorials were honorable, their impact was nonetheless horrendous, because of the above listed errors. I have coined an eponymous phrase for such errors – ‘MacArthur erection’ errors – based on a true anecdote.

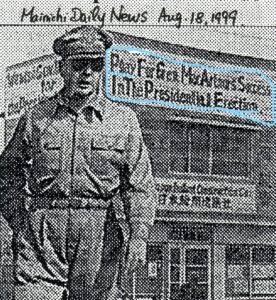

Gen McArthur’s success in erection 1952

General Douglas MacArthur (1880-1964) was the Lord of post-war Japan for nearly six years from late 1945. When the news came to Japan that the American General was about to test his popularity in the 1952 Presidential election primaries, the Japanese were ebullient in expressing their support for the General. In a prominent Tokyo location, a banner in support of Gen..MacArthur was prominently placed. It read, ‘[We] Play for Gen. MacArthur’s Success in the Presidential erection’. [this visual is presented nearby, reproduced from the Mainichi Daily News, Tokyo, Aug 18, 1999.] The embarrassing banner was due to the mix-up of alphabets L and R in two words. The correct version should have been ‘We pray for MacArthur’s election’. [In Japanese language, there is no equivalent of alphabet L; thus, alphabet R is usually substituted for L.]

It is my inference that almost all the ten editorials in this anthology were riddled with the Ceylonese version of ‘MacArthur erection’ errors. Sad to say, these commentaries also had an air of condescension and the bloated snobbery below the skin-deep sympathy for the victimised Eelam Tamils. Of course, the WASP editors had knuckle-whupped the then President J.R.Jayewardene for mishandling the tragic situation and for not exhibiting established norms of political leadership. This was based on the honorable assumption that Jayewardene was a statesman. But Eelam Tamils had known since the mid 1950s [as per his demonstrated opposition to the Bandaranaike-Chelvanayakam Pact] that one couldn’t expect anything better or anything of worth from that old fox. In July 1983, he did show ‘faultless leadership’ for what his constituency expected of him as an elected Sinhalese politician.

Now, after 40 years, only one of the ten editorials [that appeared in the Economist, Aug 6, 1983, under the caption ‘Not just the Tamils’] stands apart from the rest for its clarity of thoughts and time-withstanding precision. The editorialist presented four pragmatic options to solve the dilemma faced by the Sinhalese and Tamils in Sri Lanka. These were, (1) absorption – the wholesale merging of lesser ethnics with greater ones, (2) centralised despotism, (3) federalism, and (4) partition.

The current scene for Eelam Tamils

Of the four options put forward by the Economist editorialist, as I view the scene, only first two options are in operation concurrently in contemporary Sri Lanka of 2023.

Centralised despotism of Colombo has remained as the political norm since 1983. Jayewardene was followed by Premadasa in 1989, who was succeeded abruptly by Wijetunga in 1993 and who passed the baton to Chandrika Kumaratunga in 1994, to be followed by Mahinda Rajapakse, Maithiripala Sirisena, Gotabhaya Rajapkse and now Ranil Wickremesinghe.

Absorption – i.e., the merging of Tamil ethnics into the Sinhala pot has been occurring in the fringes, and the Tamils living in the hill country are being encouraged covertly by the sustained propaganda – to follow the path of Chandrika Kumaratunga’s medieval era ancestors and the 18th-19th century arrivals from Chettinadu of Tamil Nadu.

Thanks to LTTE leader Pirabhakaran’s vision of establishing a legitimate Tamil army, a de facto partition became a reality in the island, between 2000 and May 2009, which wouldn’t have been dreamt of by Tamils in 1983.

Following the defeat of LTTE in 2009, now the power brokers of various strata (international, regional and local types) are engaged in the fourth option – a mirage of federalism. How long such a half-hearted measure will last is anybody’s guess.

Ten Editorials on July 1983 anti-Tamil riots which appeared in the WASP Press

Item 1: Colombo’s Crisis [The Times, London, July 29, 1983]

“The news from Sri Lanka this week has recalled the horrifying events leading up to the division of India thirty-six years ago. The Hindu-Muslim-Sikh massacres of that time are reflected in the bloodshed, arson, looting that has sent thousands of innocent Tamils running for safety wherever they can find it. They are, it must be emphasized, a minority community whose status as citizens of Sri Lanka should be unquestionable. Unhappily, ever since Sri Lanka became independent in 1948, the current of Sinhalese nationalism has turned with envious anger on this community that played a part in Sri Lanka’s political and professional life under British rule out of proportion to its numbers.

The most recent events have revealed a culpable bias on the part of the forces of order. Early reports of rioting in Colombo before censorship was imposed agreed that the police were slow to intervene. Reports of action by naval units in Trincomalee and some recent army actions have suggested that reprisals were their aim, more likely to stimulate than to pacify. Worse than this, evidence of official Sinhalese hostility to the Tamils has been the government’s failure to respond to the palpable tension aroused two months ago when municipal and parliamentary by-elections were held. The campaign was said to be more like civil war than an election. Since then violence has followed with action and reprisal until the incident last week when thirteen soldiers were killed in an ambush by Tamil terrorists. The government should have been better prepared than they seem to have been for what has happened all over the country during the past week.

Needless to say, if one looks back over the history of the last thirty-five years there is blame to be put on both sides in the struggle over the rights and status of the Tamil community. Only in the last few years have events brought on a crisis of which the outcome can only be tragic unless national sentiment can be pulled together to prevent it. On the one hand the Tamil United Liberation Front, now the main representative Tamil body, has been insistent in its demand for a separate Tamil state in the north of the island – Eelam – a demand which in the eyes of many Sinhalese has given new force to the long-standing conflict. To this has been added on the Tamil side the emergence of the terrorist youth group – Tamil Tigers – disappointed by the response to peaceful agitation. Already they have a record of murders of police, attacks on soldiers and an unyielding attitude of belligerence that has cowed some of the moderates in the Tamil parliamentary party.

This sharpening of the issue and of the line-up of forces has taken a different and unforeseen form in Sinhalese political life. In 1977 Mrs Bandaranaike’s Sri Lanka Freedom Party lost heavily in the election that returned the right-wing United National Party led by Mr J R Jayewardene. Since then the SLFP has been further torn by a family split. With other opposition parties fading into small pockets, the leading, because numerically strongest, opposition party has been TULF. Thus the UNP, always the home of the strongest anti-Tamil feeling has been the more uninhibitedly outspoken, thanks to its dominance in parliament. In October, under the terms of his own revision of the constitution, Mr Jayewardene stood for election as president and was handsomely returned. Two months later he called a referendum on his proposal to extend the life of the present parliament, and here again he collected his solid vote excepting only the total opposition of the Tamil electorate.

Unfortunately Mr Jayewardene’s national popularity by no means extends to his party. He was aware of this at last year’s election and he has since culled some of his less appealing supporters, but not enough to erase a strongly anti-Tamil flavour. The result is that the Tamil problem is not subject to sufficient opposition scrutiny in parliament. After last year’s riots Mr Jayewardene saw the danger he faced as a politically dominant but lone leader of an unpopular party faced by increasing Tamil violence and increasing anti-Tamil fury. He then said that if he could not be proud of his party it would be better for him to retire from the leadership and make way for those who believed, as he put it, that the burning of innocent people and property was a way to solve the problems that faced Sri Lanka’s multi-racial, multi-religious, multi-caste society. Can he now, aged 77, lead Sri Lanka away from the path of growing communal violence that threatens it? It is hard to see any other political leader who could.

Item 2: Sri Lanka’s Bloody Shame [Montreal Gazette, July 30, 1983]

Sri Lanka’s claim to being civilized is drowning in the blood of its Tamil minority that the Sinhalese majority slaughters and burns. New government measures outlawing even peaceful Tamil separatism make more violence likelier. Sinhalese soldiers, sailors and policemen have joined the arsonists and murderers. Tourists fleeing Sri Lanka number the Tamil victims in the thousands.

The troubles go back to the 19th century when the British imported Tamil workers to Sri Lanka – then the island of Ceylon – from adjacent southern India. The Tamils are Hindu. The Sinhalese are Buddhists. The Tamils, as minorities often do, put a great effort into education and carved enviable places for themselves in the economy and the ranks of the British administration.

When Sri Lanka became independent, after the Second World War, its envious Sinhalese majority, 72 percent, often turned on thriving Tamils, 20 percent. On one occasion, the Sinhalese police burned half the Tamil capital city of Jaffna. Such savagery gave birth to the Tamil United Liberation Front with 18 members in Sri Lanka’s 168-seat parliament. They advocate separation by democratic means. But the existence of the TULF only increased Sinhalese violence which finally turned young Tamils to terrorism.

To stem this, President Junius Jayewardene advocated some measure of autonomy for the Tamils. But the Sinhalese majority wouldn’t buy it. It preferred increasing repression, led by the forces of law and order, which Mr.Jayewardene now longer can control. If he ordered them to stop killing Tamils, his troops might replace him with the usual cold-eyed, slimy colonel who is, no doubt, lurking under some stone, plotting.

Persuadably to forestall a military take-over, Mr.Jayewardene has now outlawed all separatist movements and said that people who advocate division of the country would be stripped of their civil rights. Sri Lanka’s president has thus turned his back on his earlier willingness to give the Tamils some autonomy. And in so doing, he leaves them no choice but to become guerrillas. What else can they do when legitimate political action is denied them and they lose all their rights if they hold views the Sinhalese majority rejects? It is through such denial of civic rights that long-lasting, bloody guerrilla wars are made.

Item 3: Week of the tiger: Let President Jayewardene call in a tamer for Sri Lanka [Economist, London, July 30, 1983]

Sri Lanka is an island with free speech, free enterprise and a climate that lures judicious travellers. It also has a separatist movement which promotes its aims with violence. Any acquaintance of Sri Lanka previously unaware of the Tamil problem will have remedied that omission after the worldwide publicity given to this week’s horrifying rioting. Horror is a terrorist’s credential. The Tamil hardliners are trying to shoot their way into the international club of terrorism which includes such accomplished practitioners as the Irish Provos, the Basque separatists, the Palestine Liberation Organisation and the Armenians.

The event that ignited the riots had an expert look about it. On a country road near the northern town of Jaffna last Sunday, July 24th, two jeeploads of soldiers ran into a landmine and were then shot down: 13 soldiers were killed. This produced counter-terror from the majority Singalese in which Tamil homes and businesses have been destroyed and at least 20,000 Tamils have been left homeless and an unspecified number dead. In the capital, Colombo, Tamils are said to have been dragged from their cars and incinerated with petrol. In the north the army, which is mainly Singalese, seems to have lost its temper, shooting Tamils indiscriminately. In two Colombo prisons several dozen Tamils were murdered by Singalese prisoners.

The Tamil problem has had a long fuse; there have been riots between Tamils and Singalese at regular intervals for a quarter of a century, although this week’s is almost certainly the worst. President Junius Jayewardene can reasonably claim that he was merely the unwilling inheritor of the problem. Through the establishment of regional development councils, he has ensured that the Tamil fifth of the population benefits equally with the Singalese in Sri Lanka’s promising, although still slow, economic growth. He has brought Tamils into his cabinet, and can point to an impressive number of Tamils in key jobs. The inspector-general of police is a Tamil.

But the Tamils’ demands have changed as the propaganda of bloody assertion ripples round the world. Their desire for some form of autonomy for the northern and eastern regions where Tamils are most numerous has been replaced by a demand for a separate state. This is the theoretical aspiration of the Tamil United Liberation Front, which despite its showy name is a moderate-minded political party with 17 members of parliament. And it is the explosively demonstrated objective of the guerrillas – the ‘Tigers’, as some of them call themselves – who have taken to the jungle.

An independent state carved out of Sri Lanka (which is smaller than Scotland) seems an absurdity. Although some Tamils claim that there was once a separate Tamil state, Eelam, historians doubt it. No boundary could be drawn which would contain all Tamils, since nearly half of them live in ‘non-Tamil’ areas. It is unlikely that many Tamil moderates believe in Eelam; but, under pressure to show that they can be as tough as the hardliners, they have refused to talk to Mr Jayewardene unless separation is on the agenda. Impasse.

The reopening of negotiations might be helped by a neutral mediator, preferably from Asia. Singapore, which Mr Jayewardene admires and which is investing a lot in Sri Lanka, could provide such a mediator. There is plenty to discuss as well as separatism, from relatively minor grievances like more university places for Tamils to the widespread Tamil feeling that they are considered a second-class people. This week has gone to the Tigers. It is conciliation that needs a success now.

Item 4: Bloodshed in paradise [Boston Globe, August 1, 1983]

The deeply rooted ethnic conflict that has led to rioting and bloodshed in Sri Lanka is a harsh reminder that a mixture of poverty with competing national ambitions can be explosive. A disheartening aspect of the fatalities reports so far in the island republic off the coast of southern India is that they seriously understate the loss of life, probably to be counted in the thousands rather than a hundred or so listed in official counts.

There will be no simple solution to the battle between minority Hindu Tamils, descended from 19th century immigrants from the mainland, and the majority, indigenous Buddhist Sinhalese population. The heavy loss of life among Tamils held as prisoners,71 at the end of last week,is a measure of the intensity of hostility between the government, dominated by Buddhist Sri Lankans and the Tamils.

Language, civil rights, access to jobs, political voice are all substantive issues on which the two factions simply cannot agree. With a per capita income of about $300 a year and heavy dependence on exports of such marginal commodities as tea, coconuts and rubber, the outlook remains bleak for the Sri Lankans despite the fact that they enjoy the highest literacy rate,85 percent,of all the developing countries. Foreign assistance thorugh the International Development Agency and the World Bank exceeds $800 million. These funds, designed to improve foreign exchange through increased tourism, are surely reduced in effectiveness by the spectacle of domestic violence.

Complicating the situation is the increasing intervention by the Indian government of Indira Gandhi, eager to protect the interests of the Hindu minority. The interest is understandable and to a degree legitimate but even under the worst of circumstances the rest of the world should make certain that the conflict is not used as a blind for establishing some form of domination of the Sri Lankans by the Indians. Whatever their abuses of the Hindu minority, the Sri Lankans are fully entitled to protection of their own nationhood.

The uprooting of thousands of people, the burning of shops and homes, the entrenchment of revenge as the driving political force behind the violence, guarantees that violence will remain a way of life for long time in Sri Lanka. The impulse to seek partition, familiar on the subcontinent, may be the only way to keep the rivalsout of each other’s way, but every effort should be made to avoid it. The government rules out partition, but has so far neglected full responsibility for making integration work.

For 15 million citizens of Sri Lanka, hope in the long run depends on cooperation and joint economic development to move out of the mutual poverty that afflicts Hindu and Buddhist alike. As remote as that may seem when Sri Lankans burn each other up in buses, it should not be lost as a target nor ignored by the rest of the world in whatever future efforts may be made to help Sri Lankans help themselves.

Item 5: Racism in Sri Lanka [Globe and Mail, Toronto, August 1, 1983]

Sri Lanka has been a model state in the Third World. Since becoming independent in 1948, it has been a democratic, genuinely non-aligned member of the Commonwealth. Despite its poverty, it has built a remarkable social welfare state of mass literacy, advanced health care and subsidized food rations. All the more tragic, then, that ethnic tensions have been allowed to boil over into mass violence that wreaks economic havoc, destabilizes democracy, and invites secession and outside (Indian) intervention.

Blame for the latest upheaval falls upon the ruling United National Party of President Junius Jayewardene who, since winning office in 1977, has tried valiantly to spur rapid growth with free market economics, but has failed to invest the same effort in resolving communal friction and now appears to be aggravating it.

In fairness, Sri Lanka’s fault line is not of Mr. Jayewardene’s making. It rests upon an historic enmity between the Buddhist, light-skinned, Sinhalese-speaking majority and the Hindu, dark-skinned, Tamil-speaking minority. The Tamils constituted the administrative elite, by virtue of their educational attainment, during British colonialism. Although a minority in Sri Lanka, the Tamils are part of a broader community of 50 million Tamils throughout southern India and southeast Asia. They evoked Sinhalese resentment on both counts.

Following independence, the Sinhalas turned the tables. Tamil was disestablished as an official language. Tamil students were required to obtain higher marks in university entrance exams, with the result that their enrollment fell drastically and opportunities for study abroad declined. There was discrimination against Tamils in recruitment and efforts were made, and still continue, to move Sinhalas from the seven over-populated provinces where they dominate to the relatively under-populated Tamil provinces of the north and east. The majority’s Buddhist faith was emphasized as the state religion.

Despite these discontents, nationalist feeling among the Tamils did not crystalize as separatism until 1976, when the Tamil United Liberation Front adopted a resolution calling for a separate state (eelam) in the north and east. Its methods were peaceful, however, and the election which brought the UNP to power in 1977 also made the TULF the main opposition party.

President Jayewardene did make an effort to conciliate the Tamils, providing for the ‘reasonable use’ of the Tamil language in public life in the north and east, while decentralizing administration through the creation of 24 district councils. The TULF co-operated in the devolution move, despite extremist pressures on its flank by the terrorist Tamil Tigers.

The initiatives proved too little, too late, though, and Mr.Jayewardene, pressured by extremist opinion within his own party, has taken an increasingly hard line, prompting recent criticism by Amnesty International for the use of torture against suspected Tamil terrorists. Now, by announcing his plans to outlaw even parties committed to peaceful separatism, he risks dealing a body blow to Sri Lankan democracy while providing more recruits for ‘direct action’ by the disaffected minority.

For Canadians, it is a disturbing confrontation. We are giving substantial aid to Sri Lanka and receiving a wave of Tamil exiles. We can only hope Sri Lankans have not reached the flashpoint of two nations warring in the bosom of a single state.

Item 6: Tremors in Sri Lanka [Washington Times, August 3, 1983]

Scenes of burning buildings, dispirited victims of rioting, and patrolling troops in news reports from Sri Lanka probably forced many Americans to pause and think, ‘Oh, yes, Ceylon, the Indian Ocean, that place.’

No doubt Sri Lankans would flinch at the mental pause to place their country, but its inconspicuousness over recent years may be an enviable mark of its relative stability and quiet development – and, in that sense, no bad thing. But the eruption of violence between the majority Sinhalese and the Tamils, which has taken more than 200 lives so far, is an ominous indicator of greater danger to the island nation – internally and, the government in Colombo worries, from outside.

Sri Lanka has done a commendable job of maintaining free speech and free enterprise in a world where neither is the norm. But the Tamils, of Indian origin, have been the victims of viciousness periodically in the past 25 years, and a tenacious separatist movement has grown in the country. Communal violence is always appalling, the more in a nation which has been laboriously traveling the rough path of development. This latest explosion of fighting comes, however, as Sri Lanka has been trying to insure that the Tamils benefit from national progress. President Junius Jayewardene has appointed Tamils to his cabinet and members of the ethnic minority to substantial government jobs. Thus, it may seem paradoxical that separatist emotion should boil so fiercely.

Or not paradoxical: The government has complained darkly, and not implausibly, that the rioting was fomented by ‘one of the great powers’. And guess which one isn’t referred to, gang! Jayewardene has clamped down quickly on three leftist political parties, including the communist, and members of the groups have been arrested. There are reports as well that the Soviets may be told to send home some of their numerous commercial and cultural attaches.

Added to suspicions of internal subversion (the initial rioting broke out after a quite professional ambush of a military patrol), Sri Lanka is also apprehensive that India, 20 miles away across the Palk Strait, might think it incumbent to aid the Tamils. Thus, Jayewardene has appealed to the U.S., Britain, Pakistan and Bangladesh for military aid in case of a foreign invasion. It is difficult to imagine that India would be so foolish, but it’s just as well that Sri Lanka is thinking about such a contingency. The world can do without another nasty explosion, especially in that part of the world.

Item 7: Sri Lanka Torn [Washington Post, August 5, 1983]

Sri Lanka, the island nation south of India that has had success in recent years practicing democracy and free enterprise, blew up the other day. The Sinhalese majority took out after the Tamil minority, killing hundreds, leaving tens of thousands homeless, inflicting economic damage in the hundreds of millions of dollars and causing the nation’s prospects to shrivel almost overnight. Everybody knew – for centuries – there was bad blood. Nobody seems to have anticipated an explosion on this scale. A country headed up, despite everything, is heading down.

In Sri Lanka (Ceylon until 1972), American missionaries from Boston educated the Tamils, who came from India in the early 19th century to work on the tea plantations. This was one factor contributing to the Hindu Tamils’ advancement in a society otherwise dominated by Buddhist Sinhalese. (It also apparently accounts for the resolution in the Massachusetts legislature denouncing Tamil repression.) There has been trouble for a long time, although the country knew periods of relative communal harmony, too. In the latest episode, Tamil separatist guerrillas ambushed a patrol of Sinhalese soldiers. Riots broke out. The Sinhalese army seems, at best, to have stood by.

Everywhere in the world different ethnic groups find themselves sharing a single set of national boundaries. Why can they get along passably well in some times and places and not in others? It is easy enough for outsiders to urge the Sinhalese and the Tamils to put aside their differences and work together for their common good. But other currents are running. The president is well thought of but he has an inflamed constituency to answer to. Citing a danger of Tamil secession, he has closed out Tamil representation in Sri Lanka’s elected parliament, a move whose likely effect will be to still the remaining moderate Tamil voices and leave the field to the guerrillas. The ‘Tamil Tigers’, who have been helped by the PLO in the past, have India’s Tamil province nearby for auxiliary sanctuary.

If living together is so hard, what about a separate state in the north for the Tamils? They have as good a claim to a nation of their own as most members of the United Nations. But as always it is a question of power, and in Sri Lanka the Sinhalese have the power. Do they also have the wisdom to see that the Tamil minority is treated in a way that justifies its retention within a unitary state?

Item 8: Not just the Tamils [Economist, London, August 6, 1983]

In Utopia there are no barriers of class, creed, culture or colour. In the land of harmony, differences exist not to divide and inflame but to embroider more richly the tapestry of life. Tamils and Singalese, Armenians and Turks live happily together, respecting each other’s traditions, learning from each other’s cultures.

Utopia does not exist, nor ever will. Nationalism, that irrational and generally false sense of family superiority, reigns supreme – especially where people who feel markedly different from each other are required to share the same island, or to form governments on the same patch of land. Nationalist prejudice is as old as the Ark and the going of Noah’s sons on their separate ways. What is shocking to the modern mind is that, as education advances across the world, rabid nationalisms show no sign of diminishing. Singalese and Tamils continue to kill each other as surely as obsessed Armenians kill Turks, and Irishmen of different nationalist allegiance kill each other.

There are no general prescriptions, only a need to face facts. False expectation makes matters worse. Many countries – perhaps a majority – are lumbered with deep ethnic tensions. The plague of nationalism is most repetitiously oppressive in Africa (where it is better known as tribalism). There, several thousand tribe-nations once enjoyed some sort of political autonomy in the pre-colonial age. Then came their involuntary quashing into a mere 50-odd states (the precise number is under debate: no prizes for guessing why). It was absurd to hope that many of the African nations thus flung together would live in harmony.

In the flush of post-independence optimism, many believed they could. Now it is clear that for the most part they cannot. No need to be censorious. Why should a Yoruba and a Hausa be expected easily to share a single country when such close relations as Irish and Scots, or Poles and Russians, or Serbs and Croats, find it so hard?

Ideology, for sure has proved no unifier. The advance of a cohesive international communism, apparently unstoppable 40 years ago, has petered out in the marshes of nationalism. Ancient Russian and Chinese nationalisms have proved far more decisively potent than the unifying proleterian internationalism preached by Marx. It is astonishing how rapidly the nationalismsof south-east Aia – of Khmer and Vietnamese – overwhelmed the ideology that was said to bind these peoples together against the French and the Americans.

Economics, say others, is the vehicle of unity. Peoples will eventually be wedded by the blessings of a shared market. Petty tribal animosities will evaporate as men and women realise that only in increasingly larger units can they benefit from the miracles of technology, and from the flow of trade and ideas. Nineteenth-century European experience seemed to prove this, with a host of German and Italian statelets coalescing fairly painlessly into the larger entities of today. Nigerians, it can be argued, should now strive for the same goal. Africa divided into a thousand statelets would equal chaos and even greater penury. Yet the currently accepted alternative – Africa lumped together in 50 artificial compartments – is proving a recipe for political instability, which helps to prevent economic growth.

The traditional riposte to these gloomy generalities is that sensible men can create, out of diversity, the magic condition known as consensus. People will come to understand that there is more to lose by sticking apart than by jostling together, however awkwardly. If separate national traditions refuse to die, they can surely be accomodated under one benign umbrella. Alas, the rosy examples are scant. Cyprus, Ireland? India at the end of the Raj? Ethiopia after Menelik the Great? South Africa after apartheid? Sri Lanka in 1984? There are some pretty fragile examples of hesitant multi-national harmony, such as India; but precious few.

The multi-national options fall four ways. There is absorption, the wholesale merging of lesser tribes with greater ones. There is centralised despotism, sometimes benevolent, often not. There is the gentleman’s option, federalism – most attractive but also the most awkward of the lot. And there is partition, which carries the stigma of failure.

Absorption is neatest. Different groups are simply melted in a supranational pot – the United States, for instance, with its winning concoction of one predominant language, one predominant culture (Anglo-Saxon spiced with practically every other European tradition), one main religion and one ideology (rampant individualistic materialism mitigated by the humanism of Jefferson and Lincoln). Brazil could yet prove a vivid modern example.

Despotism is the norm. In countries – most obviously, African ones- whose inhabitants have no shared history or identity, a strong force must emerge at the centre to hold the parts together. Stalin and his successors have known how. Quite a fewable post-colonial African leaders – Kenyatta and Nyerere, for instance, in their very different ways – have managed to straddle their bundle of mini-nations, creating a plausible illusion of nationhood. Others – Obote in Uganda, Mengistu in Ethiopia, Mobutu in Zaire – have been unable to prevent key components (the Baganda, the Eriterians the Katangans) from trying to secede.

Secession, especially in Africa, has been understandably taboo. If one bit falls away, hundreds more will clamour to follow. But as time passes there is better cause for the taboo to be broken. If Chad, for instance were broken into two or three, its inhabitants could only fare better in more homogeneous units. The artificial boundaries bequeathed by France have provided bloodshed and disunity.

The stock multi-national democratic compromise is federalism. That option requires checks and balances that often need a strong centralising force – a great leader, maybe, or a common enemy – and a measure of restraint and consensus among the component parts. Bud federations have often been cobbled together precisely because consensus is lacking. The success of Nigeria’s experiment is still touch-and-go. Even more sophisticated Jugoslavia, without Tito, is at risk. Third world federations sound nice but rarely work.

When federalism fails, and despotism cracks, all that is left is the option of partition – the ultimate in political failure, it is said. And yet…After all the bloodshed of 1947, is it likely that an unpartitioned India would ever have been viable? Can Turks and Greeks ever live harmoniously together on an independent island? Are Rwanda and Burundi, now partitioned into tribal units at the costof near-genocide, not better off in two or more homogeneous parts?

Yes, resort to partition is an admission of defeat. The horrifying corollary of partition, if it is to be effective, is often a huge deportation or even massacre. (Partition in Ireland has been ineffective because there was no such brutal demographic alteration.) If the Tamils were to have a northern autonomous state on Sri Lanka, two or three million people might have to be uprooted. The prevailing wisdom is that Singalese and Tamils must somehow learn to share one government on one island. But the bitter and growing lesson is that such things are sometimes impossible.

Item 9: Tormenting the Tamils [The Observer, London, August 7, 1983]

As ethnically divided islands go, Sri Lanka has had a relatively peaceful history,being associated in the public mind with up-market package holidays rather than inter-communal violence. Lamentably, that is not the case now- after the deaths of about 300 people and the destruction of hundreds of houses, shops and factories by rioters and looters.

As with Cyprus, the roots of the problem are traceable to the days of British colonial rule, since when the hatreds which have now broken surface have been smouldering with increasing intensity. The minority Tamils, against whom the violence is now being perpetrated, were promoted by the British to top jobs in the Civil Service and in business. The Tamils, whose homes are in the northern, more arid part of the island, where the agricultural way of life is no easy option, accepted this favoured treatment with alacrity. As a result, the majority Sinhalese approached independence determined to have their revenge. They chipped away first at the privileges and then at the basic rights of the Tamils.

The language and sectarian policies of successive governments in Colombo have led to a sharp fall in the recruitment of Tamils to posts in the government, which in Sri Lanka, as in many other Third World countries, is the principal employer. Between 1956 and 1970, for instance, the proportion of Tamils in the administrative service declined from 30 percent to 5 percent. The proportion of Tamils in Sri Lankan universities has also dropped dramatically. The constitutional provision for ‘reasonable’ use of the Tamil language in limited areas has become a dead letter. It is no surprise that many Tamils now believe that the only answer is partition.

Unfortunately, the reaction of President Jayawardene so far can only exacerbate the problems. On Friday he used the big parliamentary majority United National Party to pass an amendment to the constitution which appears to outlaw the leading Tamil party, the Tamil United Liberation Front (TULF). The amendment imposes severe penalties on any person or party advocating the division of the island into separate homelands. This is the official policy of TULF. The President has also been blaming the Tamils themselves for the violence, failing to make a distinction between the majority of peace-loving Tamils and Tamil Tiger guerrilla groups who have committed acts of violence.

By these actions President Jayawardene gives the appearance of condoning the outrages committed against the Tamils in recent weeks. The effect will be to drive more Tamils towards the terrorist groups. There is some hope in the decision to set up a new ministry to handle relief and rehabilitation work. It must act generously and impartially. But, if the drift towards civil war is to be halted, President Jayawardene must come down firmly on the side of political reconciliation.

Item 10: Unhealthy Intolerance [Globe and Mail, Toronto, August 8, 1983]

Having finally restored a measure of calm to his riot-scarred nation, President Junius Jayewardene of Sri Lanka should be seeking ways to remove inter-communal bitterness and prevent fresh eruptions. Instead, his first move is one that seems certain to exacerbate tensions and radicalize the leadership of the Tamil minority.

Legislation introduced in Parliament the other day by his United National Party would outlaw any political party which preaches separatism, even by peaceful means. The constitutional amendment aims not at the terrorist Tamil Tigers, which are already outlawed, but at the more moderate Tamil United Liberation Front, which is the main opposition party in Parliament. To appreciate the consequences of this arbitrary action, it is worth considering what the future course of English-French relations might have been in Canada if the federal Government had responded to the 1970 Quebec Crisis by banning not only the violent separatism of the Front de Liberation du Quebec, but also the evolutionary separatism of the Parti Quebecois.

The comparison is not an exact one. Whereas Quebec enjoys provincial autonomy with which to defend the status of francophones in the Canadian federation, the Tamils have no such autonomy, even in the northern and eastern provinces which they dominate, because the Sinhalese hardliners within the UNP frustrated Mr.Jayewardene’s attempt at decentralization. Ironically, the TULF co-operated in the passage of the devolution legislation despite extreme pressures on its flanks. Had an effective autonomy for the Tamils been implemented, the TULF likely would have soft-pedalled its commitment to outright independence. Now, the party is to be rewarded for its relative moderation by being driven underground. The Tamil Tigers, who number only 200 guerrillas, will have a new source of recruits.

Mr.Jayewardene’s action is disturbing not only because of its insensitivity to the Tamils, but because it is further evidence of his readiness to emasculate any significant parliamentary opposition to his UNP. In 1980, when he stripped former prime minister Sirimavo Bandaranaike of her political rights for six years, he set in motion the virtual collapse of her Sri Lanka Freedom Party, leaving only the TULF with a sizable bloc of seats in Parliament. The ‘banning’ of Mrs.Bandaranaike (for having abused the authority of her office) is unexceptionable from a legal point of view, as is the banning of the separatist parties. But taken together, these actions suggest that Mr.Jayewardene has a low tolerance for parliamentary opposition and an unhealthy appetite for unimpeded authority.

There was a time when he seemed less addicted to power. Following an earlier wave of anti-Tamil rioting in 1981, he chastised members of his UNP whohad incited hatred. ‘I must have reason to be proud of the party of which I am leader,’ he warned. ‘If I cannot it is better for me to retire and let those who believe that the harming of innocent people and property…is the way to solve the problem that faces this multi-racial, multi-religious and multi-caste society take over the leadership of the party.’

But instead of reading Sinhalese extremists out of the UNP, Mr.Jayewardene has become their reluctant captive. Outlawing the public espousal of separatism may satisfy the majority by affirming the indivisibility of Sri Lanka, but it will do nothing to heal the underlying ethnic breach.

*****