by Sachi Sri Kantha, March 1, 2025

Introduction

Yellow Anaconda, featured in Salamandra journal (2020)

Many may be unaware that the etymological origin of the English word ‘Anaconda’ is rooted in two Tamil words, used in Ceylon in the 17th century, for a python snake. The stimulus for my investigation was a mischievous entry in the ‘Facts on File Encyclopedia of WORD AND PHRASE ORIGINS’ by Robert Hendrickson (b. 1933), 3rd edition (2004). It read as follows:

“anaconda. This is one of the few English words, if not the only, that comes to us from Singhalese. Anaconda probably derives from the Singhalese henakandaya, although this word means ‘lightning stem’ and refers to Ceylon’s whip snake, not the large snake we know as the anaconda. Weekley notes that ‘the mistake may have been due to a confusion of labels in the Leyden museum.”

The authority referred by Hendrickson was Ernest Weekley – Etymological Dictionary of the English Language (1967). I checked the original edition of this work, published in 1921 (London John Murray). This is what is provided in p. 45.

“anaconda. Orig. large serpent found in Ceylon, anacandaia (Ray). Now used vaguely of any boa or python. Not now known in Singhalese, but perh. orig. misapplication of Singhalese henakandaya, whip snake, lit. lightning-stem. It has been suggested that the mistake may have been due to a confusion of labels in the Leyden Museum, Ray’s source for the word .”

Well, my zoological instinct provoked me, that something is twisted in this entry! Reason: lexicographers and etymologists do meaningful studies in word origins, but they also have their blind spots in areas they are not familiar with. For example, biological sciences and animal behavior. Quite a number of vernacular names are mostly derived from lay people’s field observations of a particular animal’s surroundings, behavior, and how they behave as predators.

Here is my report on untangling this etymological twist in the ‘anaconda’ word. The purported Tamil root of ‘anaconda’ is a corrupted appellative of two adjectival words ‘aanai-kondra’ or ‘aanai-konda’. In Tamil, aanai = elephant, and kondra or konda = [the one that kills]. The common name for this python in Tamil is ‘Periya Paampu’ (big snake) or ‘Malai Paampu’ (rock snake).

ANACONDA

Anaconda (now classified as belonging to the Boidae family of snakes; etymology, from Latin; According to Frank Wall (1921) ‘Boa is derived from Latin [root ‘bos’ a cow, and is based on the old fable that some, or one, of the species sucked the milk from cows. And Roman historian Pliny (AD 23-79) had mentioned this story.’ A link to basic reference on Anaconda is available in the net, from the venerable National Geographic magazine.

https://kids.nationalgeographic.com/animals/reptiles/facts/anaconda

This type of snake lives in the South American continent. Strangely, the English name Anaconda was derived from the original specimen then available at the Leiden Museum, from island Ceylon! Currently prevalent zoological genus name for anaconda is Eunectes [Greek, eu= true or good; nectes – swim]

As the the appellative ‘aanai – kondra’, links Ceylon python to one of its prey (the elephant), the elephant lore in Ceylon also deserves a check. Most usually, baby or adolescent elephants would have been attacked. The most popular elephant-related place name in Sri Lanka is, ‘Elephant Pass’ in the Northern district. In Tamil, it is ‘Aanai Iravu’ (Aanai = elephant, Iravu = death!). Another popular elephant-related place name is the Anawilunduwa wetland sanctuary, located between Puttalam and Chilaw. Though the name had become Sinhalized now due to ethnic mingling, the etymology is clearly Tamil. (Aanai = elephant; vilundu= fall). Make a note that the Sinhalese word for elephant is ‘aliya’ or ‘gaja’ (derived from Sanskrit). As such, I explore the origin of anaconda word from five angles.

- Linguistic and lexicographic data

- Python lore in Ceylon, during the British period (late 19th century)

- Elephant lore in Ceylon, during the Dutch period (1640-1795)

- Anaconda scholarship

- American political lexicon

- Linguistic and lexicographic data

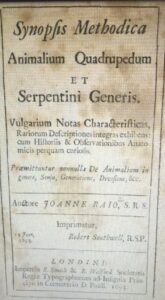

John Ray’s 1693 book cover

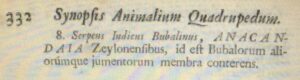

Earliest mention of the anaconda word appeared in the1693 compendium Synopsis Methodica Animalium uadrupedum et Serpentini Generis, of English naturalist John Ray (1627-1705), published in London (page 332). The language is Latin. Please check the two images, provided nearby.

Item 8. Serpens Indicus Bubalinus ANACANDAIA Zeylonensibus, id est Bubalorum aliorumque jumentorum membra conterens.

Then, in chronological order, I list the documents which I had checked for details on anaconda.

Encyclopedia Britannica, 1st ed. 1771 – no entry on Anaconda.

Encyclopedia Britannica, 2nd ed. 1777 – no entry on Anaconda.

Encyclopedia Britannica, 3rd ed. 1797 – carries an entry on Anaconda (vol.1, p. 648). The description given was “ANACONDO, in natural history, is a name given in the isle of Ceylon to a very large and terrible rattle snake, which often devours the unfortunate traveler alive, and is itself accounted excellent and delicious fare.”

Encyclopedia Britannica, 4th ed. 1809 (vol.2, part 1, p. 166) and 5th ed. 1815 (vol.2, p.166) has the same details, as given in the 3rd edition of 1797, and adds a shorter sentence “It is probably a Boa constrictor”.

Encyclopedia Britannica, 14th ed. 1947 (vol.1, p. 859).

“ANACONDA (Eunectes murinus), an aquatic boa, inhabiting the swamps and rivers of Brazil, northeastern Peru and the Guiana in South America. It is the largest of American snakes and rivals the reticulared python as the largest snake in the world. Exaggerated tales have been told by travelers of its size and swallowing capacity, but the largest known do not exceed 30 ft. in length. There is very great dread of this snake among the natives, though authenticated cases of its having attacked man are few. The general colour of the anaconda is olive-brown, with large oval black spots arranged in two alternating rows along the back, and with smaller white-eyed spots along the slids. The belly is whitish, spotted with black. The head is elongate, flat, and very distinct from the neck. The nostrils are situated between three large shields. The anaconda feeds chiefly at night, upon birds and other animals, which it kills by constriction.

Good sized specimens of the alligator like caymans are regularly killed and eaten by the anaconda. In contrast to the boa constrictor, which rarely takes to the water, the anaconda spends most of its time there, lying entirely submerged, with only a small part of its head above the surface, waiting for any suitable prey. Only seldom does its establish itself in the branches of trees like the boa. It is ovoviviparous and the young are about 36 in. long when born.

John Ray’s 1693 mention of Anacandaia Zeylonensibus snake

Compared to the information provided in the Encyclopedia Brittanica, even in 1947, more information was provided by Henry Yule and A.C. Burnell’s 1886 dictionary – Hobson-Jobson: A glossary of colloquial Anglo-Indian Words and Phrases, and of Kindred Terms, ethnological, historical, geographical and discursive (London Routledge & Kegan Paul). A new edition of this was published in 1903 (London: John Murray), under the guidance of William Crooke. I excerpt relevant details, spread over pages 23-25, below.

“ANACONDA: This word for a great python, or boa, is of very obscure origin. It is now applied in scientific zoology as the specific name of a great S. American water snake… In fact the oldest authority that we have met with, the famous John Ray, distinctly assigns the name, and the serpent to which the name properly belonged, to Ceylon. This occurs in his Synopsis Methodica Animalium uadrupendum et Serpentini Generis, Lond. 1693. In this he gives a catalogue of Indian serpents, which he had received from his friend Dr Tancred Robinson; and which the latter had noted e Museo Leydensi. No. 8 in this list runs as follows:

‘8. Serpens Indicus Bubalinus, Anacandaia Zeylonensibus, id est Bubalorum aliorumque jumentorum membra conterens,’ ….

We have the authority of Ray’s friend that Anaconda, or rather Anacondaia, was at Leyden applied as a Ceylonese name to a specimen of this python. The only interpretation of this that we can offer is Tamil aanai-kondra [aanaikonda], ‘which killed an elephant’; an appellative, but not a name. We have no authority for the application of this appellative to a snake, though the passages quoted from Percival, Pridham, and Tennent are all suggestive of such stories, and the interpretation of the name anacondaia given to Ray ‘Bubalorum…membra conterens’ is at least quite analogous as an appellative.”

Toward the end of this entry, “A more plausible explanation is that given by Mr. D. Ferguson (Notes & Queries, xii, 123) who derives anacandaia from Singhalese Henakandaya (hena, ‘lightning’; kanda, ‘stem, trunk’) which is a name for the whip-snake(Passerita mycterizans), the name of the smaller reptile being by a blunder transferred to the greater.”

I, for one, find it difficult to accept this Sinhalese derivation of anaconda, for the following reasons. First, the original authors of the Hobson-Jobson glossary were Col. Henry Yule (1820-1889) and Arthur Burnell (1840 – 1882). When this glossary was published in 1886, Burnell had died, and it was he who was the spirit behind this glossary and had worked at the Madras Civil Service and was a scholar in Dravidian languages. Co-author Col. Yule had spent few years in the North India, mainly Calcutta, and in his later years settled down in Palermo, Sicily. So, it could be safely assumed that Col. Yule was not adept in Dravidian languages. Secondly, following the death of Col. Yule in 1889, a second edition appeared in 1902; this was edited by William Crooke. And the Sinhalese derivation from Mr. Donald Ferguson (1853-1910) was subsequently added, following its appearance in Notes and Queries journal in 1897 (vol. 12, pp. 123-124). In his preface to the 2nd edition, Crooke had included Ferguson’s name as one of his numerous consultants. Thirdly, available biographical details of Donald Ferguson doesn’t provide confidence about his Tamil proficiency. Born in Colombo, Ferguson and was an editor of the Colombo Observer newspaper, but due to health problems, retired to England in 1893 and died in 1910. Though it may be assumed that Ferguson would have learnt Sinhalese, his proficiency in Tamil is questionable. More dubious was his expertise in zoology. Even in the introductory remarks to the Hobson-Jobson glossary in the first edition, Col. Yule had specifically stated ‘The Indian zoological terms were chiefly due to Dr. F. Buchanan, at the beginning of this century.’ This was Scottish surgeon, Dr. Francis Buchanan (1762-1829), who had lived in India, from 1794 to 1815.

In fact, the Sinhalese word ‘pimbera’ for Ceylon rock python was recorded in Charles Owen’s 1742 book ‘An Essay towards a Natural History of Serpents: in two parts’ (London, privately printed). In page 90 of this book, Owen had written the following:

“In Ceylon in the East Indies, they have many species of serpents; as

XXIII. The Pimbera serpent, whose body is said to be as big as a Man’s middle, and in length proportionable. The creatures of this kind secure their prey, even horned beasts (which sometimes are pretty large) by a sort of a peg, or pointed hook, that grows upon the extremity of the tail They are slow in motion, and therefore skulk in hollow places; and when they have taken the spoil, tho’ horned, they swallot it alive, and whole; which often proves fatal, because the horns may gore the belly.”

This could be the first description in English for the Ceylon rock python. To rebut the Sinhalese derivation of anaconda, I provide details of this snake below, from two British authors of books on snakes of Ceylon.

- Python lore in Ceylon during the British period (late 19th century)

Abercromby was the first Britisher to publish a book on snakes of Ceylon, in 1910.

In a few pages, he described python hunting and the role of five ‘coolies’. Literal meaning of this Tamil word ‘coolie’ is, ‘wage’. It is obvious, that this derogatory epithet by the British colonials refers to Indian Tamil labor migrants. And their native tongue was/is Tamil, and they would have used ‘aanai –kondra or aanai-konda’ in their colloquial tongue, rather than the Sinhalese word ‘henakandaiya’.

For its interest, I provide Abercromby’s description of python hunting techniques, in full. It is ~1,200 words long.

“The Python is extremely difficult to obtain when required, and often much patience, enquiry and hard work is necessary before a specimen is obtained. It is of course necessary to know something about the habits of a snake before attempting to catch it; I therefore append a brief account of its manner of hunting when it its wild state.

Ceylon Rock Python (or Malai Paampu, in Tamil) Python molurus

There is only one variety of Python found in Ceylon – the Python molurus. It inhabits swampy districts and places where there is a heavy rainfall, and is often found lying in jungle ponds with only its nose exposed above the water.

As the sun begins to set the snake glides from the water. There is no noise, only a track of crushed grass to show where the Python has been. It reaches the jungle and its yellow and black skin blending with the shadow and sunlight, disappears.

A deer comes down the game track on its way to the pool to drink. The small clump of long grass arouses no suspicion, not being large enough to conceal a leopard.

Yet within that clump the python lies coiled like a spring, its flat head slightly raised, and its powerful neck curved back, ready to make the lightning stroke.

The deer approaches and reaches the grass. A flash of yellow, a choking cry, and it lies gasping its life out in the deadly coils of the Python which has seized it, rolled it over, and wound round it like cotton round a reel. A little more gasping and it is over. Slowly the coils relax, and the flat pink head shakes its teeth loose of the deer’s throat. Then slowly and deliberately the Python starts to move its nose over, under and about the deer, salivering it, so as to digest it easily. This occupies ten minutes or so, then the swallowing commences. Grasping the deer by the head, and flinging its coils over the body, so as to break the bones, first one side of the jaw is projected and then the other. Caught by the hooked teeth, the deer slowly, very slowly, is drawn down the snake’s throat, being again crushed in the process by the muscles of the gullet, the Python’s mouth being at this time extended to nearly twice its normal size.

Half an hour passes, and the Python, much distended about the centre of the body, fades again into sunshine and shadow to sleep off its meal.

The Python may be obtained in several ways, but it is, of course, necessary to choose the right type of country to hunt in. The wide stretches of grass and scrub lying between a ‘tank’ (artificial lake) and the large surrounding jungle, are perhaps the best, not because there are likely to be most pythons there, but that if there are any, you are more likely to see and catch them in such a country. The place chosen, must of course, be beyond the disturbance of civilization.

The evening is the best time for python-hunting, especially after a shower of rain, and you may employ two methods. One is to walk quietly along the game-tracks just inside the main jungle (the edges of the jungle are more accessible than the interior, and there is less likelihood of getting lost, with greater facilities for the capture of any snakes seen and required). A sharp look out should be kept along the game tracks and under the bushes and undergrowth, for any python that may be lying in wait for game that is going down to the ‘tank’ to drink, or is sleeping stretched out across a path, after a gorge.

A python when disturbed, and retreating through the jungle, makes a noise resembling the dragging of heavy sacks along the ground. If alarmed, and moving rapidly, when approached, it must be seized by the tail, and an attempt made to press its head against the ground with your foot, or if accompanied by a coolie, a stick can be placed by him across the snake’s head. It should then be taken and held by the neck with one hand and by the tail with the other. Of course it will attempt to bite, and when seized will attempt to crush, but this sort of thing has to be chanced, and adds to the excitement, for there is a certain amount of excitement, especially with a large python, but it does not do to get excited.

The way to capture a python, without injury either to oneself or the python, cannot be explained, but can only be learnt by practice, and even then there is the likelihood of being bitten,

Except in the case of a very large python, there is no danger, though the latter is capable of inflicting a very severe bite, tearing up the muscles with its curved teeth, and probably disabling the member bitten for some time to come. If, when catching a python, you are seized by it, you should at once release your hold of the snake, when it will in all probability leave go of you, in order to escape.

If the snake is found asleep in the jungle, it can often be captured without any trouble, if approached quietly and seized suddenly. It is easiest to catch a python after it has had a meal, as it is less liable to strike or try to escape.

Another method of catching these snakes is to set out in the evening, accompanied by some coolies, and beat the land round the ‘tank’ in the following manner: The coolies should walk in an oblique line, stretching from the tank to the jungle, and should move parallel as much as possible with both. Taking the space to be covered (between tank and jungle) to be 100 yards in width the first coolie should move alongside the tank, and a few yards from it. The second coolie should be about 25 yards away (to the side) of the first coolie, and about 5 yards behind him, the third coolie should be 25 yards from the second, and five yards behind him, the fourth coolie should be 25 yards away from the third and five yards behind him, and the fifth – the person who is to catch the snake – should walk alongside the jungle.

The first two men should make a certain amount of noise, the other two should be comparatively quite; the man by the jungle should be as silent as possible.

Any snake that may be drinking water, or catching frogs, by the side of the ‘tank’, will, on hearing the first man approach, make a fairly straight line back to the jungle. The first man will at that time be about eight yards from the snake, and the man near the jungle will be twenty yards behind the line of the first man. The snake will probably retreat at a rate of from six to seven miles an hour, or perhaps a little less, and as the men will be walking at a pace of two miles an hour, the snake will pass within a few feet of the man near the jungle, who will attempt to catch or kill it, as the case may be.”

The second author was Frank Wall (1868-1950). Compared to Abercrombie’s book, Wall provides more details on rock python in his 1921 book ‘Ophidia Taprobanica or the SNAKES OF CEYLON’ (pages 48-63). But, in the footnote item, Wall seems confused about the ‘aanai-kondra’ phrase, and misidentified it as Sinhalese! This is the pitfall – As opposed to journalists and etymologists who may be competent in linguistics but deficient in zoological knowledge, zoologists (especially non-natives like Wall) know only their territory but are ignorant on linguistics! This is what Wall had described, spelling errors stand uncorrected:

“According to the famous John Ray the word anaconda is Sinhalese, [note by Sachi: This itself is wrong, because Ray had only mentioned the word ANACANDAIA in Latin – see the image nearby. He did not mention anything about Sinhalese!], and not South American as one might suppose. His friend Dr. Tancred Robinson gave him a catalogue of the Indian snakes he had noted in the Leyden Museum. No. 8 on this list read as follows:- ‘8 serpens indicus bubalinus anacondaia zeylonibus, idest bubalorum aliorumue jumentorum membra conterens.’ Yule says he can find no mention of the name anaconda in old South American literature, and suggests that it is derived from the Sinhalese ‘anai’ elephant, and ‘kondra’ which vanquished. I am told that the Tamil is ‘anai’ elephant, and ‘kolra’ killer.”

- Elephant lore in Ceylon, during the Dutch period (1640-1795)

Richard Gerald Anthoisz (1852-1930), in his 1929 book ‘The Dutch in Ceylon’ provides a paragraph about elephant culling during the Dutch period. To quote,

“The subject next in importance to cinnamon as a source of profit to the [East India] Company was the trade in elephants. For the capture of these animals, also, a distinct class of people had from ancient times been set apart. The elephant hunt was carried out on under the authority of the Dessave of Matara with Manampey Arachchi directly under him, assisted by 4 headmen or vidanes…The 4 vidanes and headmen were bound to deliver yearly 84 elephants, of which 4 must be tuskers. This number could not however be reached so far owing to certain difficulties. Twenty two animals realized 18,652 rix dollars…”

To cite a paragraph from a recent report by Jayantha Jayewardene, captioned ‘History and culture of elephants in Sri Lanka’ [Gaja, 2006; 24 57-60],

“Pybus (1762) states that the Dutch had to obtain permission from the kind of Kandy to capture elephants which were within his domain. The kind generally agreed to the Dutch capturing 20 to 30 animals each year, but the Dutch constantly exceeded this figure, capturing around 150 each year and 200 in one year. They continued to use the elephant stables at Matara. Elephants were also exported by the Dutch from Karativu island. The elephants were driven into the Jaffna peninsula by a shallow ford that separated it from the mainland. This ford has now been bridged and given the name Elephant Pass.”

Now, one can comprehend the sense of the Tamil name Aanai Iravu (Elephant death) for Elephant Pass. Based on the description provided by Ambercrombie’s python lore (provided above) about rock pythons lurking in the waters of ‘tanks’ in the Vanni region which could have attacked the elephants driven towards Jaffna annually, quite a number of elephant casualties could have occurred in the 18th century. Thus, the adjectival Tamil appellation ‘Aanai-konda’ is indeed fact-based, for Ceylon rock python.

- Anaconda scholarship

Henry Walter Bates (1825-1892)

One of the prominent records, available about Anaconda’s habits in the Amazon river was from British naturalist Henry Walter Bates (1825-1892), a junior contemporary and pal of Darwin. In his ‘The Naturalist on the River Amazons’ (originally published in 1863), Bates had recorded the following in two paragraphs, from entry dated August 5 [1852]..

“We had an unwelcome visitor whilst at anchor in the port of Antonio Malagueita. I was awakened a little after midnight, as I lay in my little cabin, by a heavy blow struck at the sides of the canoe close to my head, which was succeeded by the sound of a weighty body plunging into the water. I got up; but all was again quiet, except the cackle of fowls in our hen-coop, which hung over the side of the vessel about three feet from the cabin door. I could find no explanation of the circumstance, and, my men being all ashore. I turned in again and slept until morning. I then found my poultry loose about the canoe, and a large rent in the bottom of the hen-coop, which was about two feet from the surface of the water: a couple of fowls were missing. Senhor Antonio said the depredator was a Sucuruju (the Indian name for the Anaconda, or great water serpent – Eunectes murinus), which had for months past been haunting this part of the river, and had carried off many ducks and fowls from the ports of various houses. I was inclined to doubt the fact of a serpent striking at its prey from the water, and thought an alligator more likely to be the culprit, although we had not yet met with alligators in the river. Some days afterwards, the young men belonging to the different parties, each embarked in three or four canoes, and starting from points several miles apart, whence they gradually approximated, searching all the little inlets on both sides the river. The reptile was found at last, sunning itself on a log at the mouth of a muddu rivulet, and despatched with harpoons. I saw it the day after it was killed; it was not a very large specimen, measuring only eighteen feet nine inches in length, and sixteen inches in circumference at the widest part of the body. I measured skins of the Anaconda afterwards, twenty one feet in length and two feet in girth. The reptile has a most hideous appearance, owing to its being very broad in the middle and tapering abruptly at both ends. It is very abundant in some parts of the country; nowhere more so than in the Lago Grande, near Santarem, where it is often seen coiled up in the corners of farm yards, and is detested for its habit of carrying off poultry, young calves, or whatever animal it can get within reach of.

At Ega, a large Anaconda was once near making a meal of a young lad about ten years of age, belonging to one of my neighbours. The father and son went, as was their custom, a few miles up the Teffe to gather wild fruit, landing on a sloping sandy shore, where the boy was left to mind the canoe whilst the man entered the forest. The beaches of the Teffes form groves of wild guava and myrtle trees, and during most months of the year are partly overflown by the river. Whilst the boy was playing in the water under the shade of these trees, a huge reptile of this species stealthily wound its coils around him, unperceived until it was too late to escape. His cries brought the father quickly to the rescue, who rushed forward, and seizing the Anaconda boldly by the head, tore his jaws asunder…”

A contemporary authority of Anaconda snake is Jesus Antonio Rivas (originally from Venezuela), currently affiliated to New Mexico Highlands University, USA. In a photo presented nearby, from one of his publications, a captured Anaconda can be seen. Rivas and his woman collaborator hold the snake. Rivas also had published note with the title ‘Predatory attacks of green anacondas (Eunectes murinus) on adult human beings’ in Herpetological Natural History (1998; 6: 157-159).

- American political lexicon

The Anaconda word, entered American political lexicon in 1860s! According to a 1963 paper by Professor Theodore Ropp (a military historian at Duke University), the individual responsible for this introduction was Civil War general George Brinton McClellan (1826-1885). Curiously, following the Civil War, Gen McClellan was the Democratic Party rival of Abraham Lincoln in the 1864 Presidential election. He lost to Lincoln in the popular vote by a margin of 10.2% (Lincoln 55.1% vs McClellan 44.9%).

To quote Prof. Ropp’s lines, [dots as well as words in italics and parenthesis are, as in the original.]

“An anaconda is defined in Webster’s new unabridged dictionary as: ‘1: archaic: a python of Ceylon. 2: a large arboreal snake of the boa family of tropical So. America…3: broadly: any large constricting snake.’ The Oxford English Dictionary traces the word to a ‘very large and terrible snake of Ceylon’, which, travelers were warned, could crush a young elephant, thence to a mis-identified South American boa, and finally to ‘all the larger and more powerful snakes.’

The boa also became a neck piece, less expensive than an entire coat for lady killers. The anaconda, according to Mitford N. Mathew’s standard Dictionary of Americanisms, was ‘At the outset of the Civil War, a name given in derision by the radical Union press…to a plan formulated by General [Winfield] Scott for enveloping the South by a cordon of posts on the Mississippi and a sea blockade. Hence the Northern army.”

The inventor of the term is unknown. The present writer, no Civil War buff, has heard it attributed to a Cincinnati newspaper and to General George B. McClellan.

[Anacondas anyone? Military Affairs, 1963; 27 71-76.]

Coda

Considering all the available evidences (zoological, ethnological, etymological, and historical) presented above, the English word anaconda originated from two Tamil adjectival words ‘aanai kondra’ or ‘aanai konda’ Ceylon rock python. On the contrary, its derivation from a Sinhalese word ‘henakandaia’ (a name for brown vine snake, and not a python – that belongs to Colubridae family) by zoology-challenged journalists like Ferguson and lexicographers who followed him is nothing but, in Churchill’s elegant phrase – a terminological inexactitude. NO clerical misidentification occurred in naturalist John Ray’s 1693 description, because Ceylon rock python (now in Pythonidae family) and Anaconda (now in Boidae family) from Brazilian Amazon region, belong to closely related families.

****

I prvovide the two essential references on Ceylon rock snake, cited in the text.

A.F. Abercromby: The Snakes of Ceylon, London: Murray & Co, 1910, pp. 35-39.

Frank Wall: Ophidia Taproanica or the Snakes of Ceylon, Colombo: H.R. Cottle, Government Printer, 1921, pp. 48 – 63.

Oops! A spelling error in the title of Frank Wall’s book. It should be,

‘Ophidia Taprobanica or the SNAKES OF CEYLON’