When the LTTE strangled the Sri Lankan Army’s neck in 2000

by Sachi Sri Kantha, August 18, 2025

Front Note

What happened 25 years ago in Elephant Pass, will NOT be recorded in the history columns of the website of the Government of Sri Lanka’s army. [https://www.army.lk/]. For the benefit of new recruits and the teachers of such new recruits, I provide the following 10 items from my files, culled from the print weeklies of international grade.

If I’m not wrong, an incipient form of the Sri Lankan army’s website became functional in 2000. Until its demise in 2009, the LTTE never operated a website on its own, though a few of the paramilitary Tamil groups such as the Tamil Eelam Liberation Organisation (TELO) and the Eelam Peoples Democratic Party (EPDP) set up and sustained ‘vanity websites’ for fooling the public. Google search engine was officially launched online in Sept 4, 1998. Wikipedia made its entry into the digital world only in Jan 15, 2001. Materials printed in analog format were the primary source of information in 2000. In view of this history, to learn about the battlefront details between the Sri Lankan army and the LTTE in 2000, we need to rely on what had appeared in the print media.

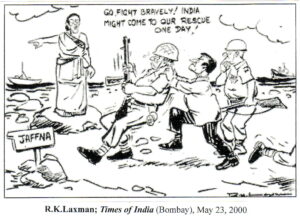

For the vital public record of the Sri Lankan ethnic conflict, in this chapter, I have compiled the materials available in the Economist weekly (9 items, from April to October 2000), below. Caveat: Embellished by a Churchillian colonial heritage of ridiculing non-White natives, Economist’s editorial desk is noted for its anti-LTTE bias. Thus, for a reference (baseline) point, I provide a Time magazine’s weekly report of Nov 17, 1997, first. This is Item 1. While re-reading these brief Economist reports (items 2 to 10) of 2000, it’s still astounding how the LTTE army was able to perform better in the northern battlefield, despite all the constraints it faced in weapon purchase, lack of electricity, negative press and political disadvantage caused by President Clinton administration’s partisan and dubious decision of tagging the ‘Foreign Terrorist Organization’ label on the LTTE, though there was hardly any provocation by LTTE to harm American interests or civilians. More than the shock the LTTE served to politicians in Colombo, what it served to Indian mandarins, defense planners, politicians and journalists in New Delhi was of higher degree. As such, the coverage in the India Today bi-weekly will be assembled for a subsequent chapter. I provide nearby, however, a superb Times of India (May 23, 2000) cartoon of R.K. Laxman, on the retreating Sri Lankan army. Inclusion of a single leg (at the lower right hand corner), running in the indicated opposite direction of Jaffna was a beauty! Also check Laxman’s words in Chandrika’s mouth ‘Go fight bravely! India might come to our rescue one day’.

One more point, I wish to note. That ex-President Chandrika Kumaratunga reaching 80 years recently elicited a few maudlin appreciations for her ‘unfinished job’. But, the reports presented in the Time and Economist indicate Chandrika herself was vile and deceitful in trampling the rights of Tamils. While both her parents – father Solomon Bandaranaike and mother Sirimavo Bandaranaike – were overtly courting the Buddhist loonies from 1950s to 1970s, Chandrika Kumaratunga was tactful in having a pantaloon Tamil politico (Lakshman Kadirgamar) as her foreign minister to propagate her anti-Tamil designs on international platforms.

Item 1

Running Away from The Tigers

Tim McGirk, Time, Nov 17, 1997, pp.24-25

[Note by Sachi: Although my focus is on year 2000, this report published in 1997, provides the background for the Sri Lankan Army’s debacle in Elephant Pass, during May 2000. Tim McGirk was then the New Delhi bureau chief of Time magazine. President Bill Clinton’s State Department had included LTTE [but not al-Quaida!] in the designated list of 13 Foreign Terrorist Organization on Oct 8, 1997. One of the anti-LTTE propaganda ploys at the international podia by the then Chandrika Kumaratunga’s Foreign Minister Lakshman Kadirgamar was the forced, under-age child conscription by LTTE. If so, the question of why the Sri Lankan army had around 23,000 deserters has not been answered. Were they so scared to fight LTTE’s child soldiers?]

Corporal Rana is on the run, a tank gunner, Rana, 2, is one of the Sri Lankan army’s 23, 000 deserters. He fidgets with a lucky amulet hanging around his neck, one that has shielded him in battle against the Tamil Tigers and, more recently, from arrest by military police. He was not the only soldier to go AWOL from his 800-man unit; Rana reckons 300 others slipped away into the jungle or simply never returned from home leave. After serving nine straight months inside a war zone, facing a fanatical enemy who embraces martyrdom on the battlefield, Rana (not his real name) couldn’t take it any longer. Besides, he says, the officers stole his food rations. So during a furlough, Rana ran away. Now he spends his time at his parents’ village home, dodging the police and teasing his hair out into a ‘50s-style quaff. ‘This amulet? A Buddhist monk made it for me before I went away to war,’ says Rana, still fingering the tiny golden cylinder. ‘There’s a prayer inside. t’s supposed to guard me.’

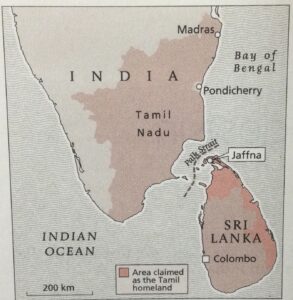

Claimed Tamil homeland (Economist magazine, May 13, 2000, p. 28)

Slender as a flower stem, this talisman is nearly identical to ones worn by the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE), who for the past 14 years have been waging a campaign of guerrilla attacks, assassinations and suicide bombings for their goal of creating a separatist state in the north and northeast of this Indian Ocean island. But the Tigers’ amulet contains not a protective prayer but a lethal dose of cyanide in the event of capture. It is a negative talisman of sorts, and a potent one, asserting the Tigers’ readiness to die for the cause. That shows the difference in attitude between the army and the Tamil rebels toward this grisly conflict that has left more than 50,000 combatants and civilians dead; the soldiers just want to survive, while the Tigers welcome death as a kind of devotional sacrifice. Says Paikiasothy Saravanamuttu, an analyst at the Center for Policy Alternatives, a think-tank in Colombo: ‘The average Sri Lankan doesn’t know what he’s fighting for. It’s an unreal war.’

Such doubts are not shared by the Tigers. The LTTE’s elusive chief, Velupillai Prabhakaran, 43, is not only a genius guerilla tactician but also a deft manipulator of symbols. He has tapped an undercurrent of martyrdom in Tamil folklore and films (his favorite actor is said to be Clint Eastwood) to create an army – mainly of impressionable teenagers, some as young as 11 and 12 – ready to pop cyanide or become suicide bombers for their leader. This fanatical loyalty, senior military officers concede, has enabled Prabhakaran’s 8,000 to 10,000 insurgents to inflict punishing losses on a Sri Lankan army ten times that size.

Prabhakaran’s mesmeric hold over his Tigers may be slipping, though. In a high casualty offensive that began in October 1995, the army seized the northern Jaffna peninsula back from the LTTE. Troops are now pushing to open a supply road through the forests so that Jaffna will no longer be encircled by the Tigers. Battles along the pitted highway have been equally sanguinary for both sides; over the past three months, the army and the LTTE each reported losses of nearly 1,000 men. Neither can afford so many deaths, but it hurts the Tigers more. Explains a Western diplomat: ‘About 500,000 Tamils live up on the Jaffna peninsula, but Prabhakaran is cut off from them now. He’s lost his pool of recruits.’

One sign of Prabhakaran’s growing desperation, say military officers, is that the LTTE warriors sent into battle are getting younger and younger. Recounts Brigadier Sarath Munasinghe, the Defense Ministry spokesman:’ The LTTE attacked one of our outposts, and soldiers could hear a young Tiger girl lying out there in the darkness, wounded. She was in great pain and crying for her mother. Finally, the soldiers couldn’t stand to hear her suffering any longer, so they crawled out and fetched her. The girl had lost a leg. She was 12, maybe.’

In Jaffna, a town dominated by churches, temples and funeral parlors beside a bright lagoon, some Tamils express relief at having been liberated from the austere totalitarianism of the LTTE. In Point Pedro, a group of civil servants and school teachers complain about ‘revolutionary’ taxes and even public executions carried out by the Tigers against dissidents. ‘The LTTE can’t exist without fear’, says a postman who is too afraid of reprisals to give his name. Tiger commandos still wade across the lagoon to murder ‘traitors’.

Many Tamils, though, are just as afraid of the occupying Sri Lankan troops. Authorities concede that in the tumultuous months after the army entered Jaffna, between 300 and 700 Tamils may have ‘disappeared’. These abuses seem to have ended when a new commander, Major General Lionel Balagalle, was put in charge of the western side of the peninsula. ‘Our object is to win over people, and if we’re not careful, then we’ll lose that support’, he says. Sri Lanka’s marked improvement in human right may have helped persuade the US last month, to back President Chandrika Kumaratunga by putting the LTTE on its official terrorist list. (This may hamper the Tigers’ fund-raising among the large Tamil community in the US) ‘Now, on the whole, we don’t hear of such disappearances,’ says the Catholic bishop of Jaffna, Thomas Savunddaranayagam, himself a Tamil. ‘There is still harassment of civilians at checkpoints. But let’s face it, we’re dealing with an army – not saints.’

Even the most hard-line generals doubt that the Tigers can ever be defeated completely. Military spokesman Munasinghe describes the LTTE’s Prabhakaran as ‘a sadist’ and ‘a military maniac’, and concedes: ‘We’re just trying to corner them. If anyone says all the LTTE must be killed, I’d say they’re mad. It’s just not possible.’ Kumaratunga, a motherly figure who was elected on a promise to bring peace to the island’s more than 18 million people (Tamils compose 18%; the majority are Sinhalese), has tried a cease-fire, but it was broken after seven months by the LTTE. She is now attempting to coax Prabhakaran into negotiations by chasing the Tigers out of the towns and into the malarial jungles. At the same time, the President is offering concessions that will make amends for the shabby treatment given the Tamil minority by Sinhalese politicians since independence nearly 50 years ago. She wants the island’s provinces to have semi-autonomy, giving them power over education and taxes, as well as their own police force. But political analyst Saravanamuttu finds this offer ‘unrealistic’. He argues: ‘It should be an asymmetrical devolution’, giving more autonomy to the ‘Tamil provinces than the others’. ‘Otherwise there’s no recognition of the Tamils’ struggle.’

Kumaratunga needs to alter the Sri Lankan constitution to make devolution work. But to do that she must have a two-thirds parliamentary majority, which she is unlikely to get; a strong Sinhalese nationalist lobby is preparing to block her. Diplomats say that her plan is the best formula yet to end the Sri Lankan war, which eats up 27% of government expenditures. ‘There’s an air of Greek tragedy about this, the loss of life and the tremendous toll on the economy’, laments Justice Minister G.L. Peiris. A suspected squad of Tiger commandos recently set off a bomb in Colombo; the blast and ensuing gun battle killed 18 people and damaged two luxury hotels and a newly opened 39-story trade center.

The army is readying for a major assault against Prabhakaran’s jungle bases in Mullaitivu district. But the army, like the Tigers, is running short of men. When only 450 volunteers signed up during a nationwide recruitment drive with a goal of 10,000, authorities tried to lure bac Corporal Rana and the 23,000 other deserters. Several amnesties have been announced – soldiers were given back their full rank and salary – but when the final offer expired on Oct 24, some 10,000 runaways were still missing. Among them was Rana. ‘When I read about the battles, sometimes I feel like going back to my unit,’ he says. ‘My friends tell me it’s better now.’ One improvement they have mentioned: an officer who stole his rations has deserted too. [With reporting by Waruna Karunatilake/Colombo]

*****

Comment by Sachi in 2025

Being a Sri Lankan military spokesman, the comment made by Brigadier Sarath Munasinghe (1949-2008) about Prabhakaran, that the LTTE leader was a ‘sadist’ and a ‘military maniac’ has to be taken with a pinch of salt. The Sri Lankan military itself carries well documented, blemished record in Sri Lanka for Tamil civilian torture, and also in locations like Haiti, where they were engaged in child sexual abuse, from 2004 to 2007.

*****

Item 2

The Worst Defeat

Anon, Economist, April 29th, 2000, pp.26 and 29

Was it all a colossal waste of lives and money? In December 1995, the Sri Lankan army took control of the town of Jaffna from the Tamil Tigers and re-established the writ of the government. Civilian life was restored. more or less. Local elections were held. The army understandably claimed a famous victory. In Colombo, the government of Chandrika Kumaratunga had hopes that the long civil war might at last be coming to an end, and that the Tigers would accept a settlement short of their demand for a separate state for the Tamils in the north-east of the country. Some four years later, on April 22nd, those hopes were in tatters.

The Tigers took control that day of the army base at Elephant Pass army camp, the gateway to the Jaffna peninsula. They are now poised to retake the peninsula and its main town. Their morale is high and their leader, Velupillai Prabhakaran, has conducted their battles with great skill. When the Tigers lost in 1995, Mr Prabhakaran moved his fighters into the jungles to the south of the peninsula. From there they sought to cut all the land routes north. All the time they had their sights on the giant government base at Elephant Pass, manned by two divisions of the Sri Lankan army.

Lieutenant-General Srilal Weerasooriya told journalists this week in Colombo that the Tigers had not overrun the Elephant Pass base. The army had made ‘a tactical withdrawal’. But the army had had to take into account the possibility of the camp being surrounded by the Tigers, he said. He conceded under questioning that the Tigers had a formidable range of weapons, including long-range mortars. The army does not have long-range mortars, a fact that perhaps helped to concentrate the minds of the defenders of the base when they decided to abandon it.

Whatever the general says, the fall of the base is probably the single biggest military loss suffered by the army since the civil war began 18 years ago. Yet army intelligence knew as far back as mid-December that the Tigers were determined to take the base, and presumably passed on this information to the army’s high command. Over the past four months the Tigers have been able to place their weapons within range of the base, apparently without hinderance. What was the top brass doing?

The Tigers launched their offensive against the Elephant Pass camp when there was virtually no government in Sri Lanka. Mrs Kumaratunga, who is defence minister and commander-in-chief, as well as president, left the island in the first week of April to seek medical treatment for an undisclosed ailment and did not return until April 27th. The prime minister, her mother Sirimavo Bandaranaike, suffered a stroke several years ago and remains confined to a wheelchair. Eight government ministers are abroad.

The leader of the opposition, Ranil Wickremesinghe, said this week that Mrs Kumaratunga ‘and some corrupt and inefficient military officials’ must take responsibility for the Elephant Pass debacle. No doubt, but his words are hardly likely to raise the morale of the foot-soldiers of the Sri Lankan army holed up in the Jaffna peninsula. A parliamentary general election has to be held by August. There is little doubt about what one of the big issues will be.

*****

Item 3

Sri Lanka’s Dunkirk

Anon, Economist, May 6th, 2000, p 33

The Jaffna peninsula in northern Sri Lanka resembles a long narrow bottle. The bottle was sealed on April 22nd when Tamil Tiger guerrillas captured the military base at its mouth, a place known as Elephant Pass. This week some 35,000 troops were in the bottle desperate to get out. The only way they could do so was by sea, with perhaps a few going by air. On May 3rd, Sri Lanka’s foreign minister, Lakshman Kadirgamar, said he was considering asking India to help in this Dunkirk-like exercise, for ‘humanitarian’ reasons.

It is a measure of the low morale of the Sri Lankan army that the large number of its men in the peninsula were being chased by not more than a few thousand guerrillas. No doubt someone will have to take the blame for poor leadership, but in their latest action the army chiefs were acting correctly: seeking to save their men for future operations.

The Tigers were reported to be about 37 km (23 miles) from Jaffna town, their former headquarters, which they yielded to the Sri Lankan army in December 1995. They claim a large area of the north and east as the homeland of the Tamils, and seek to make it a separate state. Mr Kadirgamar conceded that Jaffna town might fall, but he added, not very hopefully, that the government would eventually regain it.

Inevitably, there will be calls from the Sinhalese majority for India, the local superpower, to intervene, both to ferry the soldiers to safety and to take on the Tigers. But India sent troops in 1987, aiming to disarm the Tigers, and withdrew in 1990, having suffered heavy losses. It is unlikely that it will want to risk a repetition.

*****

Item 4

The Tamil Tigers close in

Anon, Economist, May 13th, 2000, p 27-28

An unnamed LTTE fighter (Economist magazine, May 13, 2000, p. 27)

In a renewed attack on the Sri Lankan army, the Tigers are threatening the town of Jaffna and sending shockwaves into India.

After a brief lull, the battle of Jaffna has resumed. Sri Lanka’s 17-year civil war exploded again on May 10th when the Tamil Tigers launched a major offensive against the government’s forces. The Tigers attacked military units based in villages on the outskirts of Jaffna town, the prospective capital of the Tamil state for which they are fighting. On their own radio station, they warned the town’s residents to move to safe places. With 5,000 or so fighters, including women and children, the Tigers are greatly outnumbered by the government’s 35,000 or more troops. But the Tigers are fearsome guerrillas and the Sri Lankan army is demoralized, badly trained and under-equipped. Few people in Colombo, Sri Lanka’s capital, expect the army will be able to hold on to Jaffna. It may not even keep the local air and sea ports, which it held before capturing Jaffna from the Tigers in 1995. The government would then, for the first time, lose its foothold on the Jaffna peninsula. The rumble of a country about to break up would rock not just Colombo but also Delhi, India’s capital.

It may not come to that. The Sri Lankan army could pull itself together. The Tigers’ leader, Velupillai Prabhakaran, will no doubt be tempted to declare independence if he takes Jaffna, but he may think better of it. The Tigers, he knows, are reviled internationally as terrorists; an upstart Tamil state would win virtually no international recognition. Nonetheless, the government’s recent reversals have stifled a nascent peace process nurtured by Norway and undermined a search for consensus on the Tamil issue between Sri Lanka’s main political parties.

Colombo is calm, but grim. Last week the government published a 200-page public security act, which imposes blanket censorship and allows the authorities to prohibit demonstrations and confiscate property. Newspapers have taken to publishing white spaces where the censors have mauled their articles. Taxes on cigarettes and alcohol were increased this week to help pay for the military campaign. Sri Lanka, the government has declared, is now on a ‘war footing’.

Fighting resumed after Sri Lanka’s president, Chandrika Kumaratunga, rejected an offer by the Tigers of a ceasefire leading to negotiations. She could not afford to accept it, as it entailed surrendering the Jaffna peninsula without a fight. Her defiance does not necessarily improve her position.

Before the Tigers launched their latest offensive in April, overrunning Elephant Pass, the link between the peninsula and the rest of Sri Lanka, prospects for a settlement were brightening. Mrs Kumaratunga had survived an assassination attempt, presumably by the Tigers, and had been re-elected in December. Her anger seemed to be mellowing into statesmanship. She began talks with the main opposition leader, Ranil Wickremesinghe, on what sort of autonomy could be offered to the north and east of the country, the area claimed as the Tamil homeland. The idea was to forge a broad agreement within Sri Lanka’s Sinhalese majority, without which no offer to the Tigers would stick. At the same time, Mrs Kumaratunge and Mr Prabhakaran agreed to Norwegian ‘facilitation’, which in time might have lead to direct negotiations.

None of that is in prospect now. Citing the crisis, Mrs Kumaratunga has withdrawn from the talks with the opposition party, though they have not been formally broken off. A Norwegian delegation was expected to discuss the crisis with the Indian government in Delhi on May 11th, and it may proceed to Colombo after that. But, says a western diplomat, ‘the prospects of meaningful discussions at this stage are very, very poor.’

Fears of Backlash

It is unclear how much political pressure Mrs Kumaratunga will face to stiffen her line against the Tigers. A parliamentary election is due by October at the latest, which may make it difficult for her to be generous, especially in the face of a military defeat. A new party, Sihala Urumaya (Sinhalese Heritage), has been formed to rally nationalists opposed to compromise with the Tigers. It does not count for much now, but could count for more if Jaffna fell. There is some fear that the Tamils in the south, who are thought to outnumber those in the north and the east, will be attacked. One reason the government gave itself extra powers was no doubt to forestall such chaos breaking out in the south.

Jehan Perera, the media director of the independent National Peace Council, argues that in some respects the present crisis has improved the chances of peace. The Tigers hae been discredited, even among some Tamils, by making war on the eve of peace talks, he believes. And Sri Lankans of all persuasions are now willing to accept international mediation, a prerequisite for a negotiated solution. More than 55,000 people have already been killed in the fighting. No reasonable person wants to see part of Sri Lanka ruled by a force that knows everything about killing and nothing about governing.

Least of all does India, Sri Lanka’s giant neighbour. India has its own separatist worries, especially in the northern Muslim-majority state of Kashmir. It does not want borders in its neighbourhood redrawn along ethnic lines. The Indian government regards Mr Prabhakaran’s rise with horror. A battle for Jaffna could send refugees across the Palk Strait to Tamil Nadu, an Indian state with a much bigger Tamil population than Sri Lanka’s. Victory in Jaffna could lead to greater Tiger infiltration of Tamil Nadu and the stirring of latent separatism there.

India has strong reasons to back Mrs Kumaratunga’s efforts to keep Sri Lanka whole, but equally strong reasons to be wary. An Indian peacekeeping force in the 1980s antagonized both sides and pulled out after losing 1,000 men. The government is also loth to anger Indian Tamils and their political parties, some of which are part of the ruling coalition, by backing the Sri Lankan government too strongly. India’s prime minister, Atal Behari Vajpayee, has so far dodged Sri Lanka’s reuests for help in evacuating its troops from Jaffna and said no to military assistance. India’s government and opposition parties have agreed that Sri Lanka should remain whole and that its minorities should be protected. India offered to mediate if asked by both sides.

That balance will be hard to maintain if Mr Prabhakaran conquers Jaffna and evicts the government’s forces from the peninsula; even harder if he proclaims a state there. But saying it will not make it so. The Sri Lankan army still controls, at least by day the main citie claimed by the Tigers in the east. With better connections to the rest of the island, they will not be easily overrun. Indeed, if the army leaves the Jaffna peninsula, its hold on the east could tighten. No matter how stunning their victories, the Tigers will eventually have to come to the negotiating table.

*****

Item 5

Another Bomb in the War

Anon, Economist, June 10th, 2000, p 27

It was ‘War Heroes Day’ in Sri Lanka. The president, Chandrika Kumaratunga decided that on June 7th the country should salute its soldiers who are suddenly doing rather better in their fight against the Tamil Tigers, the guerrilla group seeking a separate state in the north and east of the country. Temple and church bells would ring out, after which everyone would stop work for two minutes. It was a measure of Mrs Kumaratunga’s growing unpopularity that the ceremony was largely ignored. Life went on as usual in most of the country.

One of the few to observe the ceremony was C.V. Gunaratne, the minister for industrial development. He was at the head of a procession from his own constituency of Ratmalana, a suburb of Colombo. It did not go far. A bomb exploded, killing Mr Gunaratne and 21 others.

Who set off the bomb is unclear. The police say it was the work of a suicide bomber. Ministers say the bomber was a Tamil Tiger, since the Tigers have used suicide bombers in previous attacks in the capital. As on such occasions in the past, the Tigers have remained silent. In suspicious-minded Colombo, not everyone is prepared to believe that the Tigers are the only killers in a country where political assassination has become a way of life. But if the Tigers were not responsible, who might have killed Mr Gunaratne in his own stronghold?

Mr Gunaratne was one of the few ministers whose loyalty to Mrs Kumaratunga was beyond question. It was widely believed that he would seeon be made prime minister, replacing the ailing 84 year-old Sirimavo Bandaranaike, the president’s mother. Mr Gunaratne would have had plenty of enemies.

Mrs Kumaratunga has twice been elected president, most recently in December, on a promise to end the civil war. The political seers believe that her People’s Alliance government will be defeated in the parliamentary election due by August. Apart from her failure as a peacemaker, her cabinet is divided and stories, true or not, are circulating of graft in the government.

Her best hope of winning in August is the voters will be grateful for a turning point in the long war against the Tigers, if that is what the country has reached. Such reliable news as comes from the battlefront suggest that the army is no longer in retreat from the Tigers. The town of Jaffna is being successfully defended. Instead of talk about the army being evacuated from the area, optimists now say the Tigers will be driven back to the jungle.

The army’s successes in the north are largely due to assistance provided by Israel. It has provided arms of a quality to match the Tigers’. Some reports say that Israeli officers are now helping to direct the army’s operations. To pay for the arms, Sri Lanka is digging even deeper into its pockets to increase defence spending.

The political cost may be more difficult to assess. Israel now has full diplomatic ties with Sri Lanka for the first time, which will not go down well with the Islamist lobby in Colombo. Moreover, though someone appears to have put backbone into Sri Lanka’s previously demoralized troops, it was evidently not the generals. Pushed aside by the Isarelis, they may feel almost as aggrieved as the Tigers.

*****

Item 6

The Growing Cost of War

Anon, Economist, July 13th, 2000.

The Tigers are being held in check, but at a price.

During the 17 years of Sri Lanka’s civil war, neither the government nor the Tamil Tiger rebels have lacked the money to pay for the weapons to go on fighting. The Tigers are kept going mainly by groups of sympathisers in Europe, North America and India. Jut how much money they have raised is guesswork, but it must amount to many millions of dollars, since the Tigers have plenty of modern weapons, a small navy and a number of aircraft. The government’s defence costs are published. Although the war remains affordable, at least in financial terms, there are signs of strains in the economy as a result of a surge in the fighting in recent months.

At the time of the most recent budget, in February, there was little fighting in the north and east of the island, where the Tigers claim a homeland. A sum equivalent to $730m was earmarked for defence. Fighting flared up in April, when a key government position at Elephant Pass, the gateway to the Jaffna peninsula, fell to the Tigers. This was judged to be the worst defeat suffered by the army in the war, and put down to inadequate weapons and poor leadership.

Sri Lanka turned to Israel for military help. Full diplomatic ties were swiftly established, and Israeli military advisors and weapons arrived in Colombo. The Tigers now face a well-equipped army. Morale is said to be high. The command structure has improved. That is the outcome of the Israeli connection. But it must be paid for.

After the Israeli came on the scene, $150m was added to the defence estimates, bringing the total to $880m. Some defence expenditure is hidden in other parts of the budget. Allowing for overspending, a realistic figure for the current year would be in the region of $1 billion. This is a little over 6% of the GDP forecast for this year, about the average for most developing countries, but higher than last year.

Part of these war costs will be recouped through a national security levey, a tax on a wide range of goods and services. It currently meets about a third of the bill for the war; the balance is covered largely by government borrowing and the effects of inflation. To stop the drain on Sri Lanka’s foreign currency reserves, the government has made imports dearer. Paraffin, diesel oil and cooking gas all cost more. The Sri Lankan rupee has been devalued by nearly 5%. The government is also concerned by the size of the country’s underground economy, which N.U. Jayawardena, a former governor of the Central Bank, estimates to be worth about $3 billion a year.

A drifting economy is not the ideal basis for a government facing general election. Under the constitution, the life of Sri Lanka’s current parliament comes to an end in August and an election must be called by mid October at the latest. The president, Chandrika Kumaratunga, is not up for re-election, but she will be hoping that her People’s Alliance coalition will hold on to power in parliament. The better news from the battlefront may help her supporters. The Tigers appear to be short of recruits to replace the increasing number of their fighters killed in action. A report by a non-government group this week said the Tigers are conscripting children as young as 13. The government has long accused the Tigers of recruiting children. This week’s report may be considered less partial: it comes from the Jaffna-based University Teachers for Human Rights, most of whose members are Tamils who used to teach at Jaffna University.

Still, the peace Mrs Kumaratunga has promised continues to elude her. Draft proposals for the devolution of Tamil lands were coolly received by two Tamil parties in parliament this week. Neither party supports the Tigers, but both say, no doubt correctly, that the proposals fall far short of the Tigers’ minimum demands for a gurantee of the ‘integrity of Tamil-speaking territory’.

Mrs Kumaratunga might be tempted to try to put off the general election by extra-constitutional means, perhaps arguing that an election now would be divisive. But it would be a dangerous course for the president to take. The army is an independent centre of power in Sri Lanka. So is the island’s Supreme Court. They would be quick to defend the constitution.

*****

Item 7

Sri Lanka Backs Away from Devolution

Anon, Economist, August 12th, 2000, p. 24

It seemed doomed from the start. Now Chandrika Kumaratunga, Sri Lanka’s president, faces an uncertain political future after she was obliged this week to abandon a constitutional-reform bill aimed at ending the country’s long and brutal war with the Tamil Tigers.

The bill would have given Sri Lanka a federal system of government, allowing the Tamils in the north a high degree of autonomy over their claimed homeland. It was, claimed Mrs Kumaratunga, the best hope for a lasting peace in a war in which 60,000 people have died. But faced with growing hostility towards the bill, including street protests led by Buddhist monks, she came to realise that her party would be unable to muster the necessary two-thirds majority in Parliament. Rather than face defeat, Mrs Kumaratunga decided to postpone the vote indefinitely.

The bill would have devolved considerable power to regional councils, which were to be elected by seven of Sri Lanka’s nine provinces. For the northern and eastern provinces, which cover the areas being fought over by the Tigers, a special ten year interim arrangement would have allowed the president to nominate council members from recognized political parties. Many of her opponents claimed this was just subterfuge and that the real purpose of the bill was to partition the country. As for the Tigers, their leaders had rejected the plan They want nothing short of independence.

What so enraged the Sinhalese, who are mostly Buddhists and make up the majority of Sri Lanka’s population, was that the reforms seemed no longer to make it a duty of the state to protect and foster Buddhism. The country’s 30,000-plus Buddhist monks are a powerful lot and they threatened to do everything in their power to stop the bill.

An additional problem for the government was that its slender majority obliged it to rely on defectors from the opposition to provide the necessary two-thirds votes. Though it was said that potential defectors were being lured with cash, they did not seem to be forthcoming. Even if there had been enough, and the bill had passed, the reforms would still have had to be approved in a referendum.

Mrs Kumaratunga, who was re-elected last December, was in a rush to ram the bill through the Parliament before its dissolution on August 24th. An election should be held by mid-October. But Mrs Kumaratunga is facing growing unpopularity not only because of the war but also because of the faultering economy. A further sign of her troubles came on August 10th when her 84 year-old mother Sirimavo Bandaranaike, resigned from the largely ceremonial post of prime minister. She was replaced by Ratnasiri Wickremanayake, the minister of home affairs. As he played a leading role in forcing the government to abandon the constitutional reforms, many saw the appointment as a further sign of a split in the ruling party.

*****

Item 8

Blood before the Ballot

Anon, Economist, Sept 9th, 2000, p. 34 – 35

Well before the general election on October 10th, the political temperature in Sri Lanka is rising dramatically. As the president, Chandrika Kumaratunga, battles to keep intact her ruling People’s Alliance, squabbles have turned to bloodshed. Four members of opposition parties have already been murdered.

Mrs Kumaratunga has herself taken a battering, albeit only metaphorically. Last month she failed to ram through Parliament a new federal constitution which would have given more power to the regions. This was designed to bring to an end the long war with the Tamil Tiger separatists in the north of the country. But the president backed down and abandoned the bill because of growing hostility to it among Sinhalese, who make up three-quarters of the population. In the ensuing melee, Mrs Kumaratunga sacked her mother, the ailing Sirimavo Bandaranaike, as prime minister, giving the job to Ratnasiri Wickremanayake, the home minister.

The ruling party looks increasingly fractious. One of its allies, the Sri Lanka Muslim Congress, threatened to go it alone but then decided it would return to the fold. Anohter, the Indian Workers’ Congress, has split, with one wing aligning itself with the opposition United National Party (UNP).

Now much of the ruling party’s core Sinhalese base seems to be lining up behind Mr Wickremanayake, and he has the backing of the country’s powerful Buddhist monks. He told senior Buddhist leaders that as far as the government was concerned, the ‘devolution package’ had died with the dissolution of Parliament. He also assured the monks that the government would not talk to the Tigers, who he said ‘must be laid to rest before a solution to the ethnic problem could be looked at’. Mrs Kumaratunga sings a different tune. She told a television audience she would bring the proposals back to Parliament, after she wins the general election.

The economy is drifting, with a growing trade deficit, dwindling reserves and total foreign debt at the end of June standing at $6.8 billion, or roughly half the GDP forecast for the year. Inflation is rampant, the currency unstable, and foreign investors are shunning the Colombo stockmarket. Opposition politicians have accused some members of the government of corruption. Most of their charges relate to kickbacks alleged to have been made during the sale of state assets by the government over the past six years. None of this has enhanced Mrs Kumaratunga’s reputation for personal integrity.

Apart from preserving the unity of her own party, the president will be facing an onslaught on many fronts. By the time nominations for the election closed on September 4th, a total of 29 parties had thrown their hat into the ring. This suggests growing dissatisfaction with the two main parties: Mrs Kumaratunga’s People’s Alliance and the UNP. Many people are becoming tired of the leadership of both the main parties, controlled, in their eyes, by two families that have held power too long.

That view has been reinforced by the continued feuding of their leadership. Mrs Kumaratunga has accused Ranil Wickremesinghe, the leader of the UNP, of knowing in advance about an attack by a suicide bomber on one of her political rallies during the presidential election in December last year. In that attack, which the government blamed on the Tigers, several people were killed and Mrs Kumaratunga lost an eye. The allegation was described as ‘ludicruous’ and ‘wicked’ by Mrs Kumaratunga’s estranged brother, who campaigns for the other side. With such infighting, Sri Lanka’s election could turn into an even more dangerous affair.

*****

Item 9

The War the World is Missing

Anon, Economist, Oct 7th, 2000, p. 23 – 24 and 26

The Tamil Tigers’ struggle in Sri Lanka is one of the longest-running wars. But as the island prepares to go to the polls, both sides are losing interest in suing for peace.

Even by the standards of divided countries, Sri Lanka seems to be two different places. Most of the island is a lush land of palm-fringed beaches, tea gardens and pop-music radio stations that sound as if they are being beamed from New Jersey. The insurrection by the island’s Tamil minority, which has claimed 60,000 lives and is dragging on into its 18th year, seems relevant only from time to time. Even bombs in the capital, Colombo, have the far-away quality of motorway accidents.

Not so in Trincomalee on the east coast. There, checkpoints are thicker on the ground than traffic lights. Although the army controls the town, there are ‘uncleared’ areas barely 32 km (20 miles) away in the hands of the dreaded separatist army, the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam. From these areas the Tigers can strike inside inside ‘cleared’ Trincomalee. On October 2nd a suicide bomber, presumably one of theirs, killed 21 people, including a candidate aligned to the ruling party, at a rally near the town for next week’s election. Such operations have the virtue, from the Tigers’ point of view, of stirring a cocktail of overreaction and discrimination by the authorities that, in turn, feeds separatism among the local Tamils.

A visiting journalist hears a torrent of grievance. There are complaints about cordon-and-search operations by the security forces; there are tales of beatings, murder and reprisal. A woman says that the security forces murdered her brother, then refused to release his body unless she signed a statement saying he had belonged to the Tigers. She refused. The fishermen of Pattanatheru, a village nearby, lament security restrictions on where they can fish and their debts to Sinhalese mudalalis (proprietors), whom they repay by turning over their catch at cut-rate prices. Banks will lend money to fishermen from the Sinhalese majority, but not to them, they say.

Sri Lanka’s government claims that there is scant support among ordinary Tamils for the Tigers, who are a vicious terrorist group as well as an astoundingly successful army. But although the Sri Lankan army has become somewhat less brutal, it has not improved enough and the police are less reformed. For that reason, the Tamils of Trincomalee seem to regard the Tigers as their defenders. ‘It is because of them that we are surviving’, says one young Tamil.

The prospects for narrowing the divide look dim. Sri Lanka is scheduled to hold a parliamentary election on October 10th. It is likely either to prolong the current set up, a government obedient to the president, Chandrika Bandaranaike Kumaratunga, who was re-elected to a six year term in December 1999, or to produce gridlock: a parliament without an overall majority or one dominated by the opposition United National Party (UNP). Although the two main parties offer contrasting proposals for settling the conflict, there is little expectation that either will bring peace.

Why peace eludes Sri Lanka is something of a puzzle. Compared with the Arab-Israeli dispute or the struggle over Kashmir between India and Pakistan, the obstacles seem small. Hardliners do not have much parliamentary clout in Sri Lanka. The two biggest political parties, though they disagree over detail, both say they will talk about any compromise, short of granting the Tamils an independent state. In contrast with the insurgents in Kashmir, who are backed by Pakistan, the Tigers have no outside state behind them. Unlike India, Sri Lanka has accepted international involvement in its dispute: a Norwegian envoy is conveying messages between the antagonists. Nor is there ethnic rancor of the sort that has frustrated peace in the Balkans. Sinhalese and Tamils seem able, by and large, to forgive each other for the excesses of their leaders.

So why is nobody dusting off the Nobel peace prize? The answer lies in two finely-poised struggles: for political mastery in Colombo and, more important, for military mastery in the north-east, the Tamils’ prospective homeland. The first has frustrated a consensus between the UNP and the ruling People’s Alliance on what sort of offer the government should make to the Tamils, who are about 13% of the population. Mrs Kumaratunga presented her ideas to parliament as a draft constitution that would have developed some powers of the highly centralized state to the regions, including the north-east. She withdrew it in August, when it emerged that Ranil Wickremesinghe, the UNP’s leader, would not support it. The mutual loathing between president and opposition leader has little to do with principle.

Whether the flailing about in Colombo will achieve anything depends on another protagonist, Velupillai Prabhakaran, the Tigers’ leader. Mr Prabhakaran’s ambition is to set up Eelam, a soverign Tamil homeland. With an armed force of 7,000 – 8,000 he has captured, the Tigers claim, 70% of Eelam (though a far smaller share of its population), from an army ten times the size.

In Colombo it is said that he tells new recruits that they have the right to kill him if he settles for anything short of Eelam. His followers are thought to have murdered many Tamils less fanatical than he is, along with leaders who have dared to negotiate with him, including an Indian prime minister and a Sri Lankan president. Mrs Kumaratunga has little reason to love a man who was presumably behind the bomb that nearly killed her during the last presidential campaign. They and the opposition leader form a Bermuda Triangle of hatred and suspicion in which peace efforts have so far disappeared.

The economic damage

It is a Sri Lankan cliché to observe that the Sinhalese majority has many of the complexes of a minority. One reason is that, although they outnumber Tamils in Sri Lanka, they are outnumbered by Tamils just across the Palk Strait in the Indian state of Tamil Nadu. There is thus a sense that the Sinhalese language and Buddhism, the religion of most people who speak it, is under threat from a Tamil juggernaut with a beachhead in Sri Lanka. A second reason is that the British who ruled Sri Lanka until 1948, treated Tamils, especially those of the Jaffna peninsula, as an elite. They were Sri Lanka’s best educated people and got more than their fair share of plum government jobs.

Soon after independence, the Sinhalese began to claim what they regarded as the majority’s rightful place in Ceylon, as it then was. The then prime minister, S.W.R.D. Bandaranaike, Mrs Kumaratunga’s father, championed a policy of making Sinhalese the country’s sole official language and Buddhism the state religion. Tamils found themselves on the wrong end of racial preference policies in favour of Sinhalese and Muslim applicants to universities. These disabilities, coupled with unemployment among the young provoked violence in the Tamil majority Jaffna peninsula, and horrific counterviolence in the Sinhalese south in 1983. Separatism and war have raged since.

This has cost Sri Lanka dear. It was, and in many ways remains, a model developing economy with rates of literacy, fertility and life expectancy closer to those of Europe than to those of other South Asian countries. It was the first economy in the region to liberalise, in 1977. Despite the shocks of war, the economy grew at a respectable average rate of 4.7% between 1980 and 1999. This year GDP is expected to grow by 5.5½%.

Yet it could have been so much better.Saman Kelegama, head of the Institute of Policy Studies in Colombo, guesses that forgone investment, lost tourism, military spending, the loss of workers to death and emigration and other costs of the war amount to 200% of 1999’s GDP. In a Sri Lanka at peace, the economy could grow at an average annual rate of 8%, thus absorbing the 140,000 people who enter the workforce each year. Unemployment – among both Sinhalese and Tamil young people – has been a primary cause of Sri Lanka’s bloodshed. Young men (and women) from country villages join one army or the other for lack of anything else to do. An estimated 700,000 people have left for southern Sri Lanka or abroad, where they have become a mainstay of the Tigers’ finances. A similar number are displaced from their homes in and near the north-east by shifting lines of battle.

The ferocity of war masks progress both in policy and in Sinhalese thinking about the conflict. No longer does a crude majoritarianism prevail. Sinhalese has lost its privileged status in the constitution, if not always in day-to-day life. Sri Lanka recognized Tamil as an official language. The Tamils’ handicap in getting university places is largely gone. What remains is their resentment and insecurity, which can be mollified only by giving them political autonomy.

What price devolution?

At the moment, there is no autonomy for the north-east except where the Tigers rule. But the main political parties now express few inhibitions about devolving powers to the regions. The foreign minister, Lakshman Kadirgamar, says the government wants a solution ‘on federal lines’, using a word that was, and in Sinhalese nationalist circles still is, taboo. The government’s strategy is to placate moderate Tamils and pummel Tigers into accepting a deal.

Unfortunately, Mrs Kumaratunga’s ideas for constitutional reform meshed with no one else’s. They offered too little devolution to satisfy even non-Tiger Tamils, but enough to antagonize Sinhalese nationalists and many of the Buddhist clergy, who want no weakening of the unitary state. One function of the election will be to test how much support nationalists can muster at the ballot box.

Nor is devolution in itself a magic answer. A permanent merger of the Northern and Eastern Provinces, for example, is something most Tamils would insist on The president’s constitutional draft wriggles out of this by subjecting a merger of the provinces to a referendum in the eastern portion after ten years. This ridiculous-sounding fudge is a response to a serious problem. Although the north is almost entirely Tamil, the east has big populations of Sinhalese and Muslims, most of whom speak Tamil but see themselves as a separate ethnic group and have often allied with the Sinhalese. They might vote to secede from the northern province. Trincomalee is almost evenly divided among the three groups. Although professing love for their neighbours, the native Tamils point out that, in the 1881 census, the district’s population was just 4% Sinhalese. Colonisation by chauvinist governments brought their share of the population to 34% a century later. Their fate would be uncertain in a Tamil-run, and especially a Tiger run, north-east.

Mrs Kumaratunga means to reintroduce her constitutional draft, or a modified version, to the new parliament. It will make little difference. The People’s Alliance is unlikely to win the two-thirds majority required to pass it. The president has threatened to turn parliament into a constitutional assembly, which could pass the new constitution by majority vote. Sri Lanka’s constitution authorizes her to do no such thing. Mahinda Samarasinghe, an influential opposition MP, wans of ‘3.6m people taking to the roads’ if she tries. Nor would it impress the Tigers, who say the devolution of package ‘fails to address the key demands or the national aspirations of the Tamil people.’

Some people think the UNP’s more accommodating line – an offer of an ‘interim council’ to run the north-east with a leading role for the Tigers while a final solution is worked out – has a better chance of ending hostilities. That presumes that the Tigers will be less bloody-minded, and simply less bloody, than they have ever been before. Even if he becomes prime minister after the election, Mr Wickremesinghe will have a hard time persuading the president of that.

In the Tigers’ lair

Would any solution acceptable to most Sinhalese and Muslims also satisfy Mr Prabhakaran? In theory, possibly. The Tigers are committed to the ‘Thimpu principles’, among them the Tamils’ right to self determination and to a homeland with territorial sovereignty. Most Sri Lankans, the government included, regard these as tantamount to secession; but some, such as Rohan Edirisinha, a leading constitutional lawyer, think they may be compatible with belonging to a Sri Lankan federation. The Tigers have hinted that they think so, too. In rejecting Mrs Kumaratunga’s proposals, Anton Balasingham, the Tigers’ ‘theoretician’, seemed to back ‘radical structural reforms’ to the Sri Lankan constitution, implying that there could be room for Eelams within it.

What prevents compromise, apart from Mr Prabhakaran’s fanaticism, is what might be called a dynamic stalemate between the two armies. That is the results of the Tigers’ astounding potency and the Sri Lankan army’s refusal to lose decisively.

Since 1987, when India unwisely intervened to keep a ‘peace’, the Tigers have evolved from a band of 1,000 – 2,000 cadres into a force of 7,000 capable of operating ‘at all five spectra of conflict’, according to a military analyst. They have a field army equivalent to three brigades, armed with artillery, armour, radios with encryption devices and other paraphernalia, which now fights on the Jaffna peninsula. They have a 1,000 – cadre guerrilla force in the Eastern Province, which specializes in ambushes and mortar attacks. They have a terrorist outfit, which sends suicide bombers to Colombo and blows up electricity transformers. They have a global propaganda network of websites, broadcasters and newspapers, and a diplomatic wing. All this is paid for with contributions, mostly from expatriate Tamils, and profits from businesses, such as restaurants and shipping. The government guesses that the Tigers take in $80m a year.

In 1995 the Tigers lost the city of Jaffna, the main town of the peninsula, to the Sri Lankan army after talks with Mrs Kumaratunga broke down. Since then they have had a string of success, gaining swathes of territory in the north, in April overrunning Elephant Pass, the disused but heavily defended land link between the peninsula and the rest of the island, and then very nearly recapturing Jaffna, which might have prompted a declaration of independence.

What the Tigers ‘liberate’, they rule. The apparatus of the Sri Lankan state remains, but it takes orders from and is supplemented by the Tigers. People familiar with the uncleared areas (and well disposed to the Tigers) talk of them almost as Tamil havens. The Tigers, they say, ,make sure that teachers show up to teach at state schools, and pay them to give extra lessons. Mr Prabhakaran himself is said to set demanding standards for the number of students who must pass state exams. The government sends in food and supplies (too little, complain the Tamils); the Tigers supervise their distribution. Villages have boxes into which Tamils can post petitions and suggestions, which they say go directly to Mr Prabhakaran. To them he is Talaivar, the leader.

Yet there are credible reports that the Tigers can be as brutal to their own people as they are to their enemies. Amnesty International, a human rights group, said last year that the Tigers have ‘recruited children as combatants on a large scale’, sometimes forcibly. Neutral observers say the Tigers have also shelled Tamil civilians during their offensives, as has the Sri Lankan army. The lack of provisions in the uncleared areas is partly the Tigers’ fault, claims the government; they commandeer the lorries for weeks at a time, disrupting supplies. The Tigers know that grumbling about provisions is likely to be directed at Colombo.

The army fights back

After nearly losing Jaffna, and with an election looming, Mrs Kumaratunga pulled the armed forces together. She spent about %350m on new weaponry, including devastating multi-barrel locket launchers and MiG-27 fighter bombers, and established a joint-operations headquarters, which brings all armed forces, including the police, under a single command. In September the army began to make some progress, notably with the recapture of the peninsula’s second-biggest town, Chavakachcheri, a deserted pile of rubble by the time the soldiers moved in.

Sri Lanka’s demoralized army (a fifth of its troops have deserted) is feeling stirrings of hope, and the government is optimistic that a series of reversals will squeeze the Tigers’ morale and money. Mr Kadirgamar, the foreign minister, says that the flow of money to the Tigers ebbs when they suffer defeats. In April and May they ‘went around Europe saying Eelam is around the corner’. The army’s recent victories have quietened that boast. Sri Lanka and India stepped up their cooperation, says Mr Kadirgamar, tightening a ‘naval cordon’ that is reducing the flow of arms to the Tigers.

The government thinks that only a series of defeats will persuade Mr Prabhakaran to negotiate for something less than full independence. It has yet to break his spirit. The Tigers this week launched the fourth phase of their ‘Unceasing Waves’ offensive, which may be intended to fulfil their pledge to recapture Jaffna this year. The battle for the peninsula may be coming to a head.

Meanwhile, says Mr Kadirgamar, ‘not much is happening’ with Norway’s efforts at mediation. The Tigers have made it clear that they have ‘no interest in talking about peace’. For the moment, that goes for both sides: both the government and the Tigers believe they have more to gain from war.

*****

Item 10

A Double-barrelled Verdict

Anon, Economist, Oct 14th, 2000, p. 38 – 39

This week’s election will probably encourage President Kumaratunga to press ahead with devolution, while still fighting the Tamil separatists.

Election day, October 10th, was a gloomy one in Sri Lanka. Sirimavo Bandaranaike, who in the 1960s became the world’s first woman to be elected prime minister, died of a heart attack after voting, presumably for the party led by her daughter, the president. Perhaps, half-a-dozen people died more violently, bringing the death toll for the parliamentary campaign to more than 70. Rival monitoring groups disagreed about the extent of the vote rigging, intimidation and other malpractices, but agreed that they were widespread and mostly the fault of the ruling People’s Alliance. In some places, its candidates apparently went after rivals in the same party. The election commissioner delayed announcing final results while he consulted the parties about the fraud allegations.

The result looks unlikely to advance a settlement of Sri Lanka’s 17-year war against the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam, who want a separate state in the north-east for the Tamil minority. The People’s Alliance of President Chandrika Kumaratunga, whose job was not at stake, remains the largest grouping, though its share of the 225-seat parliament has apparently shrunk slightly. It seems to be in a position to cobble together a working majority similar to- though weaker than – the one it had in the last parliament. The Eelam People’s Democratic Party, a moderate Tamil group that backed the government but was not part of it in the last parliament, has apparently won just enough seats to give the People’s Alliance a bare majority. A once-friendly Muslim party, which has charged the People’s Alliance with electoral fraud, might be persuaded to return to the fold.

Mrs Kumaratunga is thus likely to persevere with her double-barrelled strategy for dealing with the civil war: wooing moderate Tamils by devolving powers to the regions while trying to defeat the Tigers on the battle field. Right-wing nationalist parties, which regarded the devolution plan as an affront to the Sinhalese majority, were trounced in the election. The result was a ‘clear Sinhalese mandate for the dual-track policy’, says Dayan Jayatilleka, a political analyst.

The main opposition party, the United National Party (UNP), still harbours hopes of fashioning a government from parliament’s fractious arithmetic. It favours negotiations with the extremist Tigers. Some of the Tamil parties it would depend on are partially under the Tigers’ sway. But the chances of a peacenik government led by the UNP look slim. The JVP, a Marxist party that has emerged as the third largest parliamentary force, has horrid memories of earlier UNP governments, which repressed it brutally during the 1980s, when it was a violent left-wing insurgency of Sinhalese youth.

Some commentators think the humbling of both main parties will have a salutary effect. Devolution could become easier. Faced with five years in opposition, the UNP might assent to a modified version of the constitutional package that it rejected before the election. Since the package requires a two-thirds majority, Mrs Kumaratunga needs the UNP’s votes. As president, she has powers of patronage to tempt all but the most steadfastly hostile MPs.

But her shaky majority, if she manages to put one together, could boost the influence of Tamil parties sympathetic to the Tigers. They could press the president to make her devolution offer more generous to Tamils and to look harder for opportunities to negotiate with the Tigers. On the other hand, the newly-important JVP is an implacable foe of devolution, and resists even the unamended package, let alone one designed to bring the Tamil parties on board.

Sri Lanka’s voters have thus produced a parliamentary muddle that allows for plenty of deal-making among the parties. Their leaders are gathering for Mrs Bandaranaike’s funeral, set for October 14th. Mourning may take a back seat to manoueuvring.

Coda

In 2000, LTTE’s hand in the battle front reached the zenith, against the demoralized Sri Lankan army. Only the military assistance from Israel (courtesy, with Uncle Sam’s blessings), Sri Lankan army was able to block the fall of Jaffna. Chandrika Kumaratunga, was largely unpopular even among Sinhala electorate, and she had to postpone a constitutional-reform bill indefinitely due to threat of 30,000 odd Buddhist monk lobby. Thus, history repeated itself, when her father Solomon Dias Bandaranaike also abandoned the Bandaranaike – Chelvanayagam Pact (of July 26, 1957) in May 1958, mainly due to threat from the yellow-robed Monks.

The two sentences in the Economist’s commentary of October 7th 2000 about Tamil collaborator Lakshman Kadirgamar’s deceitful deal-making exercise, deserves notice.

“The foreign minister, Lakshman Kadirgamar, says the government wants a solution ‘on federal lines’, using a word that was, and in Sinhalese nationalist circles still is, taboo.

The government’s strategy is to placate moderate Tamils and pummel Tigers into accepting a deal.”

In my view, the Economist analyst had missed emphasizing the point. Mr Kadirgamar pouting ‘federal lines’ was a ‘Chandrika-deception’ ONLY meant for consumption and approval in New Delhi and Washington DC.

The description of Douglas Devananda’s “The Eelam People’s Democratic Party, a moderate Tamil group” in item 10 is a noticeable error. It needs rebuttal. In reality, this fringe group functioned as a para-military arm of Chandrika Kumaratunga’s army.

****

A typo error in the first sentence of Item 1, needs correction.

The age of Corporal Rana was 26, and NOT 2. The error is regretted.