Captain Pandithar and a Collection of 1985 Editorials in International Newspapers

by Sachi Sri Kantha, September 29, 2025

Prelude

Proper chronological dating of events is important to history. When did the so-called Sri Lankan civil war start? Majority of journalists (indigenous and international varieties) historians, politicians as well as those dimwit Wikipedia entry twisters opt for July 1983 as the starting point of Eelam War I. I will choose January 9, 1985 for one important reason. It is this.

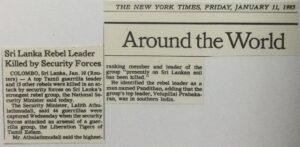

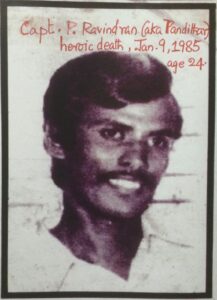

LTTE’s then leader of Jaffna region, Capt. Pandithar (aka, P. Ravindran), aged 24, was killed in Jan 9th, 1985, in an encounter with the Sri Lankan army at Achuvely, Jaffna. He was then, the nominal No. 2 of LTTE. A brief Reuters report that appeared in The New York Times (Jan 11, 1985) at the ‘Around the World’ news snippets had recorded this.

Please check the original, scanned nearby, and note that this was State security minister Lalith Athulathmudali version of the encounter.

Its caption was ‘Sri Lanka rebel leader killed by Security Forces’. To quote, “A top Tamil guerrilla leader and 13 other rebels were killed in an attack by security forces on Sri Lanka’s strongest rebel group, the National Security Minister said today. The Security Minister, Lalith Atthulathmudali, said 44 guerrillas were captured Wednesday when the security forces attacked an arsenal of a guerrilla group, the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam.

Mr Athulathmudali said the highest ranking member and leader of the group ‘presently on Sri Lankan soil has been killed.’ He identified the rebel leader as a man named Pandithan, adding that the group’s top leader, Velupillai Prabakaran, was in southern India.”

More details about the Jan 9, 1985 confrontation between the Sri Lankan army and the LTTE fighters, as well as the LTTE version of Capt Pandithar’s heroic death are available in Viduthalai Puligal (April 1985, p. 12). It was captioned ‘Heroic death of a Liberation Tiger’. An English translation follows:

“One of the leading figures of Tigers, Capt P. Ravindran (aka Pandithar) attained heroic death in a recent confrontation between the guerrilla team of Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam and Sinhalese military. This happened on January 9th at Achuveli village in Jaffna district.

Capt Pandithar aka P. Ravindran

Suddenly a large number of Sinhalese military folks surounded our guerrilla base at Achuveli. Following this, a big confrontation occurred between our liberation fighters and the military. This lasted for a long duration. Until the end, Capt Ravindran fought and lost his life for the conviction he had on liberation. In addition to Capt Ravindran, four other young Tigers also attained heroic deaths. Other fighters were able to escape from the scene of confrontation.

Capt Ravindran was a Central Committee member of Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam. In addition, he was in charge of finances and armory sections. He was a native of Kamparmalai, adjacent to Valvettiturai. He was 24. He joined the Tigers movement in 1977 and worked prominently. Duty, hard work and belief in the ideals were his forte. Due to this, he came to be respected by fellow peers. As such, he became the ‘right hand’ of the LTTE’s leader V. Prabhakaran. In addition to undertaking the responsibilities of the movement, he also participated and contributed to the guerrilla warfare used by the movement. For this heroic soul who set the path for Eelam liberation, we Liberation Tigers offers the heroic salute.

As per the Achuvely confrontation, Sinhalese government had spread fake propaganda: that the military quarters of Tiger movement had been destroyed, that Tigers had been completely eliminated were samples of such spread. There is hardly any truth on such fake propaganda. This we assert. There are quite many big and small military bases for Tigers in Tamil Eelam.

One small military base in Achuvely was the one which suffered from such a confrontation. Unexpectedly, our 15 guerrilla warriors assembled in that base had to tackle over 500 military guys of other side with heavy weapons. In this confrontation, 10 Tiger guerrilla warriors fought valiantly, and left the scene of conflict unhurt. This has to be noted as a positive record in battle field. Following this, military guys arrested 50 innocent youths from Achuvely, tagged them as ‘terrorists’ and self-congratulated themselves with laurels, for false propaganda purposes. Days are not too long for us to teach a lesson to the Sinhalese government for their attempt to destroy the independence struggle of Tamils.”

One could infer that LTTE learned a vital lesson in its loss of Capt Pandithar. This was about plugging intelligence leaks from the community. That’s why, Prabhakaran and his advisors established a strong intelligence gathering network, to protect the Tamil homeland, much to the discomfort of paid Tamil snoops and human rights barkers.

There are also quite a few other reasons, for setting Jan 9, 1985 as the origin of Eelam war I. One of which is the international perception, as described in the collection of editorials in international newspapers of 1985, which I reproduce below. For example, please check the editorial caption for The Tines (London), dated Aug 26, 1985.

For record, I provide 11 such editorials in my collection first, and offer my commentary on these at the end.

☆Lanka’s communal clashes. Arab News (Jeddah), Apr 27, 1985

☆Ending discord in Sri Lanka. Christian Science Monitor, Apr 30, 1985

☆Lanka: Time running out. Arab News (Jeddah), May 18, 1985

☆Conciliation in Colombo. The Times (London), May 25, 1985

☆Tamil Fears The Times (London), May 29, 1985

☆Sri Lanka’s fearful symmetry. New York Times, May 29, 1985

☆Intimidating the Tamils. Observer (London), June 2, 1985

☆Rajiv’s stakes in Lanka. Arab News (Jeddah), June 20, 1985

☆Closer to Civil War. The Times (London), Aug 26, 1985

☆No ceasefire this. Times of India, Oct 7, 1985

☆Resuming Talks. Times of India, Dec 4, 1985.

Lanka’s communal clashes.

[Arab News (Jeddah), Apr 27, 1985]

The chasm of blood and tears that separates the illusion of the idyllic isle of smiles which the Sri Lankan tourist brochures still try to project and the ugly and bitter realities in the island state seems to be widening day by day. First it was a fight between a minority within the Tamil minority fighting for a separate state and a government trying to contain the forces of disintegration. The ethnic riots in July 1983 changed the whole scene which since then has been marked by deep distrust and mutual suspicion and occasional clashes between the majority Sinhalese and minority Tamils with the government sometimes giving the impression that its priorities were determined by the Sinhalese, rather than nationalist considerations. With the clashes between Muslims and Tamils, Sri Lanka now seems to be going through something approaching a civil war on two fronts – one between a majority and minority and the other between two minority groups.

According to the latest reports, the Muslim-Tamil clashes have claimed about 55 lives in the past two weeks. This is only part of the story. Some 1,500 homes and shops have either been burned or damaged and 35,000 people have fled their homes to carry the tales of their woes and seeds of hatred to hitherto unaffected areas. Home Minister Bill Devanayagam suspects the sinister hand of a foreign power behind the clashes between Muslims who constitute seven percent of the population and Tamils whose strength is more than twice that of Muslims.

Devanayagam may have his own reasons to suspect that Sri Lanka may be offering itself too tempting an attraction for those who are out to destabilize governments and social structures. Others claim they have more valid reasons in seeing the origin of the clashes in the internal compulsions of political life in the island state. According to this theory, the clashes are the handiwork of those who are either seeking some diversionary tactics or want to dissipate the energies of Tamil separatists by forcing them to fight on two fronts. This will also serve the purpose of painting the Tamils in the blackest of colors. If this is what the Tamils can do to another minority living in their midst, the argument goes, you can very well imagine how they would behave when the real power passes into their hands.

Now there may be an element of truth in all these theories. Only and impartial inquiry can bring the true facts to light. This is what the Sri Lankan Muslims and Sri Lanka’s friends abroad expect of the government. Quixotic tilting at the windmills will not do.

****

Ending discord in Sri Lanka.

[Christian Science Monitor, Apr 30, 1985]

Even as an unacceptable level of violence continues in Sri Lanka, evidence emerges of diplomatic stirrings between that nation and India. It is to be hoped that those stirrings lead to a working relationship between two wary neighbors. Such a step is prerequisite to restoring peace to a now badly divided Sri Lanka.

Early this year India’s new prime minister and Sri Lanka’s minister of security discussed the Sri Lankan problem; later a top Indian official went to Sri Lanka to continue the discussions. In addition, India appears to be monitoring more closely the comings and goings of militant Tamils between southern India and Sri Lanka. Sri Lanka’s Sinhalese majority insists, and India denies, that the militant Tamil rebels gain much of their training and support from the large Tamil community in nearby southern India.

The current violence has its roots in centuries of division between Sri Lanka’s majority Sinhalese and minority Tamils. Each side is deeply suspicious and fearful of the other. Differences of religion exacerbate the division. A growing minority of Tamils eschews political settlement in favor of force of arms; moderate Tamils, who seek more power by peaceful means, are paid little attention.

For two years conflict has waged openly: Militant Tamils attack government military forces; an undisciplined Army dominated by Sinhalese attacks Tamils. Both sides believe time is on their side. Tamils think the government will eventually tire and give in to militant demands for partition. Sinhalese feel that if the government continues to bear down hard on the militants, Tamil moderates eventually will strongly oppose their violence-prone brethren.

It is more probable that time is on neither side, that only stalemate would lie ahead of continued violence. When both sides realize this, and there is no evidence that either now does, they will have taken an important step toward solving the problem.

Other elements will also be necessary. One is for the majority Sinhalese government to be willing to share some of its power over Tamil-occupied northern and eastern territories with the Tamils themselves. The government, and the Sinhalese community at large, are now deeply divided over this issue. Moves by Sri Lankan President Jayewardene toward modest devolution of power have been sharply rebuffed by conservative Sinhalese.

For its part India should make it clear to the Tamils that it will not step in and promote a settlement with the Sri Lanka government. As the largest and most powerful nation on the Indian subcontinent, India has a protective view of its role toward neighboring nations, including Sri Lanka. In 1971 India moved into rebellion-torn Bangladesh and restored order. Militant Tamils may feel that if the strife in Sri Lanka worsens seriously, India will send its forces into Sri Lanka to restore order on terms more favourable to the Tamils. It is up to India to show such restraint toward these Tamils that they will realize such a step is unlikely, and that they will be more willing to move toward accommodation.

When all the factors come together, the stage will be set for a political accommodation between the Sinhalese and Tamils that will restore peace to Sri Lanka. The United States government supports a political settlement, and it has been quietly urging that India take a constructive role in helping to bring it about.

****

Lanka: Time running out.

Arab News (Jeddah), May 18, 1985

It is difficult to know whether Sri Lanka is heading toward the precipice or had already gone over. The country appears to be tearing itself apart n an orgy of intercommunal violence. No one is spared. Even the Muslim community has been dragged into the conflict. And while Sri Lanka burns, its government stands by, powerless, seemingly incapable of preventing this attempt at national suicide.

In the past three days, some 220 people have been murdered. One hundred and forty five were Sinhalese gunned down in cold blood on Tuesday in the city of Anuradhapura by fanatical Tamil terrorists. The place was sprayed with machine-gun fire. They killed everyone and anyone in sight.

On Wednesday the reprisals started. A ferry carrying 60 Tamils from an island off the north coast was attacked by two boats and some 50 were killed. Reports that it was a naval group on the rampage who were responsible do not sound particularly far-fetched. In the past two years there have been a number of cases where soldiers have gone amok, slaughtering any Tamil they could find.

The attack on Anuradhapura was a deliberate act of provocation on the part of the Tamil terrorists. The city is sacred to the Buddhists. Most Sinhalese are Buddhists. The Tamils are Hindus. Such is Sinhalese outrage that there is every possibility of another convulsion like the one in 1983 when hundreds of Tamils were killed and thousands rendered homeless in riots following the death of 13 soldiers in an ambush in Jaffna.

It is easy to blame the terrorists for the island’s troubles. They are evil men who care nothing for the misery they cause to Sinhalese as well as to their own fellow Tamils who invariably end up suffering the consequences of the terrorist activities.

But Sri Lanka’s problem is a political, not a military one. Defeating the terrorists is only a small part of what needs to be done. The Tamils are increasingly alienated. President Jayewardene needs to come up with a political response. This he has failed to do.

He has also failed to do anything about the question of discipline in the Sri Lankan armed forces. Discipline in the army seems to be fast disappearing. An army without discipline, that goes on the rampage, is worse than useless; it is positively dangerous. It attacks on innocent Tamils serve only to convince the Tamils that there is no place for them in Sri Lanka.

If President Jayewardene wants to maintain Sri Lankan unity, the first thing he must do is to prove to the Tamils that they can have confidence in the security forces. Military discipline must be restored. A few well-publicized court-martial could work wonders.

Unless he acts decisively and quickly, the Tamils will be pushed into the arms of the terrorists.

The ball is in his court. Urgent action is required.

****

Conciliation in Colombo.

The Times (London), May 25, 1985

The Sri Lankan Parliament has ended the week in emergency session to debate the country’s rising toll of inter-communal massacres.

In May alone so far, according to some accounts, more than 300 Tamils and Sinhalese have been killed. Another 100,000 Tamils are refugees in India while more than 2,000 are now seeking shelter in Britain. Despite almost two years of a continuous state of emergency the rift between the two main communities is greater than ever before. Yesterday it became clear that President Jayewardene is under pressure to seek a political solution, he has responded instead by threatening martial law.

If the Jayewardene Government is to escape further blame for its handling of the problem it will have to turn with the tide, against a military solution. The President already has a lot to answer for. Although the origins of this crisis hark back to the traditional ethnic and cultural rivalries between the Aryan Sinhalese and Dravidian Tamils, exacerbated by a deliberate policy of British preference for the Tamils whilst Ceylon was a Crown Colony and a crude reverse Sinhala-first redressal after independence, a large share of the blame for the present near hopeless state of communal relations must lie with the Jayewardene Government.

During the period of formal negotiations with the Tamils, the President failed to rise above politics and his ruling United National Party’s own concern to make a serious offer which moderate Tamils, and in particular the Tamil United Liberation Front, could reach out and grasp. Instead, by clinging rigidly to the narrow position of the Buddhist Sinhalese clergy and his party’s hardliners, he ended up discrediting the TULF in the eyes of its own Tamil supporters and forcing the Tamil middle ground into the clutches of the extremists and their terrorist tactics.

More importantly, however, since the predictable collapse of the all-party conference at the end of last year, the policy Mr Jayewardene pursued exposed his lack of a truly sensitive national vision. Instead of intensifying his attempts at trying to find a negotiated solution, his government opted for what amounts to a military settlement, relying on it indisciplined forces to tackle the terrorists without any corresponding political initiative to win back majority Tamil sentiment. Indeed, to add insult, it also repeatedly committed itself to settling Sinhalese on Tamil land, a policy that could not have been more deliberately designed to offend.

It is against this bleak background that this month’s massacres have occurred. They are a measure of the despair and desperation which is now widely spread through both Sri Lankan communities.

It is therefore imperative that the Government pay heed to the calls to seek a political solution by means of fresh negotiations which have this week been made in Colombo. Even leading members of the Buddist clergy, numbed by the brutality of the wanton murders, seem to have come out in favour of another conciliatory conference with the Tamils. In fact, this time round President Jayewardene is being urged to sit down with both the terrorists and the Indian Government (which he believes supports the former) to find a solution. It is an opportunity he should not miss.

For, paradoxically, the May murders may have pushed Sri Lanka’s crisis to its nadir but have also created for President Jayewardene, were he willing to take it, the best opportunity yet to press for political concessions to the Tamils. As the military approach has so visibly failed, the majority Sinhalese are for the moment prepared to try negotiations once again. In their present mood, the President might just get them to accept a solution they would earlier have rejected. At the same time, with the terrorists internationally discredited for their part in the Anuradhapura killing, the President may also find the TULF suddenly more willing to respond to his overtures. While the terrorists are temporarily laid low the moderates could steal back into the limelight. It all depends on the President’s handling.

****

Tamil Fears

The Times (London), May 29, 1985

For a year until last week Sri Lanka Tamils arriving in Britain and seeking entry out of fear for their safety in their own country were provisionally regarded as deserving temporary refuge. They were refused leave to enter but the refusal was not acted upon. They could remain, though they might at any time be sent away. None has yet been sent back.

By the beginning of last week, some 900 Sri Lankan Tamils were here under those precarious terms. (There are now 1,400 or 1,500, the pace of arrival having accelerated markedly.) At that point the Home Secretary announced a change of treatment. In future any Sri Lankan Tamil who does not qualify for entry under the immigration rules yet fears for his safety if returned will have his case examined on its merits. He will be allowed to stay for twelve months in the first instance provided he can show there is reason to believe that he would suffer ‘severe hardship’ if he returned to Sri Lanka. If he cannot show reason he must go back. The criterion is less onerous than the standard criterion for asylum, which is ‘well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular group, or political opinion.’

It is a paradox that, whereas in April 1984 the expression of fear was accepted as a reason not to be sent back immediately to Sri Lanka, in May 1985, when the dangers in that country are appreciably greater, demonstration of the grounds of fear is additionally required. In spite of that paradox the Home Secretary is justified in making the change.

At this end the apparatus of immigration control is feeling the strain of the quickened pace of arrivals and the accumulation of entrants for whom rejection has been temporarily suspended. A signal to the Tamils in Sri Lanka that applications will be searchingly sifted from now on may ease the strain. Even more to the point is the possibility of the disturbances in Sri Lanka being used as a pretext for evasion of the strictness with which our immigration controls are habitually enforced, a strictness that is one of the props of reasonably good race relations within Britain. It is not that the fears of the Tamils who come were in the posture of fugitives are necessarily pretended, but that the fears, even when genuine, may lack substantial cause.

At the Sri Lankan end the condition of the country is not such that flight is a compelling course for the Tamil minority in general. Communal massacre of the kind that erupted briefly in 1983 has not returned. The security measures executed on behalf of the Sri Lankan government, though sometimes hideously ill-disciplined and tragically misdirected, are aimed at Tamil terrorists and their organizations. Most of the country is tranquil. The elements of democracy and the rule of law remain though battered a bit. Conditions for the Tamils are worst in the north of the island, where ethnic and personal links make Tamil Nadu in south India the natural refuge.

This is not to say that Britain should turn its back on the plight on Tamil refugees, or that none of those who come here purporting to be of that description has a true claim. It is to say, with the Home Secretary, that it is right to insist that cases are individually made out. But if that requirement is imposed, the opportunity to make out a case must be properly provided.

Time and access to advice must be afforded; and if someone is fleeing for his safety it is little consolation to be told that he has a right of appeal after he has been returned to the place of supposed danger. It is in these respects that the procedures now adopted leave room for doubt as to their humanity and fairness.

****

Sri Lanka’s fearful symmetry.

New York Times, May 29, 1985

Solomon Bandaranaike is half-remembered as a lively, leftist Prime Minister of Ceylon, the tear-shaped island nation now called Sri Lanka. His story is worth retelling, for it helps in understanding why Sri Lanka is squandering its prosperity in a bitter civil war; between the Sinhalese majority and the Tamil minority.

Mr Bandaranaike belonged to a prominent Sinhalese Christian family with close ties to the British. His father helped found the Colombo Turf Club. But when the son returned from Oxford in the 1930’s, he converted to Buddhism, adopted national dress and espoused leftist and nationalist causes. His party came to power in 1956, just as Ceylon was celebrating 2,500th anniversary of Buddha’s attainment of Nirvana. Riding with this fervor, he endorsed promoting Buddhism and making Sinhalese the official language of the new nation.

Language became the explosive question. The Sinhalese, comprising three-fourths of the population, felt cheated of their share of good jobs and pay. They blamed the British for favoring the Tamils, a Hindu people with their own language. So the new Prime Minister approved a ‘Sinhala Only’ policy to handicap the more prosperous minority.

But he also proposed allowing ‘reasonable use’ of Tamil, for which he was instantly condemned by Sinhalese radicals. Communal riots cost hundreds of lives. In the Tamil north, the Sinhalese script was defaced, and in the Buddhist south, monks organized angry sit-ins. The Prime Minister retreated, but not fast enough. On Sept 25, 1959, he was murdered by a Buddhist priest.

The wheel has turned, but nothing has happened to end the estrangement between two peoples who have shared the island for centuries. Junius Jayewardene, Sri Lanka’s President today is a conservative whose free-market policies have doubled per capita income for 16 million Sri Lankans. But it is prosperity without peace. Some Tamils have resorted to insurgency and agitate for independence. The defense budget has welled tenfold in five years, and 600 people have been killed in six months.

The Government has turned to Israel for military advisers. Tamils have turned to India, where 50 million Tamils dominate a nearby state. Mr Jayewardene warns he may impose martial law and rejects negotiations with Tamils who even hint at separatism. Waylaid is the President’s cautious offer of greater autonomy. Faced with a backlash from Sinhalese extremists, Mr Jayewardene had to retreat. Nothing better can be expected from the opposition party, led, as it happens, by Prime Minister Bandaranaike’s widow, Sirimavo.

Bigotry in Sri Lanka has defeated left and right. It is a fearful symmetry that beggars optimism.

****

Note by Sachi: A Factual error needs correction. Solomon Bandaranaike returned to Ceylon in 1925, and not in 1930s.

Intimidating the Tamils.

Observer (London), June 2, 1985

The Government has been panicked into illiberal and probably unnecessary steps in its attempts to discourage Tamil refugees arriving in Britain. This so-called ‘flood’ of refugees amounts to some 1,500 people, fewer than have gone to either West Germany or Switzerland – neither of them countries with any traditional links with Sri Lanka. The great majority would have returned home after their six or 12 month stay in Britain ran out. But in matters like these, the Home Office is easily panicked.

The Tamils in Sri Lanka face a desperately difficult situation, It is small consolation for them to be told that it was the acts of their own extremists, the Tamil Tigers, which provided a pretext for the repression of their whole community. There is ample evidence that the Sri Lankan security forces, while unable to take any effective action against the terrorists, have been involved in many acts of indiscriminate violence against innocent Tamils. Young men are particularly at risk of arbitrary arrest and detention, or worse. Many have been torn from their homes, or off buses, doused with petrol and burned. Small wonder that some have tried to escape.

The answer, of course, does not lie in large-scale emigration of Tamils from Sri Lanka, as the Tamil organizations there are the first to insist. But was that ever a serious prospect? Under the old rules, Tamils coming into Britain had to possess a return ticket and sufficient money to support themselves, a financial barrier substantial enough to exclude all but a small minority. Now they will have to queue up at the High Commission in Colombo to seek a visa, exposing themselves to observation by the security forces. In theory, the procedure is designed to sort out ‘genuine’ refugees from the rest; in practice, it is hard to escape the conviction that it is simply designed to frighten Tamils off.

The introduction of visas would be more defensible if the Government had made a greater effort to improve the situation inside Sri Lanka, one of Britain’s largest aid recipients. Britain should say clearly to the Government of Mr Jayewardene that it expects dramatic improvements, soon, in the behavior of his army and police. Without such changes, the situation in Sri Lanka will collapse into chaos and bloodshed on an unprecedented scale, with an exodus of refugees which will make the present ‘flood’ look like a light spring shower.

****

Rajiv’s stakes in Lanka.

Arab News (Jeddah), June 20, 1985

Rajiv Gandhi’s popularity at home has reached a new high. He has just returned from a highly successful five nation tour which he handled with consummate skill. He drew praise in Washington, Paris, Algiers, Cairo and Geneva. Back home in Delhi there is satisfaction that the man who was once described as inexperienced and untried has proved himself to be a statesman.

But affairs much closer at hand (one might say in India’s backyard) could destroy Gandhi’s political reputation. Sri Lanka poses as much a crisis to the Indian government as it is to that of President Junius Jayewardene.

The latest development in the island’s anarchic civil war is a ceasefire pending talks. Five Tamil separatist groups, including the notorious Tigers have agreed to join in.

This is the first good news to have come out of Sri Lanka for some time. It has been clear for a long time that a political settlement is the only possible solution to island’s communal conflict. Even the head of Sri Lankan Army acknowledges this. ‘We can never win’, he declared candidly earlier this year.

But substantial concessions involving a radical restructuring of the island’s institutions will have to be made by the government if the Tamils are to give up their demand for an independent state. But will the Sinhalese majority, who account for 72 percent of the total population let Jayewardene to do that?

The government is in an almost impossible situation – so much so that it is terrified of telling the people what is going on. Nor is it helped by the personal animosity between Jayewardene and Mrs Bandaranaike who, though debarred from politics, remains the guiding force behind the other main Sinhalese party. Without her support there is no possibility of a settlement.

But why, you may wonder does all this concern Rajiv Gandhi?

The reason is that he is one of the leading lights behind the ceasefire. Following talks with Jayewardene in New Delhi earlier this month, he put pressure on the Tamil rebels, who are based in the south Indian state of Tamil Nadu.

The danger is that taking such an active role in the Sri Lankan conflict could easily backfire.

The five Tamil guerrilla groups have put conditions on their joining in the truce. They will not attack but they will defend their communities if they are attacked. The trouble is that there are a few small hard-line Tamil guerrilla groups which are not joining in the ceasefire. They are implacably opposed to it. There is every possibility that they will attack the army so as to provoke retaliation against Tamil villages and thereby bring the whole ceasefire crashing down.

This would affect Rajiv directly. He has already been under strong pressure from Tamil Nadu and elsewhere in India to support the Tamils. The failure of the ceasefire or the planned talks would force him to do just that. India would be drawn inextricably into the Sri Lankan conflict.

Memories of the 1971 war with Pakistan and the creation of Bangladesh should deter Rajiv from going any further. But it may already be too late to extricate himself from this mess.

****

Closer to Civil War.

The Times (London), Aug 26, 1985

The second round of peace talks to settle the deeply entrenched communal rift in Sri Lanka collapsed in discord last week. It had been expected that they would provide the framework for a resolution of the Sinhalese-Tamil conflict. Instead they became lost in the cavernous divide that separates the two sides.

Worse still, with the entailed embarrassment of the Indian government, which had sponsored the talks, the best remaining hope of resolution has faded. Now Sri Lanka is not just back to square one but very possibly on the brink of civil war.

The primary responsibility for this outcome rests with the authorities in Colombo. At the June summit between Sri Lanka’s President Jayewardene and Mr Rajiv Gandhi, the Indian Prime Minister, which laid the foundations for the three months ceasefire and the Bhutan negotiations, the Sri Lankans appeared to be willing to accept reality and make meaningful concessions to the Tamils. It was understood that these would include a substantial devolution of power. In turn the Indians cajoled the Tamil guerrillas, based in South India, into forsaking their demand for an independent Eelam.

Yet when the two sides met in Thimpu for their first set of talks the Sri Lankan team failed to match that expectation. The peace process was saved by an adjournment and by the time the second round began earlier this month, the Indians had secured reconfirmation from President Jayawardene of his willingness to compromise. Indeed on this occasion the president even went on record claiming that he was confident of ‘good results’. But, back at the negotiation table, his delegation once again had little to offer, and as tensions on the island flared up with the massacre at Vavuniya, the Tamil delegates walked out of the talks.

The Tamils, it is believed, would have settled for control of finance, education and law and order. Certainly Mr Rajiv Gandhi had repeatedly and publicly committed himself to supporting no more than the sort of devolution given to the States in India, which he explained, was ‘considerably less than the American federal system’. If, President Jayawardene had offered as much Mr Gandhi could have seen to its acceptance. But the Sri Lankan President was unable to defy his own right wing and the Buddhist clergy, both of whom have refused to countenance any real devolution of power. Consequently, all that was offered was a repackaged version of the district council scheme already rejected by the Tamils in 1984. In the circumstances it was bound to be unacceptable.

For their part the Tamil guerrillas did not assist a solution by formally tabling what they called a ‘liberation charter’. In it they demanded from President Jayawardene recognition of a distinct Tamil nationality, of a Tamil homeland and of their right in self-determination. On the face of it, these claims contradicted any willingness to compromise.

Yet while the peace process was on the Indian government could have reined in Tamil demands. With its collapse India’s capacity and perhaps its willingness to do so could now be in doubt. With a fifty million strong Tamil population of his own to consider, at best wary of Mr Gandhi’s pressure tactics, he cannot easily repeat his strategy even if Colombo has a sincere and convincing change of heart. Perhaps this is why he has chosen instead to expel some of the more belligerent guerrilla leaders. It may be a way of putting fresh pressure on the Tamils to make there own concessions, but that is unlikely. Instead, it would suggest that Mr Gandhi is washing his hands of the problem.

This leaves the Sri Lankan government to face the Tamil, guerrillas on its own. Already the island is effectively split between an embittered Tamil north and east and an unrelenting Sinhalese south and centre. The present flood of refugees towards the areas where their respective communities dominate will further exacerbate this divide. And with the guerrillas having called off the ceasefire, the possibility advances of protracted and bloody civil war.

****

No ceasefire this.

Times of India, Oct 7, 1985

It is evident that Sri Lanka’s armed forces have stepped up their attack on Tamil civilians as well as Eelam guerrillas. During the past week they have raided three guerrilla ‘bases’ in the northern and north-central provinces, killing at least 32 militants; and in the east, a massive military operation has been launched against civilians in which nearly 400 ‘suspects’ have been arrested, a leader of the Eelam revolutionary organization of students killed, and thousands of Tamils driven out of their homes. This is not the first occasion on which the Sri Lanka armed forces have violated the ceasefire arrangements agreed upon at the second round of talks on the Tamil issue at Thimpu and reiterated subsequently in New Delhi. The violations of the ‘second ceasefire’ extended beyond the original three-month period ended on September 18 have been both numerous and widespread. For instance, no fewer than 52 villages in Trincomalee were destroyed by Sri Lankan forces within the first week of the ‘second ceasefire’ and 15 Tamils were shot dead in cold blood at Kalvettu in the eastern Amparai district. This is of course in line with what the Sri Lanka soldiery did during the first ceasefire in which, the Tamil militants claim, more attacks were made on the ethnic minority than in the preceding quarter.

What makes the current anti-Tamil military operations singular in importance is not so much their scale which is considerably higher than before. It is the fact that they are taking place amidst reports that the Sri Lanka government has suspended, at least temporarily, the appointment of a local panel of observers to monitor the ceasefire. The French news agency, AFP, has now quoted a member of the panel as saying that he has been informed that the entire proposal is being ‘shelved’. All this and the continuing butchery of Tamils clearly calls for a thorough reappraisal of the situation in Sri Lanka. It is apparent that there has been a considerable hardening of the Sri Lankan stand towards the Tamils and that Colombo has used the opportunity provided by the ceasefire, the Thimpu talks and the weakened position of the guerrillas to evacuate Tamils from a large zone stretching from Mullaitivu to Trincomalee in the east and to launch ferocious attacks upon them in the north. Meanwhile, Sri Lanka’s national security minister, Mr Lalith Athulathmudali has announced plans to build a 100,000-strong military and paramilitary force to tackle the ‘terrorists’. It is impossible to see any of this as a response provoked by the recent attack by some Tamil militants on a police station. The conclusion is inescapable that Colombo is less than serious about reining in its security forces. It is time New Delhi reviewed the options open to it in providing its good offices and considered seriously the Tamil militants’ proposal for an independent international body to monitor the ceasefire agreement.

****

Resuming Talks.

Times of India, Dec 4, 1985

No sooner had the Indian high commissioner in Sri Lanka, Mr. J.N. Dixit, announced in Colombo, after a meeting with the Sri Lanka national security minister, Mr Lalith Athlathmudali, that the Eelam National Liberation Front (ENLF), comprising of four guerrilla groups, as well as a fifth, the People’s Liberation Organisation of Tamil Eelam (PLOTE), were ready to resume negotiations with Colombo through the TULF than an ENLF spokesman denied any such willingness on its part. At the same time, he added that ‘the TULF or any other group can participate in the peace processes on their own, if they want to’, although it could not speak for the ENLF. PLOTE has taken the same stand as the ENLF. While the TULF, which represents moderate Tamil opinion, is preparing to renew the talks, these parleys would necessarily be limited without the participation of the guerrillas. That, however, is no reason for not trying to break the current stalemate. Since, according to the independent Colombo newspaper, ‘Weekend’, the Sri Lanka side will be led by Mr Athulathmudali, Colombo is giving the resumption of the talks high priority. On the agenda will apparently be the working paper on devolution and other proposals drawn up earlier by Mr. Hector Jayewardene as well as TULF counter-proposals.

The conflict between the Sri Lanka government and the Tamil guerrillas shows every sign of intensifying. With the ceasefire having collapsed and the committee set up to monitor it rendered ineffective, it is as good as back to square one on the island. Only a few days ago, no less than 45 Tamils were killed in two separate incidents in the Batticaloa and Trincomalee districts of the eastern province. While official statements said all the victims were militants, other reports indicate that they included a number of civilians. The eastern province is now a particularly fierce arena of bloody conflict. What is especially disquieting is that both sides appear to be digging into hardline positions. Colombo is spending a great deal of money on beefing up its security forces, while for their part, the guerrillas remain convinced, as Mr. S.C Chandrahasan, the co-ordinator for India of PROTEG (the body for protecting Tamils of Eelam from genocide), has said, that Colombo is engaged in the systematic annihilation of the Tamil minority. The Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam chief, Mr V Prabhakaran, has spoken of the futility of talks and of how the ‘establishment of an independent sovereign state will be the only solution’. Given these uncompromising attitudes, it becomes all the more urgent to crank the stalled peace process into motion again.

****

Commentary

Why I present this collection of editorials, after 40 years, for digital preservation? This is an earliest draft of Tamil history in Sri Lanka during our life time by non-Sri Lankan scribes, albeit with errors in interpretation and filled with bias. On one particular issue, the non- Sri Lankan editorialists were unanimous. This is about the non-professional conduct of the Sri Lankan army aka Sinhalese army in the 1980s. Not only Colombo-based journalists, but even academics were too scared and ashamed to openly express this vital fact. I won’t be wrong, if I impress the point that it was this unruly behavior of the Sinhalese army in the Northern province, between 1977 and 1983, that caused the origin of Eelam Tamil militants.

What I wish to stress is that the editorialists of the above sources were NOT oracles. They have their knowledge deficits on Sri Lankan history, culture and languages, as well as potent biases originating from their land. For example, New York Times and Christian Science Monitor do carry ‘Yankee truth’ bias. The Times (London) and The Observer (London) are enriched with colonial ruler bias. Arab News (Jeddah) has an Islamic bias. Times of India has ‘Big brother’ bias. Nevertheless, these biases are a degree lower than the ‘Mahavamsa mind set’ bias prevalent among Colombo-based scribes.

40 years ago when these editorials were prepared, we lived in simpler analog times. Personal computer was in its early models. Correspondence by air mail post was the routine of the day. No internet, no email and no digital based news-platforms. In 1985, I was in my final year of the PhD program at the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign. To gather news from Sri Lanka, once or twice a week, I visited the Newspaper library at the campus, and copied any pertinent items about Sri Lanka that appeared in newspapers, at the library’s photocopier. The charge was a nickel (5 cents) per page.

I provide other reasons for setting the beginning of Sri Lankan civil war (between the Government of Sri Lanka and LTTE) to Jan 9, 1985.

First, the Ministry of National Security was established on March 24, 1984, and the appointed top dog was Mr. Lalith Athulathmudali (1936-1993).

Secondly, Sri Lanka’s annual defence budget showed a 3.47 fold increase from 48.48 million US dollars in 1984 to 168.39 million US dollars in 1985. At that time, the currency exchange rate for 1 US$ was equivalent to only 26 or 27 SL rupees! In May 2009, when LTTE was defeated by Sri Lankan army, the 1 US$ was equivalent to ~114 SL rupees. Now (Sept.28, 2025), the 1 US$ equals 301 SL rupees.

Thirdly, until 1984, all the Tamil militant groups (TELO, LTTE, PLOTE, EROS, EPRLF and other ephemeral groups) were jointly identified as ‘Tigers’ or ‘Boys’. Only in 1985, LTTE gained prominence due to their devotion to the Eelam cause and captured the ‘Tiger’ moniker permanently.

Fourthly, following Indira Gandhi’s assassination on Oct 31, 1984, Rajiv Gandhi became Indira’s successor by popular verdict only after Dec 28, 1984 Lok Sabha general election. More than Indira Gandhi’s strategy, it was the naivete and inexperience of Rajiv Gandhi in tackling the LTTE as well as J.R. Jayewardene that caused the origin of Sri Lankan civil war. The son proved to be an empty shell of mother’s tactical guile in dealing with Jayewardene.

Fifthly, Time magazine (International edition) published a cover story on Sri Lankan conflict on June 9, 1986. Writing about the origin of LTTE, Marguerite Johnson had recorded “…for years the Tamil rebellion consisted of much talk, with only an occasional bombing or killing. By mid-1983, Prabhakaran’s Tigers had only 30 full time members, with far less than one gun apiece.” What does this mean? Prabhakaran was NOT a fool, to begin the Eelam war with only 30 full time members and lesser number of guns. From July 1983, for the next 18 months, LTTE did increase its cadre strength to a reasonable quantity as well as armory to sustain a war, until January 1985.

Despite all the adverse environment, and adverse propaganda at the local, regional and global level, Prabhakaran and his devoted followers did sustain the civil war for 24 years. This he couldn’t have achieved with a conscripted army of teenagers, as his adversaries had claimed.

****