by Sachi Sri Kantha, December 2, 2013

I provide below an autobiographical document, which I solicited eleven years ago. The author of this document is my father, who died in October 20, 2003 after reaching 80 years. When he wrote this, he was ailing from bladder cancer. Somehow, he persevered to complete this assignment, for the benefit of his grandchildren. I regret that I should have made my request ahead of time, when his childhood memories were fresh and he was in good health.

Why I provide this material now, is to suggest that elders living in diaspora should record their childhood memories in Tamil Eelam, while in good health, for the benefit of their descendants who may not have opportunity to live there. Such ethnological vignettes can only be produced by Tamils. This becomes vital, when mass scale debunking of Tamil heritage and history is being perpetrated by the anti-Tamil forces (some of whom were born Tamils!).

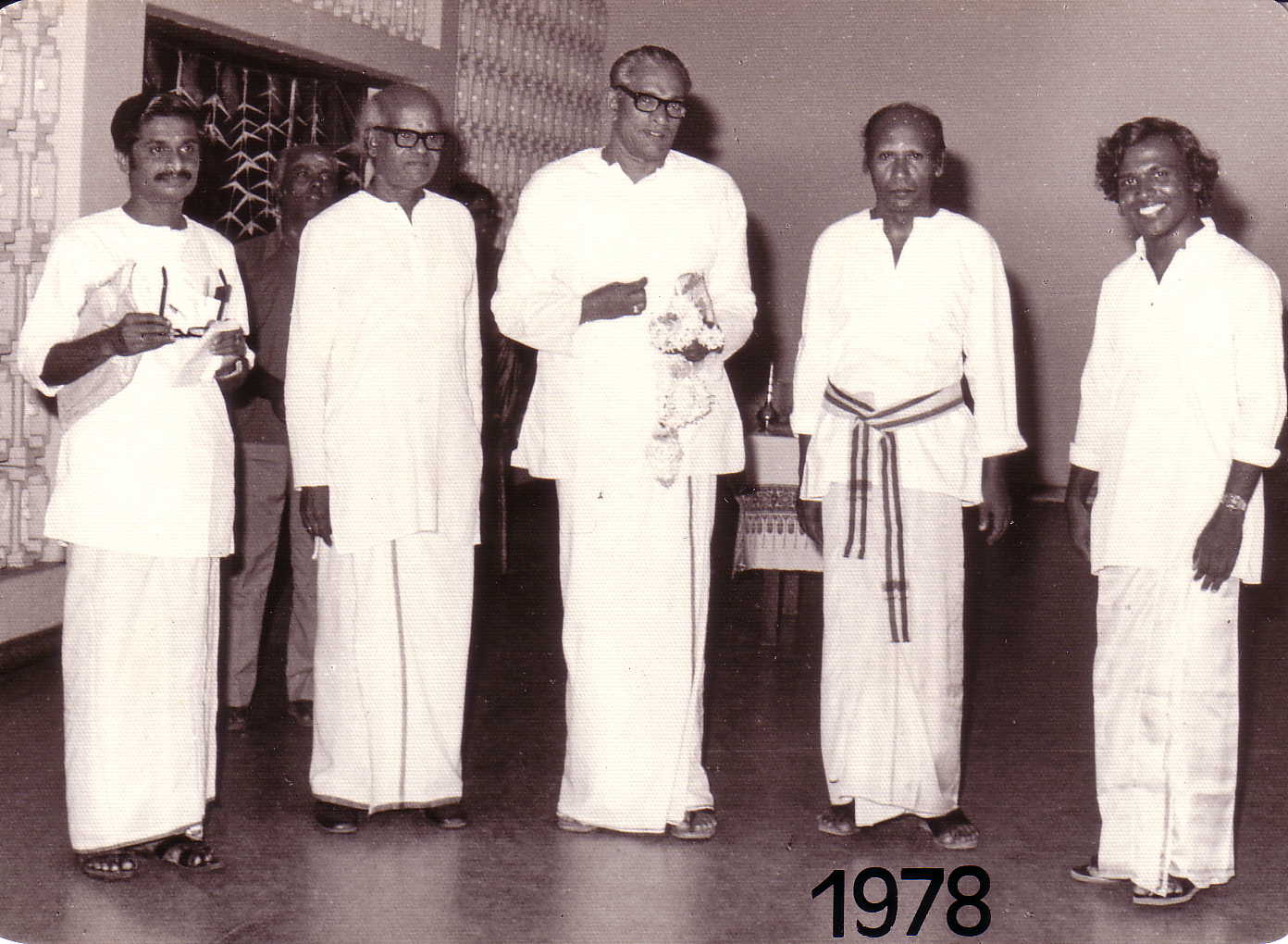

Sivapiragasam Sachithanantham, my father, was the last born among six siblings. The age difference between his eldest sister (first born) was 17 years. Though he was not a published writer, he supported my efforts to become a bilingual writer in Tamil and English wholeheartedly. One of the happiest days in his life was when I released my first Tamil book, Tamil Isai Theepam in August 1978 at Colombo, 35 years ago. Mr. Murugesu Sivasithamparam (then President of TULF) was the chief guest on that occasion. I provide a photo taken on that occasion nearby. Mr. Sivasithamparam is seen in the center. My father was standing to the left of Mr. Sivasithamparam. I’m standing to the left of my father. Mr. M.K. Eelaventhan (then the President of TULF – Colombo branch) is seen on extreme left. The gentleman standing between Mr. Eelaventhan and Mr. Sivasithamparam was Mr. Thenpuloliyur M. Kanapathipillai, traditional Tamil scholar.

My father wrote this ethnological vignette that I requested from him in Tamil language. I have translated it verbatim into English, in 2,435 words. Here it is.

Autobiographical Snippets (1923 – 1936)

by Siva Sachithanantham

My birth in Paruthi Thurai (Point Pedro)

I was born at our house Packiya Vasa to Vinasithambi Sivapragasam and Packiyam [nee Kanapathipillai] as the sixth and last child in August 13, 1923 on a Monday morning 8:15 am. Our house is located in Vadamarachchi region of Jaffna, at the Thumpalai section of the Point Pedro town. I had two elder sisters and three elder brothers. Our house was one of the three stone-based houses (kal-veedu) of that era, built by my maternal grandfather Kanapathipillai and given as dowry to my mother.

When I was born, there was no government hospital in Point Pedro. Near the sea beach, there was a dispensary which was manned by an apothecary. This apothecary offered the elementary medical service to patients and also to the travelers who landed at the Point Pedro port. He functioned as a quarantine officer, checking on the travelers for any infectious diseases. Then, only the sail ships plying from Tuticorin (south India) brought onion, chilli, arecanut and other food stuffs. Sail ships from Trincomalee region (Kotiyaram and Thambalakamam) brought paddy and hay to Point Pedro port.

When I was born, for child birth, those who could afford attended the Manipay or Inuvil hospitals which had better facilities. They traveled the distance of 18-20 miles on bucky cart, since cars were rare in our region then. These hospitals were managed by the Protestant Missionary services and one had to pay for the services. Thus, most of the families had their childbirth at home. Elderly ladies who had first-hand experience assisted the expectant mothers at home. During that colonial era of British, one never had nurses or midwifes in our locale. Thus, I was born at home.

There was no Registrar of Birth or Death as well. The father of the child should inform the new birth to the Village Headman (Vithanai). The same procedure held to the death as well. But, deaths in the community came to the attention of Village Headman easily, because the message was announced in the neighborhood by the characteristic moanful drum beats of drum professional (Paraiyar) caste. That was the tradition then. But, if a child was born, even the adjacent neighbors may be unaware of the event. The mother who had given birth would be given hot-water bath, enriched with the plucked leaves of Nochchi (Vitex species), Ada-thodai (Adhathoda zeylanica) and Vembu (Margossa, Azadirachta indica) trees for ten days following birth by the kin. This is believed to provide soothing effect for the body taxed by childbirth.

Father Sivapragasam

I learnt that my father was a businessman who kept himself busy at the time of my birth. He purchased items like tobacco leaf, processed palmyra products, and dry fish in the locality and transported these to Anuradhapura. Thus, during the time of my birth, he was more preoccupied with his calling, than informing my birth to the Village Headman. Of course, the village headman Mr. Paramu, was a pal of my father. Thus, two weeks after my birth, my father visited with Mr. Paramu and made the announcement. This resulted in my date of birth being officially recorded as August 28, 1923. Though one had to pay fine for the late announcement in child birth, since my father was a pal of the Village Headman, such a fine was easily passed off. Ah! those were the days when good friendship could even alter official records of birth and death!

My father Vinasithambi Sivapragasam should have been born in 1882. He died on September 12, 1936, at the age of 54. I was then 13 year old, and was a 5th grade student at the Hartley College. My father had four siblings: 3 males and one female. His eldest brother’s name was Sithamparapillai (nick name Sinnappa). The second elder brother was Sathasivampillai (nick name Sinnathurai). The third in the rank was a woman, whose name I cannot remember. Then, my father was the 4th in line. His youngest brother was Sivagnanasuntharam.

Since I was the last born in my family, I was treated as a ‘baby’. The age gap between me and my eldest sister was 17 years. I was called Sachi by the home folks. Later only, I realized that our household was down on luck at the time of my birth. Though he was a well-respected businessman, at the time of my birth, father had been pushed from riches to rags. Due to the burden and such suffering, he had taken to drinking palmyra toddy (kallu) and even taken the moniker ‘drunkard Sivapragasam’.

Mother Packiyam

My mother Packiyam Kanapathipillai should have been born in 1887. She died in May 25, 1945, when I was 22 years old. She lived for 58 years. My mother had five siblings: two elder brothers, two elder sisters and a younger brother. My mother was the fifth born. There is an old-saying in Tamil ‘Einthaam kaal Penn pillai Kenjavum kidaiyaathu’ [i.e., the fifth born female is a blessing rarely received]. So, she was treated as a real pet girl.

She had lost her mother when she was young, and her father Neelar Kanapathipillai remarried. Nevertheless, when she was young, my mother was more or less bathed in riches, since her father – my maternal grandfather – was known in the locale as luxurious Kanapathiyar [Panakkara kal-veedu Kanapathiyar] and was an influential person. In the early years of 20th century, there was not even a single house built on stone in our locale. All houses were raised on mud with palmyra leaves as the hood. My maternal grandfather was the first in that region to build three houses built on stone, with lime-based tiles.

The word ‘stone’ refers to the process of first collecting the sea shells from the sea shore, and burning the lime to ashes; the resulting ashes were then mixed with stones to raise the walls of the house. It would have been so expensive to build such a ‘stone’ house. Neelar Kanapathipillai built three such houses and offered them as dowry houses to his three daughters. His three sons were employed in colonial government service. The first son Kulanthaivelu was a postmaster. The second son Muthusamy was a government surveyor. The third son Ramasamy was a telecommunication inspector. Thus, my mother was a proud rich young lady, at the time of her marriage to my father. Though quite a number of marriage proposals were offered to her, ultimately my father was taken as the bridegroom. This should have been around 1904 or 1905, because my father had established his name as a well-known businessman who dealt with Kanipuram silk sarees and Tuticorin arecanuts as his merchandise. Thus, I later heard that in the early years of my parents’ married life, father used to bring home coins in multiple sacks. My mother was illiterate, and for the young kin who visit my house, mother handed coins in bounty without even counting them. The chief beneficiaries of mother’s munificence were Sivagnanasuntharam (father’s younger brother) and Ramasamy (mother’s younger brother) – both of whom were high school students and buddies. It was such a misfortune that mother who lived a luxurious life in her young days, had to do odd jobs to keep the family fire burning, by the time I was born.

Early School Days

I went to school at the age of 6, in 1929. The primary school in our neighborhood was Maathanai Mixed School. The word ‘Mixed’ referred to the connotation ‘students of both sexes’. It was basically a rectangular cottage, without separate classrooms or doors. The ‘building’ of the cottage was formed by half-sized walls made by clay mud. Each one of us had a slate and a slate-pencil. We also had palmyra-palm leaves, on one side of which Tamil alphabets were written and the opposite side had numbers 1,2, 3 and so on. I never had a shirt or vest – just bare bodied – or slippers to wear. What I wore was a folded salvai (shawl, which is usually worn by adult Tamils to cover the upper body) in the waist. That primary school had up to four grades. Only the students in the 3rd and 4th grades could sit in benches. Those students in the pre-1st grade, 1st grade and 2nd grade had to sit in the floor. The floor was made of hand-polished clay mud. There were three teachers; two men and one woman. The head teacher and his wife constituted the main personnel of the school, and the third individual was a kin of theirs. We addressed the head teacher as Saddambi [literal meaning, the law maker] and his wife as Thaiyal Amma [Sawing Lady]. This school was run by the Christian Mission folks. It began at 9 am and closed at 1 pm.

In the pre-1st grade, we sat in a circle with Thaiyal Amma in the center and wrote Tamil alphabets in the sand, while reciting them loudly by mouth. We also listened to short stories told by our woman teacher. In the first grade, we learnt to write the Tamil alphabets in the slate. In the second grade, we were introduced to reading the book. In the third grade, we began writing with pencil. In the fourth grade, we had to learn writing with the pen, dipped in ink bottle. We also had to memorize the multiplication table up to 12. Once an year, ‘the inspector’ will pay a visit, and after he conducts his testing only, we were promoted. The promotion occurred only after the somewhat ‘scary’ visit of the inspector. He usually paid his visit between January and April of the year.

In those days, we never had regularized ‘holiday’ time in school. If there was a heavy rain or if there were annual festivals of the neighborhood temples, we had school holidays. If we failed to attend the school consecutively for 3 or 4 days, the head teacher would visit our house. This was because, if the attendance roster of children showed a dip, the school funding from the Missionary circle would receive a cut.

Hartley College

When I was 10 (in 1933), I joined the Hartley College. My preference was to join the Velayuthan Puloly Boys Hindu School, which was nearby to our house. The main reason for me was that, if I joined the Velayuthan School, I could return home during lunch time to have something to eat. But my three elder brothers were then studying at the Hartley College – so I was forced to join there. One of our elderly kin Mr. Sampanthar was a teacher at Hartley College then. In those days, the school fee for one student was Two rupees and 50 cents. Since three of my elder brothers studied at the same time, for our eldest brother (Pathmanathan) we paid two rupees. For the second elder brother (Vaikunthanathan), it cost one rupee and 50 cents; and for the third elder brother (Surendiranathan) it cost one rupee. But, I had it free. The year I joined Hartley College, my eldest brother passed the London Matriculation Exam and left the school. I has in Hartley College from 1933 to 1941.

The Misfortune

I still remember that my mother said often, that from the year of second elder brother Vaikunthanathan’s birth (i.e., 1916), the disastrous Raghu period began and four well- nourished cows we had with us died one after another. ‘This Raghu period, lasting for the next 18 years (until 1934), had shredded the family wealth to ashes’. The biggest misfortune which fell on our household occurred probably around 1932. The smoked tobacco leaf bundles which were one of the main items of my father’s business were routinely transported from Kodikamam to Anuradhapura, by coal-locomotive train coaches (kari-koachi, in Tamil), then plying the Northern route. Two car compartments of the train coach usually carried father’s smoked tobacco leaves in bundles. One day, flinders of burning coal, due to heavy wind, landed in the car compartments filled with father’s smoked tobacco leaf bundles and led to disaster. That particular train caught fire and all the car compartments turned into ashes. This resulted in an irretrievable loss of estimated 10,000 rupees [This unimaginable figure was in 1932, which could amount to hundreds of thousands of rupees now in 2002.] worth capital for my father. When compensation claim was petitioned by my father, the colonial government had bullied him with a smirk response: ‘It’s because of your smoked tobacco leaf bundles, we had to lose 16 car compartments of the train. So, how can we pay compensation for you?’ My father couldn’t recover from this heavy loss of capital.

Father’s Final Days

I was aged 13 then. My father used to walk to Kudathanai and Manal Kaadu regions to collect items for his struggling business. If he left the house, it would take two or three days for him to return. Once, he returned after such a trip and lied down on a mat. Due to persistent worries and depression, he used to eat only once a day – usually at nights. On that particular Friday night, he just drank ‘plain’ tea. He had high fever as well. Mother sent word for our neighbor Sinnaiah pariyari (traditional physician). He was a good buddy of my father, since both enjoyed kallu liquor regularly. When physician Sinnaiah came (not in a sober state, of course!), he took hold of father’s hand and checked his pulses. Realizing the precarious state of his buddy’s health, Sinnaiah cried instinctly, ‘Sivapragasam – ennai viddu poha poriya?’ [Are you going to leave me, Sivapragasam?] and left our house without any word for us. Late in that night, around 1 o’clock, father woke up my mother and sobbed, ‘Naan poha pohiraen. Pillaikalai kondu paalai paruku’ [I’m leaving you all. Let children offer milk to my mouth.]. Then, we had only a ‘hurricane’ lamp and two small pot lamps at hour house. Our mother woke all of us who were sleeping nearby in the mats, and each of us placed a spoon of milk in his mouth. After hearing the news, neighbors also came running to watch. By 2:30 am, father slumpered again.

Since the following day was a Saturday, we didn’t have school. We were at home. Neighbors again came visiting. Father’s buddy Sinnaiah pariyari returned again and checked father’s pulse. He quipped: ‘Hmm! Weak pulse; and the next 12 hours we should wait to see what happens.’ Then, he left. Father talked with us softly and did hum thevaram hymns. By 12 noon, he said, ‘Ennavo seyyuthu’ [Something unpleasant is being felt.] and closed his eyes. That was it. Only a week prior to our father’s death, my eldest brother Pathmanathan received his first job appointment as a teacher for Nainativu Hindu school.

Post-script by Sachi: Probably for space consideration, M.K.Eelaventhan (standing on extreme left) of the photo had been unfortunately clipped off. You could also notice that Mr. M. Sivasithamparam carries a copy of my book in his left hand with the garland.

Post-script (2) Dec. 4: The editor had let me know, that the entire photo (including M.K.Eelaventhan) had been restored back.

Thank you for sharing