40th Anniversary of January 10th Deaths in Jaffna and De Kretser Commission Findings

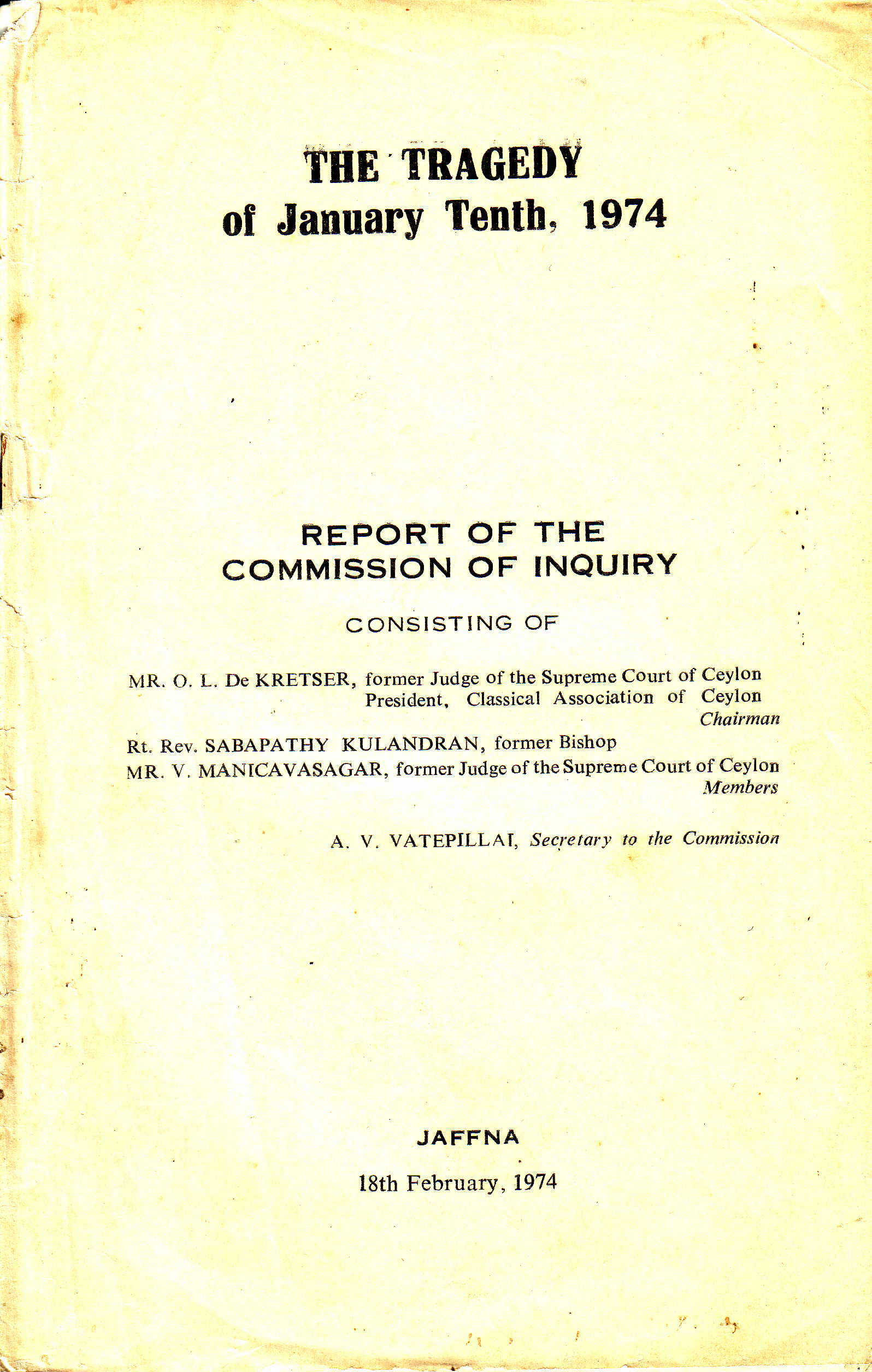

Jaffna Conference 1974 Tragedy committee report

The Fourth International Conference of Tamil Research Studies was held in Jaffna, between January 3rd and 9th, 1974. Unfortunately, on the next day (January 10th), a tragedy occurred and nine individuals lost their lives among the approximately 50,000 folks who had gathered to listen to Professor Naina Mohamed. As one would expect that the then ruling party headed by Mrs. Sirimavo Bandaranaike and her Tamil sycophants (such as C. Kumarasooriyar – the Minister of Post and Telecommunications, Alfred Duraiappah – the ex-MP for Jaffna and some Tamil academics who promoted themselves as ‘Progressives’) were uninterested in holding an inquiry of that tragedy.

As such, the Citizen’s Committee of Jaffna, appointed a three men committee that consisted of Mr. O.L. De Kretser Jr. (Chairman), Rev. Sabapathy Kulandran and Mr. V. Manickavasagar to inquire that tragedy. This Commission held sittings at Palm Court, Jaffna on 2nd, 4th, 5th, 12th and 13th of February, 1974 and issued its Report on February 18, 1974. The report was published in March 1974, on behalf of Citizen’s Committee of Jaffna. Dr. V.T.Pasupati functioned as its chairman, and V. Yogeswaran (later to be elected as an MP for Jaffna in 1977) was its secretary.

For electronic record, I provide a PDF file of this De Kretser Commission Inquiry Report in its entirety. It has been in my personal collection. Here are the four salient conclusions of this Inquiry Report.

Conclusion 1: “The irresistible conclusion we come to is that the police on this night was guilty of a violent and quite an unnecessary attack on unarmed citizens. We are gravely concerned that they lacked the judgement which we expect of policemen in a civilian force whose duties call for tactful handling even in the most difficult situation.”

Conclusion 2: “The evidence establishes that this was not all that took place that night. The police in their armed might roved the city assaulting whomsoever they came across for no better reason than that the people were doing what they were entitled to do.”

Conclusion 3: “We are of opinion that those who suffered physical injury and material damage, and those who lost their lives were the innocent victims of a chain of events set in motion by a completely wrong and unwise decision on the part of the police officer who made it.”

Conclusion 4: “We can find no justification at all for the police assault on defenceless and innocent citizens; indeed there can be no justification for the police to use force, save in the exceptional circumstance of defending person and property, and that too the bare minimum; for it is not the function of the police to punish wrong doers, for that is a function of the courts of law.”

Differing from Rajan Hoole’s Version of Events

It is of consequence that this particular tragedy had its boomerang effect on the activities of Eelam Tamil militancy. If I have to tag who the ranking culprits were, I’ll mention the following,

(1) Mr. S.K. Chandrasekera, the Assistant Superintendent of Police, Jaffna.

(2) Mrs. Srimavo Bandaranaike, the then Prime Minister

(3) Mr. C. Kumarasuriyar, the then Minister of Posts and Telecommunications

(4) Mr. Badiuddin Mahmud, the then Minister of Education

(5) Mr. Alfred Duraiappah, the sycophant to the Prime Minister and the Mayor of Jaffna.

The first one was the immediate culprit. The other four aided and abetted the crime actively (by virtue of their political positions) via their ‘un-promotional stance and activities’ of not wanting to have Jaffna as the venue for the Conference. It is my view that the entire political context in which the Fourth International Tamil Conference was ‘un-promoted’ deserves to be looked at. Those who contributed to this ‘un-promotion’ overtly and covertly had to be tagged as culprits.

In this culprit ranking, I differ from the views expressed by Rajan Hoole’s revisionist pro-SLFP and pro-Duraiappah version, expressed in his book, ‘Sri Lanka: The Arrogance of Power Myths, Decadence & Murder’ (2001). This version has some noticeable factual defects. I quote one specific paragraph from this book.

“The organisers had earlier planned to hold the final meeting in the open-air theatre for which authorization had been obtained from the Jaffna mayor, Mr. Duraiappah. But because there had been a shower on the 9th, the organisers decided to shift the final meeting to the Veerasingham Hall. But on the 10th the crowds started squeezing into the Hall and many had to be content listening from outside. Seeing there was no rain, the organisers at the last minute decided to go back to the open air theatre. They tried to contact the mayor (Duraiappah) and the municipal commissioner to gain access to the theatre, but were unsuccessful.”

The last sentence in this paragraph seems interesting. Why the conference organisers couldn’t contact Duraiappah, the Mayor of Jaffna? Was he out of town, on vacation or on health grounds? A significant event was happening for a week in Jaffna, and the Mayor (not to be seen within town and couldn’t be available for permission requests) was a scenario that could be interpreted about his split loyalties to the ruling SLFP party and not to the Tamil public he served. Duraiappah played his game of ‘run with the rabbits and hunt with the hounds’ to his detriment.

While checking for details on the career of police chief S.K. Chandrasekera, I came across the following garbled version offered by Gamini Gunawardene, a retired senior DIG of Police in 2010.

“Another outcome of the new Constitution [relating to the 1972 Republican Constitution] was that the Tamil members of parliament boycotted the Constituent Assembly adopting the Vadukoddai Resolution of 1976 for a separate state. This move finally ended up in the emergence of the Tamil terrorist movement following the JVP model. Early investigations by the CID had the first 43 terrorists in custody when the government decided to release them at the request of Alfred Duraiappah, looking for political advantage for the party in power over the Federal Party at the KKS [Kankesanthurai] by-election. The immediate result was the murder of Duraiappah himself. This was followed [emphasis by Sachi] by the deaths of several Tamil persons and two police officers by electrocution at a hot political meeting [emphasis by Sachi] at the Veerasingham Hall.

This was politically interpreted as a deliberate act of the government through the Jaffna police which was headed by S.K. Chandrasekera, SP. It was made out that Chandrasekera who was earlier the chief of the security of Mrs. Bandaranaike was specially chosen and sent there to harass the Tamils. In fact, Chandrasekera was removed from his position for some misdemeanor on his part and posted to Jaffna on punishment.”

Pooh! Gamini Gunawardane, the retired senior DIG of police, had re-written the history in a time-reversal mode! Chronologically, the Tamil Conference [in which so many international scholars with no political affiliation participated, had been twisted into ‘hot political meeting’] was held in January 1974. Kankesanthurai by-election was held in February 1975. Alfred Duraiappah was assassinated in July 1975. One cannot blame poor Mr. Gunawardane for such distortions, because police folks in Sri Lanka were/are poorly trained to such academic rigidity relating to time sequences of historical events.

Rajan Hoole also had cast aspersions on the partiality of one of the Commissioners, as follows: “Bishop Kulandran who was on the Commission was known for his leanings towards the Federal Party (TUF).” But, he had conveniently ignored the fact that even the chairman of the Commission, Justice O.L. de Kretzer (a member of the minority Burgher community) that he was the District judge in the famous C. Kodeeswaran’s Constitutional infringement case of 1962 (Kodeeswaran vs Attorney General), where de Kretzer upheld the plea of Kodeeswaran and ruled that the Official Language Act and the regulation was ultra vires and contravened Section 29 of the Constitution of Ceylon. Furthermore, in attempting to defend the lackluster political career of Duraiappah since 1965 (after he was defeated in the general elections of 1965 and 1970), Rajan Hoole cavalierly dismisses Duraiappah’s role in Mrs. Bandaranaike postponing the Kankesanthurai by-election for more than two years (1973 and 1974).

I did check some other books which appeared since 1980 to see how this January 10th 1974 tragedy is covered. Historian K.M. de Silva makes no specific mention of this tragedy in his ‘A History of Sri Lanka’ (1981). But, chapter 38 of his book entitled ‘Sri Lanka, 1970-1977: democracy at bay (pp.540-556) is vital to comprehend the entire context in which the Conference in Jaffna was ‘un-promoted’. It also includes specific mention of the role played by Mr. Badiuddin Mahmud, as the Minister of Education, in antagonizing the young Tamils. Rajan Hoole had failed to comprehend this fact.

In his first book ‘The Broken Palmyra’ (1990 revised version), Rajan Hoole mentions the tragedy only in three sentences, as follows.

“An event which had considerable impact on Tamil political thought was the police attack on the International Tamil Research Conference hosted in Jaffna in January 1974. Nine persons died by accidental electrocution during this unprovoked attack, which took place in the presence of international scholars. It was a measure of Mrs. Bandaranaike’s arrogance that she refused to order an inquiry.”

Better descriptions appeared later from T. Sabaratnam, in his ‘The Murder of a Moderate – Political Biography of Appapillai Amirthalingam’ (1996) and S. Sivanayagam, in his ‘Sri Lanka – Witness to History; a Journalist’s Memoirs 1930-2004’ (2005).

The Fates of Culprits

Chelliah Kumarasuriyar

In his 1996 book, T. Sabaratnam had reminisced about the role played by C.Kumarasuriyar as follows,

“The [Tamil] youth were wild with anger. They blamed the government as engineering the police attack. Their anger was directed against the then Post and Telecommunications Minister C. Kumarasuriyar because he had opposed the holding of the conference in Jaffna. Kumarasuriyar had charged that it was a TUF [Tamil United Front, the progenitor of TULF] show and was an anti-government nature. I was in the organizing committee and became a victim of Kumarasuriyar’s wrath. He complained to the Lake House management, which the government had taken over in July 1973, that I was a TUF supporter and was giving it undue publicity in the Tamil daily Thinakaran in which I worked. He also told the Prime Minister that the research conference was a TUF publicity stunt. I was forced to resign from the organizing committee.” (p.231)

The same Kumarasuriyar then lived to see the net-worth of his sycophancy to Sinhalese politicians in the 1983 anti-Tamil riots in Colombo. He was mauled by a Sinhalese mob, despite his claims to the mob that he was a former minister in the Sirimavo Bandaranaike Cabinet. This tragic episode had been described by Rajan Hoole in his 2001 book, and I refrain from reproducing it here, as it is available in the internet.

Alfred Duraiappah and Srimavo Bandaranaike

As all know, Alfred Duraiappah paid with his life in 1975, for his services as a supreme sycophant and pimp for the Colombo regime’s mother-son duo. Srimavo Bandaranaike was defeated badly in the 1977 general election and in the 1988 presidential election. When she was appointed as prime minister in 1994 by her daughter Chandrika after 17 years, she was visibly aged, merely a skeleton of her old self and doddered along until her natural death in 2000.

For a good version on the roles played by Mrs. Bandaranaike and Duraiappah, I provide the details offered by journalist S.Sivanayagam, in his memoirs.

“Prime Minister, Mrs. Bandaranaike, was already busy snipping off all cultural links with Tamil Nadu by banning the import of Indian films, Indian books and magazines, and making Tamil pilgrim travel to India virtually impossible. The IATR[International Association for Tamil Research] announcement of holding an international Tamil conference in Sri Lanka was certainly unwelcome news to her, but at the same time the Sri Lankan government could not be seen as opposing it. Mrs. Bandaranaike’s strategy was to contain any euphoria that the conference could evoke; to that purpose, she offered the Bandaranaike Memorial International Conference Hall (BMICH) in Colombo as the venue for the conference, and whatever other assistance that was needed. But this was summarily rejected by the conveners who insisted that it was but logical that a conference involving Tamil studies to be held in a Tamil milieu among a Tamil-speaking population. The Srimavo Bandaranaike government showed its small-mindedness by delaying visas to several international scholars until three days before the conference and refusing visas to some Tamil activists from India. While on the one hand the government openly adopted a hostile position, the behavior of some of the leading promoters of the Conference did not smooth matters either…

The conference, attended by Tamil scholars from many parts of the world was held at Veerasingham Hall, Jaffna from 3 to 10 January 1974. The entire Jaffna town wore a festive air during that week. In a country where the Tamil language was denied any official recognition, and where the Tamil people were themselves groaning under state oppression, what was undoubtedly the greatest international conference held in Jaffna was marred by tragedy on the final day. If the government in Colombo was antagonistic, the authorities in Jaffna were no less. Jaffna had a mayor in Alfred Duraiappah, a Tamil himself but who was a henchman of the government, whose initial reluctance to permit the use of the open air theatre angered the people. Jaffna also had a Sinhalese-dominated police force that was already earning the hatred of the people. What should have been a grand finale to the conference ended in scenes of bedlam and tragedy.”

Badiuddin Mahmud

Badiuddin Mahmud, after antagonizing the Tamil students with the notorious ‘standardization policy in 1970, and practicing patronage politics to employ more Muslims as teachers in public schools to the detriment of Tamil teachers for 7 years, without having the guts to stand in election at a Sinhalese electorate, attempted to enter the parliament via then Batticaloa constituency (electing 2 members). He failed in this attempt too. He had a natural death in 1997. As I have mentioned earlier, Prof. K.M.de Silva had provided some context to this Muslim politician’s role during 1970-1977.

S.K. Chandrasekera

Assistant Superintendent of Police S.K. Chandrasekera (born 1921) received a promotion for his services to the Sinhalese State, during the Sirimavo Bandaranaike regime. He joined the police service on 1949 July 1, and was promoted to Assistant Superintendent of Police rank on 1966 October 1; then on 1973 June 2, he was promoted to Assistant Superintendent of Police, Grade II rank.

Additional Sources

Parliamentary Debates (Hansard) Official Report, January 5, 1979, vol.4, no.2. This source provides the details of Acting appoints and promotions in Police Service, as of July 23, 1977.

Gamini Gunawardane: Stanley Senanayake Saga in the Police: some random sketches of events in contemporary history. The Island (Colombo), Dec.18, 2010.