by Sachi Sri Kantha, March 27, 2015

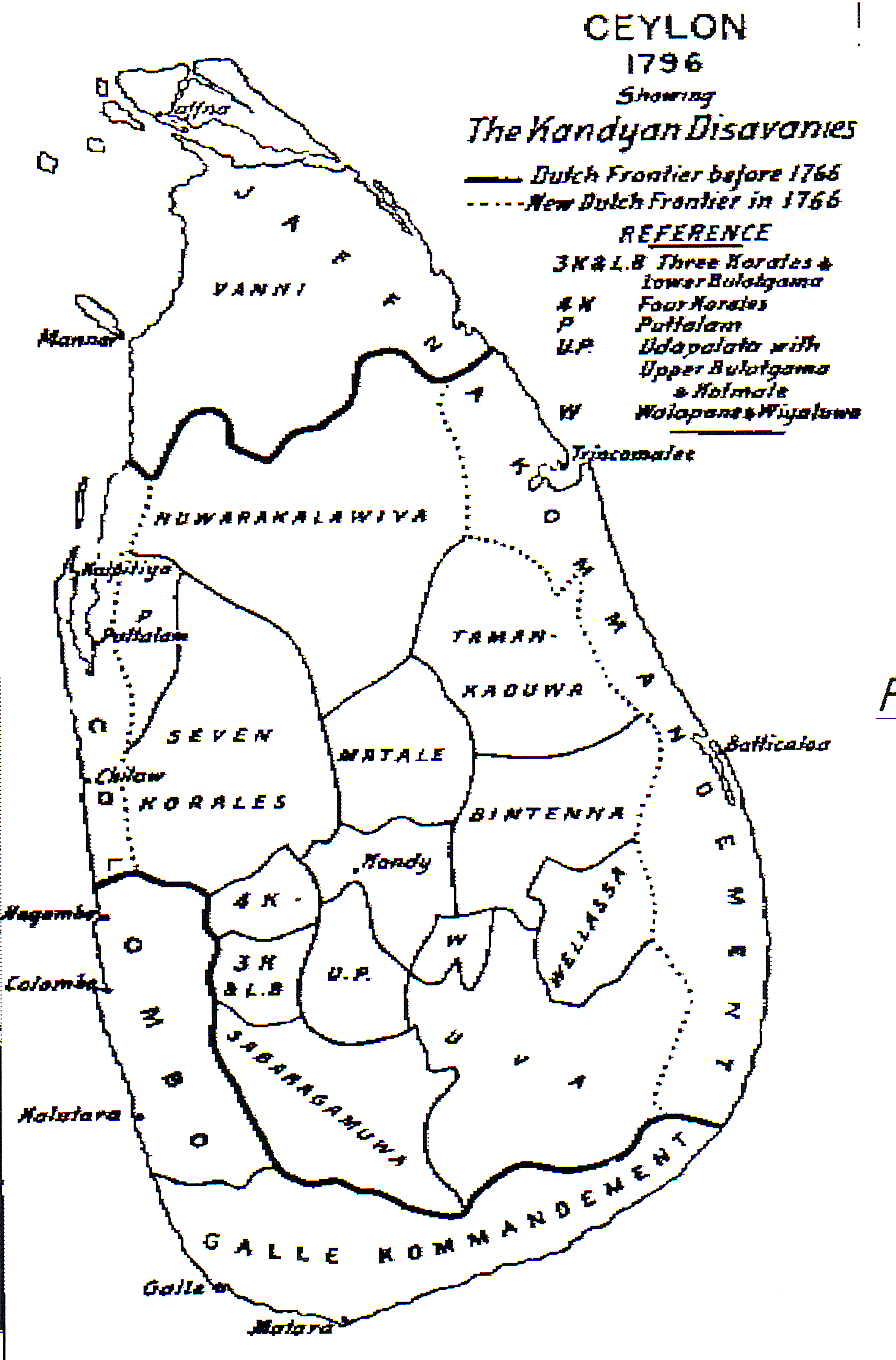

March 2, 1815 marked the 200th anniversary of the British annexation of the Kandyan Kingdom of Ceylon. To reminisce on the significance of this imperialistic annexation by the British colonial strategists, first I provide below the observations made by a few notable historians, such as Sir James Emerson Tennent (1859), Sir Ponnambalam Arunachalam (1906), Sir Charles Jeffries (1962), G.C. Mendis and S.A. Pakeman (1962), and Paul M. Jayarajan (1976?). Then, I make some specific comments related to this anniversary.

Sir James Emerson Tennent (1859)

Emerson Tennent (1804-1869) served as the British colonial secretary of Ceylon in the second half of 1840s. He is recognized for his 1859 monograph on Ceylon, published in the same year as that of Charles Darwin’s classic ‘The Origin of Species’. Covering the period from 1803 to 1814, Tennent offers the following description. I provide Tennent’s description in full here, because one can see parallels with how British journalists including those who were reporting to the Economist magazine in the recent times painted LTTE and its leader Velupillai Prabhakaran with the same tone, without verifying the in-depth details.

“The career of the Kandyan king presents a picture of tyrannous atrocity unsurpassed, if it be even paralleled, in its savage excesses, by any recorded example of human depravity. Distracted between the sense of possessing regal power and the consciousness of inability to wield it, he was at once tryrannous and timid, suspicious and revengeful. Insurrections were excited by his cruelties, and the chiefs who remained loyal became odious from possessing the influence to suppress them. The forced labour of the people was expended on works of caprice and inutility; and the courtiers who ventured to remonstrate were dismissed and exiled to their estates. At length, the often-baffled traitor, Pilame Talawe, was detected in an attempt to assassinate the king, and beheaded in 1812, and his nephew, Eheylapola, raised to the office of Adigar.

But Eheylapola inherited with the power all the ambitious duplicity of his predecessor; and availing himself of the universal horror with which the king was regarded, he secretly solicited the connivance of the Governor, Sir Robert Brownrigg, to the organization of a general revolt. The conspiracy was discovered and extinguished with indiscriminate bloodshed; whilst the discomfited Adigar was forced to fly to Colombo, and supplicate the protection of the British. And now followed an awful tragedy, which cannot be more vividly described than in the language of Davy, who collected the particulars from eye-witnesses of the scene. ‘Hurried along by the flood of his revenge, the tyrant, lost to every tender feeling, resolved to punish Eheylapola who had escaped, through his family, who still remained in his power: he sentenced his wife and children, and his brother and his wife, to death; the brother and children to be beheaded, and the females to be drowned. In front of the queen’s palace, and between the Nata and Maha Vishnu Dewales, as if to shock and insult the gods as well as the sex, the wife of Eheylapola and his children were brought from prison, where they had been in charge of female gaolers, and delivered over to the executioners. The lady, with great resolution, maintained hers and her children’s innocence and her lord’s; at the same time, submitting to the king’s pleasure, and offering up her own and her offspring’s lives, with the fervent hope that he husband would be benefited by the sacrifice. Having uttered these sentiments aloud, she desired her eldest child to submit to his fate; the poor boy, who was eleven years old, clung to his mother terrified and crying; her second son, of nine years, heroically stepped forward; and bade his brother not to be afraid – he would show him the way to die! By the blow of a sword the head of this noble child was severed from his body: streaming with blood, and hardly inanimate, it was thrown into a rice mortar, the pestle was put into the mother’s hands, and she was ordered to pound it, or be disgracefully tortured. To avoid the infamy, the wretched woman did lift up the pestle and let it fall. One by one the heads of her children were cut off; and one by one the poor mother… [Note by Sachi: dots, as in the original] but the circumstance is too dreadful to be dwelt on. One of the children was an infant, and it was plucked from its mother’s breast to be beheaded: when the head was severed from the body, the milk it had just drawn ran out mingled with its blood. During this tragical scene, the crowd who had assembled to witness it wept and sobbed aloud, unable to suppress their feelings of grief and horror. Palihapane Dissave was so affected that he fainted, and was expelled his office for showing such sensibility. During two days, the whole of Kandy, with the exception of the tyrant’s court, was as one house of mourning and lamentation, and so deep was the grief that not a fire, it is said, was kindled, no food was dressed, and a general fast was held. After the execution of her children, the sufferings of the mother were speedily relieved. She and her sister-in-law were led to the little tank in the immediate neighborhood of Kandy, called Bogambara, and drowned.

This awful occurrence in all its hideous particulars, I have had verified by individuals still living, who were spectators of a scene that, after the lapse of forty years, is still spoken of with a shudder.

But the limit of human endurance had been passed: revolt became rife throughout the kingdom: promiscuous executions followed, and the terrified nation anxiously watched for the approach of a British force to rescue them from the monster on the throne. At length, the insensate savage ventured to challenge the descent of the vengeance that awaited him. A party of native merchants, British subjects, who had gone up to Kandy to trade, were seized and mutilated by the tyrant; they were deprived of their ears, their noses, and hands, and those who survived were driven towards Colombo, with the severed members tied to their necks.”

Then, about the events in 1815, Tennent offers the following description:

“An avenging army was instantly on its march. War was declared in January 1815, and within a few weeks the Kandyan capital was once more in the possession of the English, and the despot a captive at Colombo whence he was eventually transferred to the Indian fortress of Vellore. The proclamation of the Viceroy recalled the massacre of 1803 as one of the many causes of the war, and on the 2nd March 1815, a solemn convention of the chiefs assembled in the audience hall of the palace of Kandy, at which a treaty was concluded formally deposing the king and vesting his dominions in the British Crown; on condition that the national religion should be maintained and protected, justice impartially administered to the people, and the chiefs guaranteed in their ancient privileges and powers. Eheylapola, who had cherished the expectation that the crown would have descended to his own head, bore the disappointment with dignity, declined the offers of high office, and retired with the declaration that his ambition was satisfied by being recognized as ‘the Friend of the British Government.’ ”

Pon. Arunachalam (1906).

Sir Ponnambalam Arunachalam (1853-1924) was one of the leading Tamil intellectuals of his era, who distinguished himself as a politician, administrator and academic.

“In 1815 the British government declared war against the last king of Kandy. Mr. Sawers, who was the chief British official in Kandy from 1815 to 1827, says in his Notes on the Conquest of Kandy, ‘It has been frequently stated that the king had by his tyranny forfeited the loyalty and attachment of the great body of the people, but this imputation is not well-founded. His quarrels were with his chiefs and the chiefs alone; and perhaps the circumstance which particularly rendered him obnoxious to the hatred of the chiefs, was the disposition he evinced of a determination to protect the people from the oppression of the aristocracy.’ Their resentment made them cooperate with the British army and crippled his defence, and he was eventually taken prisoner.

The report of the capture reached the Governor and Commander-in-chief, General Brownrigg, while he was at dinner with a small party of officers. One of them thus describes the scene. ‘The intelligence being highly gratifying and in many respects of the utmost importance, His Excellency became greatly affected. He stood up at table and, while the tears rolled down his cheeks, shook hands with every one present, and thanked them for their exertions in furtherance of an object which seemed to be nearly accomplished and which had been vainly attempted for nearly three centuries by three European powers in succession – the conquest of the kingdom of Kandy’ (Marshall’s Ceylon, p. 158)

In terms of a convention held on 2nd March 1815, at Kandy, between the British authorities and the Kandyan chiefs, the kind was dethroned, and the Sinhalese voluntarily surrendered their island to the British sovereign with full reservation of their rights and liberties. They may thus claim to be one of the few ancient races of the world who have not been conquered. The Kandyan king was conveyed to Colombo and deported thence to Vellore in the Madras Presidency, where he died in 1832 of dropsy.

Thus ended the oldest dynasty in the world, after enduring for twenty-four centuries, and the whole island passed under the sway of Britain. A few years ago, at Tanjore in the Madras Presidency, I had the honor of being presented to the last surviving Queen of Kandy. In spite of straitened means she still maintained the traditions and ceremonial of a court. Speaking from behind a curtain, she was pleased to welcome me and to express her appreciation of some little services rendered to her family since their downfall. She has now passed away. A lineal descendant of the kings of Ceylon holds a minor clerkship in the Registrar-General’s Department of this island – a living testimony to the revolutions of the wheel of fortune.”

Sir Charles Jeffries (1962)

Sir Chalres Jeffries (1896-1972) was a British official.

“Lieutenant-General Sir Robert Brownrigg, who took over in 1812, is notable mainly for the fact that during his term of office the Kingdom of Kandy was annexed to the Crown, making it possible for Ceylon to develop as a single country. The British Government had no wish to annex the Kingdom, and public opinion would not have supported an aggressive policy. There was, however, continual friction between the ruler of Kandy and the colonial authorities, and all attempts at reaching a satisfactory modus vivendi proved abortive. The Kandyan Chiefs themselves were thoroughly disgruntled with the regime and pressed the British to take over. In January 1814, the Governor, justifying his action on the general ground of requests from the people of Kandy and on the particular ground of atrocities committed against British subjects, invaded the Kingdom with a strong army reinforced by detachments from India. He proclaimed to the people that he was doing this ‘for securing the permanent tranquility of these setllements and in vindication of the British name: for the deliverance of the Kandyan people from their oppressors’ and so forth; and he proffered to every Kandyan ‘the benign protection of the British Government’. The King was captured and deposed, and an Act of Settlement was entered into with the Chiefs and proclaimed on March 2, 1815.

The British Government, faced with this fait accompli, might well have felt some perturbation at the probably effect on public opinion of what could easily have been criticized as a flagrantly high-handed act of empire-building. As it happened, however, the news of the annexation reached London at the same time as that of the victory of Waterloo, and no one was disposed to bother about it.”

G.C. Mendis and S.A. Pakeman

Garett Champness Mendis (1893-1976) and Sidney Arnold Pakeman (1891- ?) are historians; while Mendis a Sri Lankan, Pakeman was a British national, who also served one term as an appointed member in the Ceylon Parliament from 1947 to 1952.

“The King of Kandy, Sri Vikrama Rajasingha, soon got to know that his chiefs, and not the British, were his real enemies. He then took a great deal of their power away from them. He gave the chief posts to his Nayakkar relations. He altered the arrangement of the districts and did not allow members of the old families to be chiefs. He tried to make the people friendly with him by punishing the chiefs who treated the people badly.

The chiefs of course were very angry with him. Pilimatalavve’s advice was no longer followed and so he tried to kill the King. But this was discovered in time and he was put to death in 1812.

Ahalepola then became First Adigar and the head of the chiefs who were against the King. He tried to get the help of the British as Pilimatalavve had done. Robert Brownwrigg, before he was sent to Ceylon to be the Governor, was told to be friendly to the King. He tried to make a treaty with the King but was not able to do it. Like North, he then began to think of conquering the Kandyan Kingdom. He sent messages to the chiefs who were not friendly to the King. When the King got to know what was going on, he punished Ahalepola and his friends and the people who helped him. Ahalepola then went to war against the King.

Whatever Pilimatalavve did, he did not wish to hand over the kingdom to the British. Therefore he did not try to get the help of the British after the war of 1803, but Ahalepola did not mind if the British ruled the Kingdom. He was only anxious to get rid of the King. The British did not want to have the same kind of defeat as they had the last time, and so they did not help Ahalepola in his war against the King. As a result, Ahalepola was defeated, and had to run away with his men for safety to the British.

One they had run away, the King punished very cruelly the families and relations of those who had fought against him. He even punished bhikshus who happened to be relations of those chiefs. One of them, who was very good and learned, was executed. Everyone was angry with the King for doing such things and both the chiefs and the Sangha turned against him.

Brownrigg then thought that he ought to do something. He knew that all the Kandyan chiefs wanted the British to take over the country. As he was sure they would be on his side, he made war on the King. The British army marched through Mattamagoda, Iddamalpana, Hettimulla, Attapitiya and Ganetanna without much difficulty, and took Kandy. The King, finding that all his chiefs were against him, escaped from Kandy but was caught near Teldeniya.

The British and the Kandyan chiefs then made a treaty called the Kandyan Convention. The chiefs agreed not to allow the Nayakkars to be Kings of Kandy, to make the British their rulers and to trade with the British.”

Paul Jayarajan (1976?)

“The deposition from the throne and the banishment of the last king of Kandy and the vesting of the dominions of the kingdom of Kandy in the British sovereign were effected by a proclamation of the Governor of Ceylon (popularly known as the Kandyan Convention) in 1815 which was written in English on one half of the pages and in Sinhala on the other. Now although the East Coast of India was well known at this time as the Coromandel Coast yet when the proclamation referred to the claim and title of the Malabar race to the dominion of the Kandy provinces and the expulsion of ‘all male persons of the Malabar Coast’ this could not be taken to mean the peoples of Kerala or of the West Coast of India. The king was not a Malayalee but a Tamil Nayakar from Madura. For some reason or other it was customary in Ceylon at that time and in the 18th century to refer to the Tamil language as the Malabar language and to the Tamils from Madurai or Tanjavur (Tanjore) as people of Malabar. Such references did not refer exclusively to the territory of Kerala. It may be that because of the use of the Grantha script in a mixed script with Tamil and of the close similarity in the Tamil and Malayalam languages, or because the Grantha script was regarded only as a sophisticated Tamil script, the British and Dutch referred to all those who came from the former Cera and Cola kingdoms as peoples of Malabar reserving the Coromandel Coast to mean the Andhra hinterland….

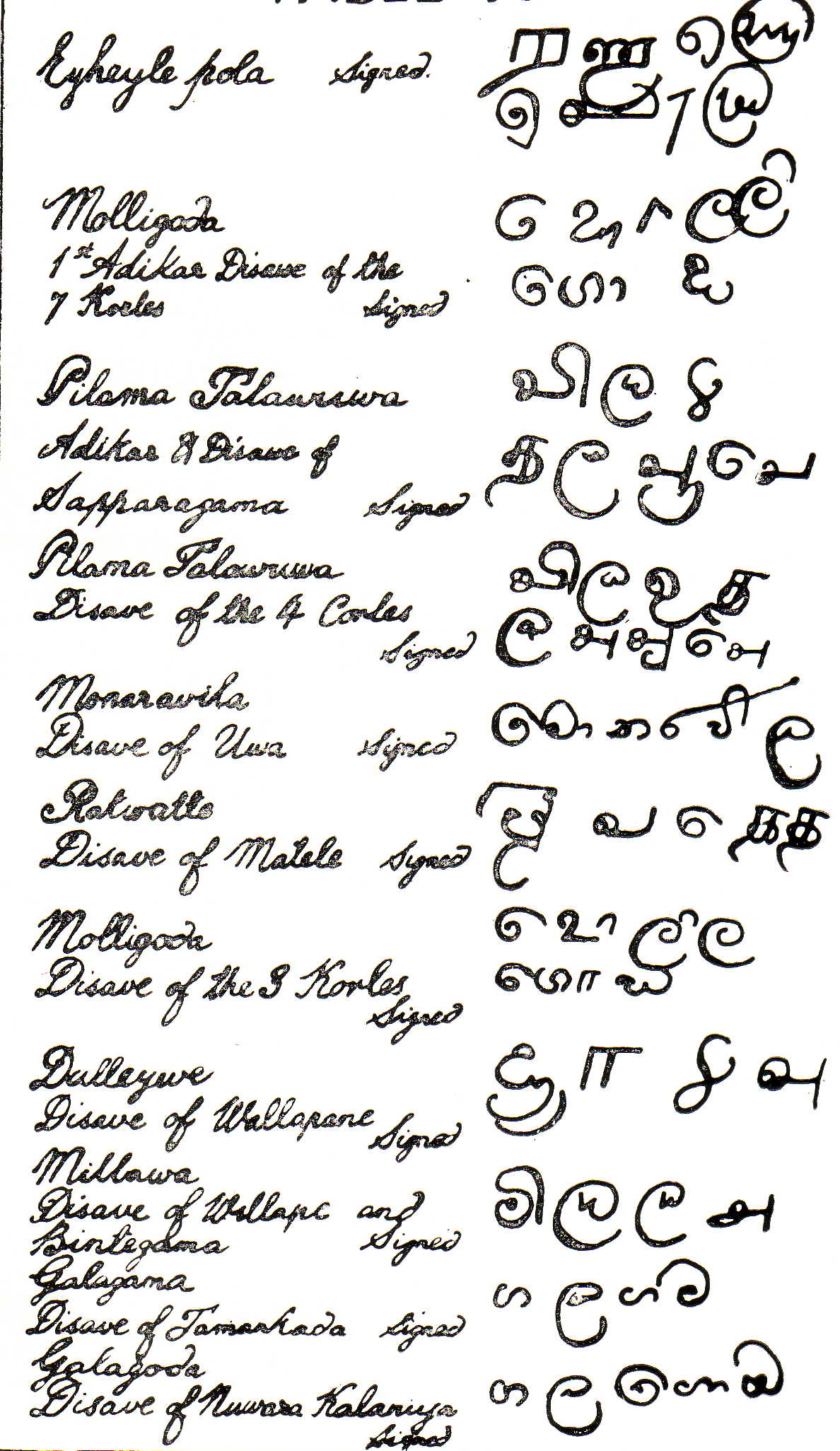

Table 10 shows that all except one of the eleven Sinhala Chiefs who signed the document wrote their signatures not entirely in the modern Sinhala script but in a mixed script of Sinhala, Tamil and Malayalam characters. The handwriting is clearly their own as it shows that although they were literate they did not possess a high degree of literacy and mistakes in orthography and malformations of even the Sinhala letters which are apparent in the signatures would not have been made by their secretaries or scribes if the signatures were appended by them for their Chiefs. There is no evidence that any of the 11 Chiefs were of recent Tamil or Malayalee descent. But if they were, the order of expulsion on all male persons of the ‘Malabar’ race would have applied to them. The Sinhala version refers simply to such persons as ‘Demalas’ orTamils…

The explanation for the use of Tamil and Malayalam characters in the signatures may be found in the fact that the last dynasty of Sinhala kings was of Tamil origin from Madura and the Tamil script would have been frequently used in the court. The characters of the Sinhala script were fully developed at that time as shown by the script used for the Sinhala version of the proclamation written by the side of the English version. It can therefore confidently be assumed that as late as 1815 the Malayalam and Tamil scripts were so well known in Sri Lanka that the non-scholarly population were accustomed to use these characters in their writings in Sinhala rather than the artistic Sinhala characters equivalent to the Tamil and Malayalam characters which were used only by professional scribes and monks.

Ralph Pieris points out in a footnote that in the case of the Kandyan Sinhalese there was the very slight admixture of Tamil blood particularly in court circles and that the original Kappitipolas were full blooded Tamils who came to the island with some Malabar king, presumably subsequent to 1739 when the Malabar dynasty was instituted. Yet it was these persons of the Malabar race i.e, Tamils who had come as courtiers from Madura who were banished in the Proclamation of 1815…”

My Specific Comments

In my reading, the earliest account by Sir Emerson Tennent (1859) was pro-British, because he was a high ranking British official and the blame for Kandyan kingdom annexation was placed solely on the atrocities of monstrous Kandyan Nayakkar King. In the description of Tennent, the role of British governor and his associates were exemplary and they were hardly interested in annexing the Kandyan kingdom for their own nefarious motives! Even the top Sinhalese traitor Eheylapola was “satisfied by being recognized as ‘the Friend of the British Government’”.

20th Century accounts of P. Arunachalam, Sir Charles Jeffries, Mendis and Pakeman, and that of Paul Jayarajan were less partial. Literally, there were four parties involved. Kandyan king, Kandyan aristocracy, Kandyan people (commoners) and British rulers. 20th Century accounts offered by Pon. Arunachalam and others present the case as a conflict between the Nayakar King and the Kandyan Sinhalese aristocracy. The king was tolerated by the Kandyan people. But the Kandyan aristocrats sided with the British rulers and betrayed the kingdom and the people.

Among the cited sources, only Paul Jayarajan has provided a facsimile copy of the 11 signatures of the Sinhalese chiefs, who had signed the 1815 Kandyan Convention. I provide a scan of it nearby. Their decipherable names (in English alphabets) are as follows:

Eyheylepola

Molligoda

Pilama Talawuwa

Pilama Talawuwa

Monaravila

Ratwatte

Molligoda

Dulleywe

Millawa

Galugama

Galagoda

They were the higher echelon of Kandyan aristocracy in the early 19th century. Among these names, many do know that former prime-minister madam Sirimavo Bandaranaike belonged to the Ratwatte clan. March 19th issue of the Colombo Daily News carried a memorial opinion piece by S.B. Karaliyadda with a caption ‘Bicentennial reminiscence of betrayal’. But the electronic edition of the version which I checked hardly mentioned a word about, what this ‘betrayal’ was!

Cited Sources

- Arunachalam: Sketches of Ceylon History, 2nd ed., Asian Educational Services, New Delhi, 2004 (first published in Colombo, 1906).

Paul M. Jayarajan: History of the Evolution of the Sinhala Alphabet, Printed at The Colombo Apothecaries Co, Colombo, not dated (probably 1976?, according to an annotation in H.A.I. Goonetilleke’s A Bibliography of Ceylon, vol.5, 1983.)

Sir Charles Jeffries: Ceylon – The Path to Independence, Pall Mall Press, London, 1962.

S.B.Karaliyadda. Kandyan Convention – Bicentennial reminiscence of betrayal. Colombo Daily News, March 19, 2015.

G.C. Mendis and S.A. Pakeman: Our Heritage. III. Ceylon and World History from 1796 to the Beginning of the Second Great War, The Colombo Apothecaries’ Co, Colombo, 1962.

Sir James Emerson Tennent: Ceylon – An Account of the Island Physical, Historical and Topographical with Notices of its Natural History, Antiquities and Productions, vol. 2, Asian Educational Services, New Delhi, 1999 (first published in London, Longman, Green, Longman and Roberts, 1859)

It is time that the island Tamils looked to the future with foresight. The old fashioned ideas are archaic only useful as dusty shelf props. In this new digital 21st century Tamils ought to forge their way not bound by class, caste, creed, or anything that would fetter them to the shackles of the past. Hindsight of history is a good thing with 20/20 vision. When we let history repeat itself it always come out as a farce.

Let new thinking flourish!

Naivete of Surya’s comments is nothing but appalling. What’s this so-called new thinking,? Colonialism and imperialism still rules the roost from the days of Alexander, Julius Cesar to Obama, Putin and Modi. Only the names change -but the principles of ruling the underclass, based on color, creed, and used language remains the same.

It is a history lession to present day occupyers of Jaffna kingdom how much of land of Tamils they have appropriated for Sinhalese and Muslims while descendents of real Tamils left to fend for themselves in the jungle after so called wat for their liberation from the last Tamil rule as recently as 5 years with their own army navy and air force only defeated with the help of India Chinese Pakistan and west

No wonder foolish and lazy Indians allowed 1987 accord to unite north and east of tamileelam to separate to build ports and fish in indian ocean while indian Tamil subjected to arrest while doing the same and Chinese now dictate terms to sl and India .

Malabar was the link language when that document was signed. That is why Moslem merchants speak Malabar as it was the language of commerce as well. English became the link language after they arrived.

Tamils are slaves brought to Ceylon. There were no Tamils in Ceylon before British.

http://jaffnahistory.com/Northern_Province/Sinhala_Villages_of_Jaffna_1695.html

To Surya:

History, despite its wrenching pain, cannot be unlived, but if faced with courage, need not be lived again.

-Maya Angelou

Hi Vibushana

“Tamils are slaves brought to Ceylon. There were no Tamils in Ceylon before British”- as usual you have pulled this out of your rear end.

your comments devoid of any intellectual prowess makes any fora descend to an abysmal low level and cosequentially will lose its seriousness.