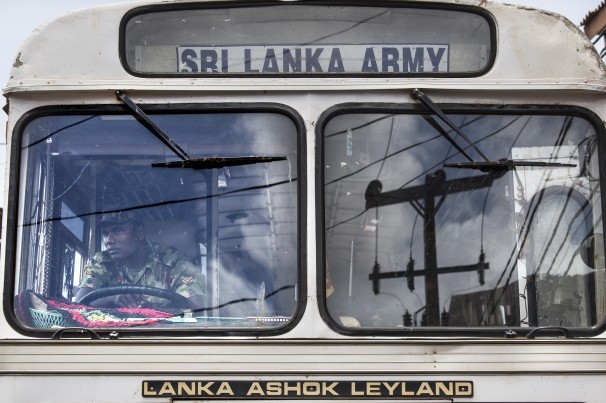

June 8, 2015 A Sri Lankan soldier waits at a traffic light in downtown Jaffna, where the military’s presence remains a common sight. Paula Bronstein/For The Washington Post

PALAI VEEMANKAMAN, Sri Lanka — When Parameswari Uthayakumaran saw her house last month for the first time in 25 years, she stood in the rubble and wept.

All her belongings, the doors, even the tiled roof had been stripped away. She had last seen the house in November 1990, when her family fled from Sri Lankan gunships bearing down on her neighborhood, firing from the sky and littering the grass with leaflets telling Tamil families to leave the area. She had time to grab only a bit of sugar and tea.

The Sri Lankan army declared the area a high-security zone, and the government only allowed families to return in April, six years after the end of the civil war that claimed more than 80,000 lives.

“The moment I saw this I couldn’t control myself,” Uthayakumaran said on a recent hot day, weeping anew. “The whole area had grown up, just like a forest.”

Since taking office in January, Sri Lanka’s new president, Maithripala Sirisena, has said that reconciliation in the country’s north and east — rent by nearly three decades of conflict between military forces and a violent insurgency of ethnic minority Tamils — is among his administration’s top priorities.

- Parameswawri Uthayakumaran sits inside the remains of the house she grew up in as many come back to an area that used to be a high security zone. (Paula Bronstein/For The Washington Post)

Speaking at an event honoring soldiers last month, Sirisena said that although the damaged buildings and destroyed roads have been rebuilt, there has been no reconciliation process to “rebuild broken hearts and minds.”

Sirisena’s government has begun returning land to families whose property is still being used by the military, as well as resettling those remaining in displacement camps or living with relatives — officially about 13,000 families, although civil society activists say the number is higher.

He has pledged a domestic inquiry into the wartime behavior of the Sri Lankan military and their opponents, the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam — the U.S.-designated foreign terrorist organization that fought for years for a separate homeland. Sirisena’s government successfully argued, with the support of the United States, to delay until September the release of a U.N. High Commissioner for Human Rights report on possible wartime atrocities so it could better cooperate with investigators. And it is setting up an office in the north to help thousands of war widows like Uthayakumaran.

But Tamil leaders are not convinced that these efforts will be enough to unify the Tamil and Hindu north and east with the majority Sinhalese Buddhist south. They say that they are concerned that Sirisena’s moves are symbolic and don’t address issues such as the Tamils’ desire for greater autonomy and the withdrawal of troops.

“It’s too early,” said Kumaravadivel Guruparan, a law lecturer at the University of Jaffna and a spokesman for the Tamil Civil Society Forum. “Unless you address these issues head-on, you’re not going to see any true progress.”

New bricks have patched up the walls of the historic fort in Jaffna, the largest city in the island nation’s north, where the civil conflict was centered. But the darker outlines of the original bombed-out structure remain. In the six years since the Sri Lankan army defeated the rebels on a beach in Mullaitivu 70 miles away, a measure of stability has returned.

The “war tourists” who used to arrive by busloads have been shooed out of the railway station, where they once spent the night. The station has a fresh coat of paint and receives the region’s new north-south train, the Queen of Jaffna, which made its inaugural run in the fall on tracks that had been closed since 1990.

The country’s previous president, Mahinda Rajapaksa, poured millions into reconstruction and allowed provincial council elections for the first time in years in 2013. But critics say Rajapaksa — an autocrat in power for nearly a decade — did little else to salve the deep wounds.

In 2011, a U.N. panel found likely human rights abuses by both sides in the conflict, particularly in the waning days of the war when an estimated 40,000 civilians died. The Sri Lankan army repeatedly shelled no-fire zones, hospitals and supply lines, while the LTTE used civilians, including children, as human shields and forced them into military ranks, according to the report.

The Sirisena government pledged to set up a “domestic mechanism” to investigate these alleged abuses and said it will accept “technical assistance” from the United Nations.

But the Tamil minority is skeptical because earlier panels have borne scant fruit and the victims have not been consulted on the process, Guruparan said.

Meanwhile, an investigation into the thousands who disappeared during the fighting is continuing. And the government is trying to find ways of helping the large number of war widows — among 31,000 female heads of household in the Jaffna district alone, according to Navaratnam Udhayani, Jaffna’s district coordinator for women. Many of them can’t find suitable jobs to support their families and must deal with cultural norms that frown upon remarriage.

Sivapalu Levathiammah, 57, a war widow, lives in a three-room house with a corrugated tin roof in a small village on the outskirts of Jaffna.

She has struggled to support her children, pickling seafood since her husband died in the conflict. She is continuing to search for her son Sivanasan, a fisherman she believes was taken by the army in 2009.

“I have dreamed my son came to see me, hugged me and asked for rice and curry,” she said. “I have this dream at least two times in a month.”

The government’s process of returning land has been complicated, with only about 1,000 acres returned so far.

That’s a small fraction of the nearly 10,000 acres of private land the government estimates is still in the hands of the military, according to Ranjini Nadarajapillai, the secretary for the country’s Ministry of Resettlement. Activists think this number is higher.

The process has been complicated by the fact that the Rajapaksa-era military went on its own building spree after the war’s end, erecting new camps, beachfront hotels and even golf courses for its own use.

Since the government permitted Uthayakumaran and her neighbors to return to their homes in April, the neighborhood has taken on a new life. Residents come from far away every day to clear the land of brush. The sound of chain saws rings through the air.

The government is supposed to have given these returnees about $280, but so far they say they have received only $100 to clear their own land. Here and there, warning posters containing photos of land mines are placed on fences, including telephone numbers to call if the objects are found.

Uthayakumaran said she is hopeful that her neighbors will also return to the once-prosperous community of cement factory workers, teachers and other middle-class residents.

“I’m so much happier now that I’ve come to my own house,” she said.

Every day, a local Hindu priest comes to do the traditional “puja” blessing at the neighborhood’s small temple, crowning the elephant head god Ganesh statue with flowers, burning incense and chanting ancient mantras.

When K. Ganeshamoorthy Sarma, 70, first arrived April 21, the lot was so overgrown it could be reached only by a cattle trail to a nearby pond. He was relieved to see the 350-year-old banyan tree and the worn granite Ganesh still tucked in its massive roots.

Now, the returning neighbors come by for his blessing, the first step toward rebuilding their community. The government has promised to provide them water and electricity, he says, “so they feel there is hope.”

Read more

Kerry: U.S. will deepen ties with Sri Lanka

Children of Sri Lankan refugees born in India uncertain about future

Amantha Perera contributed to this report.