Archaeological Sites Islandwide Plundered for Priceless Artefacts

Well organised network of gangs equipped with sophisticated machinery openly ‘excavate’ ancient temple lands.

The voice at the end of Inspector Rohana Chaminda’s line was agitated. There were “men in ties” scoping out his temple, it said. Could the police please come and see what this was about? It was the Chief Incumbent of the Kanabisawaramaya Temple in Wellawaya, calling on Wednesday. He was suspicious, because this was the third time in recent weeks that such a group was visiting. Their pretexts seemed hollow and they were overly interested in the location of monuments and ruins.

Kaludiyapokuna a historical archaelogical site in Dambulla that was plundered last year. Pic by Kanchana Kumara Ariyadasa

“Get their identities, apey hamuduruwaney,” advised Inspector Chaminda, Officer-in-Charge (OIC)- Archaeology Dept’s Antiquities Protection Division in Colombo, promising to come within a week.

This was no laughing matter. Kanabisawaramaya is an ancient temple with an unexcavated dagoba and many ruins. Experience had taught both the Inspector and the Chief Incumbent to be wary of people “collecting intelligence” at such places.

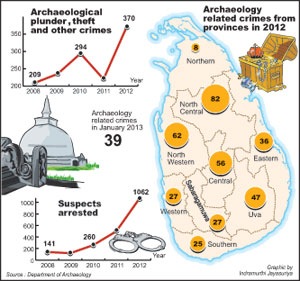

In 2012, there was a 70% rise in plunder of archaeological sites over the previous year. Statistics from the Archaeological Dept show that the number of incidents jumped from 220 to 370—more than the number of days in a year.

Statistics for 2013 are equally alarming. There were 39 incidents reported in the first 37 days of the year alone. Officials warn that, not only is “treasure hunting” rapidly increasing, it has become more organised, blatant, widespread and sophisticated. Laser guns are among the latest equipment employed in illegal excavations —an indication of just how well these operations are now financed.

The North-Central and Wayamba Provinces are the worst affected. Since the war ended, archaeological and historical sites in the North and East are subjected to relentless pillaging.

Inspector Chaminda said members of the army, navy and air force (both deserters or, less frequently, in-service personnel) and policemen are sometimes found to be involved, as are some Buddhist monks. While he didn’t incriminate mainstream politicians, he admitted that some local government and provincial level representatives were “not free of blame”.

The inventory, as kept by the Dept, includes theft of artefacts, destruction of sites and monuments, illegal excavation of archaeological sites (the most numerous in the list) and other violations of the Antiquities Ordinance.

“Earlier, you were more likely to stumble upon a harmless villager chipping away at the earth with his farm tools,” explained Udeni Wickramasinghe, head of the Department’s Special Unit for Prevention of Destruction and Theft of Antiquities. “Today, backhoes are used, and the wrongdoers are not afraid of being seen.”

The machinery is usually brought to the location on the pretence that a well or cesspit is to be dug. In November, seven suspects were arrested while using a backhoe to explore the site of an ancient dagoba in Mottayagala, Thirukkovil. Their excuse had been that they were building a road—right through the unexcavated body of the stupa!

“The worst damage is done to mounds containing ruins, to image houses (pilima gewal), to dagobas, moonstones (sandakadapahan), balustrades (korawak gal), guard-stones (mura gal), ancient village boundaries marked out with stone and to rock faces with ancient inscriptions,” said Mrs. Wickramasinghe. “People excavate ruins whenever they believe there is treasure buried inside or underneath. They also dig up caves, to a lesser degree.”

Ancient statues are found discarded, missing a nose or an ear; thieves discover that they aren’t made of gold and throw them with callous disregard to their priceless historical value. “I once inspected a statue stolen from the Burunnawa Raja Maha Viharaya in Warakapola, that thieves had drilled into,” said Mrs. Wickramasinghe. “Since there was predictably no gold, they had used wax to fill up the holes.”

Cupboards in the Antiquities Protection Division of the Archaeological Department in Colombo are brimming with files. “I can give you plenty of cases,” said Inspector Chaminda, settling tiredly into his swivel chair.

Perched on a window ledge by his desk are four unsightly pieces of rock, all of archaeological value. One of them has been carved off a bigger boulder. There isn’t even a ripple on the incised side. Inspector Chaminda explained that he had picked it up inside a cave in Maduru Oya National Park.

“This is so smooth, because it was cut using a laser gun,” he said. In 2009, following a tip-off, Inspector Chaminda and his team, accompanied by indigenous people from Dambana, had trekked 18 km to reach a cave. “We left at 7pm and reached the site at 7am,” he said. “It was too late. We didn’t catch the wrongdoers. But we did find the laser gun and a generator. Inside the cave there was a pit 55-feet deep. We were informed that 50 people had been digging for three months, for payment of Rs 1,000 a day.”

Police are investigating the activities of several gangs. Many more are yet to be identified, let alone investigated. One network of hunters, recently busted, was implicated in three illegal excavations in Wellawaya, Haputale and Buttala.

A telephone number scribbled on a wall calendar in the home of a member, led to the discovery that the gang had agents islandwide. One of its main organisers was a security forces deserter from Ruwanwella, who was pretending to be the bodyguard of an influential minister’s wife. Another was a timekeeper from Wellawaya, who was residing in Buttala, as an employee of the Uva Provincial Council. He masqueraded as an officer of the Archaeological Dept.

The husband of an Avissawella-based lawyer was involved in all three incidents. The chief financier was found to be the husband of a bank manager in Colombo. Before each excavation, a “kattadiya” (exorcist) performed ceremonies. They were residents of Thanamalvila, Buttala and Bulathkohupitiya.

Continuing inquiries are proving that the ring is much wider than previously thought. And this is only the tip of the iceberg.

Artefacts stolen from war-ravaged N-E sold as antiques in Colombo

Existing legislation inadequate to arrest the trend

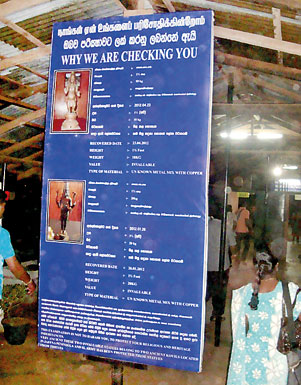

At the Omanthai checkpoint, on the Jaffna-Kandy road, is a billboard depicting images of two statues of Hindu deities. It states in Sinhala, Tamil and English, that security forces are constrained to peruse the luggage of commuters, because miscreants had attempted to smuggle the two images to the South.

The billboard at the Omanthai checkpoint. Pic by Priyantha Hewage

The reference is to two incidents. In January 2012, the 12th century statue of a Hindu deity was found concealed in a Jaffna-Diyatalawa bus. Three months later, the Army at Omanthai, found another statue, this time of God Kubera, in the luggage of a commuter on a Jaffna-Colombo bus.

It is feared that many other priceless artefacts simply go undetected, to be sold to unscrupulous merchants and collectors of antiques. In November 2010, Padmanadan Sharma, a Hindu prelate, giving evidence before the Lessons Learnt and Reconciliation Commission (LLRC), lamented that many Hindu temples in the North were damaged in the war, and remained inaccessible to people.

“We are sorry to say, today, monuments traditionally worshipped, which should be preserved as historical monuments, are taken to Colombo, and sold as antiques,” he said.

“During the war, when people could not go there, the artistic objects of the temple, such as chariots, statues and bells and the like have been removed from there and sold as antiques in Colombo,” Mr. Sharma continued.

Alluding to one antiques shop, he said, “Artefacts of a bygone era, such as boxes used for storing paddy, traditional grinding instruments, ancient towers, pillars of houses and doors in the Wanni areas, had been brought there for sale. Please take steps to prevent their sale.”

The Sunday Times found existing legislation inadequate to deal with this issue. It is not illegal to transport, sell or keep antiques, provided there was proof of the items being legitimately acquired. However, the authorities do not habitually try to establish the origins of antiques sold in shops around the country.

The shops are not required to register with the Archaeological Dept. It is also not possible for untrained persons to determine whether various artefacts vended in these outlets, were authentic (and, if so, what their origins were) or replicas.