by Kamala Thiagarajan, BBC, London, February 12, 2024

Coastal towns across southern India still reveal how medieval travellers once used the power of language to further trade and forge deep connections.

One warm summer evening in 2008, when Mohamed Sultan Baqavi was a 26-year-old student at Arabic College in the South Indian town of Vellore, he made a remarkable discovery. After offering prayers in the city’s Labaabeen Qabrusthan mosque, where generations of his spiritual gurus were laid to rest, he caught sight of a man sweeping the courtyard.

Boat in the sea at Mahabalipuram beach, Tamil Nadu, India (Credit: Sandipan Dutta/Alamy)

The man gathered the debris – scraps of paper, rubble and leaves – and piled them up beside a dried-up well near the mosque’s entrance to set alight. As Baqavi was preparing to leave, a gentle breeze blew his way, carrying with it a page from the rubbish heap. When he pried it from his face, Baqavi was startled to find that the scrap of paper was a part of a book. He knew that some mosques used their dried-out wells as storage for rare manuscripts, and stray pages from these often littered courtyards. Could this be one of them, he wondered?

Baqavi took a closer look at the now-burning heap of rubbish and hurriedly fished out an entire book from the bonfire. After dousing the flames, he opened it to find pages of rare script that he immediately recognised. It was written in the long-lost language of Arwi.

Baqavi, now a professor at Jamia Anwariyya Arabic College in the South Indian state of Kerala, had been reading Arwi literature since he was four years old. But very few people, even among Muslims who read Arabic, could recognise this script.

Arwi dates to the 8th Century CE when travel and trade in the medieval world sparked a curious intermingling of tongues. It leapt to prominence in the 17th Century, when more Muslim Arab traders landed in the South Indian state of Tamil Nadu, which was full of Tamil speaking people. The traders brought with them rich tapestries and the finest textiles and perfumes like frankincense and myrrh – records say they longed to establish a deeper connection with the local people because they felt connected by a common religion but spoke two different languages.

The Arabic that the traders spoke intermingled with the local language of Tamil to create what scholars call Arabu Tamil, or Arwi. The script employs a modified alphabet of Arabic, but the actual words and their meanings are borrowed from the local Tamil dialect.

“Arabic Tamil, called Arwi, was just one of the many languages that found expression in Arabic script,” explained Mahmood Kooria, a lecturer in the history of the Indian Ocean world before 1750, at the University of Edinburgh. “The Indian Ocean trade at the time was dominated by Arabian and Persian traders who landed in India before European colonialists,” he said. “Travel and trade shaped how these languages evolved.”

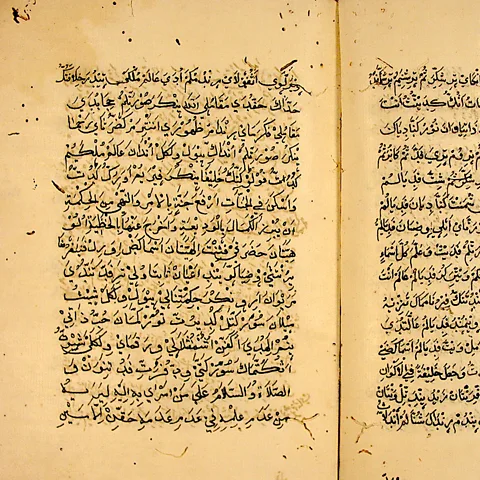

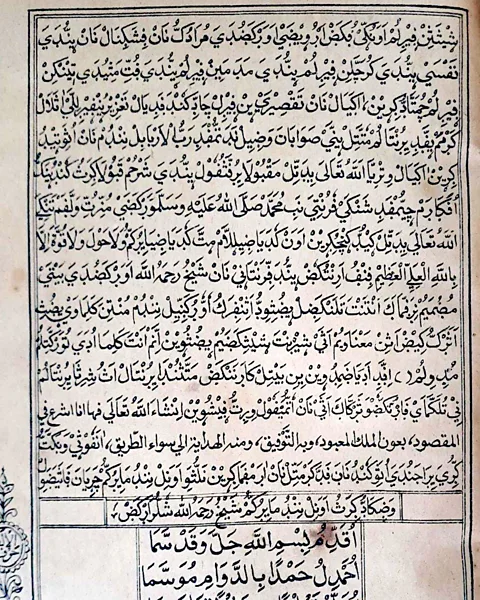

Arwi script employs a modified alphabet of Arabic, but the words and their meanings are borrowed from the local Tamil dialect (Credit: Ahamed Zubair)

Arwi extended to nearby Sri Lanka, which had its own Tamil-speaking population too. And though the language was thought to be on the brink of extinction after the 18th Century, when European colonial powers began to dominate the Indian Ocean trade and native speakers began to dwindle, today it’s facing a curious revival. University graduates are studying it, and in a handful of villages along the coast, many Muslim women pride themselves in singing prayer songs in the ancient tongue.

“Many people don’t realise its value. Families in my hometown of Kayalpatnam [in the South Indian state of Tamil Nadu] consider it a sacred link to their roots,” Baqavi said.

To understand how Arwi originated and how it evolved, one must travel to South India’s coastal towns that are predominantly Muslim settlements.

Kilakarai, 530km south of Tamil Nadu’s capital city of Chennai, is one such town. Located on the banks of the Bay of Bengal with a population of 38,000, it is home to the Jumma Pali Masjid – one of the oldest mosques in India, built in 628 CE. The mosque was believed to have been built by Yemeni merchants and traders who had arrived by sea to these parts. Two large tombstones of revered saints are tucked away beside the mosque’s ornate pillars and mint green minarets. The inscriptions are in Arabic on one end and in the local language of Tamil on the other.

“Tamil has 247 letters. Arwi had a much more manageable alphabet – just 40 letters – perfect for medieval seafarers who wanted to quickly pick up proficiency in the tongue… enough to trade and earn their livelihood in a new land,” said K MA Ahamed Zubair, associate professor of Arabic at The New College in Chennai, who teaches the Arwi script to his students.

Unlike the North, where Muslims are often discriminated against, in South India, they integrated seamlessly and have lived in harmony for centuries

He added: “Unlike the North, where Muslims are often discriminated against, in South India, they integrated seamlessly and have lived in harmony for centuries. The Arabs were particularly welcomed since they brought prosperity through trade. As per some records, Arwi was used as a secret language, a means of communicating privately [with locals] when faced with competition from the British East India Company.”

Mahmood Kooria helped catalogue the Arabic Tamil and Arabic Malayalam literature in the British library over four years (Credit: Mahmood Kooria)

Other regional Indian languages such as Gujarati, Bengali, Punjabi and Sindhi were written out in Arabic script as well, Zubair said. Each language was unique – born out of a fusion of Arabic and the local tongue. But Arwi continued to flourish even when Arab traders moved on from the Tamil Nadu region because of a significant Tamil-speaking population overseas, said Zubair. “As per historical records, Arwi travelled [with Arabic traders] to Sri Lanka, Sumatra, Malaysia, Singapore, East and South Africa as well.”

Arabic Tamil and Arabic Malayalam were so popular because they had a rich literary and oral tradition, added Kooria. Across India and Sri Lanka, 2,000 books written in Arabic Tamil have been identified. In Kerala, researchers are trying to preserve rare Arabic Malayalam manuscripts.

However, in order to preserve the manuscripts, you first have to find them. And that has proved to be quite the challenge. Baqavi, who found the book being burnt on the premises of the mosque, says he’s now collected more than 300 Arwi and Arabic Malayalam books from different parts of India and Asia. “I found these books in dried out old wells, in graveyards (called Qabarusthans) and old unused lofts in Muslim homes,” he said. (Many of these texts from private collections are now being digitised and uploaded online at the Mapilla Heritage Library.

As a result of colonialism, manuscripts also found their way to the British library in London, where they are housed today. Kooria, who reads and writes Arabic Malayalam, has been assisting the British Library in cataloguing these texts for the last four years. “I was stunned to find so many on history, religion, medicine and culture; [and] many of these were written by women,” he said.

It’s proof of how Muslim women had a strong voice and identity and were part of a matrilineal tradition

A significant number of these books by women authors were written for other women, addressing issues such as childbirth and sexuality, and reflecting on domestic issues or discussing cuisines and culture, said Ophira Gamliel, a lecturer in South Asian Religions at the University of Glasgow. “It’s proof of how Muslim women had a strong voice and identity and were part of a matrilineal tradition,” said Gamliel.

Baqavi has been collecting Arwi books and manuscripts from across India and Asia, including this book of Arwi poetry from 1314 (Credit: Muhammed Sulthan Baqavi)

And while these fusion dialects are not spoken on a daily basis anymore, Arwi and Arabic Malayalam still live on today because of these books and songs.

See Arwi for yourself

The script can be seen at Pulicat Lake, around roughly 55km from Tamil Nadu’s capital city of Chennai. The lake is known for its teeming population of migratory birds, including flamingos, storks and kingfishers.

This used to be the site of a major port city, and in the 1620s, the Portuguese colonised the lagoon, followed by the Dutch. However, even before the European colonisers, as far back as 1336, Muslim traders from Persia and Arabia made Pulicat Lake their home. Today, travellers can see old tombstones at Pulicat with messages written in Arwi, although many of the monuments and stone slabs that feature the script are yet to be properly documented.

Arwi can be also found on the tombstones at the Jumma Pali Masjid in Kilakarai.

Getting together to sing these songs is a big social event. “It’s like a women’s club,” laughed 18-year-old Khizr Magfira, who is studying a bachelor’s degree in commerce at a local college in Kayalpatnam. “Every household has at least one member who knows Arwi well and speaks fluently,” she added.

“In the narrow lanes between our homes, groups of women gather during special occasions such as the birth month of Prophet Mohammed (during the third month in the Islamic calendar, roughly in September) to sing these songs together,” said Magfira. “When I see tears in their eyes as they sing these songs, I know how deeply they understand and cherish it. It’s very therapeutic.”

She’s learning Arwi herself, inspired by the elders in her household. It helps that she’s learnt Arabic since the age of four and is fluent in Tamil. Some youngsters from the town have even got together to create an Arwi keyboard that’s compatible with an Android phone.

Magfira’s relative, Khizhr Fathima, says they encourage youngsters to learn the Arwi script the old way – by rewarding anyone, child or adult, who painstakingly copies out the script by hand. “It’s an age-old tradition in this town,” she said. She recently gifted her neighbour Rs 500 (£4.75) because she had the most beautiful handwriting she’d seen.