An updated version

by Sachi Sri Kantha, July 12, 2023

Front Note by Sachi

The original version of this commentary of mine (written under the pseudonym C.P. Goliard) first appeared in the Tamil Nation print edition (London) of August 15, 1991. For digital preservation, it was posted in the sangam site in April 2002. https://www.sangam.org/ANALYSIS/Sachi04_01_02.htm

Sir Muthu Coomaraswamy

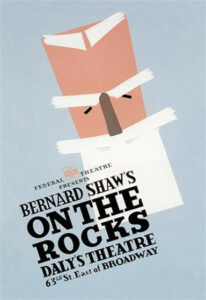

Now, to mark the 90th anniversary of Bernard Shaw’s political play ‘On the Rocks’ that premiered in Nov 25, 1933, [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/On_the_Rocks:_A_Political_Comedy]

Shaw’s biographer Michael Holroyd’s vol. 3 (Bernard Shaw 1918-1950- The Lure of Fantasy) was published only in 1991, the same year my original commentary was written. Now, I revisit my original commentary, with additional inputs on the model of the character Sir Jafna Pandranath, created by Shaw in two parts: (1) Original version of 1991, and (2) Additional notes. Now that, due to historical manipulations of the British colonial period, Mr. Rishi Sunak (a guy of Indian descent with Hindu origin) became the prime minister of UK in 2022, had he lived, Shaw might have chuckled to hear this news!

Original version of 1991 (unaltered)

What is common with the names Dr. Blenkinsop, Sir Bemrose Hotspot, Sir Dexter Rightside, Eliza Doolittle, Epiphania Fitzfazzen, Prof. Henry Higgins, Mrs. Kitty Warren and Sir Jafna Pandranath? All these are fictional characters created by that inimitable wit, iconoclast and distinguished dramatist George Bernard Shaw (1856-1950).

While Eliza Doolittle and Prof. Henry Higgins have become popular worldwide due to the 1964 movie My Fair Lady, not many know that Shaw also immortalized the name of Jaffna by using it to one of his characters in the political comedy, On the Rocks, written in 1933.

It has been appraised that Shaw framed the character of Sir Jafna Pandranath after the 19th century Tamil intellectual Sir Muthu Coomaraswamy (1834-1879), who was the father of reputed orientalist Dr.Ananda K. Coomaraswamy (1877-1947). Sir Muthu Coomaraswamy moved among the elite circles of Victorian England and counted Benjamin Disraeli (1804-1881) as one of his friends.

Sir Muthu Coomaraswamy sketched by an artist

When Shaw arrived in London from Dublin in 1876, Disraeli was the Prime Minister of Britain. In that year, Disraeli also conferred on Queen Victoria, the new title of ‘Empress of India’. In the play On the Rocks, the character of Prime Minister Sir Arthur Chavender seems modeled after Prime Minister Disraeli. The plot of On the Rocks is set in two acts at the Cabinet room in No.10, Downing Street. The Act 1 takes place in mid-July. The Prime Minister Sir Arthur Chavender is worried about the increasing rowdyism of street demonstrations by the unemployed and wants the Chief Commissioner of Police to use stern methods. The Police Commissioner suggests that the best way to keep the unemployed occupied is with terrific speeches. Then one member of a delegation from the Isle of Cats which visited the Cabinet room advices the prime minister to read Karl Marx. This he does and later delivers a fiery socialistic speech.

Act 2 of the play takes place in November at the Cabinet room again. Five Britons engaged in discussion were, Sir Arthur Chavender, Sir Dexter Rightside (Foreign Secretary), Sir Broadfoot Basham (Chief Commissioner of Police), Sir Bemrose Hotspot (First Lord of the Admiralty) and Mr.Glenmorison (President of the Board of Trade). Sir Jafna Pandranath comes to congratulate the prime minister on his new program of reform, about the nationalization of land.

I will allow Shaw to introduce his Tamil character Sir Jafna.

“Sir Jafna: Hello! Am I breaking into a Cabinet meeting?

Sir Arthur: No. Not a bit. Only a few friendly callers. Pray sit down.

Sir Dexter: You are welcome, Sir Jafna; most welcome. You represent money; and money brings fools to their senses.

Sir Jafna: Money! Not at all. I am a poor man. I never know from one moment to another whether I am worth thirteen millions or only three.

Sir Bemrose: I happen to know, Sir Jafna, that your enterprises stand at twenty millions today at the very least.

Glenmorison: Fifty.

Sir Jafna: How do you know? How do you know? The way I am plundered at every turn! (To Sir Dexter) Your people take the shirt off my back.

Sir Dexter: My people! What on earth do you mean?

Sir Jafna: Your Land monopolists. Your blackmailers. Your robber barons… You were quite right at the Guildhall last night, Arthur. You must nationalize the land and put a stop to this shameless exploitation of the financiers and entrepreneurs by a useless, idle, predatory landed class…”

Sir Dexter Rightside becomes enraged by the Prime Minister Sir Arthur Chavender’s radical reform proposal and the support given by Sir Pandranath. He loses his temper and calls Sir Jafna, “a silly nigger pretending to be an English gentleman”. This derisive comment makes Sir Jafna to explode with indignation and Shaw put in Sir Jafna’s mouth, what Tamils pride about themselves.

Let me quote Shaw, in the words of Sir Jafna:

“I am despised. I am called nigger by this dirty faced barbarian whose forefathers were naked savages worshipping acorns and mistletoe in the woods whiles my people were spreading the highest enlightenment yet reached by the human race from the temples of Brahma the thousands fold who is all the gods in one. This primitive savage dares to accuse me of imitating him; me, with the blood in my veins of conquerors who have swept through continents vaster than a million dog-holes like this island of yours. They founded a civilization compared to which your little kingdom is no better than a concentration camp.

What you have of religion came from the East; yet no Hindu, no Parsee, No Jain, would stoop to its crudities. Is there a mirror here? Look at your faces and look at the faces of my people in Ceylon, the cradle of the human race. There you see Man as he came from the hand of God, who has left on every feature the unmistakeable stamp of the great original creative artist. There you see Woman with eyes in her head that mirror the universe instead of little peep-holes filled with faded pebbles… you call me nigger, sneering at my colour because you have none… I should dishonour my country and my race by remaining here where both have been insulted… But I now cast you off. I return to India to detach it wholly from England and leave you to perish in your ignorance, your vain conceit, and your abominable manners.”

Elizabeth Clay Coomaraswamy (nee Beebe) in 1925

After the exit of Sir Jafna, the other British characters continue the conversation, in which Shaw brings forth the snobbery of colonial rulers.

“Sir Arthur: That one word nigger will cost us India. How could Dexy be such a fool as to let it slip?

Sir Bemrose: Arthur! I feel I cannot overlook a speech like that. Afterall we are white men.

Sir Arthur: You are not, Rosy, I assure you. You are walnut colour, with a touch of claret on the nose. Glenmorison is the colour of his native oatmeal, not a touch of white on him. The fairest man present is the Duke. He’s as yellow as a Malayan headhunter. The Chinese call us Pinks. They flatter us.

Sir Bemrose: I must tell you, Arthur that frivolity on a vital point like this is in very bad taste. And you know very well that the country cannot do without Dexy… I must go and see him at once.

Sir Arthur: Make my apologies to Sir Jafna if you overtake him. How are we to hold the empire together if we insult a man who represents nearly seventy percent of its population?

Sir Bemrose: I don’t agree with you, Arthur. It is for Pandy to apologize. Dexy really shares the premiership with you; and if a Conservative Prime Minister of England may not take down a heathen native when he forgets himself there is an end of British supremacy.

Sir Arthur: For Heaven’s sake don’t call him a native. You are a native.

Sir Bemrose: Of Kent, Arthur: of Kent. Not of Ceylon.”

Shaw ends the play with Sir Arthur Chavender deciding to give up politics, after discovering that Britain needs a revolution, but he is not the man to lead one. An excited unemployed mob breaks into Downing Street and windows of the Colonial Office are being stoned. Then, police mounted on horses arrive at the scene and disperse the crowd.

ADDITIONAL NOTES IN 2023

A comment on Shaw’s biographer Holroyd’s Notes

After 22 years of further research on Sir Jafna Pandranath character of Shaw, I provide these additional notes. Among Shaw’s oeuvre of 51 plays, in which he created over 600 characters, I consider his Sir Jafna character is somewhat unique in that he named an Asian city, as the first name of his character in ‘On the Rocks’. In a companion play of the same period, ‘The Apple Cart’, Shaw also named a character ‘Nicobar (Nick)’, derived from the Andaman-Nicobar islands that belong to India.

A notice for ‘On the Rocks’ play

Shaw’s biographer Sir Michael Holroyd (b. 1935) had provided minute details on the characterization and perceived reception for ‘On the Rocks’ play in London, USA and elsewhere. He had passingly mentioned about the Sir Jafna character in only one sentence as follows, without elaborating the model on whom Shaw had created this character:

“The case for fascism is put with the same lucidity as the case for socialism; the seductive strengths and parochial limitations of Western intellect confront the criticisms of Oriental culture (eloquently expressed by the Sinhalese plutocrat Sir Jaffna Pandranath).”

I detected two minor errors in the spelling of ‘Sinhalese’ and ‘Jaffna’, used by Holroyd in the above sentence. While Shaw (a stickler for details) had used the spelling ‘Jafna’ with one f in his script, Holroyd had used two ‘f’s, as the city Jaffna is spelt in English now. Also, Shaw had used ‘Cingalese’ in his script, while Holroyd had adapted the currently prevailing spelling Sinhalese. [Read below the description provided by Shaw’s lexicographer Phyllis Hartnoll and Ananda Coomaraswamy’s critique on the erroneous use of Cingalese word.]

The model for Sir Jafna Pandranath character – Sir Mutu Coomaraswamy

Though the general consensus was that Shaw based his Sir Jafna Pandranath character on Sir Mutu Coomaraswamy, few writers (journalists!) had promoted a view that it was based on politician S.W.R.D. Bandaranaike (1899-1959); Probably on the vague similarity based on the name – Bandaranaike and Pandranath, and also word ‘Cingalese’ used by Shaw. I had written in 2002, on the onomastics of Bandaranaike name in Sri Lankan history, incorporating the original research of James Rutnam and Yasmine Gooneratne [see, https://www.sangam.org/ANALYSIS/Sachi07_18_02.htm] In brief, the ancestors of Bandaranaikes from Tamil Nadu, originally received the name Nayaka Pandaram in the 15 century when they landed in the island, and with passage of time, it got twisted to Pandara Nayakam > Bandaranaike.

I provide three reasons to reject the view that S.W.R.D. Bandaranaike was the model for Sir Jafna Pandranath. First, internal evidence in the character’s lines written by Shaw (“What you have of religion came from the East; yet no Hindu, no Parsee, No Jain, would stoop to its crudities. Is there a mirror here? Look at your faces and look at the faces of my people in Ceylon, the cradle of the human race….) rejects this view. Shaw did NOT mention Buddhist! He mentions only Hindu, Parsee and Jain religions. Secondly, Bandaranaike was in Britain between October 1919 and Feb 1925. He was ONLY a young student at the Christ Church College, Oxford and didn’t have any political contacts to move in the elite circles of No. 10, Downing Street. Secondly, the social status of Sir Muthu Coomaraswamy, who was the first knighted Asian, during the reign of Queen Victoria in August 11, 1874, was very different. It is ridiculous to consider that Shaw (a meticulous playwright known for prudent characterization) would have framed an unmarried Asian student in his early 20s as a model to be moving along the aging Cabinet ministers and the prime minister of England. Thirdly, Sir Mutu Coomaraswamy’s first visit to UK was in May 1862, at the age of 28. He had practiced law in London before returning to Ceylon in 1865. He made his second visit to London in 1873, and married English lady Elizabeth Clay Beebe (daughter of William Beebe) of Kent in 1877, and returned with her to Colombo. Their only son Ananda was born in August 22, 1877.

While searching for details on Sir Muthu’s brief career in England, I came across a 2021 research note by emeritus professor Charles Smith of Western Kentucky University who had traced a copy of Sir Muthu’s book, in the library of famous naturalist Alfred Wallace (1823-1913), a contemporary of Charles Darwin. I provide three relevant paragraphs from Smith below.

“Recently I came upon several pieces of information that bear on this story. First, Wallace’s personal library, now owned in part by the University of Edinburgh, contains a volume by Sir Mutu (or Muthu) Coomaraswamy (1834-1879), Ananda’s father: his translation into English of Arichandra: The Martyr of Truth, a classic Tamil drama. The 1863 volume is not annotated, but bears the label of a local bookstore. Sir Mutu was an illustrious figure: a prominent lawyer, politician, and folklorist, and the first Tamil to be knighted. He spent some years in England in the early 1860s, and again, for a slightly briefer period, in 1873-75. During the second visit he married Elizabeth Clay Beebe, a young woman from a prominent family in Kent, before returning with her to Ceylon, where Ananda was born in 1877. A third visit to England was planned for 1879, but while Lady Coomaraswamy and Ananda were sent ahead early, Sir Mutu succumbed to Bright’s disease in May 1879 in Ceylon before he could join them.

Mutu Coomaraswamy had quickly established a solid reputation after arriving in England in 1862. In 1863 he starred in a production of the work he had translated, playing 1 to an audience that included Queen Victoria. He lectured locally and on the Continent on cultural and political subjects, and became a member of three or four British professional societies, including the Royal Geographical, and the British Association for the Advancement of Science. To the latter’s Section E Fall 1863 annual meeting he delivered a paper entitled ‘On the Ethnology of Ceylon’; here his path very likely crossed with Wallace’s, who delivered his paper ‘On the Varieties of Men in the Malay Archipelago’ to the same section of that meeting. They both may also have attended various sessions of the RGS during this period, as Coomaraswamy was made a member during the meeting of 11 January 1864, and Wallace had been one since 1854. Coomaraswamy was also present at the 7 July 1873 meeting of the RGS, during which he contributed remarks on Sir Bartle Frere’s paper on Africa; whether Wallace was present is unknown.

That Wallace owned a copy of Arichandra might be explained in a number of ways. He may have purchased a copy after hearing Coomaraswamy speak or getting to know him in the 1860s, or later, in the 1870s. Since it was a bookstore copy, it is less likely it was a gift (though the Coomaraswamy family was very wealthy, and if they had no supply of free copies at hand might easily have purchased one for him). But it is also possible he obtained one much later, from Lady Coomaraswamy, or from Ananda.”

A ‘carefully compiled volume of Shaw’s characters’ (according to the foreword contributed by W.A. Darlington) by Phyllis Hartnoll in 1975, provides the following detail on Pandranath character.

“An elderly Cingalese plutocrat, too much occupied and worried by making money to get any fun out of spending it, though he has a great deal, probably about twenty millions. He comes to congratulate the Prime Minister, Sir Arthur Chavender, on his new programme of reform, saying the City will be solidly behind him. The nationalization of land will mean that he can go through with such schemes as the Blayport Docks reconstruction without having to compensate the landowners, and can also pay his workers less because they will not have any rents to pay to their landlords. Unfortunately the Foreign Secretary, Sir Dexter Rightside, is so enraged by Chavender’s proposals, and the way in which his supporters are ralling to him, that he loses his temper and calls Pandranath ‘a silly nigger pretending to be an English gentleman’; whereupon Pandranath says he will leave England, sever the connection between English and India, and allow ‘the needy British imbeciles’ to perish in their ignorance, vain conceit, and abominable manners.’

Ananda Coomaraswamy’s criticism on the use of ‘Cingalese’ to indicate Ceylonese

Shaw’s confusing use of the adjective word ‘Cingalese’ has to be interpreted as a generic use for Ceylonese, around the first half of the 20th century. Even the great Tamil poet Subramania Bharati (1882-1921) had practised similar usage, in his popular poem ‘Sindhu nathiyin misai nilavinile’. On this erroneous generic usage and misinterpretation, Ananda Coomaraswamy had commented critically in the Nature journal of Aug. 4, 1904 (vol. 70, page 319). He wrote as follows:

“On p.131 of the current volume of Nature, the expression ‘Cingalese fishes’ and on p. 78 of the same volume the expression ‘Cingalese outlier’ are found. The word Cingalese is also used in the ‘Cambridge Natural History’ (Mollusca) to denote a subregion. In the first place the word should be spelt Sinhalese, the form above quoted being a quite incorrect transliteration. In the second place, the adjective corresponding to Ceylon is Ceylonese, the word Sinhalese meaning ‘of or belonging to the Sinhalese race.’

It seems that Ananda Coomaraswamy had anticipated the errors of Subramania Bharathi and Bernard Shaw.

In reviewing the ‘On the Rocks’ play staged by Federal Theatre Company in New York directed by Robert Ross, critic Brooks Atkinson had written, ‘As a Cingalese Prince of commerce, Marvin Williams delivers one of the great speeches of the evening with superb and fastidious contemptuousness.’ [New York Times, June 16, 1938]

Among the two published studies on ‘On the Rocks’ play that I had checked, Frederick McDowell had identified the central character Sir Arthur Chavender (prime minister) as a satire on the incompetence of British prime minister Ramsay MacDonald and his coalition ministry in the early 1930s. Noted American film and theater critic Stanley Kauffmann (1916-2013) had erroneously identified Sir Jafna as ‘one of the ministers is an Indian’. In Shaw’s portrayal, Sir Jafna was NOT a cabinet minister, but an influential businessman who had earned the privilege of attending a Cabinet meeting, unannounced.

Sir Jafna’s name twisted into Dame Adhira in 2011

It is indeed pathetic that a Canadian adaptation of this play by playwright Michael Healey (b. 1963) in 2011, switched the sex of Sir Jafna’s character into that of a woman named Dame Adhira Pandranath. The role was played by Cherissa Richards. This sort of gender switch cannot be considered as offering little highlight to a woman character in this ‘On the Rocks’ play. In reality, among the 17 characters in this play, Shaw had placed 6 women characters (five are named: Alderwoman Aloysia Brollikins, Flavia Chavender, Lady Chavender, Sandy Glenmorison, Hilda Hanways; and an unnamed woman doctor engaged by Lady Chavender). Thus as a Tamil, I’d consider this sort of silly ‘sex and name switch’ by Michael Healey as an insult to Shaw, Sir Muthu and the Jaffna city. Had Shaw been living in 2011, he would have shredded to pieces this particular Canadian production, for having the temerity to stand on his shoulders and taking the liberty to twist the name and sex of one of his fictional characters.

On the etymology of Jaffna

According to Mudaliyar Rasanayagam’s research published in 1926, the earliest mention of the Tamil word ‘Yalpanam’ in Tamil literature is in the Thirupugal hymn of Saint Arunagirinathar, in which he had addressed it as ‘Yalpana Nayanar Pattinam’. Arunagirinathar’s period is assigned to mid 15th century. Rasanayagam also indicates that in the Ceylon maps of Bernard Sylvanus (AD 1511), ‘Insula Caphane’ is inscribed. According to Rasanayagam, ‘This is perhaps the earliest record in which Yalpanam was called Jaffna (Caphane) by the European writers.’ where Caphane is taken as a variant of ‘Jaffane’. Then, during the Portuguese period of the island history, the manuscript of Fr. Fernao de Queyroz entitled ‘Conquista temporal e spiritual de Ceylao (i.e, The Temporal and Spiritual Conquest of Ceylon, 1687) had translated Yalpana Pattinam into Jafana Patao into Portuguese.

Prior to Mudaliyar Rasanayagam, in a 1905 Handbook to the Jaffna peninsula, Katiresu had explained the derivation of Jaffna from Yalpanam as follows:

“The colloquial form of Yalpanam is Yappanam. Now the sounds of Ya and Ja are easily interchangeable. So are those of pp and ff. Thus Yappanam is easily interchangeable into Jaffanam. As soon as it went into a foreign language it lost the Tamil ending m. Consequently it stood as Jaffana. As the result of the natural inclination to mak a name short and sweet the second a was dropped. Tus we have the present name Jaffna, the original Yalpanam being still retained in Tamil.”

One understandable reason, for this change from Yalpanam (correctly pronounced as Yazhpaanam) to Jaffna used by the non-native Tamil speakers from Portuguese days of the island, is that Tamil language has three different ‘L’ sounds. – la (ல), La (ள) and zha (ழ) (please check this youtube video from the Tamil channel, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RMJNV61I9iU). The third and difficult ‘L’ sound which appears in the pronunciation of Tamil (correctly pronounced as Tamizh by the natives) language, also appears in the Yaazhpaanam.

Cited Sources

Coomaraswamy A.K. The word Cingalese. Nature, Aug 4, 1904; 70: 319.

Hartnoll P. Who’s Who in Shaw, Elm Tree Books, London, 1975, pp. 162-163, 243.

Holroyd M. Bernard Shaw, volume 3: 1918-1950: The Lure of Fantasy, Chatto & Windus, London, 1991, pp. 333-344.

Katiresu S. A Handbook to the Jaffna peninsula and a souvenir of the Opening of the Railway to the North, American Ceylon Mission Press, Tellippalai, 1905, p.4

Kauffmann S. George Bernard Shaw: Twentieth-Century Victorian. Performing Arts Journal, 1986; 10(2): 54-61.

Martyn JH. Martyn’s Notes on Jaffna – chronological, historical, biographical, American Ceylon Mission Press, Tellippalai, 1923, pp. 213-214.

McDowell F.P.W. Crisis and unreason: Shaw’s ‘On the Rocks’. Educational Theatre Journal, Oct 1961; 13(3): 192-200.

Nestruck J.K. On the Rocks: Shaw’s political satire still resonates. Globe and Mail, July 10, 2011. https://www.theglobeandmail.com/arts/theatre-and-performance/on-the-rocks-shaws-political-satire-still-resonates/article629335/

Rasanayagam C. Ancient Jaffna, being a research into the history of Jaffna from early times to the Portuguese period, Every Man’s Publishers, Madras, 1926.

Smith C.H. Alfred Russel Wallace Notes 17: More on the South Asian connection. Western Kentucky University – Faculty Staff Personal Papers, Apr 2021.https://digitalcommons.wku.edu/fac_staff_papers