by Velupillai Thangavelu, ‘Colombo Telegraph,’ July 19, 2014

Thirty one (31) years ago on July 24, 1983 Sinhalese mobs executed an orgy of violence that surpassed all other previous pogroms executed in 1956, 1958, 1977, 1979 and 1981.

The events of July 1983 are poignant for the entire Thamil population around the world. Between July 24 and 29, Thamils were systematically targeted with violence in Colombo and many other parts of Sri Lanka.

The pogrom was a backlash by Sinhalese extremists following the mass funeral of 13 Sinhalese soldiers killed in an ambush on the previous day in Jaffna by members of the Liberation Tigers of Thamil Eelam (LTTE). In a deliberate attempt to inflame racial passions the GOSL gave wide publicity to the killings by televising, broadcasting and publishing the news. On the contrary the reprisal killings in execution style of innocent Thamils went unreported in contrast to the wide publicity given to the killing of the 13 soldiers in Jaffna.

Below is a synopsis of how the 1983 riots unfolded with all its fury:

Sri Lankan Governments officials categorized the violence as uncontrollable race riots instigated by the killing of 13 Sinhala soldiers on the night of July 23. However, history and the course of events during Black July illustrate the Sri Lankan Government’s undeniable involvement in the genocidal acts against Thamils.

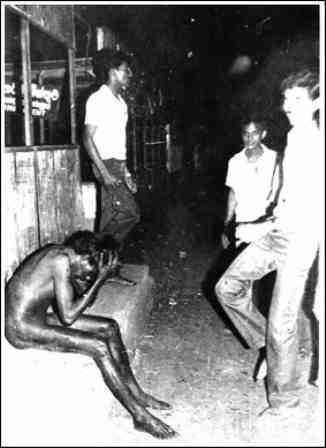

1983 pic by Chandraguptha Amarasingha – A Tamil boy stripped naked and later beaten to death by Sinhala youth in Boralla bustation

July 24 (Day 1): At 1 o’clock in the morning of July 24, the army rounded up hundreds of Thamils in Trincomalee, Mannar, and Vavuniya in the Northeast who had fled the anti-Thamil riots of 1977 and 1981. These Thamils were forcibly taken and left without possessions in the central hills.

Before the riots broke out in Colombo, the army in Jaffna went on rampage in Jaffna. According to the report of the Presidential Truth Commission on Ethnic Violence (1981 – 1984) the army in Jaffna, in revenge for the killing of the 13 soldiers, killed 10 Thamil civilians on Sunday, 24 July 1983. By the evening, the number rose to 51 reprisal killings of Thamil civilians. They were all random killings just opening fire at the whims and fancy of marauding army personnel.

Evidence was placed before the Commission that if the news of these reprisals had been published, the riots may have been avoided. But incredibly, the country’s media went silent on the fact that 51 (Thamil civilians) had already been killed in response to the killing of the 13 Sinhalese soldiers.

In Trincomalee, similar violence broke out as members of the Navy randomly shot at civilians and burnt down Thamil property.

In the evening in Colombo, the state funeral was organized for the soldiers. Thousands of people arrived at the cemetery but the bodies failed to appear. After waiting several hours, the crowd objecting the burial in Kanatte demanded the bodies to be returned to the next of kin. As the large crowd began to leave the grave, a new group of people (identified as government gangs) entered the Borella junction and raised anti–Thamil slogans. As the anti-government cry subsided and anti-Thamil cries became dominant, arson and murdering of Thamils broke out.

July 25 (Day 2): After the midnight lull, mobs were led by people with voter registration lists in hand torched Thamil homes, looted and destroyed Thamil businesses. All traffic was searched, and any Thamils found were killed, maimed, or burned alive. Cyril Mathew, Minister of Industries, was seen directly pinpointing shops to be burned down.

In Colombo, Sinhalese thugs armed with electoral lists and led by Buddhist monks in yellow robes burnt and looted Thamil homes, business and industrial establishments under the very nose of the armed forces. Thamil civilians were hunted down like dogs and killed. Children were thrown into burning cauldron of tar barrels. Clouds of smoke from burning Thamil homes blackened Colombo skies and soon the violence spread to other cities and towns.

Although, policemen were deployed throughout the city they tacitly stood and watched the unfolding mayhem. Witnesses recall lorry loads of armed troops leisurely waving to looters who waved greetings back. Curfew was only declared by the President late in the afternoon after the worst was over. However, the violence continued unabated. Tens of thousands of Thamils, who were homeless, sought refugee in schools and places of worship.

In Welikada prison, 35 Thamil political prisoners who were awaiting trial under the Prevention of Terrorism Act were massacred by Sinhalese prisoners with the complicity of jail guards using improvised spikes, clubs and iron rods.

The violence spread rapidly throughout the country, engulfing towns like Gampaha, Kalutura, Kandy, Matale, Nuwara Eliya and Trincomalee. One town was completely wiped out – the Indian Thamil town of Kandapola, near Nuwara Eliya.

July 26 (Day 3): Government imposed strict censorship of media reporting on the anti-Thamil violence. Word spread of Sri Lanka’s state of disorder as eye witness accounts and photographs taken by returning tourists illustrated the scale of violence. They described how Thamil motorists were dragged out of their vehicles and hacked to pieces while others were drenched with petrol and set alight in full view of the security forces. The International Airport in Colombo was closed. The violence spread to the country’s second largest city Kandy on 26 July. By 2.45pm Delta Pharmacy on Peradeniya Road was on fire. Soon afterwards a Thamil owned shop near the Laksala building was set on fire, and the violence spread to Castle Street and Colombo Street. The police managed to get control of the situation but an hour later a mob armed with petrol cans and Molotov cocktails started attacking Thamil shops on Castle Street, Colombo Street, King’s Street and Trincomalee Street. The mob then moved on to nearby Gampola. A curfew was imposed in Kandy District on the evening of 26 July.

In Trincomalee false rumours started spreading that the LTTE had captured Jaffna, the Karainagar Naval Base had been destroyed and that the Naga Vihara had been desecrated. Sailors based at Trincomalee Naval Base went on a rampage, attacking Central Road, Dockyard Road, Main Street and North Coast Road. The sailors started 170 fires before returning to their base. The Sivan Hindu temple on Thirugnasambandan Road had been attacked.

July 27 (Day 4): 18 more prisoners at Welikada Prison were hacked to death just two days after the prison massacre. Their bodies were piled before the statue of Buddha inside the prison. A total of surviving 36 political prisoners were transferred to other prisons. Rioting continued and the curfew was extended. Witnesses of the violence reported that charred and mutilated corpses of Thamil victims lined the streets of Colombo. In the Central Province the violence spread to Nawalapitiya and Hatton. Badulla, the largest city in neighbouring Uva Province, had so far been peaceful. At around 10.30am on 27 July a Thamil owned motorcycle was set on fire in front of the clock tower in Badulla. Around midday an organised mob went through the city’s bazaar area, setting shops on fire. The rioting then spread to the city’s residential areas where the homes of many Thamils were burnt down. The mob then left the city in vans and buses they had stolen and headed for Bandarawela, Hali-Ela and Welimada where they set properties on fire. The riot had spread to Lunugala by nightfall.

July 28 (Day 5): Vigilantes set up make-shift roadblocks in villages across the island, searched cars and buses for Thamil passengers. In one incident, a Sinhalese mob burnt to death about 20 Thamils on a minibus as European tourists looked on in horror.

After remaining mute and deaf for 5 days President J.R. Jayewardene appeared on television and addressed the nation for the first time since the outbreak of the anti-Thamil pogrom. His speech poured oil into the fire or rubbed salt into the wounds inflicted on Thamil civilians. He fanned the flames of anti-Thamil sentiments by stating that legislation would be brought before Parliament to bar political parties that espouse separation from entering the Legislature and to deprive members of such parties of their civic rights:

‘We are very sorry that this step should be taken. But I cannot see, and my Government cannot see, any other way by which we can appease the natural desire and request of the Sinhala people to prevent the country being divided, and to see that those who speak for division are not able to do so legally.’ There was no remorse and no apology to the victims of the violence from the head of state. On the contrary Jayewardene brazenly justified the orgy of violence by declaring that the attacks were “not a product of urban mobs but a mass movement of the generality of the Sinhalese people.” and that “the time had come to accede to the clamour and the national respect of the Sinhalese people to prevent the country from being divided.”

J.R. Jayewardene made good on the promise to bring in legislation to bar political parties that espouse separation. The 6th Amendment was passed on August 03, 1983. The Amendment outlawed support for a separate state within Sri Lanka and required all Members of Parliament to take an oath of allegiance “to the unitary state” of Sri Lanka.

July 29 (Day 6): Wild rumours started spreading around Colombo that the army was engaged in a battle with the Thamil Tigers. Panicking workers fled in any mode of transport they could find. Mobs started gathering in the streets, armed with axes, bricks, crow bars, iron rods, kitchen knives and stones, ready to fight the Tigers. The Tigers never came so the mobs turned their attention to fleeing workers. Vehicles were stopped and searched for Thamils. Any Thamil they found were attacked and set on fire.

A Thamil was burnt alive on Kirula Road. Eleven Thamils were burnt alive on Attidiya Road. The police found an abandoned van on the same road which contained the butchered bodies of two Thamils and three Muslims.

Thamils in Colombo began evacuating by cargo ship to the Northern city of Jaffna. Hundreds more internally displaced persons waited anxiously for the next cargo ship to transport them to Jaffna.

July 30 (Day 7): Violence was reported in Nuwara Eliya, Kandapola, Hawa Eliya and Matale on 30 July. But elsewhere violence began to subside. That night the government banned three left-wing political parties – Communist Party of Sri Lanka, Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna and Nava Sama Samaja Party – scape coating them for inciting the riots. The banning of the JVP led to another armed uprising between 1987 and 1989.

The orgy of violence continued till August 03, 1983. Although, the Government claimed that the attack on Thamil civilians was a spontaneous backlash by ordinary Sinhalese, but the scale and intensity of the killing sprees belied that claim. There were at least 3 powerful cabinet ministers seen instigating the violence. Some Sinhalese did risk their lives to save Thamil neighbours and friends from the marauding mobs, but the overwhelming majority just looked on.

The 11 days of unmitigated violence propelled Sri Lanka into an era of war and destruction that lasted for 24 years, costing 140,000 lives or more and leaving the economy of the North and East in tatters.

About 3,000 (official estimates 358) lives were lost and more than a 100,000 (75 per cent of them from Colombo) were rendered homeless and ended up in refugee camps. More than 100,000 fled to neighbouring India as refugees. Several thousands more fled the country seeking refuge in the West, including Canada. In sheer scale and intensity the Black July pogrom surpassed all previous pogroms in 1956, 1958, 1977 and 1979.

Thamils fearing persecution by the state on grounds of ethnicity and religion fled the country in droves. They sought refuge in countries like Canada, Europe, Australia and the U.S. The exodus resulting in a million strong Thamil Diaspora perceived by the Sri Lankan government as terrorists and sympathizers of the defeated LTTE. Even after the end of a bloody war in May, 2009 Thamils continue feeling to Australia in boats where they are intercepted and arrested by the Australian Navy in mid-seas.

Today, Northern and Eastern provinces are under the occupation of the armed forces. Sixteen out of 20 Divisions are deployed in the North (14) and East (2). In addition there are 2 Task Forces one each in Kilinochchi and Mullaitheevu. The demand by Thamils to withdraw the army of occupation or reduce its presence substantially has gone unheeded.

The government after much pressure held elections to the Northern Province in September 2013. But the Council with a Sinhalese Retd. Army Major General as executive Governor remains largely dysfunctional. A cold war is going on between the Chief Minister and Council on one side and the executive Governor on the opposite side. As a consequence there are two parallel administrations one under the executive Governor and the other under the Chief Minister. In fact there are three, if we include the Government Agent, Jaffna district.

Black July 83 saw the parting of the ways irrevocably by the Sinhalese and the Thamils politically and psychologically. Since then, the polarization between the Thamils and the Sinhalese has remained antagonistic and the divide widened, especially after Mahinda Rajapaksa assumed office as president in 2005.

The one positive outcome of the Black July pogrom is the rise of Thamil militancy and Thamil nationalism and the demand for an independent state. Though the armed struggle by the LTTE has been defeated, the causes which led to it in the first place remain unresolved.

Last month, there was a repeat of Black July in a miniature form in Aluthgama, Beruwela, Dharka Town and Panandura. This time the target was not Thamils but Muslims who through out the war years supported fully the government war efforts against the LTTE. Now the Muslims believe the latest attack on Muslim homes and businesses is government backed. In fact, Sri Lanka’s Deputy Representative in Geneva blamed Muslim extremists for starting the riots. Further attacks on Muslims cannot be ruled out going by past experience.

As was the case in 1983, one of the main objectives for the attacks is to destroy the emerging economic clout of the Muslim community.