So there is this hangup of mine. I don’t like reading books that everyone is raving about at the time it comes out. So despite many people telling me I must read this book, I took my time and I am glad I did or else I might feel I was influenced by their opinions.

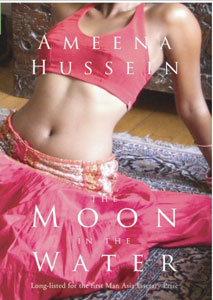

I had read her previous two books and I am a fan. In them she has a distinctive voice and a certain rawness that was appealing. And look at that cover! It is fabulous if not a little risqué.

Because Ameena Hussein is a Muslim, it is understandable that she writes a novel that deals entirely with a Muslim family. A young very modern (living together with her boyfriend, living in a foreign country working, educated abroad – is it realistic, I ask?) Muslim woman comes back to the country when her father dies in a bomb blast. She has one sister and two brothers. She is the eldest in the family. When she comes back, she realizes that she is adopted and that because of some convoluted aspect of Muslim Law she can’t inherit from her father who dies without making a will. She also realizes that she has a blood brother and off she goes to find that brother who has had the most different life from her. She is not upfront about being his sister and I suspect he is falling in love with her and is mad with her for hiding that fact. They part on strained terms but later on start meeting and talking and also seem to be stepping over the boundaries that rule brothers and sisters. Then tragedy takes place and soon after the book ends.

Trained as a sociologist and having worked and studied in Los Angeles, after a short period in Geneva, Ameena Hussein returned to live in Sri Lanka in 2003. She is the co-founder of the Perera Hussein Publishing House which publishes cutting edge Sri Lankan fiction. She divides her time between Colombo and her country home where she grows trees to offset the environmental pollution in printing books. She has published two award winning collections of short stories, Fifteen and Zillij and in 2009 published her first novel, The Moon in the Water.

Trained as a sociologist and having worked and studied in Los Angeles, after a short period in Geneva, Ameena Hussein returned to live in Sri Lanka in 2003. She is the co-founder of the Perera Hussein Publishing House which publishes cutting edge Sri Lankan fiction. She divides her time between Colombo and her country home where she grows trees to offset the environmental pollution in printing books. She has published two award winning collections of short stories, Fifteen and Zillij and in 2009 published her first novel, The Moon in the Water.| The dark side of the moon | |

| Book facts: The Moon In The Water by Ameena Hussein. Reviewed by Wijith De Chickera. ‘The Sunday Times,’ Colombo, February 8, 2009 | |

| With this tale, you may try something new: read it in one sitting. This reader attempted it, and was amply rewarded for his effort. Some three and a half hours after undertaking the endeavour – shaken, stirred and suitably impressed.

The first impression is that this tome encases a ripping good yarn… there’s love, its loss, an unexpected desire, a perplexing identity crisis, the revelation of betrayal, heartache and a resolution that does not compromise the storyteller’s sense of integrity.

Surprisingly for a volume that has been long-listed for the first Man Asia Literary Prize, this work is peppered with colloquialisms and incorporates local idiom cleverly enough to make even more Western oriented readers feel at home… A lexicon of vernacular words flavours this rich goulash: machang, kachal, thada, kaduwa, watte, thraada, maara, vaathey, patas, muspenthu, puduma. An unblinking use of Sinhala verbs promises to add interesting neologisms to the arsenal of contemporary writers in English: chusfy, kusukusufy, ambarennafy! And Sri Lankanisms such as “slowly, slowly”; “hi-bye terms”; “not very hi-fi”; and “So! So! How? How?” are dropped surreptitiously into the water of the narrative without disturbing the repose of the moon… Also entertaining are the interpolation of our familiar argot – “chooti bit”; “I am not sleepy one bit”; accidentally-purposely met”; “ a face as long as Galle Face”; “he went to be a big man” – into the most unlikely conversations. Happy is the reader who can enjoy the firm but funny caricature of our fellow speakers’ ability to render the simple word “nothing” in a myriad meaningless ways… Indeed the author’s love of language and facility in reflecting its nuances is so “b-i-i-i-g” that one cannot forbear to cry “Stop! Stoooorp!” However there’s much more than wordplay and linguistic experimentation in this gripping piece (although memorable one-liners abound: p. 10, p. 12, p. 97, etc.). Evocative language illustrates nostalgic landscapes of a common past and shared present to make events more tangible to future readers. Technical innovations like the interpolation of letters to carry the narrative forward; and an extract from a notebook maintained by the protagonist, which underline one theme of the tale – hybridity – serve well… Satirical humour lightens the heavier themes that lie beneath the initially placid surface. We nod smilingly near the opening of the narrative when the prospective bride’s parents interpret a prophetic warning to keep their daughter away from a black man to mean one with dark intentions! The funny-clever first paragraph on page 14 is a sugar-coated capsule that makes the bitter pill that is to come easier to swallow…Social commentary is undertaken with a vengeance – but is executed with a light hand… from comparisons between historic Andalusia, to which the protagonist goes, and hysterical Beruwela, from which many of her compatriots come… and the versatility of the author is reflected in the breadth and scope of the topics that she chooses to subject to her telescope: sex, love, sibling rivalry, societal hypocrisy, religious rigidity, courtship peccadilloes… Sexual and marital mores as practised by our society in general but a certain community in particular are placed under a more penetrating microscope. The hypocrisy that often accompanies mourning for loved ones lost receives short shrift, albeit couched in charming villanelles that first amuse, and then seek to edify. So when suspect or somewhat contrived romantic episodes interlude (as in the last paragraph on p. 21), one must be prepared to read the developments in context. For the ostensibly forced nature of this character’s actions seem poignant in hindsight, when the full flowering of her personality reveals unplumbed depths to her being. For no one changes her mind with such panache as Ameena Hussein’s Khadeeja Rasheed – although “sometimes, she [only] wanted life to be simple and uncomplicated, and for someone to understand her…” The irony is when she is drawn to “the sigh of [another] Moor”, whom only she is slowly beginning to understand… Seemingly inconsequential anecdotes – such as the card game for the highest stakes, where the loser forfeits his or her single state – enliven the dullness of religiously regimented households of faith. In the larger context of a tightly spun web that vibrates towards a resonant conclusion, this seems an acceptable literally device. And by the way, the tales are told with such authenticity that one suspects some of the more colourful incidents may be drawn more from reality – experienced or heard related – than the imagination. The author’s forgiveness is craved, if this craven assumption proves wrong? In the end, though, when the darkness is done, and the rawness of the central story doesn’t ripen into quite the redemption we hope for, the ravages of time and nature reveal that this is the story of a peculiarly Sri Lankan generation – where, though the moon is out and the tide is unfair, we are all as on a darkling plain… swept with confused alarms of struggle and flight, where ignorant armies clash by night. |