by Roy Ratnavel, Viking/Penguin Random House, Canada, 2023, 260 pp, US$27.00

by Sachi Sri Kantha, October 28, 2023

Roy Ratnavel

This book of memoir by Roy Ratnavel (born 1969), a naturalized Canadian of Sri Lankan Tamil descent, has achieved bestseller status in Canada this year. The memoir has 12 chapters altogether, among which the first three (in 59 pages) covers Roy’s life in Sri Lanka. Excluding the final chapter titled ‘The Future’, chapters 4 to 10 cover ladders of success the author climbed in Canada, as an immigrant in 1988, from the mailroom boy, a mentee of Robert C. McRae (the founder and CEO of the company Roy joined), the traveling salesman, as a father and to a leader. The penultimate chapter is titled ‘The Canadian’. The final chapter entitled, ‘The Future’ provides some self-introspection as well as the lives of Sinhalese and Tamils in Roy’s country of birth, including thoughts about his late father.

Ratnavel Sr was one of the more than 5,000 Tamil homicide victims of the Indian Peace-Keeping Forces (IPKF) in Sri Lanka. He was killed on April 21, 1988 in Point Pedro, at the age of 53, in front of his wife Indra. This happened only three days after Roy bid adieu to his parents at the Colombo (Katunayake) International Airport. Ratnavel Sr. had given Roy the last hug at the airport saying ‘In Canada, you will have opportunities that I never had’, in addition to one hundred US dollars.

That Roy was able to establish a new career as an immigrant in Canada, after being a Tamil detainee in the notorious Boosa camp in 1987 is a remarkable achievement. And that, that he has gotten the courage to write about his experiences deserves applause. I was deeply touched by his descriptions in three pages in chapter 1 ‘The Prisoner’. Two paragraphs from these three pages are reproduced below for sampling.

“There were about 2,700 of us. They split us into fifty-two groups and assigned each of us a prisoner number. I was prisoner #1506. [Note by Sachi: The book’s main title originates from this.] The primary objective of the imprisonment was to coerce as many of us as possible to confess to being members of the Tamil Tigers. The government could then claim to the world that the prisoners were in fact insurgents, not innocent young boys. The coercion to achieve this goal came in many different forms. Intimidation and threats to our families were the mild versions. Then there were various forms of torture – severe beatings with sand-filled plastic pipes, electric shocks on our private parts, and lashings by barbed wire to the upper back. At night, some men screamed at the top of their voices, some wailed, some sobbed quietly, while others argued over sleeping space. Exasperated, driven mad, people didn’t cease quarrelling and telling each other to go to hell.

If you were fit and in good shape, then you were the unlucky one. They immediately assumed that you were a Tamil Tiger who had combat training. There was one man named Ananthan, maybe in his mid-thirties – a mechanic from our town who was well-built. They beat this poor soul to a pulp. He was bleeding through his mouth for days; he couldn’t even see because his eyes were closed shut from the beatings. He couldn’t walk for weeks. He had to be carried on a gurney made from an empty sack; two men grabbed the corners. And someone had to feed him. I still think about hi. He was in very bad shape. I never found out if he made it out alive or not…”

There is corroboration for what Roy experienced in Boosa camp between June and July 1987. Mervyn de Silva courageously published a one page brief report by another Tamil detainee, S.Velupillai in his Lanka Guardian [Oct 1, 1993, p. 20] magazine. Here are excerpts from this report.

“ ‘Operation Liberation’ commenced on May 26, and ended on May 31, and resulted in over 1,000 deaths and 2,000 arrests in Vadamaradchy on its liberation from the LTTE.

We, the captives, were chained and shipped to a makeshift detention camp in Galle, though our destination, according to our papers, was to be the notorious Boosa Detention Camp. Later, we came to know that Boosa was already full.

We were confined to a warehouse turned into a detention camp, adjacent to the port of Galle, about 200 metres long, and 20 metres wide. There were 6 latrines, outside the camp. At a time detainees would be led out at gun point to spend 6 minutes in the latrines. Most of us had no option other than defecating and urinating into a gutter deep inside the camp. The gutter overflowed. We wallowed in our own faeces and urine that flowed from the gutter, under our feet, towards the centre of the camp which teemed with worms and flies, vomit and spittle. There were no baths. None of us had bathed or changed for days. Both the camp and the inmates stank…”

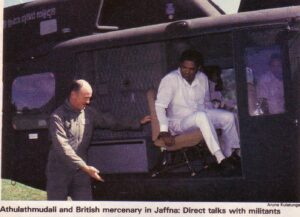

Minister Lalith Athulathmudali (in whites) arriving at Jaffna (Asiaweek, Feb 8 1987)

Whereas the detainee Velupillai had an encounter with Minister Lalith Athulathmudali (1936-1993), the architect of such Nazi-minded treatment of hapless innocents, the author of this book was rather fortunate to have an encounter with the second wife of Athulathmudali – Srimani (1946-2004), who was NOT a politician in 1987. She was sent on a ‘photo-op’ visit with the Tamil detainees. Luckily for Roy, Srimani turned out to be a messenger angel, conveying the location of Roy to Col. Dudley Fernando, a family friend. Via the attestation of this kind-hearted Sinhalese military man, Roy got released from detention.

Both Roy and Velupillai provide a figure of nearly 2,500 young Tamil detainees during Athulathmudali’s ‘Operation Liberation’ campaign of 1987. One wonders what happened to the other 2,500 odd young Tamils? How many would have died? How many would have lost their minds and are still living as ‘dead bodies’? How many would have their genital organs crushed and damaged? How many are still living in Sri Lanka? Roy mused in one line, ‘Statistics are human stories with the tears washed off, I remember hearing once.’

I have a confession to make. Roy’s parents were my kin. I know Roy’s mother Indra well. Her maternal grandma and my maternal grandma were siblings. This kinship makes Roy a nephew to me; but I have yet to meet him face to face! Roy’s memoir is a paen to his parents (especially his father Ratnavel Sr. (Appa/’old man’). Roy was open in presenting his father as an ordinary Eelam Tamil man, with the nerves, weaknesses and biases of the 20th century. I liked the sentences which appear in p. 55. “But for all his progressive, generous ideas, my Appa held to the belief that the parent was always right, no matter what. My (elder) brother and father had many disagreements. Instead of a bridge, they built a wall between their relationship.”

Also of interest to me was Roy’s sentiments on visiting his father’s old flame in Colombo during his return trip to the island in 2002. The sentences about this meeting were humorous as well as a friendly jab in the shoulder of his dead father. “I just wanted to know more about him. Her name was the same as my mom’s: Indra. Damn the old man planned everything perfectly, I thought. Years after Appa ended the relationship, she was briefly married and never had kids of her own. Now I understood why she was loving toward me, touching my cheeks with her open palms as she spoke…”

Also of interest to me was Roy’s sentiments on visiting his father’s old flame in Colombo during his return trip to the island in 2002. The sentences about this meeting were humorous as well as a friendly jab in the shoulder of his dead father. “I just wanted to know more about him. Her name was the same as my mom’s: Indra. Damn the old man planned everything perfectly, I thought. Years after Appa ended the relationship, she was briefly married and never had kids of her own. Now I understood why she was loving toward me, touching my cheeks with her open palms as she spoke…”

Author’s thoughts about his current success in Canada are summed up in sentences like, “…not only was life unfair – which I already knew – but that it could never be fair. It also taught me that the world was grey. Life will give you what you fight for, once and for all, if only you could find out what you are capable of – and I did. I never negotiate when I’m on my back foot: I always hit first. That’s how I landed this mailroom job. I always refused to allow circumstances to define me and my dignity and destiny.” Using his gut instinct for survival and success, in a span of three decades, Roy was able to raise himself as an executive at Canada’s largest asset management company – CI Global Asset Management. Like a dutiful husband, Roy has recorded the advice and support received from wife Sue (Sujantha) for his professional success, at specific growth periods of his career.

Occasional name dropping of Hollywood celebrities (I guess, angling a promotional option for a movie) couldn’t be avoided in this memoir. The author mentions “I also had the opportunity to meet many Hollywood celebrities during my travels – the likes of Samuel L. Jackson, Robert Duvall, Ben Affleck, Sean Penn, Billy Bob Thornton and Matt Damon. If this book were ever made into a movie, I’d like Matt Damon to play me. We are similar in stature…” If so, readers like me would have been pleased to see some more ‘meat’ served in the text, about these casual interactions with celebrities.

I can comment only about two Sri Lankan Tamil celebrities included in the book, whom I have met personally. One was journalist Reggie Michael, and the other was nonagenarian politician Chelliah Rajadurai (b. 1927) from Batticaloa. Both receive mention from the angle of Ratnavel Sr.’s thoughts. About Reggie Michael, Roy writes that his dad “enjoyed Reggie Michael’s columns; he respected his comments and thoughts relating to complex global issues and considered him a credible, critical commentator of contemporary political events.” On the contrary, Ratnavel Sr.’s opinion on Tamil politician Rajadurai was negative. Roy writes, “This politician was famous for switching parties to land Cabinet posts, and he betrayed Tamils for his personal benefit along the way. Appa thought he had the IQ of a plant.” Well, in my contrasting view, Mr Rajadurai do not deserve such a harsh criticism. As I had noted 30 years ago, Rajadurai fell victim to the North vs East branding among Jaffna Tamils. “After the death of S J V Chelvanayakam in early 1977, Rajadurai’s political fortune as a Tamil leader took a bad turn. He misjudged the mood of the young Tamils. Now in hindsight (after the passing of the Amirthalingam wave), I feel that Rajadurai’s contributions to Tamil nationalism and literature in the East Eelam of the 1950s and early 1960s need re-evaluation. Whatever may be his misdemeanors in the 1980s, Rajadurai did earn the trust of Chelvanayakam as well as the friendship of MGR and Kannadasan in Tamil Nadu, way back in the1950s. One couldn’t have been such a bad guy to be misjudged by three beloved Tamil leaders.” [https://tamilnation.org/forum/sachisrikantha/93writers.htm] Roy does mention about his dad’s appreciation of poet Kannadasan’s lyrics. I also mention that it was the same Rajadurai, who invited the young Kannadasan in 1950s to Eelam and served as his host. As such, Ratnavel Sr.’s jibe that Rajadurai ‘had the IQ of a plant’ was ill conceived at best.

For some additional information to prepare this review, I asked Roy following questions, and his responses received by email are reproduced below:

“Q: From your description, I gather that you were picked up in Point Pedro, after the Vadamarachchy campaign around May 1987, and got released after July 29, 1987. Totally, you would have spent a little over 3 months in Boosa camp. Were your genitals manhandled during torture, in any form?

A: Just a little over two months (I was arrested at the end of May and was released a few days before the Indo-Sri Lanka Accord.). Mostly severe beatings. But on two occasions I’d had electric rods used on my testicles.

Q: When did you first think about writing this book, as a tribute to your father?

A: In my mid-30s, when I became a father in 2005.

Q: Who are your favorite authors (living or dead), whom you admire? You can mention two or three.

A: Ernest Hemmingway, George Orwell & Michael Lewis

Q: What is your favorite book? You can mention two or three.

A: ‘The Old Man and the Sea’, ‘For Whom the Bell Tolls’, ‘The Undoing Project’.

Q: I noted that you had dedicated the book to ‘freedom and democracy’. Can you expand a little? These two words (though currently in fashion) are so abstract and mean different things to different folks. Personally, I consider ‘democracy’ is a nasty word of abuse by many, not only by politicians – beginning from Churchill (who was a racist bully along the same lines of Hitler). I hate to hear this word, pouted by every Tom, Dick and Harry and dumb journalists. How do you define it?

A: It is far easier to denounce freedom than to attain it. I have experienced this firsthand. While people in many parts of the world are seeking freedom and liberty, I’m witnessing the people in the Western nations slowly eroding theirs. I saw this, especially during COVID. To me, this is very troubling. Freedom of speech is paramount, and it is currently under attack. It is my view that free speech is being sacrificed at the altar of political correctness—and our society is being dismantled by a group of fascist, vengeful, radical activists. It’s always easy to criticize freedom, democracy, and capitalism while enjoying the associated benefits of them.

Against this backdrop, I believe it is important to protect these values from the dark forces. True democracy isn’t perfect, and it can lead to mob rule and the tyranny of the majority, as we have seen in Sri Lanka. But a democracy with proper guardrails (constitution) can produce a ‘just’ society for all. In that sense, I prefer a constitutional republic. Democracy is flawed, but it’s still better than every other system I know of. Even with its warts and all, I will take democracy over an authoritarian system any day. Hence, the book was dedicated to freedom and democracy. My appreciation for both is boundless. They are non-negotiable human values. We all need to die on this hill.”

The text is supplemented with 23 photos of Roy and his family members, the kind hearted Sinhalese family of Col. Dudley Fernando and his wife aunty Swarna, as well as a few non-Sri Lankan pals and mentors of the author in Canada. An 8 page index, somewhat incomplete, also adorns the book. A minus point is that the author could have omitted random sprinkling of cuss words, blasphemy and the slang phrase ‘old man’ to refer to one’s dearest father in the text; though a current fad in the West now, the use of such was cautioned against by that great Tamil poetess Avvaiyar in her Aathichuudi primer verses (cited on page 67).

In sum, I’d recommend this book as a worthy contribution to the Eelam Tamil literature of this century. It deserves to be translated into Tamil and Sinhala languages as well.

*****