by Raisa Wickrematunge, @raisalw, ‘Shorthand Social,’ no date, accessed September 7, 2016

It all started when Malaka* and Rohan* (names changed to protect identity) went to meet relations in Wattegama. Returning from the visit, they saw two policemen making off with their motorcycles, which they had parked on the main road. They confronted the officers, who began assaulting the two men with iron rods. Malaka and Rohan were taken to the Wattegama police station, where they were assaulted once again. When Rohan was admitted to hospital, his leg was broken in 5 places. Fearing he might lose his life, the doctors transferred Rohan to the Peradeniya hospital, where he remained for around 9 months, during which time he underwent 5 surgeries. The two policemen also promptly admitted themselves to hospital and filed charges against Rohan, resulting in him being chained to his hospital bed.

Such delays are par for the norm, says Father Nandana Manatunga, the director of the Human Rights Office – Kandy, who handled Rohan’s case. In fact, there have been no cases filed by the Attorney General’s Department against the police or armed forces under the 1994 Torture Act for the past 10 years, due to an order from former President Mahinda Rajapaksa, as the country was grappling with civil war.

At the moment, Father Manatunga is dealing with around 56 complaints of torture in court – although he has handled as many as 98 incidents in the past 5 to 6 years. The delay in judgment comes due to heavy caseloads. The High Court in particularly convenes around three to four times a year. Often, lawyers might not be present, or a vital document might be missing, leading to cases being postponed. This is true for many offences, Father Manatunga points out.

While the system is beset with delays, people are still being tortured – even now, under a Government promoting good governance. Father Manatunga is handling the case of 36 year old Shanthi* (name changed to protect identity), a woman currently being held in the Bogambara, Dumbara prison in Kandy. She has been severely tortured – hung from the ceiling, her clothes torn, and chillies rubbed on her face and body.

Shanthi is the prime suspect in a murder case – but she vehemently protests her innocence. She is accused of killing her ex husband, though her parents attested that she was at their house at the time of the murder. However, she was called in to the Gampola police, then transferred to Nawalapitiya police by vehicle. “In that space of time, they had already decided she had committed the murder,” Father Manatunga said. She was tortured by 7 police officers for almost 2 days. Father Manatunga is currently filing bail applications for her.

The fact that incidents of torture are frequent, and ongoing, has been documented by several bodies, notably the International Truth and Justice Project, and Human Rights Watch. They report hundreds of firsthand accounts, many of them post-war, of abduction, torture and sexual violence. In most of these reports, the finger has been pointed at police and military personnel.

“The police routinely torture people as a way to extract information, or conduct an investigation,” human rights activist Ruki Fernando said, speaking to Groundviews.

“It appears that they think it is the best, or fastest way to investigate… and I think this idea is even reinforced by sections of society, who think that beating up someone who is alleged to have committed a crime, especially where there is clear evidence, is justified outside the judicial system.”

The fact that torture is routinely used by organisations such as the Terrorist Investigation Department (TID) has been well-documented particularly with the release of the UN Human Rights Council resolution on Sri Lanka and the recent visit of the UN Special Rapporteur on torture and other cruel, inhuman and degrading treatment or punishment, Mr. Juan E. Mendez .

“Some of these victims who I have spoken to personally, are scarred for life, and mentally traumatised. Others are physically incapacitated, and cannot find work. The effects of torture are lifelong.” Fernando says.

Often, victims flee the country, but the unlucky few who do not receive political asylum and are deported back face further intimidation, often resulting in beatings.

“I think one major problem is that the culprits are not held accountable. Not just the actual implementers of torture, but those who know that it is being practiced, and allow it to happen. For instance, the OIC in charge of a police station is directly responsible,” Fernando pointed out.

This could be changed with a more effective legal system. “Freedom from torture is a non-derogable right. Certain things can be curtailed in a time of war via Special Assembly. However, torture is not allowed under any circumstances – be it floods, tsunami, war or terrorism,” Fernando says.

So why is the legal system falling short?

Attorney-at-law Ermiza Tegal says part of the problem is a lack of urgency.

“The system is broken in many places.”

Tegal is currently handling around 6-7 cases – that’s without counting the hundreds of other cases being handled by other organisations. In many cases, lawyers like her are on the ‘back foot’ filing fundamental rights cases simply asking for an acknowledgment that torture has occurred.

Many organisations have also begun filing civil rights cases directly against the police officers and state officials themselves – which entitles victims to ask for compensation for loss, including for costs of medical bills.

However, pursuing these avenues is beset with issues. For instance, the quality of the judicial medical reports provided are often questionable. “There have been allegations made that the police have influenced the judicial medical officer so that the report hasn’t been recorded properly.You say you were beaten to a pulp, and the judicial medical officer records you have a small scar on your left wrist, for instance. That makes your story less believable,” Tegal says.

In addition, victims often find it difficult to come forward, simply because they are essentially going up against the police and the state. There have been instances when Tegal has had to file affidavits on behalf of her clients, as policemen have visited victim’s homes, or even sent henchmen on their behalf, to threaten victims into withdrawing their cases.

There is no physical protection for those who are threatened in this manner – the only thing Tegal can do is obtain an order from the Supreme Court, restricting the officer concerned from contacting the victim. “We have to trust that these people fear the law and its consequences.”

In this sense, stronger whistleblower protection is required. The setting up of a dedicated police unit for protection, however, would take time and requires the Government to allocate funding towards it.

The costs of litigation are often high and subject to delays. Many of the fundamental rights cases Tegal handles have been ongoing for between four to six years, even though the constitution states that Fundamental Rights cases should be settled within 2 months. “The court strictly observes the one month period when a litigant is supposed to come to court, but doesn’t observe the 2 month period for finishing a case.” The one month period presents a further barrier – often, victims are ignorant of the law and uncertain where to turn.

“There’s a need for sensitivity and training to get people out of this mindset of protecting state institutions. The only way we can improve state institutions is if we expose the bad practices, so the state can correct them.”

Independent Commissions too could do more in terms of exerting pressure. Currently, the Human Rights Commission has the mandate to visit police stations and verify whether torture is occurring. However, it does not do so at present, perhaps due to lack of manpower and resources. On occasion, they do call police stations when a complaint is received to deliver a warning – which in itself has proved effective, when it is used.

Once again, there are time lags – the Commission can take up to a year to try a case. With long time lags, police aren’t being held accountable for their actions, Tegal says.

The recently appointed National Police Commission too, now just 6 months old, have said they need time, particularly as dealing with complaints against police officers is only a small part of their mandate. “There is no sense of urgency to address this particular issue.”

Currently, the Commission does plan to put a new monitoring system into place, which would track complaints against each police station. The President also recently issued a directive to police and army officers, where there will be no torture or humiliation of terror suspects arrested under the PTA. However, promising though these steps are, it is clear that they are yet to trickle down to ground level.

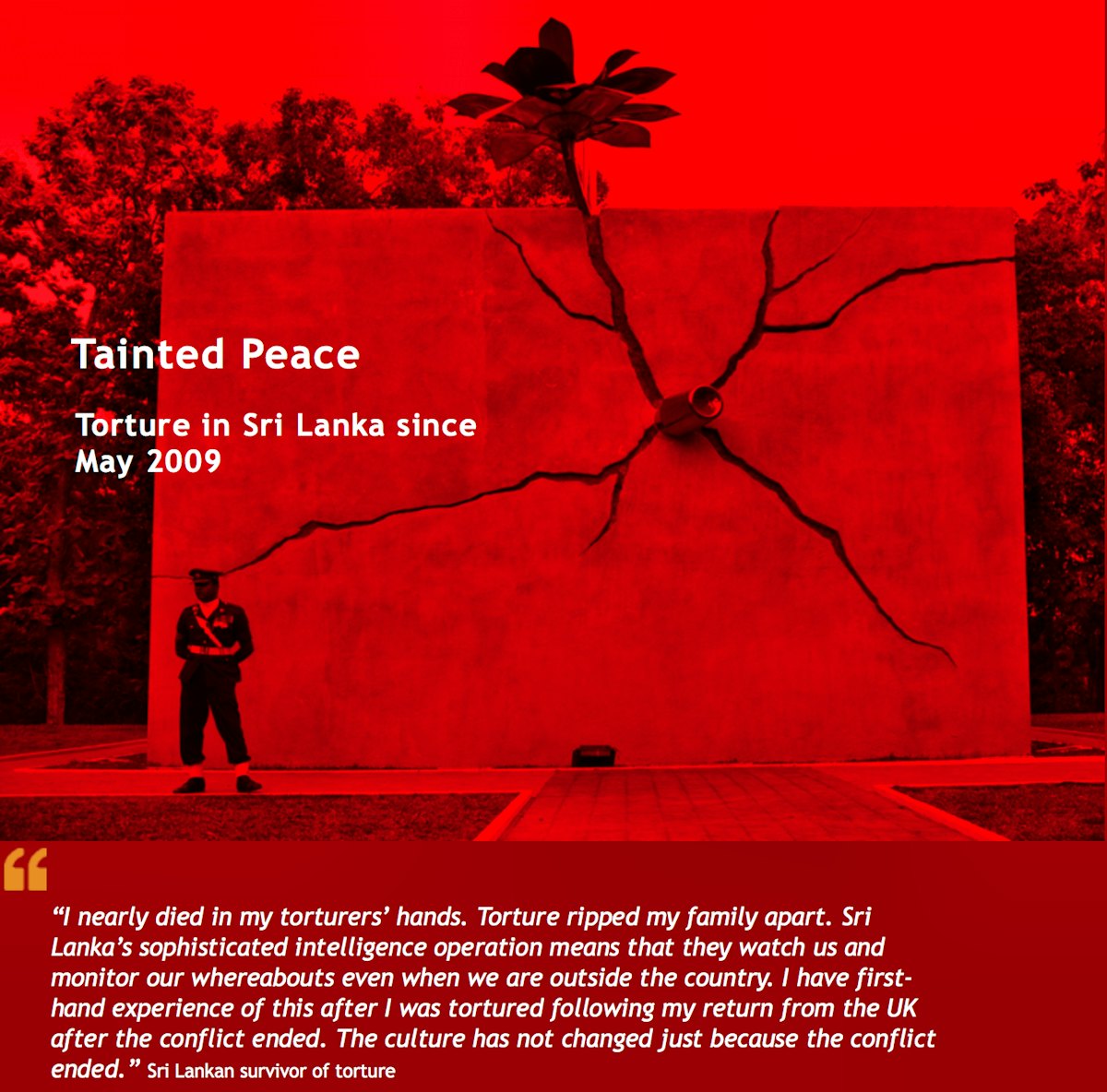

Freedom From Torture (FFT) reported that Sri Lanka is its top country for referrals for the past four years.

“Our clients describe appalling levels of harassment and mistreatment,” Ann Hannah, International Advocate and Researcher, FFT said.

The numbers are staggering – 248 cases of people tortured since the end of the war in 2009, and a further 17 referrals since January 2015, after the Presidential elections, according to FFT. “These numbers illustrate the desperate need for reform in the police, military and security forces,” Hannah said.

The Human Rights Commission Sri Lanka has received 311 complaints at their Head Office and a further 102 at regional offices in 2015 alone. In the first three months of 2016, the HRC has already received 48 complaints at their head office and a further 5 at their regional offices, according to Commissioner Ambika Satkunanathan – higher than the figures reported by FFT.

Freedom From Torture says that in the past, the government has simply rejected evidence of ongoing torture, which the body has recorded intwo previous reports, although the recent state-supported visit of the Special Rapporteur was a positive sign.

FFT wants to see full implementation of the 2015 UNHCR resolution, (including an internationalised justice mechanism) and a torture prevention programme for the military, police and intelligence services.

“It is imperative that the Sri Lankan government now works with international allies to create and implement a prevention programme that can end the culture and practice of torture. Every new case of torture that comes to light undermines government progress on political reform and transitional justice,” Hannah said.

Suspected torture cell. Photo courtesy Tamil Guardian

https://social.shorthand.com/raisalw/3ge03UdC7c/a-broken-system