Not Manusmriti, British—caste system in medieval Tamil Nadu solidified after Cholas fell

by Anirudh Kanisetti, ThePrint.in, March 24, 2024

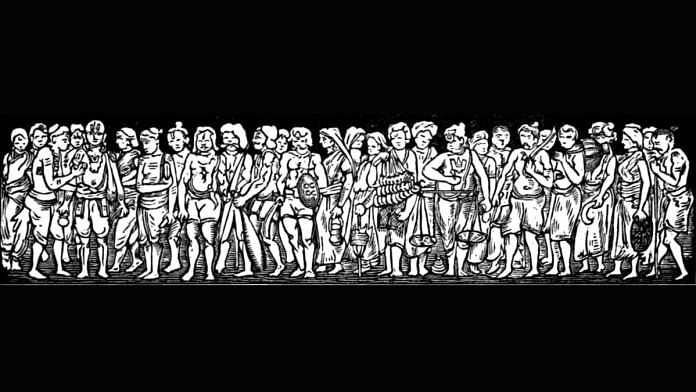

Middle castes reveal a complicated social history. Caste is rooted in politics, not just religion

Caste in medieval south India

Here are some caveats. I don’t wish to make overarching generalisations about the horrors of caste, so I will focus on one part of India: Tamil Nadu, from the late 10th to the 13th centuries CE. This region has tens of thousands of inscriptions preserved on temple walls, made by a huge cross-section of society. This gives us a pretty good sense of how castes actually evolved and what they wanted, instead of the usual debates of “Manusmriti says this” or “British are to blame for that”.

Inscriptions referenced below come from the Epigraphia Indica (EI), Annual Reports of South Indian Epigraphy (ARE), and South Indian Inscriptions (SII).

What do the medieval Tamil inscriptions tell us? First, it was primarily the top and bottom of the caste system that was fixed—and even then, only relatively, and with local variations. By far, the main recipients of land and labour resources from the 10th–12th centuries were Brahmins, considered to be the most ritually pure. Thereafter the focus shifted to temples and mathas, both frequently (but not exclusively) Brahmin-dominated. Royal dynasties like the Cholas made enormous endowments, inviting hundreds of Brahmin families to settle on fertile agricultural land, either already cultivated or ready to reclaim.

But it was not just royals who gave these gifts: so did Vellala agriculturists and aristocrats, generally considered a “pure” Shudra caste. And while Brahmin landlords often received preferential tax rates, they could not entirely avoid it, and there were situations where they were forced into bankruptcy by royal demands.

Also present in the inscriptions are Paraiyar or Pulayar, today Scheduled Castes in Tamil Nadu. In the 11th century inscriptions of the great Brihadishvara temple in Tanjavur, Paraiyar are mentioned as living in hamlets segregated from Brahmin settlements. They also had to use separate cremation grounds. It’s not clear whether they were considered “untouchable” at this early date, but clearly they were segregated and subjugated for agricultural labour. There are occasional mentions of Paraiyar military officers who made temple grants, especially in the far south of Tamil Nadu. But by the 13th century, Paraiyar were oppressed to the point where they were considered “polluting”. Aristocrats’ temple inscriptions curse their enemies as “lower than the Pulayar who cuts grass for my horse”, or that their “wife will be given to the Paraiyar”.

Also read: Buddhism has just been reduced to anti-Brahmin thought. But it shaped Hindu reforms too

The middle castes

So the top and bottom of the hierarchy became more fixed. But what about the middle? Here we see some unexpected trends, not conforming to “Hindu” scripture. Temple donations were fairly diverse. In the beginning of our period, shepherds and washerpeople—both considered lower castes later—gave frequent gifts to temples, usually ghee or cash for holy lamps. So they originally had access to temples and were not considered “impure” in the early centuries.

As Chola power exploded across South India in the 11th century, landowners and military people became far more prominent in society. One major class of donors were people called Pallis, former hunter-gatherers from the hills who gained power as Chola mercenaries. The descendants of Pallis led powerful aristocratic houses, including the Kadavaraiyar and the Sambuvaraiyar; some claimed descent from Vedic sages.

Why this change? Wealthy and influential groups—initially warriors, then traders and artisans—often lobbied for both ritual and social status. But success depended on local influence. In 1168, for example, a group of Rathakara artisans, wealthy from temple commissions at Tiruvarur, got local Brahmins to give them the right to perform some Vedic rituals. But in Achalpuram village barely 60 kilometres away, artisans were far from affluent. Here, Vellala cultivators got Brahmin landlords to confirm their right to exploit artisans and shepherds. If one group wasn’t affluent enough in a locale, it could easily get muscled down by others. The middle castes were competitive about status: their future prosperity depended on it.

Also read: How Shiva and Narasimha worship assimilated Adivasis in Andhra Pradesh

From local to regional

In the 13th century, the Chola empire collapsed in crisis. At this time, large coalitions of social groups took command of the situation, taking collective decisions on local taxation, temple donations, and irrigation. These coalitions spread across multiple villages, towns and locales. It’s here that we can speak seriously of a “caste system”. Instead of having positions based on local politics, the coming together of many groups forced hierarchies to be worked out at a regional scale. We now see inscriptions carefully using terms like varna and jati, and attentive lists of communities and hierarchies. This was a massive social revolution, a direct response to political crisis. It was precisely when the Chola empire declined that caste emerged as a new sociopolitical order. Interestingly, in this new order, aristocrats, landlords, and merchants sometimes took precedence over Brahmins. Ritual status wasn’t the only determinant of caste hierarchy: wealth and influence were central.

But while these groups continued to jostle around, Paraiyar across Tamil Nadu were increasingly forced to the bottom of the hierarchy, where they remained for over half a millennium—well into the colonial period. The 1871 British census of Chingleput district found that 24 per cent of the population were Paraiyar and 19 per cent were Pallis, both earning little more than a bare subsistence. By that point “Palli” had become a derogatory term, and the community fought in the 20th century to be referred to as “Vanniyar”.

What we’ve examined is just three centuries of history. After the 13th century, populations, cities and global contacts grew. So there was even more expansion, consolidation, and lobbying in the middle castes. So powerful were Tamil caste coalitions that they could even force the mighty Vijayanagara Empire to the negotiating table. Some martial castes lost out as new ones arose, turning the Palli/Vanniyar from landlords to labourers. New trading communities like the Chettiar emerged, making colossal profits in new markets. Landless peoples gradually became more and more exploited, until they finally gained access to education and democracy, freeing them at last from traditional local hierarchies.

Also read: South India’s Jain goddesses you haven’t heard of: Establishers of dynasties, fierce protectors

Binaries don’t fit the caste system

When it comes to caste, neither India’s ascendant Right nor its beleaguered Left gets social history right. A few weeks ago, a Right-wing word salad argued that the caste system as practised today was a “Christian colonial artificial reordering”. The Left, on the other hand, sees caste as coercively imposed by Brahmins and kings through Hinduism. From this point of view, caste, once imposed, was essentially unchanging, conforming to Brahminical scripture.

Yes, the British made caste integral to the colonial legal system. But that was due in part to their 19th century Brahmin collaborators, at the time considered representatives of “Hindu” society (which the Right often forgets). As a result, early ideas of caste history were Brahmin-dominated, relying on ancient texts written primarily by Brahmins.

But, against the Left position, there’s little historical evidence that premodern states could enforce what these texts demanded. In medieval Tamil Nadu, more than the State, it was society that made caste. In particular, middle-caste coalitions and aspirations shaped Tamil society for centuries. In 1947, Dr BR Ambedkar quite presciently noted that OBCs would determine the future political history of India. The message, it seems, holds as true now as it did then— and was just as applicable a thousand years ago.

Anirudh Kanisetti is a public historian. He is the author of Lords of the Deccan, a new history of medieval South India, and hosts the Echoes of India and Yuddha podcasts. He tweets @AKanisetti. Views are personal.

This article is a part of the ‘Thinking Medieval‘ series that takes a deep dive into India’s medieval culture, politics, and history.

(Edited by Theres Sudeep)