by Raffi Khatchadourian, ‘The New Yorker,’ January 5, 2015

These days, if a stranger, a shopkeeper, a person offering directions learns that you are Armenian and of Diyarbakir ancestry, you will be ushered into a home, welcomed with tea, treated like a long-lost relative deserving honor. You will be hemşerim: a person of this place.

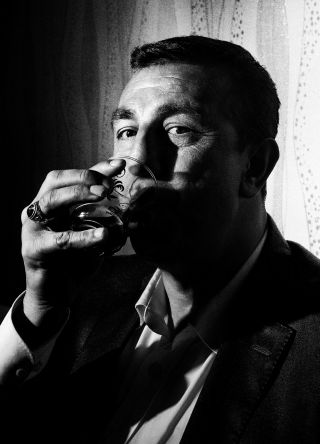

When I met with Abdullah Demirbaş, the old city’s mayor, he had just completed his second term, and he was between political appointments. Demirbaş is Kurdish, and it quickly became apparent that the story of Sourp Giragos’s revival was inseparable from the interweaving narratives of political violence that bound together Armenians, Kurds, and Turks for more than a century. The municipality’s welcoming atmosphere, and its willingness to challenge orthodoxies about the genocide, is in many ways a Kurdish story.

In 1915, in Diyarbakir, Kurds were among the main executors of the genocide; members of prominent Kurdish clans helped plan the massacres for the Ottoman bureaucracy and grew rich by the seizure of property. In the countryside, Kurdish tribal chieftains carried out the killings with pitiless savagery. But then, not long after Mustafa Kemal Atatürk formed the modern Turkish republic, the Kurds themselves became the objects of Turkification, as the state initiated a process to eradicate their culture…

More at http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2015/01/05/century-silence