by Gauri Bhatia, CNBC, New York, April 25, 2016

Situated almost in the middle of the Indian Ocean, there is no escaping Sri Lanka’s centrality.

The country lies just a few nautical miles away from the super-busy east-west shipping route, through which an estimated 60,000 ships pass every year, carrying two-thirds of the world’s oil and half of all container shipments.

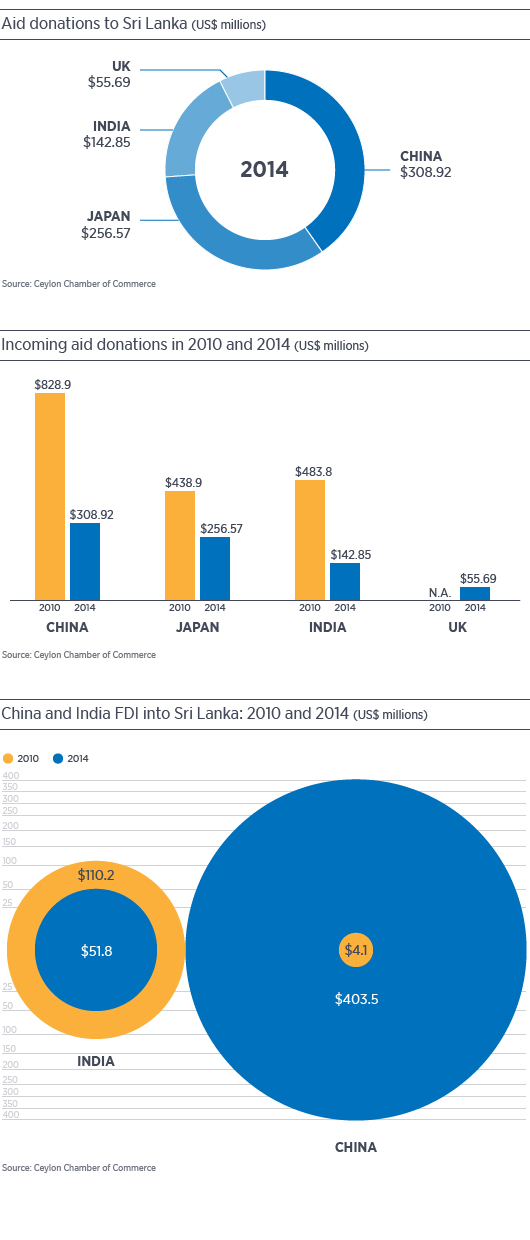

Now, with Asia’s economic rise, experts say Sri Lanka’s location has become even more alluring. Not only are three Asian powers – China, Japan and India – playing dominant roles in the global economy at the same time for the first time, there are also increasingly attractive markets and trade opportunities in Asia.

Now, with Asia’s economic rise, experts say Sri Lanka’s location has become even more alluring. Not only are three Asian powers – China, Japan and India – playing dominant roles in the global economy at the same time for the first time, there are also increasingly attractive markets and trade opportunities in Asia.

“Sri Lanka is the pivotal point for a global grand strategy,” R. Hariharan, a retired Indian army colonel and specialist in South Asian geopolitics, told CNBC. “Sri Lanka’s geography gives it an advantage disproportionate to its size.”

The small island nation with a population of 22 million has been rediscovering its strategic location for the past few years as it comes out of a 26-year civil war that depleted government resources and held back development. As Sri Lanka looks for assistance to reboot its economy, a largely two-way tussle for influence in the country and, in turn, the region is on.

China, India tussle

Sri Lanka also holds an attraction for both India and groups that would like access to India. Asia’s third largest economy is within “artillery range” of Sri Lanka, situated some 30 kilometers (19 miles) to the north of the island.

“We are at the doorstep of a dynamic market,” Anushka Wijesinha, chief economist at Ceylon Chamber of Commerce, said. “The Indian middle class market alone is set to be 10 times our entire population. Imagine the opportunities there.”

A tricky balancing act

“Sri Lanka needs to develop its economy using both Indian and Chinese help. We need both markets,” Shiran Fernando, lead economist at Frontier Research, told CNBC.

But China and India have not always been open to sharing influence, with both trying to leverage their “special relationship” with the island.

“The challenge is to find a balance between these two large countries and not take to one bloc,” said Nishan de Mel, executive director at Verite Research. “The pendulum is swinging but should end up in the middle.”

China’s early lead

In this vacuum, China landed contracts to build highways, ports and an airport in the south of the island, from a Sri Lankan government that was at the time open to Chinese expertise and money. India provided assistance in the war torn areas of the north, rebuilding homes and railway tracks, but China was by far the dominant partner.

Among the big-ticket Chinese projects was a port in Hambantota at Sri Lanka’s southern tip, built at a cost of around $360 million, with 85 percent funding from China’s Export-Import Bank. Another key project, a $1.4 billion port city in Colombo, was initiated by then-president Mahinda Rajapaksa’s government in 2014.

Funded by Chinese state-owned company, China Communications Construction, the port city project was due to be the single largest foreign investment in Sri Lanka – a multi-development project with a marina, malls, golf courses and even a Formula 1 track.

But development stalled amid controversy over the tender procedures and on concerns the project, to be built on reclaimed land, would damage the island’s beaches, and it was left in limbo when Rajapaksa’s government was voted out in early 2015, amid promises by the then-opposition, led by Maithripala Sirisena, to scrap the deal entirely.

The pendulum swings

With a new government, headed by President Sirisena, came a more pro-India stance. Sirisena visited India on his first overseas trip and Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi reciprocated within a month, using the trip to Sri Lanka to invoke the two countries’ cultural and religious links. He also promised India would develop an oil tank “farm,” offered $318 million in credit for rail works and a $1.5 billion currency swap between the central banks of the two nations, according to reports.

But within a year Sri Lanka was back wooing Chinese investments. The government has revived the port city, and followed up with a visit to China by Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe in April.

The trip was widely read as being aimed at mending relations as well as negotiating better terms on the port city for Sri Lanka, including a reduction in the $125 million penalty it received for previously suspending work on the mega-project.

Wickremesinghe also requested an equity swap on some of Sri Lanka’s $8 billion worth of Chinese loans.

“The government has done a U-turn on the port city project because reality set in,” the Chamber of Commerce’s Wijesinha told CNBC. “If we are to boost investment, we have to look at whoever brings in the investment and clearly China has the money.”

Some commentators maintain that Sri Lanka has cleverly managed its courtship with both India and China.

“At the end of the day, we don’t have a U.S. base on our shores, nor are the Chinese investments a de facto base and neither are we an annexure of India,” said a Colombo-based analyst, implying that the small island state had done well to maintain its sovereignty while balancing diplomatic and trade relations.

The next Singapore?

“We need to harness these investments, need major players to start using it. Strained relations with China also did not help,” said Frontier’s Fernando, adding that now that the prime minister had visited China, Chinese companies may start using the infrastructure they helped build.

Sri Lanka is also set to receive a $1.5 billion foreign reserve-boosting loan from the International Monetary Fund, which should help bolster investor confidence in the $80 billion economy, which already comes with the benefits of high levels of literacy and a vibrant democracy.

The loan is designed to help Sri Lanka avoid a balance-of-payments crisis as occurred at the end of the civil war in 2009 – a crisis that required a $2.6 billion IMF bailout. According to Reuters, Sri Lanka’s foreign reserves have fallen by a third from an October 2014 peak to $6.3 billion in January, mainly due to $1.3 billion in outflows from government bonds in 2015.

Sri Lanka has already taken one investment rating hit; Fitch Ratings downgraded the country’s long-term foreign and local currency issuer default ratings to B+ from BB-, citing increasing financing risks, significant debt maturities in 2016, the decline in forex reserves and weaker public finances as a result of low revenues.

The decisions made now are key, as Harsha de Silva, the country’s deputy minister of foreign affairs, told CNBC: “If we manage our policies right, we will become the next or even better Singapore or Dubai.”