A dossier

by Sachi Sri Kantha, February 21, 2021

Dr. Manorani Saravanamuttu

The dictionary defines a dossier as ‘set of documents, esp. record of information about a person or event.’ Here, I have compiled a brief dossier on Dr. Manorani Saravanamuttu, based on materials in my files and internet search. The prime reason being, as of now, there is no Wikipedia entry in English, for this courageous Tamil lady and mother of a talented young artiste from Sri Lanka. On the contrary, there are Wikipedia entries for Manorani’s son Richard de Zoysa and her divorced husband Lucien de Zoysa. Thus, this dossier collects materials predominantly on Manorani. Publicly, son Richard identified himself with his father’s name, and not with his mother’s Tamil maiden name.

Manorani (b. circa 1930) died twenty years ago, on Feb. 14, 2001. In 1990s, she was a household name among women activists in Sri Lanka. Her only son Richard de Zoysa (a 31 year old stage and Sinhala movie actor, writer and television news anchor) was abducted and killed by a death squad affiliated to the Sri Lankan government on Feb.18, 1990, then led by President Ranasinghe Premadasa (1924-1993) and Ranjan Wijeratne (1931-1991)

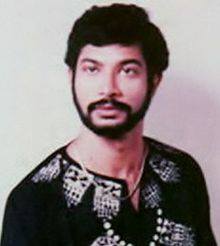

Richard de Zoysa (1958-1990)

Manorani, a family physician by professional training, was married to a Sinhalese Lucien de Zoysa (1917-1995), a notable cricketer, playwright, actor and radio personality. Richard was born on Mar 18, 1958. When Richard was 11, de Zoysa couple divorced and Manorani brought up her son as a single mother. Manorani was a courageous woman who valiantly took on the extra-judicial arm of the despots Premadasa and Wijeratne in early 1990s. According to Steven Coll’s 1991 report to the Washington Post (see below, Item 3), “members of Premadasa’s cabinet rose on the floor to denounce de Zoysa as a homosexual and a JVP sympathizer. ‘You keep referring to abduction and murder. What if it is not murder, but suicide or something else’” asked Ranil Wickeremesinghe, a government minister.”

In my view, Manorani was also gullible in advancing the political careers of SLFP’s phony human rights activists, current prime minister Mahinda Rajapaksa and Mangala Samaraweera. According to a 1995 Canada Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada report (Item 5), “Saravanamuttu was part of the leadership of the Southern-based Mothers’ Front when it was established, although the driving force behind the organisation was the Sri Lanka Freedom Party (SLFP)”. The same report also added: “Following the 1994 elections two leaders of the southern-based Mothers’ Front, MPs Mahinda Rajapakse and Mangala Samaraweera of the SLFP were re-elected and now serve in the cabinet of the government, Rajapakse as Minister of Labour and Samaraweera as Minister of Posts and Telecommunications.

According to the Amnesty International researcher, the Southern-based Mothers’ Front apparently has not determined what its role will be now that two of its leaders are members of the government. The new government has launched a commission of inquiry into the disappeared, although what role the Mother’s Front may play remains unclear.”

In the past 27 years, Mahinda Rajapaksa has shown his mettle. As is typical of a chameleonic politician, he stripped off his ‘human rights activist garb’ once he became a Cabinet minister

Items collected in this dossier include details of an audio interview to BBC World Service (1993) and a Youtube video (9 min), prepared by Nimal Ranjani and Paul-Marie Mendis, for the Centre for Family Services. In this interview, Manorani’s age is mentioned as 63.

An audio interview of 14 min. to BBC World Service in Feb.25, 1993, by Dr. Manorani Saravanamuttu. Program caption: Sparks from a Precious Stone.

https://www.bbc.co.uk/sounds/play/p033w956 [accessed Feb.21, 2021]

A Youtube video on Dr. Manorani Saravanamuttu

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nJ5WJUMkNq4 [accessed Feb.21, 2021]

Print materials are as follows:

Item 1: International Commission of Jurists report, Aug. 1990.

Item 2: Barbara Crossette – Killing stirs a land cowed by deaths. New York Times, March 31, 1990.

Item 3: Steve Coll – The mothers who won’t disappear. Washington Post, Mar 3, 1991.

Item 4: Human Rights Watch Report, for year 1990, on Sri Lankan Events.

Item 5: Canada Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada report, Feb.1, 1995.

Item 6: A tribute to Dr. Manorani Saravanamuttu, by Asian Human Rights Commission, Hong Kong, Feb.19, 2001.

Item 7: Kanya D’Almeida – Press Freedom & Enforced Disappearances: Two Sides of the Same Coin in Sri Lanka, Inter Press Service News Agency, Apr 30, 2018

*********************************

Item 1

A pdf file of Fact finding Commission report prepared by Anthony Heaton-Armstrong for International Commission of Jurists, Geneva, Aug. 1990 (28 pages)

Homicide of Richard de Zoysa fact finding mission report of Int Commission of Jurists Aug 1990

http://www.ipsnews.net/2018/04/press-freedom-enforced-disappearances-two-sides-coin-sri-lanka/ [accessed Feb.21, 2021]

**********************************

Item 2:

Colombo Journal; Killing Stirs a Land Cowed by Deaths

by Barbara Crossette [New York Times, Mar 31, 1990]

COLOMBO, Sri Lanka — The death squad came for her only child at 3:30 on a Sunday morning in February. Mother and son were torn apart in a few moments of confusion and blinding terror.

”One line from the Bible keeps going around in my head since then,” she said. ”Absalom. O, Absalom, my son!”

Colombo Journal; Killing Stirs a Land Cowed by Deaths by Barbara Crossette [New York Times, Mar 31, 1990]

But when the crowd gathered, and someone had covered the naked body with a sarong, people came closer and thought they recognized a distinctive face framed by a beard.

A Tougher Brand of Politics

The victim was Richard de Zoysa, one of Sri Lanka’s best-known television news anchors and a highly regarded 31-year-old actor and writer. He was preparing to leave Sri Lanka to become the Lisbon bureau chief of Inter Press Service, a Rome-based agency specializing in news from third-world nations.

For many Sri Lankans, the death of Mr. de Zoysa has become the catalyst for discussions about where this nation, South Asia’s most developed country, is heading under a new Government that seems to be overturning the traditions of an old, landed society led by a highly educated political elite, epitomized by J. R. Jayewardene, the former President.

A tougher brand of city politics is taking hold. Private security squads in armed convoys are changing the face of genteel Colombo.

The talk of the city was captured recently in one small cartoon on the front page of the independent newspaper The Island. In it, a man is reading a headline that promises an ”adequate supply of textiles for the new year.” He adds, ”But not enough to cover our moral nakedness.”

System of Abduction and Death

Mr. de Zoysa was a member of two local families, one Tamil, one Sinhala, both distinguished in politics, the arts, social service and medicine. His Tamil mother and Sinhalese father, now divorced, chose to raise him as an English-speaking Anglican. Since the age of 11, he had lived with his mother, Manorani Saravanamuttu, a physician.

Dr. Saravananuttu, making a great effort to control the emotions that now and then twisted her face as she talked about her son, is determined to force a full public accounting of his death, and to expose any efforts to concoct a cover-up.

The circumstances of his abduction and slaying, including reports from coastal villagers that indicate he may have been shot and dumped at sea by helicopter, point to official connivance if not inspiration and to a very well-organized system of abduction and death.

President Ranasinghe Premadasa not only came to Mr. de Zoysa’s funeral but also called Dr. Saravananuttu to his office twice to express his sympathy and vow to solve the case.

No Evidence of an Inquiry

But a month after Mr. de Zoysa’s death, his mother, who identified his body with certainty only by childhood scars, has not been able to obtain an official post-mortem report. The Government will not answer questions in Parliament about the case, saying it is before a magistrate’s court. The family lawyers can find no evidence of an investigation in progress.

”I am frightened for my country,” Dr. Saravananuttu said, speaking at a house where she is in hiding, fearing for her own life and that of a servant who might be able to identify some of the men who took Mr. de Zoysa away. One of them was in a police uniform. ”It’s not just Richard,” she said. ”As a doctor working in Colombo, I know of many others. There are many mothers, mothers without money, who come to claim lost sons and are not treated politely, who are sent away to live year after year in hope. I am the luckiest mother in Sri Lanka – I got my son’s body back.”

”I have learned that there is a grief beyond tears,” she said, adding that her first instinct was to have a private funeral. But then she decided that a large, extravagant display of mourning was needed to jolt the society into response.

Chill for the Intellectuals

”I want to bring a tear to every mother’s eye,” she said. ”I am angry. I am very angry. All I can do to fight for my son is to use his death for Sri Lanka.”

In a country all but benumbed by a year of horror marked by thousands of mutilated corpses killed by leftist rebels of the People’s Liberation Front or the semiofficial death squads that were formed to root them out, the death of Richard de Zoysa, one of Sri Lanka’s most popular citizens, provoked a long pent-up howl of anguish and fear.

”The cries of outrage and fury in the national newspapers suggest the therapeutic shock effect of Richard’s death,” wrote Mervyn de Silva, editor of the left-wing Lanka Guardian, a journal of political and social opinion to which Mr. de Zoysa occasionally contributed.

The killing of Mr. de Zoysa has sent a new chill through the intellectual middle class, because there was no obvious explanation why Mr. Zoysa might have been singled out for death, or by whom, though other television journalists were killed by the People’s Liberation Front before it was decimated by the arrests of its leaders last fall.

Departure Postponed for Exam

He held some views considered radical in this basically conservative society, had some friends who were homosexuals and had developed contacts for professional reasons with revolutionary groups, as many journalists here did. He was close to human-rights organizations and surrounded by theater people. He had friends everywhere.

Mr. de Zoysa was methodical, his mother said, and his last fatal decision was to postpone his departure from Sri Lanka to take a university examination that had been postponed several times.

”The saddest thing I found in his office,” Dr. Saravananuttu said, ”was that timetable and admission card to the exam.”

*****************************************

Item 3:

The Mothers who won’t Disappear

by Steve Coll [Washington Post, March 3, 1991]

COLOMBO, Sri Lanka — The letter arrived by regular post in the afternoon. A mailman carried it up the walkway of a posh bungalow lined with palms and splashed with tropical light. The letter was handwritten in English, addressed to Manorani Saravanamuttu, a medical doctor and a child of the island’s wealthy elite, perhaps the best known of the estimated 25,000 Sri Lankan mothers to lose a son to the death squads.

The letter went like this:

‘We condole with you regarding the death of your son Richard. He was a traitor to the cause of justice and prosperity to our motherland. Therefore he was removed …

You are about to set out on a venture seemingly to avenge your son’s death. If you do so, you too become a traitor …

MOURN the death of your son — as a mother you must do so. Any other steps will result in your death at the most unexpected time …

Only silence will protect you.’

Since the letter arrived last May, Manorani Saravanamuttu has considered at length the price of silence and the price of speech. When she decided to raise her voice, she says, it was less from heroism than anger, less from courage than desperation. She is alone — divorced, now childless. She felt she had nothing left to lose.

“They expect you to curl up in a corner and die of fear,” she whispers on a sultry Sunday morning, smoking, laughing and weeping through hours of conversation on her front porch. She is patrician by Sri Lankan measures — light skin, high cheeks, gray hair pulled back in a bun — and easily familiar with a Western stranger, confiding and intimate. She answers sometimes carefully, other times with emotion, stopping now and then to ponder aloud what the president of Sri Lanka will think if he reads this or that quoted from her lips.

“I had no one else to put into danger,” she says, explaining the origins of the journey that led her into exile and back in the months since the death threat arrived. “I kept going around to my friends saying, ‘They would do me a favor by killing me.’ They thought I had lost my head, but it was just my reaction. You can get crushed by grief, you can get crushed by fear, or you can just get angry.”

From Saravanamuttu’s anger the Mothers Front has risen, a mass movement of 25,000 registered mothers of Sri Lanka’s disappeared. Despite threats from the police and allegations of subversion from the government, the mothers held their first rally this month, timed to commemorate the abduction and execution of Richard de Zoysa, Saravanamuttu’s only son, a journalist, actor and human rights activist.

Where it all will lead is difficult to predict on an island so entangled in violence, ethnic hatred and civil war. Perhaps quixotically, Saravanamuttu hopes the mothers will forge the beginning of a peaceful reconciliation and change their country forever.

“It is my belief that men don’t feel sorrow the way that women feel,” she says. “I realized that what Sri Lanka needs is a peaceful force. The women are saying, ‘We are going mad with grief at home alone.’ Now at least we are doing something.”

The Paradox of Horror Perhaps you have heard about the death squads in Sri Lanka, or the headless corpses that smolder in the mornings on the roadside, or the eight years of civil war, or the ethnic hatred so fierce it causes literate, educated men to set each other on fire. Perhaps you have also heard about the white beaches, or the crystal ocean water running over coral reefs, or the lush tea estates, or the thousands of elephants, or the first-class hotels and casinos, or the Sri Lankan people — impoverished but almost universally literate, gentle and welcoming.

There is no easy way to explain Sri Lanka’s death squads. For one thing, this is not a set piece where Evil stands to one side and Good to the other, locked in moral confrontation. But it is helpful to sort it all out, if only better to understand the courage and despair of Manorani Saravanamuttu and the other mothers of the disappeared.

One place to begin is with the departure of the British from Ceylon, as Sri Lanka was once known, following World War II. In Colombo, as in many other capitals of the empire, the British left behind what amounted to an entourage — a tiny, English-speaking elite of Sri Lankan lawyers, doctors, army officers, administrators and clerks who had managed the island’s affairs for more than a century.

Many trees have fallen and many books have been written in an effort to explain what went wrong between 1948 and 1983, when the civil war in independent Sri Lanka began. Some blame the British for sowing the seeds of injustice. Some blame the Colombo elite for jealously guarding its privileges. Some blame a new generation of nationalist politicians who exploited ethnicity and religion to win votes.

The island split in two, with the Hindu, ethnic Tamil minority in the northeast fighting for a homeland independent from the Buddhist, ethnic Sinhalese majority in the south. Tamil guerrilla groups formed in the north and took to the jungle to battle the government’s Sinhalese army.

The war grew bloodier and bloodier until 1987 when India, which sympathized with the Hindu Tamils, dropped in with 100,000 soldiers, ostensibly to restore peace and protect the Tamils from the Sinhalese. The arrival of Indian troops provoked a backlash in the south, where the Sinhalese live.

Sinhalese radicals, mainly from the oppressed lower castes, formed the People’s Liberation Front, known by its Sinhalese initials JVP, a Maoist, Buddhist, totalitarian revolutionary group whose goals and methods have been compared to those of Pol Pot’s Khmer Rouge in Cambodia. Beginning in 1988, the JVP dedicated itself to overthrowing the Sri Lankan government by violence and expelling Indian troops from the island.

The JVP resorted to extreme forms of terrorism. One of its favorite tactics was to enter the home of a government policeman while he was out on duty, slaughter his wife and children with guns and knives, then leave the bodies for him to find when he came home from work.

With the island on the verge of chaos and collapse, the government decided to fight fire with fire. According to Sri Lankan politicians, security force officers and international human rights groups, the government deliberately recruited policemen who had lost their wives and children in bloody JVP attacks, sent them into JVP areas, and told them to do whatever was necessary to defeat the enemy.

In that way, in 1988, the death squads were born.

The Abductions To travel in Sri Lanka’s death squad country in 1989 and 1990 was to tour a strange landscape of slaughter and silence.

During that time, at least 25,000 and perhaps as many as 60,000 (the estimate of European parliamentarians), Sinhalese boys and men — identified by the government as JVP suspects — disappeared from their homes. They were abducted at night by squads of armed men in civilian dress who drove around in green Mitsubishi Pajero jeeps. By 1990 the squads were so bold that they operated in daylight, and a foreigner could stand by the side of the road and watch the men from the jeeps barge into a village home, pull out a frightened teenager and drive away with him.

In the mornings, piles of corpses appeared on beaches, floating in muddy rivers or burning along roads. Crowds of villagers gathered and stared mutely.

They confided that if you were from certain castes or villages associated with the JVP, it was a virtual certainty that you would be killed by a death squad if one ever found you.

One of the strange things was that the tourists kept coming — Italians, Germans and East Europeans drawn by pristine sands and budget prices. They went jogging when the sun came up, literally hopping over the bodies of the dead. Both the JVP and the government declared foreigners off limits in their war, to encourage the uninterrupted flow of vital foreign exchange.

In those days, many in Sri Lanka and abroad seemed to view the death squads as a tolerable evil necessary to defeat the greater evil of the JVP. Mothers and wives of those who disappeared sobbed with grief and declared to visiting journalists the innocence of their relatives. Human rights groups documented the disappearances and counted the burning corpses. But Western countries put little pressure on Sri Lankan President Ranasinghe Premadasa, who said he did not control the death squads directly and that, in any event, he was trying to save his country from an apocalyptic revolution.

In November 1989, the government announced the capture and death of the JVP leader, Rohana Wijeweera. A spokesman said Wijeweera was shot while attempting to escape from security forces. The war against the JVP had been won, the spokesman claimed. Many Sri Lankans celebrated.

But that winter, in the south, the death squads roamed unrelentingly. Thousands more disappeared. Corpses continued to appear. Opposition politicians, who had generally supported the anti-JVP campaign, began to question whether Premadasa intended to use the death squads to consolidate his hold on power.

Some asked how it was, exactly, that a government was supposed to instruct a death squad that its work was finished, that the enemy was defeated? Did you send a memo? Award a certificate of meritorious service and a pension? What did you do with these men, so angry and accustomed to brutality?

Neelan Tiruchelvan, a Colombo attorney, said that winter that he feared that Sri Lanka had become a country that had “lost its ability to distinguish between right and wrong.”

“The frightening thing is that when this violence is unleashed, you don’t quite know where it will end,” said Mangala Samaraweera, who has helped organize the Mothers Front. “I don’t really know how one could stop it. They {the government} are moving to a situation where they are getting more systematic and dictatorial.”

It was amid such questioning, one year ago in February, that Richard de Zoysa was murdered and the mothers of the disappeared began to find their voices.

The Disappearance of Richard de Zoysa Richard de Zoysa and his mother “both lived extremely busy professional lives — we were two buddies sharing the same house, rather than parent and child,” Manorani Saravanamuttu recalls. After the divorce, when Richard was about 13, she devoted herself to a general medical practice at hospitals and clinics. Patients often drove to the gates of their bungalow in a wealthy Colombo neighborhood, seeking attention in the middle of the night.

Richard’s was a household face in Sri Lanka. For a while, he anchored an evening news broadcast on state-owned television. An actor, he played a prominent role in a popular TV series called “Neighbors,” a light satire on the pretensions of Colombo’s upwardly mobile middle classes. In journalism, he began to work with the International Press Service, a European agency specializing in the Third World.

Some believe that it was de Zoysa’s work for IPS, documenting death squad killings in the south, that led to the events of Feb. 18, 1990. Others say he was killed because he helped write a play that made fun of Premadasa.

The play was called “Who Is This? And What Is He Doing?” which happened to be the campaign slogan on which Premadasa ran in the national elections of 1988. Written by hand in the Sinhala language, the play depicts a lunatic asylum in which many of the doctors and patients are recognizable politicians from Premadasa’s United National Party, and the new chief of the asylum is Premadasa himself.

“It’s not a very readable play,” says Batty Weerakoon, Saravanamuttu’s lawyer, who has seen one of the few copies. “It was something on which was hung so many bits of jokes by way of poking fun at government personalities and primarily at the president and his family.” Weerakoon, like some others, doubts that de Zoysa was closely involved in writing the script, which does not bear the name of any author. Others say de Zoysa helped organize the theatrical troupe that was to perform the play and contributed to the writing.

Sri Lankans have been unable to judge the play’s merits, since on the night before its debut at a Colombo theater during that winter of 1989-90, its producer, Luxman Perera, disappeared without a trace. His body has never been found. The actors and audience, unnerved by this development, declined to go forward.

In any event, it was six weeks after Perera’s disappearance that a death squad arrived at the de Zoysa home one morning two hours before dawn.

“People ask, Why did I even come to the door?” Saravanamuttu says as if a stranger might believe this was all her fault. “But I was on a paging system and sometimes relatives and patients came to the house in the middle of the night {for medicines}. Even the domestic {servant} thought it was a patient.”

It was over in 15 minutes. Armed men barged through the front door, climbed the stairs, pulled de Zoysa from his bed, walked him outside and put him into a waiting jeep. “I ran down and up to the jeep,” Saravanamuttu remembers. “I went to the front seat. ‘Where are you taking my son?’ There was no answer; they drove off at high speed.”

The following morning, de Zoysa’s body washed ashore on a beach near Colombo. He had been shot through the head at close range. Fishermen recognized him as a television actor.

In the swirl of grief and rage that followed, Saravanamuttu says, she had no clear idea what she would do. She says the movement of mothers she has created arose spontaneously from her throat in words she had not planned to speak. She remembers it exactly: She had just come out of the inquest, which established that her son had lived for perhaps 45 minutes after his abduction. She was angry and disoriented. Reporters surrounded her, seeking a comment.

“I am the luckiest mother in Sri Lanka,” she told them as she climbed into her car. “I got my son’s body back. There are thousands of mothers who never get their children’s bodies back.”

With those words, the silence of Sri Lanka’s mothers ended, and a movement began.

What Can They Hope For? Premadasa himself came to the funeral at de Zoysa’s home. Saravanamuttu was too overcome with grief and anger to speak with him, but the president conveyed his condolences nonetheless. Saravanamuttu steadfastly refuses to speak about her relationship with Sri Lanka’s president — it is too sensitive, she says. But others close to the family say Premadasa has been oddly sensitive and solicitous since de Zoysa’s body washed up on the beach.

One difference between Richard de Zoysa and the thousands of Sri Lankan youths who died before him cuts to the heart of politics and power on the island: De Zoysa was born to a high caste, spoke English fluently, went to the right schools and lived in a good neighborhood.

These facts may have tempered the Sri Lankan government’s response to Manorani Saravanamuttu’s campaign on behalf of the mothers of the disappeared, but they have not prevented it from opposing her quest, at virtually every stage, for answers about her son’s murder.

When Saravanamuttu pressed a court case against police officers she identified as the men who took her son away, the attorney general intervened and said there was no evidence to proceed. After the death threat arrived last May, she went abroad to Canada, New York and England. This winter, she decided it was time to come home because “this is my country. I am not against my country. I was only seeking justice.”

The government remains as hostile as before. In February of this year, when opposition members of Parliament sought an independent commission of inquiry into the case, members of Premadasa’s cabinet rose on the floor to denounce de Zoysa as a homosexual and a JVP sympathizer.

“You keep referring to abduction and murder. What if it is not murder, but suicide or something else?” asked Ranil Wickeremesinghe, a government minister.

“The more you try to stifle this inquiry, the more people think you are responsible for this murder,” answered opposition member C.V. Gooneratne.

The motion for a commission of inquiry was defeated, with all of Premadasa’s party members voting against. One parliamentarian, Prince Casinader, lamented that he would now have nothing to tell the hundreds of mothers who had written him recently to ask what happened to their sons. “All those mothers are not Mrs. Saravanamuttus, who can go and file habeas corpus cases. They trek through the night and believe their loved ones are somewhere, six feet underground,” he said.

Leaders of the Mothers Front say they are apolitical and seek not a change of government but only a modicum of compensation for what they have suffered. Disappearances mean that mothers and widows cannot obtain death certificates necessary to collect insurance benefits and property. Among other things, the Mothers Front seeks a one-time payment to the relatives of the dead and missing.

Though she has decided to lead thousands of Sri Lankan mothers into the street, Saravanamuttu is skeptical that her campaign will accomplish anything. “There does seem to be no hope for the country,” she says. “But one cannot think in those terms. At some stage, there has to be a solution.”

In the meantime, she is driven less by a vision of the future than by a need to reconcile the past. “What I hate these people for is their lies,” she says slowly and softly as the noon sun rises over her front garden. “They tell their lies, and we never have a chance to tell the truth.”

***********************************************************

Item 4:

Human Rights Watch Report, for year 1990, on Sri Lankan Events

[https://www.refworld.org/docid/467fca3710.html; accessed Feb.21, 2021]

Relevant paragraphs on Dr. Manorani Saravanamuttu, are presented below.

“In what has become one of the most publicized cases of death squad activity in Sri Lanka in 1990, Richard De Zoysa, a respected actor and journalist who had been outspoken in his criticism of human rights violations by the Sri Lankan security forces, was found murdered on February 19. Eyewitnesses reported that on the morning of February 18, six gunmen, two wearing police uniforms, arrived in a police jeep and took De Zoysa from his home. Other witnesses reported that they knew some of the abductors to be members of a special police team that reported directly to President Ranasinghe Premadasa.

De Zoysa’s mother, Dr. Manorani Saravanamuttu, positively identified Senior Superintendent of Police Ronnie Gunasinghe as the leader of the group of abductors. In statements to the police and, through her lawyer, to the court of inquiry, she also said that she had information implicating a second police officer, Ranchagoda, in the abduction. She has continued to press for a full inquiry into her son’s death, despite death threats received in May warning her away from the case. Her lawyer, Batty Weerakoon, received a similar threat, as did two police guards appointed for his protection.

Not unexpectedly, a court-ordered investigation by the police into the charges against their colleagues made little headway. At a hearing before the court on August 30, representatives of Attorney General Sunil De Silva reported that there was insufficient evidence against Gunasinghe to proceed against him. Gunasinghe remains on active duty.

Attempts to press for an independent inquiry into the De Zoysa abduction and murder have so far been unsuccessful. The police officers identified by Dr. Saravanamuttu have brought a defamation suit against her.”

**********************************************

Item 5:

Sri Lanka: Information on the group Mothers’ Front and how members are treated by the authorities

[Canada Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada, Feb.1, 1995]

https://www.refworld.org/docid/3ae6ab4d68.html accessed Feb.21, accessed on Feb.21, 2021

“According to information faxed to the DIRB by INFORM, a Sri Lankan human rights organisation, three groups are known to have used the name Mothers’ Front in Sri Lanka (16 Feb. 1995). INFORM reports that in the early 1990s a Mothers’ Front group supported by the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) existed briefly in the Eastern Province, but that no other information is available on this group. A subsequent fax received by the DIRB from INFORM reports that a Mothers’ Front has been operating in southern Sri Lanka since July 1990, while another Mothers’ Front began work in northern Sri Lanka in August 1984 (17 Feb. 1995). For information on the treatment of members of the northern and southern Mothers’ Fronts, and on the current status of the two groups, please consult the attachments.

The Sri Lanka Monitor contains a report on the second annual convention of the Mothers’ Front, which took place in Colombo on 23 June 1992, but does not identify which Mothers’ Front group held this event (June 1992, 4). However, this newsletter reports that 3 000 “grieving relatives of the disappeared heard prominent Sri Lankan women such as Badulla SLFP MP Hema Ratnayake … and Dr. Manorani Saravanamuttu …”. The newsletter also reports that this Mothers’ Front group wants an independent commission to investigate all disappearances since 1988″ (ibid).

In a telephone interview, a researcher with Amnesty International in London corroborated the existence of a southern-based Mothers’ Front group (16 Feb. 1995). According to the researcher, Saravanamuttu was part of the leadership of the southern-based Mothers’ Front when it was established, although the driving force behind the organisation was the Sri Lanka Freedom Party (SLFP). The Amnesty International researcher added that this Mothers’ Front group worked in the southern provinces of Sri Lanka to publicise the issue of disappearances, and to demand an investigation into killings and disappearances committed by state authorities. The reasearcher was unable to corroborate the existence of the other two Mothers’ Front groups .

In a subsequent telephone interview, the Amnesty International researcher stated that authorities had disrupted or interfered with demonstrations organized by the Mothers’ Front (17 Feb. 1995). The researcher could not substantiate reports of ill-treatment of members of the Mothers’ Front. Information on the treatment of members in villages, or what response their participation in Mothers’ Front activities would receive from the police is difficult to find, according to the researcher, although the activities of Mothers’ Front participants were public and would be known by the police.

According to the Amnesty International researcher, the Mothers’ Front relied on a network of supporters in the villages to conduct rallies, marches and other ‘high profile public demonstrations’ in order to pressure the government into investigating and prosecuting those responsible for the disappearances and killings committed during a counter-insurgency campaign against the People’s Liberation Front (Janatha Vimukhti Peramuna or JVP) (16 Feb. 1995.). Following the 1994 elections two leaders of the southern-based Mothers’ Front, MPs Mahinda Rajapakse and Managala Samaraweera of the SLFP were re-elected and now serve in the cabinet of the government, Rajapakse as Minister of Labour and Samaraweera as Minister of Posts and Telecommunications (The Sri Lanka Monitor Aug. 1994, 2).

According to the Amnesty International researcher, the southern-based Mothers’ Front apparently has not determined what its role will be now that two of its leaders are members of the government. The new government has launched a commission of inquiry into the disappeared, although what role the Mother’s Front may play remains unclear.”

****************************

Item 6:

Dying without Redress: A Tribute to Manorani Saravanamuttu (Sri Lanka), a mother who fought for justice

Asian Human Rights Commission, Hong kong, Feb.19, 2001

[accessed Feb. 21, 2021]

“Manorani Saravanamuttu, who was more popularly known as Richard De Soyza’s mother, passed away on 14th February 2001. Richard was a popular figure in Colombo, Sri Lanka a young journalist, film and dramatic actor who was kidnapped by government security personnel. His body was later found by the seashore and identified by Manorani.

Richard was killed on the night of February 17th/18th 1990. The speculation is that his dead body was dropped from a helicopter flying at a certain height with the expectation that the body would sink to the bottom of the sea and never be found. Manorani identified one of the kidnappers as one Ronnie Gunasinha by seeing his picture on a TV broadcast. Gunasinha was a senior security officer of the late president Premadasa. He was among those who died in the explosion that killed the President on 1st of May 1993. (Though some saw this as divine justice, Manorani was much more humane, and even showed sympathy for Gunasinha’s children. A commentator who has spoken to her mentioned she preferred justice meted out in a court of law, which would have helped people achieve genuine reconciliation.)

Richard De Soyza’s killing was part of huge number of disappearances which took place between 1988 and 1991, the number of which is estimated by the state as around 30,000 and by the civil society organizations as 60,000. Manorani will be remembered as one who symbolized the mothers of the disappeared who rallied to demand justice. She saw her son’s death as part of a wider phenomenon: the collapse of the Sri Lankan society, rule of law and morality. Though by family and by profession she was a medical doctor belonging to the elite of the country, as a mother Manorani transcended the class barrier at the moment she lost a son. During the last 11 years of her life she played a very strong part in raising fundamental issues regarding the Sri Lankan society which will remain valid until these problems are finally resolved. In the days of intense terror she courageously and fearlessly worked throughout the country, in solidarity with tens of thousands of mothers who lost children in similar circumstances to her. She became a powerful spokesperson. The following are her words: ” Whether they know why they are doing it, I do not know. Whether they have been told today is the night for so and so. They probably do not question why we are doing this. What has this fellow done to us that we should go and take him, and kill him. That I do not know. But they come. They come with their eyes that are empty of everything. They come with their guns. They come with their assurance that they will not fail in their missions.

They come and knock at doors. Ring bells and they look at you, and frighten you, and threaten you….. If I had thought for one moment that they had come to take my son I would have died there at the door…..It’s the women who bear the brunt, and its the women who are the strong ones, because, when you lose a child you lose yourself ” (quoted from a video interview by Nimal Mendis)

“It is the most devastating experience to have a child pulled out of your arms. My boy ‘disappeared’ and 48 hours later his mutilated body was found. Since then I have received numerous threats, anonymous letters, telephone terror and I am also certain that my telephone is tapped. I want to pursue my son’s case. Many friends and colleagues have asked me to stop: “the one who seeks the battle should not complain about the wounds”. But I know there are tens of thousands of relatives who have been affected by the violence. I will never advise the women I work with to forget, I will tell them that they must speak. 20.000-30.000 did not join, out of fear of reprisals to other relatives”. (quoted from Linking Solidarity).

She was persistent in her call for justice. In this she was bitterly betrayed. Even those who made use of the anger and bitterness of the mothers whose children disappeared for electoral purpose betrayed their call for justice. Sri Lanka remains one of those countries where the justice system is too weak to provide a response to such calls for justice.

It is unable even to respond to the extent of Chile or Argentina. This not just a weakness of the justice system but of the society as a whole. Sri Lankan society remains in a primitive state, unable to deal with the fundamental forms of in injustice entrenched in it. It is only the mothers facing such problems who can make the best critique of society, morality and justice systems. The best way to honour them is to face the questions that turn their lives into tragedies. To not do so is to dishonour them as a society and as individuals in the society.

Let us remember Manorani by committing ourselves to work towards the reform of society, morality and the Justice system (comprised of Police, Prosecutions and Judiciary) that have betrayed Manorani and thousands of other like her.”

**********************************************

Item 7:

Press Freedom & Enforced Disappearances: Two Sides of the Same Coin in Sri Lanka

by Kanya D’Almeida– Inter Press Service News Agency, Apr 30, 2018.

http://www.ipsnews.net/2018/04/press-freedom-enforced-disappearances-two-sides-coin-sri-lanka/ [accessed Feb.21, 2021]

NEW YORK, Apr 30 2018 (IPS) – When Sri Lankan journalist Richard de Zoysa was abducted from his home in Colombo on the night of February 18th, 1990, his family knew there would be dark days ahead. The population was still reeling from one of the bloodiest episodes in the island nation’s history – a government counterinsurgency campaign to crush a Marxist rebellion in southern Sri Lanka, which left between 30,000 and 60,000 people dead at the hands of government death squads.

Even more disturbing than the extrajudicial killings was the wave of enforced disappearances that took place between 1988 and 1990: tens of thousands of Sinhalese men and boys suspected of being members or sympathizers of the People’s Liberation Front, or JVP, went missing, never to return.

At the time of his kidnapping, de Zoysa was a stringer for this publication, filing regular reports on the political violence plaguing the country. He was on the verge of accepting the post of Bureau Chief of the agency’s Lisbon-based European desk when the goons came knocking.

For hours that bled into days, his mother, Manorani Saravanamuttu had no idea what had become of him. High-ranking officials assured her that he was alive, in police custody, but refused to give her exact coordinates when she asked to be allowed to bring him some clothing – he had been wearing only a sarong when he was kidnapped – or a meal.

It later transpired that while she was making frantic phone calls and searching for answers, de Zoysa was already dead, shot in the head at point blank range, and his body dumped in the Indian Ocean, a tactic that had become a common feature of the government’s systematic abductions.

A fisherman happened to recognize his face – de Zoysa was also a well-known television personality at the time – when his body washed up on shore in a coastal town just south of the capital. He alerted the authorities who in turn contacted de Zoysa’s mother.

According to a 1991 Washington Post interview with Saravanamuttu, the discovery of her son’s body was a turning point, for her personally, and for the nation as a whole. When she walked out of the inquest a few days after de Zoysa’s abduction, she found herself surrounded by reporters, to whom she made a statement that resonated with countless families across the island: “I am the luckiest mother in Sri Lanka. I got my son’s body back. There are thousands of mothers who never get their children’s bodies back.”

Mothers of the Disappeared

Saravanamuttu’s statement quickly catalyzed a movement known as the Mother’s Front, which had been a long time coming. Perhaps due to her privileged status as a member of the country’s English-speaking elite, she became a kind of totem pole around which women from the poorer, politically marginalized and largely Sinhala-speaking rural belt could gather, and from which they could draw strength. By 1991, according to the Post, the Mother’s Front counted 25,000 registered members.

The movement did not succeed in bringing justice to many of its victims. To this day, not a single person has been convicted for de Zoysa’s murder. Ministers who opposed Saravanamuttu and others’ attempts to seek answers in the murders or disappearances of their loved ones continue to hold positions of power within the government – Ranil Wickremesinghe, who the Post quoted as brushing de Zoysa’s murder off as “suicide or something else”, now serves as the Prime Minister, the second-highest political office in the country.

Amnesty International estimates that since the 1980s, there have been as many as 100,000 enforced disappearances in Sri Lanka.

The Mother’s Front movement did, however, make a crucial contribution to the country’s political landscape, one which continues to have ramifications today: it tied together forever the plight of Sri Lanka’s disappeared with the fate of its journalists and press freedom – or the lack thereof.

Exactly 20 years after de Zoysa was assassinated, another journalist’s disappearance prompted a woman to step into the global spotlight, much as Saravanamuttu did back in the 90s. This journalist’s name is Prageeth Eknaligoda, and he was last seen on January 24th, 2010. He telephoned his wife, Sandhya around 10 p.m. to inform her that he was on his way home from the offices of Lanka eNews (LEN), where he was a renowned columnist and cartoonist. He never arrived.

From local police stations all the way to the United Nations in Geneva, Sandhya has searched for answers as to his whereabouts. It is only in the last two years that some information regarding his abduction and detention by army intelligence personnel has been revealed.

Both Saravanamuttu and Sandhya Eknaligoda have received international recognition for their tireless campaigning. In 1990 de Zoysa’s mother accepted IPS’ press freedom award at the United Nations on her son’s behalf, and last year Sandhya was honored with a 2017 International Woman of Courage Award. But back in Sri Lanka, she faces a government and a public that is at best indifferent, and at worst openly hostile to her continued efforts to find her husband.

A New Front: Tamil Women in the North

Sandhya has also been one of the few women, and one of the lone voices, connecting the issue of press freedom with the movement of families of the disappeared led by Tamil women in Sri Lanka’s northern province, where the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) waged a 28-year-long guerilla war against the Government of Sri Lanka for an independent homeland for the country’s Tamil minority.

Since January 2017, hundreds of Tamil civilians have observed continuous, 24-hour roadside protests in five key locations throughout the former warzone – Kilinochchi, Mullaithivu, Trincomalee, Vavuniya and Maruthankerny (Jaffna district) – demanding answers about their disappeared loved ones.

Like the Mother’s Front in the 1990s, this movement too has been several years in the making. When the civil war ended in 2009, some 300,000 Tamil civilians were rounded up and detained in open-air camps, while hundreds of others – particularly men who surrendered to the armed forces – were taken into government custody under suspicion of being members or supporters of the LTTE.

But while the camps have closed and a large number of people reunited with their families, an estimated 20,000 people are still unaccounted for, including those who disappeared in the early years of the conflict, as well as others who have been abducted as recently as 2016 and 2017.

In 2016, Parliament passed a bill to establish an Office of Missing Persons (OMP) tasked with investigating what Foreign Minister Mangala Samaraweera called “one of the largest caseloads of missing persons in the world.”

However, rights groups like Amnesty International raised concerns about the bill, including the government’s failure to consult affected families throughout the process. This past March, the government passed a bill that would, for the first time in the country’s history, criminalize enforced disappearances.

But these cosmetic measures have failed to yield concrete results.

In an interview with IPS, Ruki Fernando, a Colombo-based activist who has been visiting the protests in the northern province, noted that Tamil families’ decision to spend day after day in the burning sun by the side of polluted, dusty highways and roads is indicative of their lack of faith in government mechanisms like the OMP and the judiciary to bring them relief. He also called attention to the dismal levels of support or solidarity they have received from Sri Lanka’s broader civil society, including from English and Sinhala-language media or women’s groups in the capital.

“It’s not fair that these families – particularly elderly Tamil women who are leading the protests – should have to carry this burden alone. They have already suffered heavily during the war – they starved in bunkers, they didn’t have medication for their injuries, they have lost family members. All these factors have made them physically weak and emotionally vulnerable, yet now they are also shouldering the burden of keeping these protests going.”

He recalls meeting women as old as 70, adding that protestors sometimes don’t have food, and must endure the vagaries of the weather in the arid Northern province. Some of the younger women are forced to bring their children with them. And most, if not all of these families, face the additional financial hardship of having lost their primary breadwinner, or losing out on livelihoods in order to participate in the protests for long periods.

“In my memory, such a strong movement led by women, occurring simultaneously in five locations across the North and East, or any region, is unprecedented,” Fernando said. “And yet it has not become a priority for the rest of the country.”

He called Sandhya Eknaligoda’s participation in the protests as a Sinhala Buddhist ally an “exception” to the rule of general indifference, which he chalked up to a combination of political and ideological issues.

“Some people believe these protests are too radical, too politicized, that there should be more cooperation with, and less criticism of, the government,” he explained. But as Fernando himself noted in an article for Groundviews, one of Sri Lanka’s leading citizen journalism websites, Tamil families have met repeatedly with elected officials, including President Maithripala Sirisena, to no avail.

No Closure

Fernando is not the only one to draw attention to Tamil families’ disadvantaged position with regard to both deaths and disappearances.

Another person to make this connection was Lal Wickrematunge, the brother of journalist Lasantha Wickrematunge, former editor-in-chief of the Sunday Leader who was murdered in broad daylight in 2010, and whose killers still haven’t been brought to justice.

Lal pointed to the ongoing investigation by the Criminal Investigation Department into military intelligence officers’ involvement in the kidnapping and torture of former deputy editor of The Nation newspaper, Keith Noyahr – and the arrest earlier this month of Major General Amal Karunasekera in connection with multiple attacks on journalists, including Noyahr, and Lasantha Wickrematunge – as a possible avenue of closure for the families.

According to a recent report in the Sunday Observer, “The assault on former Rivira Editor Upali Tennakoon and the abduction of journalist and activist Poddala Jayantha are also linked to the same shadowy military intelligence networks, run at the time by the country’s powerful former Defence Secretary, Gotabaya Rajapaksa.”

But Lal Wickrematunge told IPS in a phone interview that while his family, along with international rights groups, are “keenly watching the progress of the investigation, which will determine if the government is serious about law and order”, he is concerned about those who may never receive answers – such as the families of two Tamil journalists who were assassinated in 2006.

Suresh Kumar and Ranjith Kumar were both employees of the Jaffna-based Tamil-language daily Uthayan, whose employees and offices have been attacked multiple times, according to the Committee to Protect Journalists.

Other disappeared Tamil journalists whose cases receive scant attention include Subramanium Ramachandran, who was last seen at an army checkpoint in Jaffna in 2007.

For Fernando, the task of keeping the torch lit for Sri Lanka’s dead and disappeared cannot be laid at the feet of their family members alone – it is a responsibility that the entire country must share.

“What we need first and foremost are independent institutions capable of meting out truth and justice and winning the confidence of the families. And secondly, there is a need for stronger support for victims’ families from civil society – activists and professionals like lawyers, journalists and women’s groups.”

“Pushing for answers about what happened, and demanding prosecutions and convictions requires an exceptional degree of commitment,” he added. “Not everyone has the strength to wage such a battle, on a daily basis, against extremely heavy odds.”

******