‘Tamil Guardian’ editorial, London, January 9, 2017

Three years after the election victory of Maithripala Sirisena and Ranil Wickremesinghe’s ‘unity government’, the failure of meaningful progress on key issues must be confronted head on if visions for accountability, justice and lasting peace are ever to be achieved. While the government has succeeded in opening up sufficient space to garner international praise, with political space in the South having certainly fared well under the present regime, it has abjectly failed to deliver on commitments made to the Tamil people. As the wave of protests which defined the ‘good-governance’ regime’s third year in power illustrate, there is rising frustration among Tamils on the lack of progress on issues dubbed as easily deliverable – demilitarisation, land release, repealing the Prevention of Terrorism Act and releasing or charging political prisoners.

Key to international support for the Sirisena-Wickremesinghe alliance was Sri Lanka’s promise to implement the 2015 UN Human Rights Council co-sponsored resolution which called for a hybrid mechanism to be established to ensure accountability for mass atrocities committed at the end of the armed conflict in 2009. Yet almost three years on, the government has failed to produce a tangible plan of implementation. Failing to take any step towards beginning an honest conversation within the South on the need for accountability for reconciliation, it instead proceeded to reassure its Sinhala electorate that no Sri Lankan soldier will face a war crimes tribunal.

Indeed, nothing exemplifies more the pervasiveness of impunity on the island and the lack of political will to address accountability for Tamils, than Associated Press reports of ongoing torture and rape of Tamils by security forces as recently as 2017. Several international human rights experts from the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, to Special Rapporteurs and international NGOs have expressed serious concern about these recent allegations as well as about Sri Lanka’s pronounced unwillingness to either investigate the crimes of the past or kick-start any meaningful process of transitional justice. The UN human rights chief has even called for the exercising of universal jurisdiction to counter “the absence of credible action in Sri Lanka”.

For victims and their communities who have tried and failed to achieve justice through the domestic courts, who have engaged repeatedly with successive government led commissions, the platitude that they should have faith in this government is grating. The past year saw almost weekly commemorations in the North-East of state-sponsored assassinations and massacres that span decades, all underscored by the same slogan: still no justice. Families of the disappeared continue to chalk up the tally of days they have been protesting on the roadside, well into the 300s, yet no answers are forthcoming. These families have stated unequivocally that they do not expect the Office for Missing Persons to provide the answers they are looking for.

As has been demonstrated throughout the last three years, praise without pressure and unwavering engagement without scrutiny has not delivered the desired reforms. Promises to repeal the PTA, which gained traction while Sri Lanka’s suitability for trade concessions was being assessed by the European Union, now lay by the wayside several months after the concession was granted. Military-to-military engagement has allowed Sri Lankan leaders to declare that their armed forces have regained international prestige – proclamations that both undermine the drive for accountability and normalise the very militarisation which the Tamil community is struggling to break free of. Promises of a new constitution that would pave the way for a meaningful political solution for Tamils have been replaced by promises to the Buddhist clergy that no power will be ceded.

Three years on, the unity government’s excuses for its lack of progress on transitional justice and accountability and urgent reforms including demilitarisation, land release and repealing the PTA, and its call for more time and more expertise, can no longer be considered tenable. This government – a coalition of Sri Lanka’s two main parties, with the unwavering support of the main Tamil party and the international community could not have been in a more advantageous position. Yet in line with its predecessors, the unity government chose not to make the difficult steps towards confronting the state structures which perpetuate Tamil oppression, but instead to pander to Sinhala majoritarianism. As the government enters its fourth year in power, it is clear the international community’s current approach of seemingly unconditional support is not effecting change. The past three years are but a continuum in the Sri Lankan state’s Sinhala ethnocracy which has consistently proved itself unwilling to deliver justice or meaningful political power to the Tamils by and of itself. Only through international pressure and critical engagement will any meaningful progress be seen.

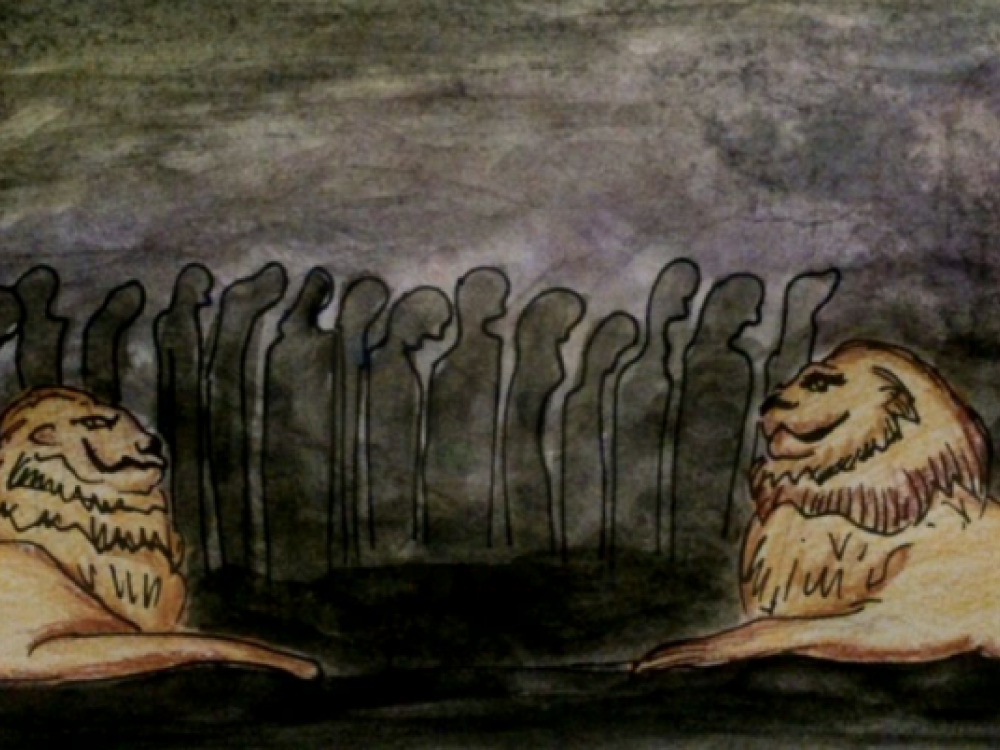

Illustration by Keera Ratnam