by Sachi Sri Kantha, May 8, 2020

Front Note:

My father Siva Sachithanantham (1923-2003) was a fan of G.G. Ponnambalam’s theatrics in the political platforms and legal arena. He developed this fascination during the 1930s (when he was a teenager, and ‘Ponnan’ was his first local political hero), when Ponnambalam first contested the Point Pedro seat in 1934 and 1936 for State Council elections. Forty years later in 1976, when Ponnambalam appeared at the Trial at Bar case in Colombo defending Amirthalingam and his three Federal Party colleagues (V.N. Navaratnam, K.P. Ratnam and K. Thurairatnam), my father urged me to go and ‘watch’ how Ponnan talks in English, as this could be the last chance for me to see him in ‘action’. While living in Colombo, for some silly reason, I disobeyed my father’s request and he was correct indeed. Now I regret why I missed ‘watching’ Ponnan’s ‘last grandstanding performance’.

Introduction

One year after the death of G.G. Ponnambalam on Feb. 9, 1977, Tamil journalist Reggie Michael summed up Ponnampalam’s trail-blazing career as follows:

G.G. Ponnambalam (lt) and S.J.V. Chelvanayakam (rt) (circa 1947)

“Ganapathipillai Gangesar Ponnambalam belonged to a different age and different atmosphere. He was the last cut-post of a fading parliamentary frontier ruled by the golden tongue and flamboyant personality. We shall not hear again the rich velvet of his voice cushioning the pungent phrase; his studied and sonorous boom stalking the hapless foe; the peerless parry and thrust in the duel of debate; the stab of lethal sarcasm that struck fear within the portals of parliament as much as within the wall of courts. Nor shall we hear those purple patches of oratory such mesmerized the Soulbury Commission and spurred them to ask for an encore; those flights of eloquence such dazzled the distinguished audience at the United Nations in 1965…”1

G.G. Ponnambalam, the son of a post master was born in Alvai, Point Pedro on November 8, 1902. His mother was from Navaly, Manipay. Though 43 years have passed since death, a worthy biography for him has not appeared so far. What is available now are only partial descriptions of his political activities penned by Alfred Jeyaratnam Wilson (1928-2000), political scientist2,3 and a chronicler of Sri Lanka’s 20th century history. While Wilson’s observations are worthy for evaluation on the conflict Ponnambalam had with his then lieutenant and later antagonist S.J.V. Chelvanayakam (1898-1977), the fact that Wilson’s works may suffer from kinship bias should also be considered. Chelvanayakam was the father in law of Wilson. With due respect to his scholarship, Wilson’s descriptions (1988 and 1994) of Ponnambalam’s status as the first popular Eelam Tamil leader deserve a review.

Thus, I provide this appraisal of the power and plight of Ponnambalam, 89 years after he made his first failed attempt to enter the legislature of Ceylon, at the age of 28. This re-appraisal is badly needed because the current Wikipedia entry on G.G. Ponnambalam [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/G._G._Ponnambalam, accessed May 8, 2020] hardly does justice to his stature, especially due to anti-Hindu bias and censoring tactics practiced by a Tamil Wikipedian prig with the handle name Obi2canibe [aka Prof. Ratnajeevan Hoole].

DMK leader Karunanidhi’s elegy to G.G. Ponnambalam

Ponnambalam’s Stature as a Tamil Leader

Following the introduction of universal suffrage to colonial Ceylon in 1931, Ponnambalam became the first politician to have mass appeal among the Eelam Tamils. Thus his electoral record between 1931 and 1970, spanning four decades, is worthy of review.4 As of now, none among the Eelam Tamil politicians had faced the voters repeatedly for such a lengthy duration without switching party affiliations. If current TULF leader R. Sampanthan contests the forthcoming general election scheduled for June 20th, he will complete 43 years of facing the voters repeatedly in the same party. Ponnambalam’s public service to Tamils can be dissected into four phases.

Phase 1: Period of ascendancy (1931-1943) as Member for Point Pedro

During this phase, Ponnambalam faced three elections to the State Council of Ceylon. He won two in 1934 and 1936, after losing at his first attempt in 1931. Following the boycott decision made by the Jaffna Youth League in April 1931 in the Northern Province, election was held in June 20, 1931 for the Mannar-Mullaitivu constituency.5 Ponnambalam stood against S.M. Ananthan.

The First State Council election for the Mannar-Mullaitivu constituency, held in June 20, 1931.

Total electorate 16,476; Total votes polled 10,314; Percent polled 62.60. The result was:

S.M. Ananthan 5,647 votes

G.G. Ponnambalam 4,667 votes

Vote margin for Ananthan 980 votes.

Following the lifting of the boycott, Point Pedro constituency by-election was held on April 5, 1934.

Total electorate 26,837; Total votes polled 11,351; Percent polled 39.36. The result was as follows:

G.G. Ponnambalam 9,319 votes

Sri Pathmanathan 2,032 votes

Vote margin for Ponnambalam 7,287 votes.

He received 82 percent of the votes polled and entered the First State Council at the age of 31. Election was a new experience for the masses and only 39 percent of the voters in Point Pedro constituency exercised their rights. Following the death of Sir. Ponnambalam Ramanathan, Eelam Tamils were devoid of a ‘voice’ and it was left to Ponnambalam to fill this vacuum. Less than two years later, the Second State Council election for the Point Pedro constituency was held in February 22, 1936.

Total electorate 44,767; Total votes polled 21,036; Percent polled 46.99. The result was as follows:

G.G.Ponnambalam 14,029 votes

K.Balasingham 7,007 votes

Vote margin for Ponnambalam 7,022 votes.

He retained the Point Pedro seat convincingly by receiving 67 percent of the votes polled. His career as a Tamil leader of stature began to blossom during the subsequent eight years.

Phase 2: Period of peak (1944-1953) as Member for Point Pedro and then Member for Jaffna

Ponnambalam faced two general elections in 1947 and 1952 and won both. From Point Pedro electorate, he had moved to contest the Jaffna electorate. In 1947, Ponnambalam’s opponent was Sir Arunachalam Mahadeva and this contest became the ‘prestige battle’ of that era. Ponnambalam defeated Mahadeva by the largest majority he ever received in the elections. Then he was aged 45. The catch phrase for this campaign was a play on the Tamil word ‘Palam’(strength or vigor), which rhymed with his name – ‘Engal Palam – Ponnambalam’ [Our Strength is Ponnambalam].

1947 General election: Jaffna constituency

Total electorate 42,546; Total votes polled 19,681; Percent polled 46.26. The result was:

G.G. Ponnambalam (TC) 14,324 votes

A. Mahadeva (UNP) 5,224 votes

Vote margin for Ponnambalam 9,100 votes.

Ponnambalam received nearly 73 percent of the votes polled. One year after the election, he was inducted into the D.S. Senanayake Cabinet as the Minister of Industries and Fisheries on Sept.3, 1948.

1952 General election: Jaffna constituency

Total electorate 29,489; Total votes polled 21,131; Percent polled 71.66. The result was:

G.G. Ponnambalam (TC) 12,726 votes

E.M.V. Naganathan (FP) 8,317 votes;

Vote margin for Ponnambalam 4,409 votes.

Ponnambalam’s glamour was beginning to fade, though he contested the 1952 election as a Cabinet minister. In this election, his share of votes had fallen to 60 percent. Once his loyalist Dr. Naganathan, contesting in the newly formed Federal Party ticket turned out to be a tougher opponent than A. Mahadeva in 1947. Following John Kotelawala’s ascendancy to prime minister rank on Oct.14, 1953, Ponnambalam quit as the Minister of Industries and Fisheries on Oct.22, 1953, after serving a little more than five years. It was said that Kotelawala had a grudge on Ponnambalam, because the latter overlooking the seniority of Kotelawala (after the death of D.S. Senanayake) promoted the candidacy of the dead prime minister’s son Dudley Senanayake, who succeeded his father in 1952.

Phase 3: Period of descendancy (1953-1970) as Member of Parliament for Jaffna and then as non-MP

Ponnambalam faced five general elections; namely 1956, March 1960, July 1960, 1965 and 1970, always contesting from the Jaffna constituency. He could win only in 1956 and in 1965. He lost twice in 1960 and also in 1970. Between 1931 and 1952, he was involved in direct contests and he won four out of five times. From 1956, Ponnambalam had to face multi-cornered contests, involving spoilers belonging to the Leftist parties and an upstart Independent, Alfred T. Durayappah.

1956 General election: Jaffna constituency

Total electorate 34,804; Total votes polled 22,178; Percent polled 63.72. The result was:

G.G. Ponnambalam (TC) 8,914 votes

E.M.V. Naganathan (FP) 7,173 votes

Kartigesan (CP) 3,239 votes;

Visuvanathan (LSSP) 2,703 votes

Vote margin for Ponnambalam 1,741 votes.

By 1956, the writing was on the wall that Ponnambalam had lost his glamour and it was only a matter of time that he would face defeat. In a span of 9 years, his vote margin, which was 9,100 in 1947 had been drastically reduced to 1,741; he won on a plurality by garnering only 40 percent of the votes polled. He was 54 then. The noose tightened on him, with the demarcation of Nallur as a separate electorate in 1960, which saw two general elections.

1960 March General Election: Jaffna constituency

Total electorate 24,299; Total votes polled 17,473; Percent polled 71.97. The result was:

A.T. Durayappah (Independent) 6,201 votes

G.G. Ponnambalam (TC) 5,312 votes

Kathiravelupillai (FP) 5,101 votes

Visuvanathan (LSSP) 767 votes

Vote margin for Durayappah 889 votes. Ponnambalam was defeated for the first time in Jaffna in this election. He received only 30 percent of the votes polled and lost to Durayappah. He was aged 57. Due to a hung parliament, another election followed soon.

1960 July General Election: Jaffna constituency

Total electorate 24,299; Total votes polled 18,056; Percent polled 74.31. The result was:

A.T. Durayappah (Independent) 6,313 votes

G.G. Ponnambalam (TC) 6,015 votes

Kathiravelupillai (FP) 5,644 votes

Vote margin for Durayappah 298 votes. Compared to March 1960, Ponnambalam polled 703 votes more, but it was not enough to get him elected. Durayappah won with a reduced majority of 298 votes. These two successive defeats at the hands of a novice, Independent Durayappah sealed the political career of Ponnambalam, which had blossomed in 1934. When the 1965 general election came, he had turned 62.

1965 General Election: Jaffna constituency

Total electorate 28,473; Total votes polled 22,141; Percent polled 77.76. The result was:

G.G. Ponnambalam (TC) 9,350 votes

C.X. Martyn (FP) 6,800 votes

A.T. Durayappah (Independent) 5,918 votes

Vote margin for Ponnambalam 2,550 votes. Ponnambalam was able to taste a win at this Election, by receiving 42 percent of the votes polled. But, the five year period between 1965 and 1970 turned out to be the sunset phase of Ponnambalam’s distinguished political career. When the 1970 general election came, he had turned 67. Rather than taking a bow and retiring from the arena, still he opted to dance on the Tamil political stage.

1970 General Election: Jaffna constituency

Total electorate 31,214; Total votes polled 24,938; Percent polled 79.89. The result was:

C.X. Martyn (FP) 8,848 votes

A.T. Durayappah (Independent) 8,792 votes

G.G. Ponnambalam (TC) 7,222 votes

Vote margin for Martyn 56 votes. In the final election he faced, Ponnambalam was pushed to third place and was rejected by Jaffna voters for the third time. Martyn of the Federal Party narrowly defeated Durayappah by a whisker of 56 votes. Ponnambalam’s 1965 victory in Jaffna had given him pseudo-confidence that Jaffna voters would not reject him. But that was not to be so. If he had opted to contest from Point Pedro, he might have had a better chance of being elected, since the Federal Party’s popularity was relatively weak in the Point Pedro segment of the peninsula. Also the nostalgia factor of being a native son returning to his birth soil would have worked in his favor. But Ponnambalam being Ponnambalam, he had his pride and would not leave Jaffna for being taunted as a ‘retreat step’. Thus, Ponnambalam’s political tent came to be folded. Following his electoral defeat, he spent more time in Malaysia during the next five years.

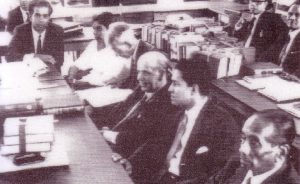

The ‘Dream Team’ of Trial-at-Bar case (1976) against Amirthalingam. (Rt to Lt) – G.G. Ponnambalam, K. Kanag-Isvaran, M. Tiruchelvam, S.J.V. Chelvanayakam, Shanthini Gnanakaran, R. Balasubramaniam

Phase 4: Swan song as Legal Luminary in 1976

Between 1970 and 1976, many vital events happened in the political arena in Sri Lanka, that concerned Eelam Tamils. Four prominent ones were, (1) Introduction of the 1972 Republican Constitution, followed by emergence of the Tamil student movement in response to state oppression, extension of parliament by two additional years, (2) By-election for the Kankesanthurai constituency in Feb. 1975, (3) assassination of Ponnambalam’s erstwhile opponent Durayappah in July 1975, and (4) arrest of three Federal Party MPs (V.N. Navaratnam, K.P. Ratnam and K. Thurairatnam) and two ex-MPs A. Amirthalingam and M. Sivasithamparam by the Jaffna police on May 21, 1976 on the charges of allegedly distributing literature discouraging the public from attending the Republic Day public celebrations. Apart from Sivasithamparam, other four were charged on five counts, two of which were described as contraventions of Emergency (Prevention of Subversion) Regulations. A Trial-at-Bar case was hoisted on them. This brought Ponnambalam for a swan song performance in the public arena. He had been elected as one of the co-Presidents of the newly formed Tamil United Liberation Front (TULF).

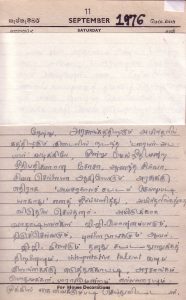

Sachi’s diary entry in Tamil, for Sept.11, 1976

The Trial-at-Bar case began on July 12, 1976 at the High Court of Colombo. Ponnambalam had reached 74 and was ailing. After his death, a fellow lawyer A.H.C.de Silva, QC, had observed that he had persuaded Ponnambalam to take a less active role in the Trial-at-Bar case. To quote de Silva:

“In the Trial-at-bar case I tried hard to prevent him [Ponnambalam] from taking a leading and an active part and suggested to him to be present only in a consultative capacity while someone else argued the important questions of law involved, as I felt that the strain of arguing his matter would be too much for him having regard to the fact that he had had a very serious illness only a few months back when he nearly passed away.

I also felt the argument would take a number of days and that this would impose a heavy strain on him, but he told me that he had already undertaken to argue this case and he would have to go through with it and did so. The submission took many days and I have no doubt that the effect seriously undermined his health. It was a surprising performance by a man who nearly died only a few months earlier. Such was his devotion to duty.”5

It may be inferred that Ponnambalam’s devotion to duty as well as his interests on leading a battle for a Tamil cause, overruled the overtures made by some of his Sinhalese friends to play it calm. The High Court at Bar, on September 10, 1976, upheld a defence objection on the validity of the Emergency Regulations and Appapillai Amirthalingam, the Secretary General of TULF, was discharged of charges of possessing and distributing seditious literature. [see my diary entry in Tamil, for Sept. 11, 1976, provided nearby]. Mr. K. Kanag-Isvaran, President’s Counsel, in his speech made on Feb.9, 2008, ‘The Tiruchelvam I Knew’ had given a synopsis of the decision given by High Court Judges Joseph Francis Anthony Soza, H. Aruna G. de Silva and Siva Selliah.[ http://mtiruchelvam.com/review_by_k_kanag-isvaran]

Amirthalingam, the first accused, paying tribute to Ponnambalam’s skill at the end of the trial noted:

“During the case, Mr.G.G. Ponnambalam convinced us that we should attack the way the Emergency was proclaimed. The Emergency was hated and repugnant to both Sinhala and Tamil. By contesting the validity we hoped to win some of the Sinhala people also to be sympathetic to our cause. We were fighting their case too.”6

The three High Court Judges unanimously ruled, in a 67-paged judgement that they could not continue to exercise any further jurisdiction in the case to try the accused. They held that the Emergency Regulation 59, gazetted in May 1976 by which the Court was created ‘can have no sanction or validity in law’. Then the Attorney General Siva Pasupati appealed for a revision of the High Court-at-Bar order in the case against Amirthalingam. The Attorney General argued that when one had to strike a balance between the security of the state and the liberty of the subject, there was no question that the security of the state must take precedence. On December 10, 1976, the five judge Bench, by a unanimous verdict, held that the proclamation of the state of Emergency was valid. Soon after the judgements were delivered, the Attorney General announced that the Government will not be proceeding the case against the four FP leaders relating to the possession and distribution of seditious literature.

F.R. Jayasuriya, a staunch agitator for ultra-Buddhist causes, summed up the embarrassing position in which the Government was placed at the end of the Trial-at-Bar case, as follows:

“When it came to the most fundamental need of the government to have the right in a crisis, to declare a state of Emergency – even this simple, elementary and vital matter became the subject of one of the most important constitutional battles of recent years, when the sick and ailing leader of the Tamil Congress was carried from his sick-bed to argue the case before the Supreme Court, whose judgement alone saved the Government and prevented the country from being thrown into governmental and administrative chaos, but also advised the Government to have the ambiguous clause amended.”7

This was a compliment for the legal acumen of Ponnambalam who embarrassed the then Government in a court of law, even when he was ailing.

When it came to identifying solutions for the political problems of Eelam Tamils, Ponnambalam was a visionary – sometimes even ahead of Chelvanayakam. As observed by S.P. Amarasingam, the editor of Tribune, in the aftermath of Kankesanthurai by-election in February 1975,

“…Chelvanayakam does not believe in separation. The call for a separate state had first come from Suntharalingam and it was later weakly echoed by TC’s G.G. Ponnambalam. The FP had fought this separatism with its federalism. But now the TUF has an open mind on federalism as well as a separate state…”8

While living in Malaysia, Ponnambalam was preparing to visit UK, and fainted while on his visit to arrange the visa travel document at the British consulate on February 7th, 1977. He underwent an operation at a hospital and died early morning 3:30 am on February 9th, 1977. His remains were brought to Colombo on February 11th (Friday) and kept for public viewing at his house in No. 15, Queen’s Road, Colombo 3. Since he represented two constituencies in Jaffna (Jaffna and Point Pedro) in his lengthy political career, on February 12th (Saturday), Ponnambalam’s remains were first taken to Jaffna by plane. After one day of public viewing at Veerasingham Hall, the following day February 13th (Sunday), his remains were taken to his native place Point Pedro and cremated at the beach, around 7:50 pm. His son Kumar lit the funeral pyres. Amirthalingam delivered the funeral oration. He said, ‘Towards the end of his life, message left by G. G. for us was three mantras- unity, self-respect and liberation. Our Tamil United Front functions on the basis of these three mantras. Yes, ethnic unity, self-respect and ethnic freedom were the three vital assets Ponna had left for us. Based on these, we serve for the liberation of Tamil ethnics.’9 DMK leader M. Karunanidhi also wrote an elegy to Ponnambalam.9

Ponnambalam’s Power

Though it has not been thought of seriously until now, Ponnambalam has to be credited as a Gandhian style agitator in the pre-Independent era, before Chelvanayakam. Two aspects of his Gandhian strategies deserve merit. First, like Mahatma Gandhi who woke up the down-trodden Indian populace with his ‘Never fear’ admonition, Ponnambalam introduced the ‘Tamil pride’ to the sedate Eelam population, then untutored about the universal franchise. His catch phrase, Thamilan enru sollada; Thalai nimirnthu nillada [Say you are a Tamilian and Stand holding your head high] was an epoch-turning mantra for Eelam Tamils in 1947. This fact has been acknowledged by Wilson.

Secondly, Ponnambalam, rather than being a meek collaborator or ‘fence-sitter’, agitated and negotiated for equal rights for Eelam Tamils with the British administrators. That he was not successful in his venture shouldn’t take away his acumen in arguing the case for the people he represented. This fact has not been acknowledged by analysts like Wilson and K.M. de Silva. They stress only the angle of Ponnambalam ‘overplaying his card’ and not satisfying the mood of the wily British administrators. That Ponnambalam also shared Gandhi’s fate in his negotiations with the British imperialists is easily visible. Both were ‘cheated’ (if that is the proper word) by the British Poo Bahs. Gandhi was outmaneuvered by the British who carved a Pakistan by their imperial game of ‘Divide and Rule’. Similarly, Ponnambalam was outfoxed by the British Poo Bahs, by their adamancy of turning a deaf ear to Ponnambalam’s plea for ‘balanced representation for the minorities’ in their blundering approach to colonial constitution making.

Wilson has recorded that Sir Ivor Jennings – the internationally recognized constitutional expert was partial to the interests of D.S. Senanayake (transformed ‘from rebel to a conservative collaborator of the British’) and O.E. Goonetileke, as opposed to Ponnambalam. Also, the established facts that the then British Governor Andrew Caldecott (1884-1951) during his tenure (1937-1944) did not like Ponnambalam reveal that Ponnambalam was a non-collaborator of the British designs, but a confrontational agitator in the Gandhian mould. The British rulers in the 1930s did not like Gandhi as well for his confrontational stance.

Apart from Prof. Wilson’s two books cited already, Ponnambalam’s political activity between 1931 and 1947, had received some coverage in Jane Russell’s book, ‘Communal Politics under the Donoughmore Constitution 1931-1947’, published in 1982.10 She mentions that she had interviewed Ponnambalam on March 14, 1974, for some details included in her work. [This was a doctoral thesis submitted to the University of Peradeniya in 1976.] What was interesting to me was Jane Russell’s citation of Ponnambalam’s verbal duels in the parliament. I provide excerpts that appear in page 157 of this book, because it provides some details about Hitler surrogates among the Sinhalese politicians who had designs on suppressing the rights of Tamil in Ceylon. To quote,

“ The Hitlerian philosophy and rhetoric considerably affected communalist rhetoric in Ceylon. G.G. Ponnambalam said in Council in 1939:

‘This is our home. We are inhabitants of this country and we have as much right to claim to have permanent and vested interests in this country, politically and otherwise, as the Sinhalese people. We do not propose to be treated as undesirable aliens. We will not tolerate being segregated into ghettos and treated like Semites in the Nazi states.’ (Hansard, 1939, col. 890)

In January 1939 at a meeting in Balapitiya, [S.W.R.D.] Bandaranaike aooeaked the electors in this vein:

‘I am prepared to sacrifice my life for the sake of my community, the Sinhalese. If anybody were to try to hinder our progress, I am determined to see that he is taught a lesson he will never forget.’

At the conclusion of the meeting, a lady in the audience, Mrs. Srimathie Abeygunawardene likened Mr. Bandaranaike to Hitler and appealed to the Sinhalese community to give him every possible assistance to reach the goal of freedom. (Hindu Organ, January 26, 1939). This reported remark caused G.G. Ponnambalam to term Bandaranaike ‘the pocket Fuehrer’ (Hindu Organ, May 24, 1939).”10

Ponnambalam’s taunt of Bandaranaike as ‘the pocket Fuehrer’ in 1939 was apt indeed. That Adolf Hitler’s verbal demagoguery of Aryan dominance did influence quite a number of Sinhalese orator-politicians like Bandaranaike (1930s to 1950s), K.M. P. Rajaratne (1950s) and Ranasinghe Premadasa (1960s to 1980s) and Buddhist Bhikkus, is a fact that remains hidden in the text books on contemporary Sri Lanka.

Ponnambalam’s Plight

Ponnambalam’s decision in joining the D.S. Senanayake’s Cabinet in mid-1948 and subsequent downfall in popularity among the Eelam Tamils can be attributed to at least four factors.

First, though electorally he represented the Jaffna Tamils he came to be influenced more by the Colombo Tamils as well as his non-Tamil contacts in Colombo. Ponnambalam had catered to this constituency in the legal arena and they paid him well for his legal acumen. Thus, he turned to be a ‘drifter’ from Jaffna to Colombo.

Secondly, what psychologist Carl Jung recognized as ‘mid-life crisis’ may have had an adverse influence on Ponnambalam. By mid 1948, he was about to reach 45. As Wilson had observed3, Ponnambalam by then had spent 14 years in the Opposition benches, and the ‘carrot’ of Cabinet position was too tempting for him to reject. Contrastingly, Chelvanayakam was then a new-face in the 1947 Parliament.

Thirdly, due to his flamboyant personality, Ponnambalam never bothered to nurture his beliefs beyond the territory of Jaffna peninsula. Thus, he never pulled the ‘next generation’ within his fold, like Chelvanayakam did.

Fourthly, the unanticipated leadership changes within the UNP (from D.S. Senanayake to Dudley Senanayake to John L.Kotelawala) between March 1952 and October 1953 – a short span of 18 months – pulled the rug below Ponnambalam’s ‘Cabinet perch’ beyond redemption.

Conclusion

Following the introduction of universal suffrage in the island, Ponnambalam became the first Tamil leader to have mass appeal among the voters. That being a pioneer in an unchartered political territory, he did fumble occasionally is undeniable. In his quest to find a legitimate political future for Eelam Tamils, Ponnambalam had to face rivals and nit-pickers among Tamils (such as E.R. Tambimuttu from Batticaloa, Jaffna Youth Congress activists in 1930s, subsequently the Federal Party activists in 1950s and Sinhalese collaborator Alfred Thuraippah in the first half of 1960s), none of whom could match his charisma and flamboyancy. Like any great political leader (Abraham Lincoln and Winston Churchill for example), Ponnambalam was not without fault. As such, in the political arena, he did taste both success and defeat. Between 1931 and 1970, Tamil voters elected him six times and spurned him four times.

The singular fact that it was he who introduced Chelvanayakam into Eelam Tamil politics has to be noted as one of his meritorious deeds. Chelvanayakam, though chronologically 4 years older than Ponnambalam, died two months later after Ponnambalam in 1977. Also the fact that rather than being a collaborator with the colonial British administrators or functioning as a ‘fence-sitter’ marking time, Ponnambalam practiced Gandhian-style agitational politics in the pre-Independence era deserve due recognition. His life badly deserves a full length biography.

Foot Notes

Abbreviations to political parties: Communist Party – CP; Federal Party – FP; Lanka Sama Samajist Party – LSSP; Tamil Congress – TC; United National Party – UNP.

- Sunday Observer, Colombo, Feb.19, 1978.

- J.Wilson: The Break-Up of Sri Lanka – The Sinhalese Tamil Conflict, C.Hurst & Co, London, 1988, 240 pp.

- J.Wilson: S.J.V.Chelvanayakam and the Crisis of Sri Lankan Tamil Nationalism 1947-1977 – A Political Biography, Hurst & Co, London, 1994, 149 pp.

- Electoral results were gleaned from, G.P.S.H.de Silva: A Statistical Survey of Elections to the Legislatures of Sri Lanka, 1911-1977, Marga Institute, Colombo, 1979.

- M.de Silva: History of Sri Lanka, C. Hurst & Co. London, 1981, p.427.

- Himmat, Bombay, Jan.7, 1977.

- Sun, Colombo, July 18, 1977.

- Tribune, Colombo, Feb.15, 1975.

- Putholi (N. Sivapatham): Thamilar Thalaimagan G. G., 2nd, Dhamayanthi Publishers, Atchuveli, 1977 (in Tamil).

- Russell: Communal Politics under the Donoughmore Constitution, 1931-1947, Tisara Prakasakayo Ltd., Delhiwala, 1982, 358 pp.