Prabhakaran’s battlefield adversary from India

by Sachi Sri Kantha, April 5, 2021

Introductory Note

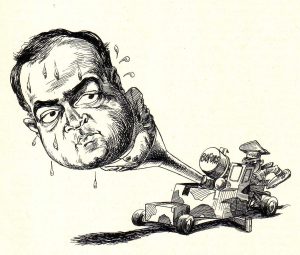

I provide a dossier of six items on Gen Krishnaswamy Sundararajan (aka Sundarji). He was a Tamilian by birth. Born in 1928 at Chingleput, Tamil Nadu, Sundarji’s 93rd birthday falls on April 28th. When the Indian Peace-Keeping Force (IPKF) was dispatched to Jaffna in 1987, Sundarji held India’s Chief of Army rank. He retired on May 31, 1988. Thus, Sundarji became the first and only Tamil military adversary for Prabhakaran.

Between May 1976 and May 2009, Prabhakaran faced a total of 12 adversaries from the Sinhalese army. Eleven among these retired without defeating Prabhakaran’s LTTE army. One record that eludes all the bombast of these 12 Sinhalese army generals Prabhakaran faced, was that they never tested their military strength and guile against another nation. Prabhakaran remains the one and only Sri Lankan (or Eelam) military general, at the young age of 33, to tackle another nation’s army for more than two years and gain prestige. Considering the current trends, Prabhakaran’s record will hardly be bettered by any Sinhalese military general, for decades or even centuries to come.

General Krishnaswamy Sundarji obit., India Today, Feb 22, 1999

Even by Indian standards, the hyperbole recording Gen Sundarji’s career, which appeared when he retired from the Indian Army on Feb 1988, was unbelievable. “He had the flamboyance and showmanship of a Patton, the drive and conceptual vision of a Rommel, the stubbornness and ego of a Churchill, the ambitious hawkishness of a MacArthur and the manipulative skills of a politician.” It was as if, the 20th century India had produced a military mind combining the talents of Patton, Rommel, Churchill and MacArthur. But, Gen Sundarji met his match in Prabhakaran on October 1987. And the eventual outcome tarnished the image of Sundarji.

It is not rocket science to comprehend why Prabhakaran’s LTTE had bad press, with the Indian media barons and the pampered pundits in New Delhi. It was because he was the only one to prick the delusionary bubble in which the India’s image makers thrived; while preaching Gandhian non-violence and simultaneously suppressing the Eelam freedom movement by violent deeds instigated by the RAW gumshoes and South Block mandarins.

Nevertheless, in the honored tradition of paying due respect to a rival military chief, as a LTTE chronicler, I present this dossier of six items related to Gen. Sundarji’s career in Indian army.

Item 1: ‘General Sundarji leaves behind a legacy most fiercely disputed in the history of the army’, by Inderjit Badhwar and Dilip Bobb, India Today, May 15, 1988.

Item 2: ‘The gun that can kill at four years’ range’, by India Correspondent, Economist, Sept. 9, 1989, pp. 35-36.

Item 3: ‘Heavily shelled by Bofors’, by Edward W. Desmond, Time (International edition), Sept 25, 1989, p.12.

Item 3: ‘Heavily shelled by Bofors’, by Edward W. Desmond, Time (International edition), Sept 25, 1989, p.12.

Item 4: ‘Soldier of the Mind’ by Shekhar Gupta. Indian Express, Feb.10, 1999.

Item 5: Warrior as scholar, by Manoj Joshi, India Today, Feb.22, 1999, p. 33.

Item 6: Milestones, by Hannah Beech, Time (Asia edition), Feb.22, 1999, vol. 153, no.7

**************

Item 1:

General Sundarji leaves behind a legacy most fiercely disputed in the history of the army

Inderjit Badhwar and Dilip Bobb, [India Today, May 15, 1988]

He had the flamboyance and showmanship of a Patton, the drive and conceptual vision of a Rommel, the stubbornness and ego of a Churchill, the ambitious hawkishness of a MacArthur and the manipulative skills of a politician. It was to prove a highly potent potion.

Last week, when he finally stepped down as chief of army staff, General Krishnaswami Sundarji, 60, left behind a legacy that is the most fiercely disputed and controversial of any chief in the history of the Indian Army.

The reasons are not difficult to target. Not since Sam Maneckshaw has an army chief proved to be so high-profile which, in the context of the Indian Army, is in itself a major variation. Moreover, not even Maneckshaw managed to influence so markedly, by the sheer force of his personality, the political leadership in the country.

No other general in the Indian Army possessed the intellectual depth and strategic perceptions that Sundarji displayed, attributes that earned him the undisputed reputation of being a “thinking man’s general”. No other chief has succeeded in introducing the kind of major changes in strategy, perceptions and structure that Sundarji did in his 820-day tenure.

But governing all this is the obvious fact that under no other previous chief has the Indian Army been stretched to such unprecedented limits and faced such daunting operational challenges.

Starting with the massive Operation Brasstacks in the winter of 1986, the fierce but covert ongoing battle in the wastes of Siachen, a high level of tension along the Sino-Indian border and the launching of Operation Pawan in Sri Lanka that has tied down a total of 80,000 Indian troops in another country, the army faces, more than at any period since 1962, its greatest test ever: of men, of morale, of machines. And more than all else, of the wide-ranging conceptual changes that Sundarji pushed through.

It is these that are currently the subject of major controversy and debate, within the army and the Defence Ministry. Opinions are, naturally, sharply divided – which can only be the case with a man of Sundarji’s personality and ambition. There are those in the army, including senior generals, who accuse him of personal ambition and slick showmanship – a death and glory boy whose desire for honour in history took the country the closest it has been to war (with Pakistan during Operation Brasstacks) in the last 16 years.

There are also those who credit him with getting the army, for the first time, into a “thinking phase”, the first general to introduce a long term 15-year perspective plan, a man who has introduced new and exciting concepts of strategy and mobile warfare, a man who has succeeded in pushing modernisation of equipment and strategy and given the army a much greater say in the country’s geopolitical ambitions.

What then will history say? Will Sundarji go down as the man who dragged the army by its bootstraps into the 21 st century? Or will it record the fact that here was the ultimate cold warrior who ignored advice, ignored tradition, ignored the other two services and, indeed, ignored reality in pursuit of his personal convictions?

So wide-ranging and far-sighted were Sundarji’s ideas and impact on the army that only history can ultimately provide the final answer. He himself admits: “I deliberately set my sights very high and it was unrealistic to imagine I could achieve what I set out to do.” But in the process, Sundarji promised much more than he actually delivered. He has certainly upset a very major proportion of senior serving officers and the traditional structures that the army has established throughout its long and prideful history.

He has left himself open to the charge that he pushed too many things too fast for a massive organisation like the Indian Army to absorb, let alone understand; that his obsession with hi-tech razzle-dazzle and operations and concepts on a massive and expensive scale ignored the more crucial aspects of the overall role of the army. More than anything else, Sundarji has set in motion a process of change that will be almost impossible to alter or modify should some of them ultimately prove unrealistic or unworkable.

In themselves, the changes are significant and wide-ranging. They include:

- The introduction of a 15-year perspective plan that covers every possible future operational contingency as well as the induction of suitably updated weaponry. This plan has also involved the navy, the air force, Defence Research and Development and Defence Production.

- A massive push towards mechanisation and mobile warfare and the updating of armoured warfare concepts.

- The raising of the army’s first Mechanised Infantry Division.

- Staging the most elaborate exercises in the history of the army.

- The establishment of the Army Aviation Corps controlled and operated by the army, a long-standing demand that only fructified during Sundarji’s tenure.

- Large-scale computerisation at senior command levels and in the field to provide up-to-date information and real-time intelligence.

- The reorganisation of the 54 Infantry Division as an Air Assault Division.

- The introduction of the rapids (Reorganised Army Plains Infantry Division) concept, a compact, integrated formation that provides greater flexibility, mechanisation, mobility, firepower and air-land battle capabilities.

- The introduction of new tactics emphasising speed of movement, firepower and manoeuvrability.

- The restructuring of the traditional command-staff stream that has seen staff officers posted in the field and vice versa.

- An infinitely more aggressive military posture (called ‘forward posture’) vis-a-vis Pakistan and China as part of the new ‘dissuasive and deterrent’ policy.

- The restructuring of the army’s Parachute Regiment into three para-commando battalions modelled along the lines of the British Special Air Services.

There can be no contesting that many of these changes were long overdue and, in fact, necessary in what is an increasingly militarised environment. Says Air Commodore Jasjit Singh, director of the Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses: “What is remarkable is that there is now greater togetherness in thinking in the three services. They are all looking ahead. They’re talking about more integration and coordination.”

The credit for that undoubtedly goes to Sundarji and very few dispute it. Adds a senior serving general: “Sundar’s greatest achievement is that he started the army thinking, thinking about concepts, about strategy and about the future. Nobody can question his intellectual credentials.”

But though senior officers are unanimous in giving him credit where it is due, they are also virtually unanimous in labelling him an impulsive officer whose ambitions and elaborate ideas could have eventually proved dangerous for the army, and in some cases, already have. Sundarji has all along had a reputation for rushing in where others feared to tread, often with little thought for the long-term consequences.

And that is exactly where the controversy lies. Says Lt-General Mathew Thomas, one of Sundarji’s closest friends and one of India’s most highly decorated soldiers who edits the Indian Defence Review: “Sundarji has always been too much in a hurry. He is always infused with the euphoria of doing something immediately and in the public eye.”

That has undoubtedly been the hallmark of Sundarji’s tenure. The first time he shot into national prominence was in June 1984, when he masterminded Operation Bluestar, the assaulton the Golden Temple, as head of the army’s Western Command. He had already, by then, caught the imagination of Mrs Gandhi through Operation Dig vijay, an exercise in 1983 in which he moved large armoured columns at very high speeds and over distances that no Indian armoured regiment had moved before. Even in the last two wars with Pakistan, the maximum distance of Indian armour had been 15 km a day. During Operation Digvijay, Sundarji pushed that up to 90 km between dusk and dawn.

Though most army strategists question the operational efficacy of such rapid movement in actual battle conditions, it impressed the political leadership enough to put him in charge of Operation Bluestar. Militarily, and politically, Bluestar was badly handled and carried Sundarji’s unmistakable stamp: the excessive use of heavy armour, little concern for logistical detail and intelligence and the element of over-confidence (he had told Mrs Gandhi that the operation would be completed in a day).

Senior army commanders who took part in the operation say that it was launched in too much of a hurry when not enough intelligence was available. The commando force was not provided with adequate maps of the temple and the layout. The assault force was issued 1960 vintage gas masks and 1957 vintage smoke bombs, most of which never exploded. Another major error was in sending frogmen with snorkels to go underneath the shallow

And narrow sarovar where they were sitting ducks for the well-entrenched militant force.

Sundarji denies that intelligence was poor, a claim widely disputed by senior soldiers involved in the operation. But Sundarji does admit that the assessments given to him of the motivation of the militants and their capacity to withstand the siege and inflict heavy casualties were inadequate.

Despite that, Sundarji was destined for higher honour. There was little doubt that he was the only general who would have gone into the temple without questioning the timing or the methods to be employed. A wide range of serving officers interviewed by India Today say that it was a situation where the army should have put its foot down. Says a serving general: “Somebody should have had the moral courage to say ‘Not the army’. The political consequences will be unbearable for the country. At the army commander level you have to think in terms of the larger national perspective.”

But Sundarji’s star was already on the ascendant, not only because of the way he had impressed the political leaders but also because of his close rapport with former army chief, General Krishna Rao – both belong to the Mahar Regiment – and Sundarji’s obvious brilliance as a military strategist. He had been given command of the army’s most prestigious armoured divisions and he became the first infantry officer ever to command an armoured division (Ist Armoured Division). His appointments had included a stint in the Congo with the United Nations’ forces, instructor at the Infantry School in how, the Staff College, Wellington, and Commandant, College of Combat, where he proved himself a great innovator and produced papers that reflected his advanced military thinking. He had also been selected for a course at Fort Leavenworth in the US.

It was during Krishna Rao’s tenure as army chief that Sundarji made his presence solidly felt in South Block when he was brought in as deputy chief. Krishna Rao. according to senior officers, leaned heavily on Sundarji who, in effect, functioned as his chief of staff. Sundarji was thus in a position to decide on senior appointments and many of these, according to his detractors, were people who were loyal to him personally. It was, by now, evident that Sundarji was being groomed to take over as chief.

His posting as head of Western Command was to give him exposure as an army commander in what was India’s largest and operationally most sensitive military theatre.

After General Arun Vaidya took over as army chief, Sundarji was brought back to army headquarters as vice-chief. Critics say that it was in this capacity that his manipulative skills became evident. He ensured that all the director-generals of other services – Artillery, and Army Supply Corps – reported directly to him.

But it was really after his appointment as chief of army staff in February 1986 that Sundarji’s ambition, drive and powers of persuasion made their impact felt in the most dramatic manner. The most visible aspects of his personality – his brilliant presentations, his flamboyance, and catchy buzzwords, “the higher directions of war”, “penetrating capacity”, “arming ahead”, and his highly advanced strategic thinking – endeared him to the then minister of state for defence, Arun Singh, and Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi. What added to the impact was Sundarji’s hi-tech approach; computerised map displays from floppy disks on strategy and force levels, something that both Rajiv and Arun Singh were overly impressed by and led to Sundarji being named “the Sam Pitroda of the services”.

The most powerful aspect of Sundarji’s personality is his charisma and his command of the language which has an almost hypnotic effect on his listeners. He is an impressive figure – dashing, slim and dark-skinned, who has designed his own uniforms for the armoured corps. His speech has traces of his Tamilian ancestry but his quick-wittedness always seems to help him select the most effective words and phrases. He is also probably the most well-read man in the army. It was mainly this aspect that had such a positive impact on the political leadership.

A confidential study, obtained by India Today, on India’s defence perspectives says, “At no other time, except possibly the period just before the Indo-Pak conflict of 1971, has the Indian military and political leadership been so closely associated. Delhi’s bold initiatives in power projections, its new diplomatic aggressiveness, its euphoric confidence is obviously correlated to the new rapport that Sundarji had established with the political high

command. The evidence of that came during Operation BrassTacks, the four-phase exercise in the deserts of Rajasthan in the winter of 1986-87 and the lesser-known connecting exercises, that were the largest land exercises ever conducted any where in the world.

According to senior officers who took part in the exercise, BrassTacks was ostensibly meant to test many of Sundarji’s strategic concepts, including RAPIDS, mechanised warfare, the new equipment the army had acquired, close air support and the mobility of a massive amount of armour. Sources say that 2,400 tanks were employed in the multi-corps exercise.

But what Brass Tacks eventually led up to was a serious confrontation with Pakistan because of the huge forces involved so close to their border. Brass Tacks was an undoubted success in terms of proving some of Sundarji’s concepts on the ground – rapid movement of armour, the availability of real-time intelligence, force multipliers in the form of Mi-17 assault and Mi-25 attack helicopters – and, more vital, Sundarji’s broader concepts of dissuasive posture and deterrent capability.

However, in diplomatic and real military terms, Brass Tacks degenerated into something of a disaster. According to top-level sources in the Defence Ministry, Sundarji had convinced Arun Singh that Brass Tacks was necessary to project his concept of coercive diplomacy, in other words, signal to Pakistan that India had the muscle and the will-power to launch an offensive in India’s national interests.

Brass Tacks, in the words of a confidential report prepared for army headquarters, set out to prove that “From the evolution of political and military aims preceding a conflict to the conduct of a command-level exercise with troops involving mechanised offensive operations by a strike corps deep into enemy territory in conjunction with the air force.that clearly indicated to a belligerent and recalcitrant neighbour, the power and strength of India’s armed forces.”

The report, for obvious reasons, falls short of disclosing the actual scope of Sundarji’s plans which, according to sources in the Defence Ministry, was to provoke Pakistan into some action which would then give the Indian Army an excuse to launch its own offensive. This offensive was code-named Operation Trident. According to a forthcoming book by defence analyst, Ravi Rikhye, which has an authoritative account of Brass Tacks: “Trident called for an attack, with Skardu (in Pakistan Occupied Kashmir) as the first objective and Gilgit as the second.”

Rikhye writes: “Brass Tacks was originally intended as a massive strategic deception to focus Pakistani attention on Sind while India went for the northern areas.” The problem, senior commanders said, was that Pakistan continued with its own exercises and stayed mobilised. This was why the initial attempt by Sundarji and Arun Singh to create a suitable war scare failed. On December 18, 1987, an extensive briefing was provided to national editors by Sundarji and Arun Singh that sought to convey the impression it was Pakistan which had mobilised its forces on the border and the country should be prepared for the worst.

The briefing led to strong protests from the Foreign Ministry because it had not been fully informed. As a senior cabinet minister later told India Today: “I am sorry to say that the man (Sundarji) almost led us to war. The prime minister had not been adequately briefed.” It was only after the Soviet and American ambassadors frantically called on the Foreign Ministry and informed them that according to their own intelligence information the Pakistanis had no hostile intentions, the Indian Government decided to de-escalate.

It was not only Brass Tacks that had caused concern in Islamabad, Washington, Moscow and even Beijing. There was another exercise called Exercise Checker Board and its extension, Operation Falcon, in the eastern sector. This involved three divisions moving to positions around Wandung in Arunachal Pradesh and the air-lifting and air-maintenance of some 21,000 tons of equipment 80 km ahead of existing road heads. As a senior commander noted: “We were literally trying to take on China with no logistical support except air-Maintenance.”

But Sundarji’s supporters say he cannot be blamed for the brinkmanship, and that the political leadership must have encouraged the aggressive posture.

As the confidential report states: “The projection of India’s powers by political initiatives was enhanced by Sundarji’s capability to translate these into military aims and objectives through the higher direction of war.” But more than that was the fact that in diplomatic terms, New Delhi wound up with egg on its face. It appeared as if New Delhi was prepared to create an incident but, when the crunch came, was forced to back down.

It was in the wake of Brass Tacks that Sundarji lost the political clout he had managed to build up. It was also the time when relations between Rajiv and Arun Singh started to sour. But Brass Tacks also taught other serious lessons to the army and revealed the flaws in Sundarji’s concepts of warfare.

Says a serving corps commander: “The Brass Tacks concept of war is for the year 2000 and not for present needs. The integrated concepts of ground-air battles, air assault divisions with tanks moving for nine hours a day cannot be carried out with our present capabilities. It is only a peek at the future with the consequent strain on resources and equipment. Brass Tacks may have given individual soldiers and units of the Indian Army an opportunity to prove their staying power and stamina and instill a sense of pride. But it damaged a lot of the armour.”

According to armoured corps officers, because of the desert conditions, the distance and the speed at which they travelled, the damage caused to the tanks in terms of engines and tracks and other components was extensive. But this was again a reflection of Sundarji’s personality and flamboyant style.

Ever since Sundarji, the infantryman, took over the armoured division, his credentials for the job were questioned by armoured corps officers. This instilled in him an overriding desire to prove himself. Says a senior armoured corps officer: “In order to counter criticism of his personal ability, Sundar spent enormous amounts of time reading up on mobile warfare, driving tanks all night and up sand dunes at nearly 90 degrees and firing tank weapons. It was these macho concepts that he introduced into exercises such as BrassTacks.”

Despite his loss of political clout, Sundarji’s legacy was already well entrenched in South Block. This was reflected not only in the subsequent – and ongoing – battle in Siachen but also in the aggressive posture adopted against the Chinese during Exercise Checker Board and Operation Falcon. What mitigated this posture was the fact that it displayed contradictions in foreign policy.

BrassTacks took place when New Delhi was making moves to normalise relations with Pakistan; Checker Board and Falcon when the seventh round of border talks with China was under way and a package deal was on the verge of being worked out. Says a senior officer in army headquarters: “We have forced the Chinese into a more rigid and warlike posture in the North-east, something the political leadership is now trying to assuage by Rajiv’s proposed visit to Beijing later this year.”

This again is a reflection of how completely Sundarji had won over the political leadership. Says Stephen Cohen, the renowned American security expert and author of classics on Indian and Pakistani armies: “Of all the generals I have met. in South Asia and elsewhere. Sundarji stands out for his professional and intellectual ability to apply modern science to the art of warfare.” But what surprises Cohen the most, he says, is “the fact that the rise of Sundarji coincided with the rise in Indian military activism, as evident from Punjab to Checker Board and Sri Lanka. No other Indian general has had such impact.”

The main thrust of Sundarji’s argument has been that the Indian Army is capable of taking on Pakistan as well as China at the same time. At a meeting of the Cabinet Committee on Political Affairs where he propounded this theory, a senior cabinet minister was forced to admonish him openly saying: “This warlike talk of taking on two powerful neighbours is not going to get us anywhere.” And Lt-General Thomas says: “I don’t think all this talk of taking on Pakistan and China is productive. For one thing, Pakistan is stronger than ever before. Our army is spread thinner and Punjab is not the stable base of operations it once was.”

That, in fact, is one of the major criticisms levelled against Sundarji: that by his hawkish posture he has allowed the army to be spread too thin, especially after Operation Pawan in Sri Lanka, which has tied down 80,000 troops, including the 36th and 54th Divisions, the only effective strategic reserves in the Indian Army. This is even more so since the troops in

Sri Lanka have been taken out of the strategically vital Western Command. As most officers and other ranks now complain: “The Indian Army is a tired army.” Soldiers have not been reverted to their basic formations for six months. They cannot even receive mail from home when they are away. Normally, an infantry battalion spends three years in a field area and two-and-a-half years in a peace station. “But today.” says a division commander from Central Command, “because the army is over-stretched, a battalion is getting only about 15 months in peace areas and family accommodation is available only for 14 per cent of them.”

Adds a subedar major from a Rajput Regiment who had just been posted to Jaipur after just two months in his previous posting in Ladakh: “My battalion is in Chushul. I’m going to Jaipur and God knows how soon I’ll be moved out again. I haven’t seen my family for almost two years now.” Significantly, the Chinese have taken careful note of this phenomenon; the latest propaganda broadcasts from Beijing monitored by the Defence Ministry have stated: “We faced an unprepared Indian Army in 1962 and now we face an exhausted Indian Army.”

The best examples are Siachen and Sri Lanka. In Siachen, even though troops are rotated, the rigours of the freezing climate, the battle conditions, the problems of supply and communications and the casualties (an estimated 250 a year) tax the human spirit to unbelievable levels. In Sri Lanka again, troops have been ordered to mobilise overnight and thrown into battle within hours of landing in alien territory with no knowledge of the terrain or even a comprehensive briefing on the situation.

Senior army officers insist that Sri Lanka was another case of Sundarji’s style of rushing into things too fast with an eye to impress the political leadership and in support of his theory of the higher direction of war – in this case, an aggressive assertion of India’s military . and regional clout. Though Sundarji stoutly defends his decision, it is obvious that Operation Pawan. like Operation Bluestar. was launched without adequate intelligence, with over-confidence and a clear underestimation of the motivation and resolve of the enemy.

Though once again Operation Pawan gave Sundarji an opportunity to test out many of his strategic concepts on the ground-the special forces para-commandos and the air assault division-the original estimates that it would be a quick, surgical operation went hopelessly awry. As more than one officer has remarked: “This was again an example of his personality and ambition. It was his desire to please the political leadership and win back some of his lost glory and clout. Other generals would not have displayed the same alacrity.”

They point to Maneckshaw’s stand during the Bangladesh crisis in 1971 when he firmly told Mrs Gandhi that he needed time to prepare before going into what was then East Pakistan. He finally led the army in more than a month after Mrs Gandhi asked him to. Says Air Commodore Jasjit Singh: “There would have been less foul-ups and it would have been a better operation had there been more time. But one doesn’t really know what compulsions and imperatives Sundarji was working under.”

That is perhaps his greatest flaw. His monumental ego and ambition seldom inspire him to take advice or exercise greater caution in such situations. It is for this reason that Sundarji’s legacy can never be fully and realistically analysed. He was, perhaps, a man ahead of his time, a 21st century general dealing with a 20th century army. In the bargain, many of his innovations and characteristics have been roundly criticised. These include:

- His disdain for detail, for administration and logistics. The best example is Brass Tacks where the armour moved so rapidly that the back-up. supply and support systems were left far behind.

- The command-staff stream which changed the traditional structure for staff and field appointments and caused considerable resentment.

- The abolition of the traditional commanding officer (CO) of the regiment who was always a Lt-colonel. In the Indian Army, the CO was the inspiring force, a leader that every jawan in the regiment looked up to as a father figure. He knew the names of every soldier and was the man who led them into battle. Under Sundarji’s policy of upgrading the rank structure, regiments have one full colonel as the CO and two Lt-colonels. This has reduced the rapidity of decision-making and accountability.

- His obsession with desert warfare, mobility and mechanisation has downgraded the infantry, the traditional backbone of the army. Not one of the key organisational posts of principal staff officers (PSO) at army headquarters is held by an infantry officer. When Sundarji created the Mechanised Infantry Division, he took the most famous and heavily-decorated battalions of the Indian Army, wiped out their individual identities and incorporated them into the division. The Ist Sikhs, the battalion with the most Victoria Crosses, became just another numbered battalion of the division.

- His reorganisation of the rank structure has made the army top-heavy-positions that were previously held by brigadiers are now filled by Lt-generals.

- His lack of man management at the crucial lower echelons. His over-concentration on strategies and concepts has resulted in his hardly visiting the troops under his command, a key factor in terms of morale and inspiring the jawans.

- The pace at which he introduced hi-tech into the army was perhaps faster than the ordinary soldier could absorb.

It is precisely this kind of blitzkrieg approach that has diluted the total impact of Sundarji’s legacy. There is no question that he is an exceptionally brilliant strategist, a man with a modern mind who made the army think in modern terms. He has undoubtedly laid the foundations of the acquisition of state-of-the art weapons systems, equipment and technology.

Says Air Commodore Jasjit Singh: “Sundar had the right approach. He wanted officers to come out and talk, to write and discuss. But he cannot be held responsible for how others coped with this. He spelled out what he wanted. It was certainly up to the officer corps to respond to his initiative. Was there something wrong with his approach? Or were people not motivated enough to respond?”

The best answer perhaps comes from a corps commander who is otherwise critical of Sundarji’s overall legacy: “His greatest contribution is that he generated thinking and generated studies both useful and relevant. He got the army thinking about equipment and resource needs it would have 25 years from now. In two years, this is a great achievement and no other chief could have pulled it off. But even while he got the army thinking about the year 2000, the implementation of tomorrow’s concepts in today’s atmosphere has got people confused.” Adds Lt-General Thomas: “There’s no question that Sundarji should have strong, level-headed PSOs who can focus his attention on the fact that while it’s all well and good to plan for a war in 2000, there could easily be a war in 1989.”

In the final analysis, Sundarji’s legacy must also be viewed against the timing and coincidences of his tenure. He came in shortly after Rajiv was elected prime minister and the euphoria over hi-tech equipment and computerisation was at its peak. Like Rajiv and Arun Singh, Sundarji was a man with modern views and that helped him to push through many of his innovations with little or no resistance.

But it also gave him the kind of political clout that no other army chief has ever had. Apart from which, none of his predecessors – Vaidya, Krishna Rao, T.N. Raina or even Maneckshaw – dared to fiddle with the traditional structure of the army or had the kind of advanced and sophisticated conceptual military mind that Sundarji does.

The result is that the army today is an army in transition. In the next 15 years, it will be rebuilding its technological base and totally retraining its manpower in line with the thrust that Sundarji gave it. The ultimate irony is that during this period of transition the army cannot afford, for the next decade, to indulge in the kind of warlike scenarios that Sundarji was so obsessed with.

************

Item 2:

The Gnn that can kill at four years’ range

by India Correspondent, Economist, Sept 9, 1989, p. 35-36.

When the Indian government signed a contract in early 1986 with the Swedish company Bofors to supply $1.4 billion worth of 155mm howitzers to the Indian army, Mr Rajiv Gandhi little realized that he might have caused his own and his party’s defeat in India’s next election. That election is now no more than three months away, and the prime minister hears the whistle of the approaching shell he himself fired all that time ago.

The Bofors howitzer is an excellent gun, which is serving India well. A lieutenant in the Indian army just back from the snowy wastes of the Siachen glacier up in the Himalayas, where India and Pakistan have been fighting an undeclared war for the past four years, tells your correspondent that earlier this summer it hit Pakistani targets, at extreme range, over the top of the mountains, with ‘pinpoint accuracy’. It was grand for ‘shooting and scooting’: it could thump away at the enemy and then move to a new position in less than the two minutes it took Pakistan’s American-made artillery-finding radar to locate it and direct the Pakistani guns on to the place where it had just been.

Money, not guns, is Mr Gandhi’s trouble. Ever since 1987, the year after the contract was signed, the story that Bofors had promised and paid huge kickbacks to unidentified Indian middlemen has surfaced with embarrassing regularity. Each time it has come up, many Indians have felt that it confirms their worst fears about corruption in the ruling Congress Party. As time has gone by the possibility has been raised that, even if Mr Gandhi did not take any of the kickbacks himself, he certainly knew about them and condoned them. Now comes the most damaging blow yet to his credibility.

General Krishnaswami Sundarji was the army’s chief of staff in 1986, and he endorsed the decision to buy the Bofors gun. But he has just declared, in an interview with the magazine India Today in which he expressed his relief at getting the matter off his chest at last, that he had strongly advised the government to threaten Bofors with the cancellation of its contract if it did not reveal the names of its ‘agents’. His advice had been ignored, he said, by the prime minister’s office.

This flatly contradicts Mr Gandhi’s assertion, which he has made more than once in the past two years, that he had thought of cancelling the Bofors contract, but had met stiff opposition from the army chiefs. What General Sundarji said sharpens the choice before the voters at the forthcoming election. They have to decide whether they will be ruled for the next five years not only by a party that is palpably corrupt, but also by a prime minister who probably has not told the truth on this important subjet. It is hard to see how Mr Gandhi and the Congress party can fail to be hurt by General Sundarji’s words.

The ordinary Indian has a strong moralistic streak. Most Indians still subscribe to values that predate the industrial revolution. For them trade is still a form of exploitation, and the charging of interest is usury. To these people, kickbacks and commissions on defence contracts amount to a betrayal of the nation. That Bofors was prepared to pay as much as 14% of the value of the contract to its ‘agents’ (and that its competitors were no doubt willing to do the same) has shocked most people. It puts a powerful new charge into the belief, long the subject of rueful gossip in Delhi’s drawing rooms, that huge commissions have been loaded on to virtually all large foreign contracts – not just defence ones – to help the finances of the Congress party.

Mr Gandhi came into office when his mother was assassinated in 1984, and handily won the ensuing election on the sympathy vote. In the following year, his popularity grew immensely because he showed every sign of wanting to make a break with the past. In March 1985 he reformed the system of direct taxation to encourage taxpayers to declare their incomes. In October of that year he ordered all ministries to eliminate middlemen in all large contracts. Two months later, during the celebration of the Congress Party’s centenary, he delivered a tirade against corruption in the party and promised to clean it up. After all this, the disappointment caused by the Bofors revelations is acute. In a country like India, its effect on the Congress party’s chances in the election could be enormous.

The opposition is counting on it. It consists mainly of a seven-party coalition called the National Front. It does not have much to offer the electorate in the way of distinctive policies. But it does have as its leader a man most Indians consider to be honest. This is Mr Vishwanath Pratap Singh, Mr Gandhi’s former finance and defence minister. He was forced out of the government, and the Congress party, in 1987 because he had started an inquiry into kickbacks allegedly paid by a West German submarine-building firm in 1981, and into illegal accounts held by Indians in banks abroad.

Mr Singh has been campaigning vigorously for the past two years on the corruption issue. With the Congress party’s help he may at last have made his point stick. Untill as recently as July it had seemed that Mr Gandhi was managing to divert attention from the subject. He had lowered the voting age from 21 to 18. He had also introduced a constitutional amendment to make elections to village councils mandatory, thus in effect creating a third tier to India’s federal democracy. These were popular measures.

He then undid all that good work. First, he tried to suppress the auditor-general’s report on the defence ministry, which made some critical observations about how the Bofors gun had been chosen in preference to its French competitor. He then allowed members of his party to attack the auditor general in parliament. This gave Mr Singh the opportunity he had been looking for. The opposition resigned en masse from parliament. Mr Singh reinforced his anti-corruption credentials by announcing that, if he becomes prime minister, he will publish the details of all large contracts awarded by the government, and will set up a national fund to cover parties’ election expenses. The creation of such a fund was the one thing Mr Gandhi had left out of the electoral reform bill he put into force at the beginning of this year.

Mr Singh is looking at the 70m new voters in the 18-21 year-old range Mr Gandhi has enfranchised. He knows they are at the most idealistic stage of their lives, and he is appealing directly to them.

************

Item 3:

Heavily shelled by Bofors’

by Edward W. Desmond, Time (International edition), Sept 25, 1989, p.12.

Few countries are more scandal ridden than India, where politicians level charges of impropriety against one another on an almost daily basis. Most scandals disappear from the papers within a few days, but a recent case has shown remarkable staying power. For 2½ years, the government of Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi has been trying to shake off allegations that $50 million in kickbacks were paid to Indian officials and others in connection with a $1.3 billion purchase of field guns from A.B. Bofors, the Swedish arms firm. But one embarrassing contradiction and revelation after another has merely set the hook of suspicion deeper. Now the Bofors case has become the unifying issue for an otherwise fragmented opposition in the national elections that are expected this winter. It has provoked unprecedented conflicts involving Parliament, the army and other institutions. Says Rajni Kothari, a leading political analyst: ‘Bofors is no longer merely the name of a gun. It has come to symbolize the corruption of a ruling elite – not only of money but of office, institutions and traditions.’

The latest episode in the Bofors drama began early this month when India Today, the country’s leading newsmagazine, carried an interview with retired General Krishnaswami Sndarji, who was army Chief of Staff at the time of the Bofors deal. Sundarji said he had told the government that it should threaten to cancel the Bofors contract unless the firm revealed who had received the kickbacks. The delay in obtaining the new guns would not harm India’s security, he said, but the scandal would undermine the ‘national honor’. Sundarji’s remarks contracted Gandhi’s claim that the country’s security would have been at risk if he had canceled the contract and thus the delivery of the guns. In response, Gandhi tried to brush aside Sundarji’s interview, saying that the government, and not the army, knew best about the country’s security.

The Bofors scandal dates from April 1987, when a Swedish radio broadcast revealed that the munitions firm had paid illegal commissions on the Indian deal. At first New Delhi denied the report as ‘false, baseless and mischievous.’ Eleven days later, Gandhi promised Parliament that once he had received information from the Swedish government, he would take ‘the hardest possible action’. But when information confirming the payments arrived in June 1987, Gandhi chose to dismiss the sums as ‘administrative costs’ and later as ‘winding-up charges.’

Even as Gandhi shifted ground, his government scrambled to prevent other governmental institutions from untangling the affair. What was perhaps the only independent government investigation was submitted in April this year but was not made public until July. The report detailed the army’s sudden reversal of favorable evaluations given to a Bofors competitor and called the reasons given for the change ‘unconvincing.’

The Prime Minister admitted in an interview last year that his image had taken a ‘beating’ in the Bofors cse. The opposition has been pounding away on the slogan. ‘It is said in every nook, Rajiv Gandhi is a crook.’ But to what extent the charges of corruption are swaying voters may be another question. A large number of citizens have benefited from the country’s current annual growth rate of 9% and may be disinclined to vote against the party in power. At the same time, however, many prominent Indians are worried about the damage that the Bofors affair has caused to national institutions. Says Jaswant Singh, an opposition Member of Parliament: ‘What a terrible price the nation has paid for this wretched deal.’

**************

Item 4:

‘Soldier of the Mind’

by Shekhar Gupta. Indian Express, Feb.10, 1999.

Not long after retiring as India’s most talked about soldier since Manekshaw, General Krishnaswamy Sundarji had decided to become a columnist. His first few attempts were quite disastrous and we, then at India Today, had a problem. How do you tell the great general, with the ego larger than an armoured division, that he probably could not write to save his life? I was assigned to carry the bad news to him.

He was then recuperating from open heart surgery at Delhi’s military hospital. ‘So, doct,’ he asked, ‘is there still some hope, or is the patient a write-off?’ Before I could figure out a diplomatic answer he asked more directly, ‘I believe you think my writing is all bulls. So where does that leave us?’

‘I think, General,’ I said, ‘you need to be a bit more direct in your writing – just as you are when you speak.’ I then added as a smug afterthought, ‘Just come to the brasstacks quickly.’ His eyes lit up. ‘That’s it, my friend, that is the name for my column.’ His next piece was a great improvement. The column ran for a long time under the title ‘Brasstacks’.

Retiring in the controversial aftermath of Blue star, Brasstacks, IPKF and Bofors, this general tried his best not to just fade away like some others. He wrote columns, straddled the security seminar circuit, was paited larger than life on the chatterati radar screen and generally emerged as the most articular military spokesman for India’s nuclear programme.

We sparred a great deal on the circuit. He never could resist the temptation of pulling my leg over some military detail I got so horribly wrong in my coverage of Operation Bluestar even though another scribe on the beat, who happens to be a friend, had got it just right. In my book, confusing line-of-sight 25 –pounders with larger artillery was not such a big deal. For Sundar, it was an outrage, ‘that’s why you hacks are such big bores with low caliber’, he would say to rub it in. But he himself had plenty to be defensive about. Both Bluestar and Operation Pawan (Sri Lanka) were tactical disasters. It may be unfair to suggest that you could spin a sequel to Norman Dixon’s Psychology of Military Incompetence around these two operations, but you could possibly pen a Psychology of Military Arrogance. Sundar was a grand strategist, a visionary, who was better off moving mechanized divisions and field armies in wide open desserts, or, better still, on Ops Room maps and sand models. He did himself injustice by getting directly involved in these operations. That is why it is so tragic that the legacy of India’s most brilliant military commander will forever be marred by his record in what were at best battalion-sized operations.

Students of Indian military history will quibble endlessly over whether Sundar was ahead of his times, or behind them. The truth, perhaps, is both. In terms of his approach to technology, mechanization, mobile warfare, he was way ahead of his times. He did sometimes admit he had over-reached himself with Brasstacks. But, he argued, that was the only way he could get his field commanders to think big. Most of them had no experience of seeing a formation larger than a division move. Brasstacks had entire field in maoueuvre – with live ammunition to boot, and so what if it brought India to war with Pakistan?

‘You have this typical ****cowardly Indian thinking’ he would say. But was he so impatient because politically he was a couple of decades behind times. This was the post-conventional warfare world where nations preserved or enhanced their national interest by waging or resisting low intensity conflict rather than Pattonesque set pieces. Where diplomacy, politics and then, increasingly, economics became the crucial prongs in strategic thinking. For Sundar, Low Intensity Conflict was such a bore – he dreamed of a heli-borne assault division and even designated one to be trained for the role. Almost immediately he had to endure the embarrassment of seeing its crack fighting units come unstuck under LTTE’s deadly sniper fire and improvised explosive devices in the jungles of Jaffna.

He had his critics within and outside the army. The friendlier ones dismissed him as a well-meaning romantic with little relevance to his time. For them, Brasstacks was his nostalgia for great old days of set piece battles, probably even an effort to create one to test his pet theories on the battlefield, in the Clausewitzian fog of war. For the more vicious, he nurtured a grand-political ambition and Brasstacks, with a resultant war and victory against Pakistan, was his shortcut to political power. They do the General great disservice.One with such dispositions and careeristic outlook does not question the prime minister of the day on the acquisition of his favourite toys ^ Bofors in this case – nor does he follow it up with a kiss and tell not long after.

Sundar hated the ‘dirty little wars’, the Golden Temple, Jaffna, Brahmaputra Valley and so on. But that is all he was fated to fight and not very successfully. It was probably a combination of this bitter failure and the belated realization that the days of Conventional Warfare were over that brought him in close touch with the nuclear lobby. Soon enough he had become its leading light.

We spent a week together at Salzburg, the usual suspects from India and Pakistan, on the conflict resolution circuit and in the summer of 1994 I got a chance to get back at Sundar. Why, I asked, was it so that the most prominent nuclear hawks in India were from the South? Didn’t it sound uncannily like a diabolical Tam Brahm [Note by Sachi: This is a pejorative abbreviation for ‘Tamil Brahmin’] conspiracy to get Punjabis on both sides of the border to incinerate each other so the kings of Kumbakonam could role the subcontinent forever? But to be fair to him, even on the nuclear issue, Sundar ws by now evolving a doctrine of his own – ‘more is not needed when less in enough’. He wanted India to develop a limited nuclear deterrent, without entering into any nuclear race. It does not matter if the Pakistanis have a hundred weapons and we have ten. This is more than enough to finish Pakistan, or deter China, so why waste money on building a Stalinist arsenal was his argument. Today, he would have been happy to sign the CTBT, engaged in FMCT and a regime of confidence building measures and mutural restraint with Pakistan. He would have also wanted a nuclear India to cut force levels, lower defence spending, mechanise, computerize more and plunge headlong into the Revolution in Military Affairs. Who knows he may have been writing the obituary of the tank, or the mechanized division, his most visible contribution to his army.

Sundar had a cutting tongue and very little discretion when provoked. At another India-Pakistan seminar he fidgeted uneasily, visibly irritated as Pakistan participants took turns at giving vastly exaggerated numbers for Indian troops in Kashmir. Then a former Pakistani army chief put the number at seven lakhs and Sundar intervened. ‘The only way you get to that number, general, is if you count the limbs, multiply by four and divide by two,’ he said. His Pakistani counterpart looked a bit sheepish.

Much has been said of his peculiar equation with Rajiv Gandhi and Arun Singh, his de facto defence minister. It is possible that one day Arun Singh would throw more light on this, give it a perspective that he owes to the memory and legacy of his favourite general. In one way, however, the general had his timing right. He took over the reins of the army under the political leadership of two, young, techno-savvy political leaders. He did the rest – his domineering personality kept the babus at bay. He certainly would not have survived a Mulayam Singh Yadav, a George Fernandes or Ajit Kumar. Or vice versa.

Sundar died at just 69, at an age when great marshalls were leading great armies into battle in the Great Wars. His death did not merit more than a single column mention – below the fold on many front pages – yesterday morning. But, surely, there will be many obituaries written. And one question all these facile military analysts and historians will ask – or answer – is, what do we remember General Krishnaswamy Sundarji for? Hopefully, the answer would be Brasstacks rather than Bluestar or Jaffna.

This takes me to August 14, 1990, Pakistan’s Independence Day is Islamabad and just a week after the encounter with Sundar at Delhi’s military hospital. At the official reception I buttonholed General Mirza Aslam Beg, the controversial Pakistan army chief who had just held Exercise Zard-e-Momin (The Strike of the Faithful). Or, more accurately, his counterstrike. The basic premise of the exercise was, that in the next war Foxland (as India is referred to in Pakistani wargames) breaks through in the initial phase and the Pakistanis then counterattack and envelope the invader. It was the first major Pakistani exercise that was so defensive in nature, where survival, rather than an all-out victory, or the liberation of Kashmir, was the main objective. Surely, Brasstacks and the scary vision of 3,000 Indian tanks rolling down the desert, threatening to bisect Pakistan had changed a military mindset rooted in medieval history and thrust-and-parry purposelessness of India’s armoured strike forces in 1965 and 1971.

‘So does your publication write a lot about defence and security?’ Beg asked, making polite conversation.

‘Yes’ I said, and soon we will begin to run Sundarji column.

‘What is it called?’ Beg asked.

‘Brasstacks’, I said.

The temperature dropped a few notches. This general’s eyes did not exactly light up in delight. Would you still have any doubt as to Sundarji’s real legacy?

**************

Item 5:

Warrior as scholar

by Manoj Joshi, India Today, Feb.22, 1999, p. 33.

Shortly after Pokhran II, General (retd) Krishnaswami Sundarji had a visitor, a senior member of the team that carried out the Shakti tests. By this time the general was seriously ill, struck by a disease that deprived him of movement and speech. ‘He knew of the news, of course,’ says the official, ‘but when I recounted it, he gripped my hand strongly and then gave me a vigorous thumbs up.’ Behind the special gesture and the elation lay more than two decades of history in which Sundarji single-mindedly got the tradition-bound Indian Army to think about the consequences of nuclear weapons. His Combat Papers I and II, published when he was commandant of the College of Combat in Mhow in 1980-81, are considered a classic exposition of the army’s thinking on the subject which he was to revisit in his novel Blind Men of Hindoostan – a suggestively fictional account of his experiences – in 1993 and in his columns in newspapers and magazines, including India Today.

This would have been achievement enough for a man, but not for Sundarji, the gregarious, fun-loving Tamil Brahmin – or Tamil-Panjabi, as a friend described him. He packed so much into his life that it becomes difficult to decide where precisely his legacy to the armed forces lies. Chief of Army staff Ved Prakash Malik puts it simply. ‘He introduced professionalism into the army,’ he saids. ‘We’re today no longer a ceremonial force, but an army ready for modern war, led by a thinking leadership.’

Sundarji shot into prominence as the commander of the force responsible for Operation Bluestar in June 1984, an episode that both he and the country lived to regret. Less than two years later, he was appointed the chief of army staff and in his tenure, he led the army in a series of actions about which history’s verdict has been varying – Exercise Brasstacks, Operation Falcon in Sumdorong Chu, Arunachal Pradesh, and Operation Pawan – the commitment of Indian Peace-keeping Forces in Sri Lanka.

Sundarji’s place in history will probably rest on the lesser-known Operation Falcon. Spooked by the Chinese occupation of Sumdorong Chu in 1986, Sundarji used the air force’s new air-lift capability to land a brigade in Zimithang, north of Tawang. Indian forces took up positions on the Hathung La ridge, across the Namka Chu river, the site of India’s humiliating 1962 defeat and manned defences across the McMahon Line. Taken aback, the Chinese responded with a counter-build-up and in early 1987 Beijing’s tone became ominously similar to that of 1962. Western diplomats predicted war and prime minister Rajiv Gandhi’s advisers charged that Sundarji’s recklessness was responsible for this. But the general stood firm, at one point telling a senior Rajiv aide, ‘Please make alternate arrangements if you think you are not getting adequate professional advice.’ The civilians backed off, so did the Chinese.

By then the baleful star of the Bofors scandal had arisen and taken its toll on Sundarji’s strongest supporter in the government, minister of state for defence Arun Singh. For two years a cloud of suspicion hung over Sundarji as well. After all, he was the man who had revised th army’s priority list and plumped for the Bofor’s gun. But the cloud dissipated when Sundarji revealed (India Today, September 15, 1989) that he had recommended that the deal he scrapped, if that was the only way to get Bofors to reveal the names of recipients of kickbacks. A man on the take would hardly have recommended that course.

Sundarji has been known as the ‘thinking general’, a somewhat trite description of the man whose main contribution, according to vice-chief of army staff Lt-General (retd) K.K. Hazari, was to change the ‘traditional infantry-oriented mindset of the army’. The comment underscores the sum of Sundarji’s professional life.

Commissioned into an orthodox infantry regiment. Sundarji’s innovative approach became a byword in the army. He became computer-savvy early in the silicon era. As a result, in the late ‘70s, General (retd) K.V. Krishna Rao, then deputy chief of the army staff, picked him to be part of a small team to study the reorganization and modernization of the army. This led to the creation of ‘machine-rich’ divisions that became the mainstay of the army. Sundarji took this forward in the ‘80s to shape the army’s perspective, the Army Plan 2000, which outlined a new mobile strategy based on tanks, firepower and enhanced communications. In the light of Pokhran and the dawn of the information-technology age, the army is now revising this plan.

Sundarji has passed away, but everyone in the army knows that his spirit resides in the living, working and thinking army that he has left behind.

**************

Item 6:

Milestones

by Hannah Beech, Time (Asia edition), Feb.22, 1999, vol. 153, no.7.

DIED. Krishnaswamy Sundarji, 70, ambitious Indian army chief, whose long military career was haunted by his stewardship of the bloody 1984 raid on Sikkism’s holiest shrine; in New Delhi. The storming of the Golden Temple, which left 500 people dead, was not Sundarji’s only foray into controversy: in 1986 he provoked neighboring Pakistan to hold showy military exercises along the volatile border and later committed India to a peace-keeping quagmire in Sri Lanka.

**************