We Enabled Genocide, but the Elite Committed It

by Anita Isaacs, ‘The New York Times Room for Debate Blog,’ May 19, 2013

Anita Isaacs is a political science professor at Haverford College. She has researched and written about Latin America extensively.

The United States was chiefly an enabler of genocide in Guatemala. It planted the seeds for decades of violence in Guatemala when it eagerly declared the nation’s social democratic president, Jacobo Arbenz, a communist.

“I am definitely convinced if the president is not a communist,” the U.S. ambassador, John Puerifoy, said in December 1953, “he will certainly do until one comes along.” Five months later, the C.I.A., worried as much about the nationalization of United Fruit Company lands as the infiltration of Soviet power, toppled Arbenz in a coup.

Enraged by the U.S.-backed dictatorships that followed, unionists, students and dissident military officers took to the hills in the early 1960s to fight to resume the Arbenz reforms.

The U.S. turned a blind eye to the upper class’s uniquely virulent racism that permitted slaughter in the name of anticommunism.

The U.S. government also provided the Guatemalan armed forces with a pretext for repression by establishing a national security doctrine that justified brutality in the interest of eradicating leftist subversion. It armed and assisted the military. It trained Guatemalan officers at U.S. military schools and deployed green berets to Guatemala during the 1960s.

By the early 1980s when the Mayan Ixil became victims of genocide, the United States had formally suspended military assistance. Though more preoccupied with combating leftist threats in El Salvador and Guatemala, aid trickled through to the Guatemalan army and President Reagan lifted the ban on the sale of military parts and equipment during the Ríos Montt administration.

In choosing to do so, the United States deliberately turned a blind eye to the Guatemalan genocide. The Reagan administration publicly supported army claims that guerrillas rather than soldiers were perpetrating atrocities and tried to polish the tarnished image of the Ríos Montt regime, encapsulated by Reagan’s claim that the general was being given a “bum rap.”

That being said, blaming the Guatemalan military and the United States only goes so far in explaining the genocide. National security doctrine excused repression by dictatorships throughout Latin America from the mid-1960s onward, yet it was only in Guatemala that repression constituted genocide.

A complete explanation of the genocide must account for the puppet master role played by Guatemala’s oligarchy. More powerful and intransigent than their Latin American colleagues – Guatemalan elites had little trouble enlisting the military in a ferocious struggle to preserve their stranglehold on political and economic power. In further contrast to its neighbors, Guatemalan society was (and remains) profoundly racist, fearful of the indigenous majority that it has continually dehumanized. That racism let the elite-military alliance use anticommunist counterinsurgency principles to justify the extermination of Mayan peoples and communities.

“Why do you ask why Indians were killed?’’ a member of the oligarchy once asked me. “A better question is why didn’t we kill more Indians?”

It was not an uncommon sentiment among his peers.

“I don’t feel anything toward the victims,’’ a defense lawyer in the Ríos Montt trial said, “why should I?”

————————————

Genocide in Guatemala: The Conviction of Efraín Ríos Montt

by Binoy Kampmark, ‘International Policy Digest,’ New York, May 13, 2013

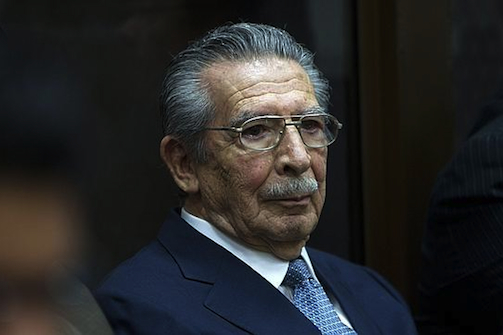

Efraín Ríos Montt was convicted by a Guatemalan court for his participation in crimes against the Mayans from 1982 and 1983. Image via abc.es

It has been hailed as the first conviction for genocide of a former head of state in his own country, and certainly the first of a former Latin American strongman. Former Guatemalan dictator Efraín Ríos Montt was convicted by a Guatemalan court on Friday for his participation in crimes against the Mayans during his rule in 1982 and 1983. Montt’s sentences were steep: 50 years for genocide and 30 for crimes against humanity.

As ever with genocide, evidence of an intentioned plan to destroy a race had to be shown. The three-judge panel led by Yassmin Barrios was satisfied that the definition had been made out, finding that there had been a clear and systematic plan to exterminate the Ixil people. Prosecutors allege that up to 1,700 of the Ixil Maya were killed, in addition to torture, rape and the destruction of villages. The acts had occurred as part of a policy of clearing the countryside of Marxist guerrillas and sympathisers.

The heart of the defence by Ríos Montt was that, as a political leader, Montt could not be held accountable for military matters conducted in a rural province some few hours northwest of the Guatemalan capital. “I never authorised it, I never signed, I never proposed, I never ordered that race, ethnicity or religion to be attacked. I never did it!” In this, Montt was echoing the sentiments of the Japanese General Tomoyuki Yamashita, who was found constructively guilty for having not stopped the massacres that took place in the Philippines.

Yamashita did have a point, and one picked up by the dissenting judges of the U.S. Supreme Court. To hold such a figure to account in circumstances of military emergency, when contact lines were severed, and the army was fighting for its survival, was a tall order. There was little evidence that those troops had acted under his orders. But Ríos Montt could hardly claim to have been Yamashita and, according to the judges, “was aware of everything that was happening, and did not stop it, despite having the power to stop it.”

The trial proved a thorough affair, featuring extensive use of forensics, the examination of mass graves and the DNA of skeletons therein. It was grim but important work, and constituted but a small part of what was a civil war of mass murder. Between 1960 and 1996, Guatemala saw conflict that claimed the lives of more than 200,000 people. Prior to that, a U.S.-sponsored overthrow of the democratically elected Jacobo Arbenz Guzman ensured that the country would be doomed to decades of bloody instability.

It is often argued that trials do not provide a means of genuine restorative healing to parties or societies. Ríos Montt will not be seen as a criminal by conservatives who feel he performed a sterling job in ensuring that the country did not fall into the clutches of left wing revolutionaries. The Cold War subtext here was that he was, if anything, heroic in holding the fort.

Besides, the current Guatemalan president, Otto Pérez Molina, refuses to accept that genocide ever took place. This may not be surprising given that Molina’s name came up in trial testimony, in which a former soldier claimed he had ordered executions while serving in the military of the Ríos Montt regime. “When I say that Guatemala has seen no genocide, I repeat it now after this ruling. Today’s ruling is not final…the decision will not be final until the moment they run out of appeals.”

There will also be consternation that the atrocities of the government, rather than those of the rebels, have featured prominently. That the former feature, however, is due to the sheer disproportionate role played by the rulers and paramilitary allies. The 1999 report by the country’s truth and reconciliation commission claimed that the government’s role in the atrocities, along with its allies, was a hefty 93 per cent.

The soiled hands of this incident are many. They did not start or stop with Ríos Montt. Will the individuals who also cast money and material the way of such regimes be held to account? A case against the higher-ups, and those complicit beyond the borders of the country may well be in the offing, though that will take time. The edifice of accountability is gradually being built. International law, as ever, takes steps not so much in strides as in awkward stumbles, but when it does reach important junctions, effects are felt. What happens with the appeal will be telling.