Reflections of the rippling effects of conflict on a Sri Lankan family, by Benjamin Dix. And an appeal for funds via kickstarter.org to complete an urgent episodic project

|

ON 12 SEPTEMBER 2008, I was told we would have to evacuate the town of Kilinochchi, the administrative headquarters of the Tamil Tigers in Sri Lanka.

The Sri Lankan Army were a few kilometres to the south and had already shelled the town, hitting a UN compound and an air strike had landed within a kilometre from my UN office causing shrapnel to rain across the courtyard.

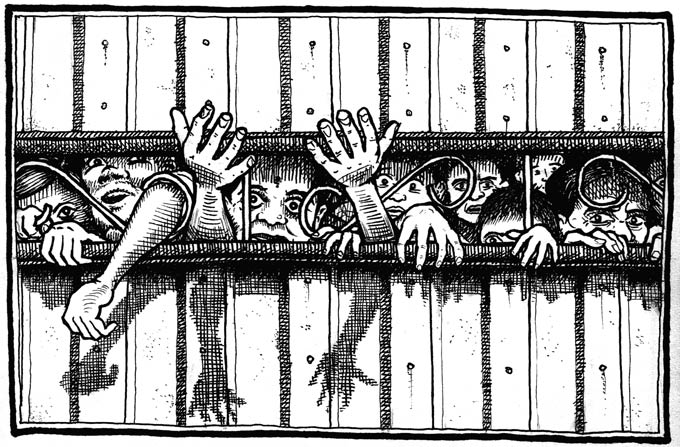

At the news of our departure, hundreds of Tamil civilians staged a protest outside our offices pleading with us not to leave. After 20 years of conflict, they understood that without the presence of international agencies and staff in the area, the army would move in with a very heavy hand, but no one predicted quite how heavy it was to be. As the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) moved further north into Vanni to continue with its operations, we (the UN) prepared to evacuate. Having worked in Vanni for nearly four years, I had made many friends with our staff and people within the community. The Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) had a strict pass system that prevented Vanni residents (including the dependents of national UN staff ) from leaving the area. I had to start the excruciatingly emotional task of saying ‘goodbye’ to friends that we were about to leave behind.

One family I visited haunts me to this day. I had known them for three years; attended their wedding, was there when their daughter was born, had eaten endless delicious dinners under the mango trees in their garden and generally considered them very close friends. They all called me ‘Tambi’ (little brother) and had treated me like a family member.

I arrived at their home at around 9 pm the night before we evacuated. The familiar, comforting night-time sounds of frogs and crickets were replaced with the deafening thuds of shells landing in the near distance. I found the family in complete despair; the husband was frantically trying to pack his tractor with essential belongings whilst his wife was huddled in the bunker, clutching their two-year-old daughter, who was having a kind of fit, instigated by an air attack earlier in the day. With the news of our evacuation, everyone was leaving the area. My friend looked me in the eye and asked, “Are you really leaving? What will happen to us?” Filled with my own confusion at the situation, I had few answers for her. The official line of the UN that we were “relocating” and would “return soon” was preposterous; the government would never allow us back after our departure. We remained quiet as I helped load the tractor; there was nothing to say. I was offered a cup of tea, and we drank in silence. I had no words to offer them; “good luck”, “stay safe”, “see you soon” seemed so ridiculous. I hugged each of them tight, squeezed the beautifully fat cheeks of the little girl and left. I stopped the car after a few minutes and threw up on the side of the road.

|

The next morning as we lined up our vehicles, many people crowded outside the compound to watch us leave. The evacuation was planned at 11 am and at 10.45 am, the air force bombed the road just 2 km from us as an act of defiance and to send the message: “leave now”. Wearing a flak jacket, helmet and inside a vehicle with all safety provisions, I drove past families wearing saris, flip-flops and sarongs. Again, I felt sick with emotions of abandonment and guilt — none of it made sense to me, wasn’t the principle to protect civilians something that I had signed up to do with the UN? I resigned from the UN the following day and left Sri Lanka disgusted at the sequence of events that had led to the situation.

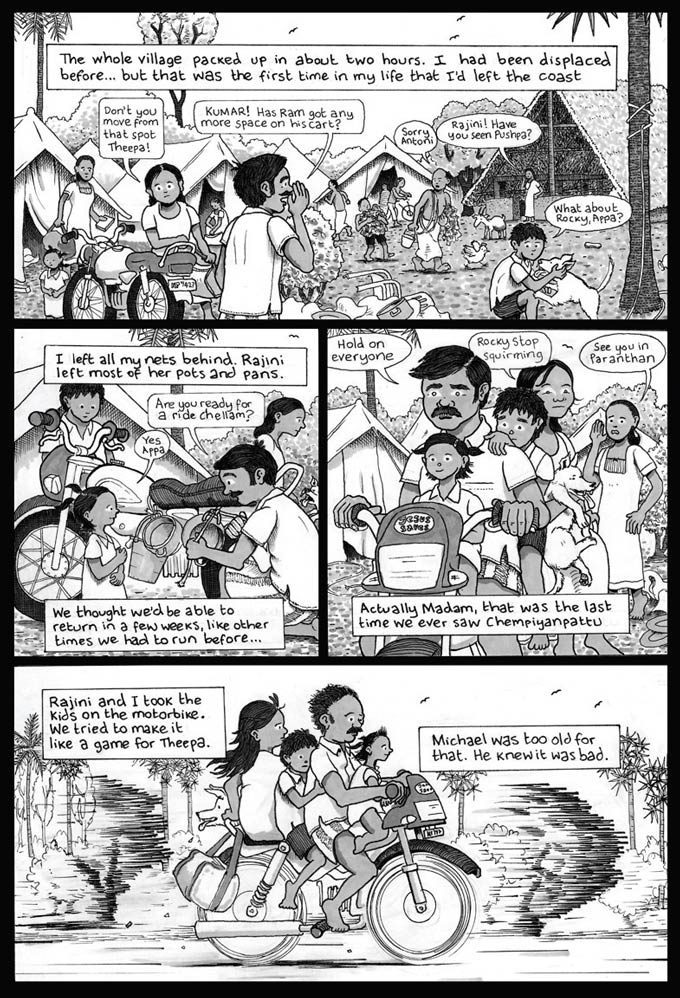

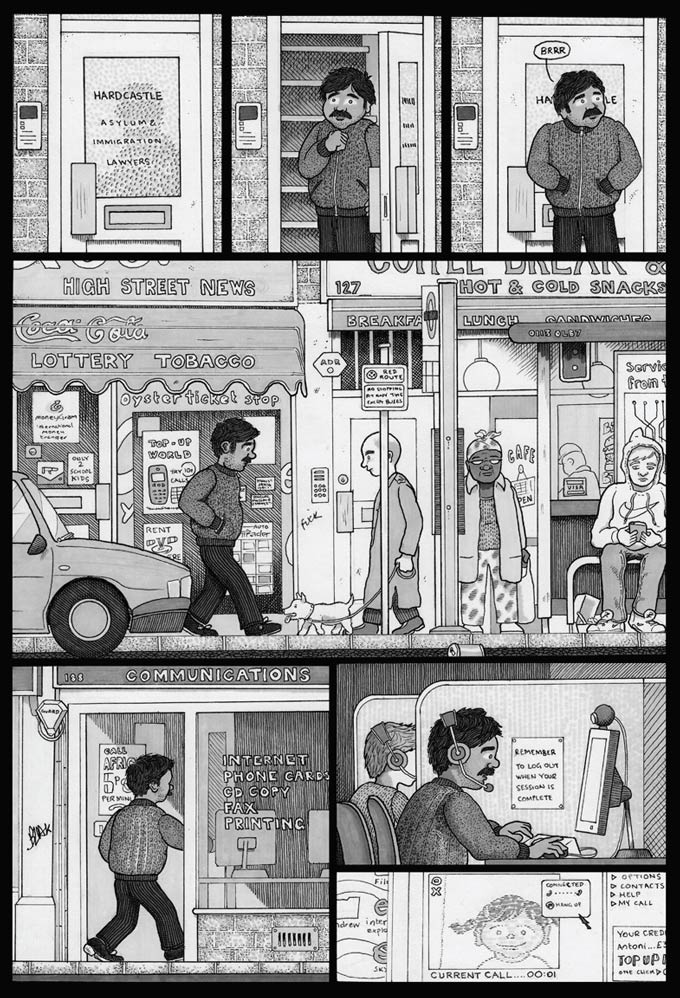

For the next two years, I kept a close eye on Sri Lanka through the very limited media coverage. I received endless messages concerning friends that had died. Then in May 2011, I received a friend request on Facebook from the husband in Kilinochchi. They had all survived and got to India. By the time I travelled to see them the husband had already left for Europe. Paying agents $20,000 (collected from family members in the diaspora) he had left his wife and daughter behind to gain asylum and then try and bring them over to join him.

|

As I sat in the small, sparsely furnished, concrete room, in a slum area of Chennai, with my old and dear friend, profusely apologising to me about the stench coming from the stagnant pond outside, and the now five-year-old girl sitting on my lap calling me Maama (uncle), still with her fat cheeks, I realised that this was the story I wanted to tell.

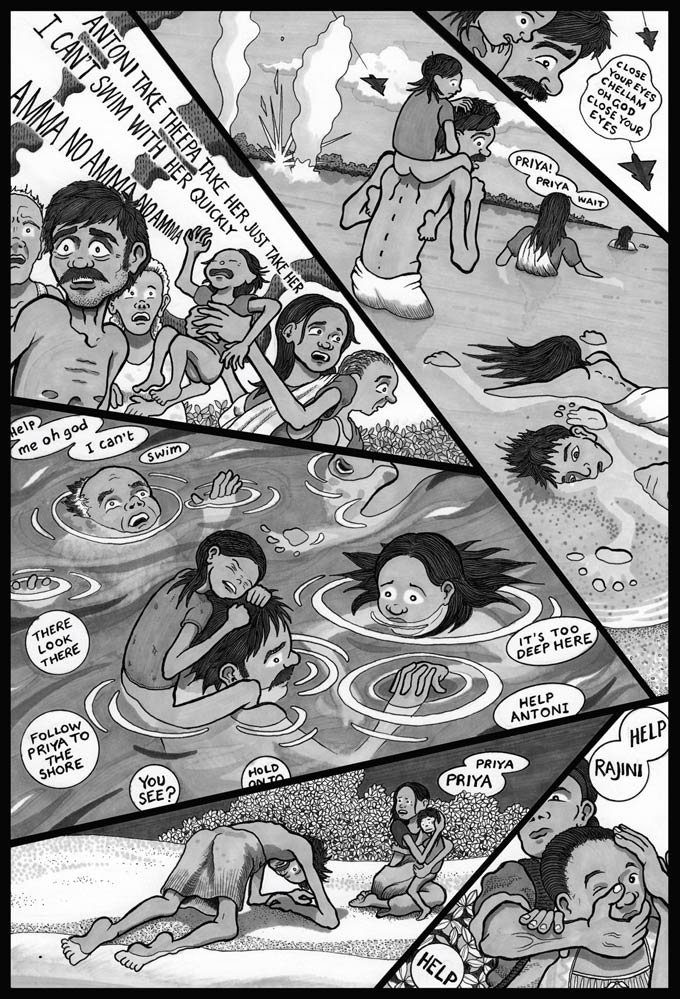

This family had survived eight months of vicious bombardment on a small stretch of beach, had seriously contemplated suicide together in the final weeks when they could not take the onslaught anymore, had lived through seven months of internment hell in the UN-built, government-run camps and then fled to India. Now alone and vulnerable in Chennai, separated for an indefinite amount of time from her husband, I was struck at the long-term effects of conflict. This family, along with so many others, will never see their ‘home’ again; they will be forever in exile.

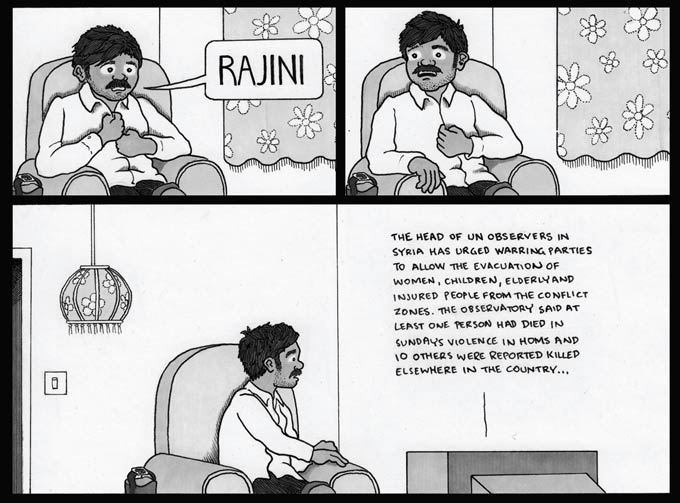

I started to collect these stories from survivors, now refugees and asylum seekers across Europe and India, and turn them into a narrative that is lived out through a fictional, Tamil family. Antoni, the husband, now in London, reflects back on his life in Sri Lanka through conversations with his asylum lawyer and his wife, in Chennai, over Skype. Illustrator and filmmaker, Lindsay Pollock and I began in 2011 to sketch out ideas for a narrative and now work closely on all aspects of the book. Through this story, I hope people will not just understand the horrific nature of modern warfare, but also the rippling effects of conflict on a family in the generations that follow.