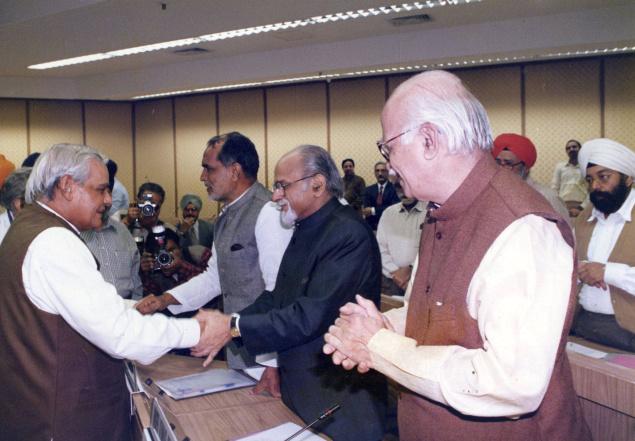

PEOPLE SKILLS: Gujral was known for his art of dealing with the trickiest of situations, and rarely spoke sharply. Photo: Shankar Chakravarty.

After days of bargaining and back room negotiations, following the collapse of the H.D. Deve Gowda-headed United Front government, Inder Kumar Gujral was formally elected on April 20, 1997 by the United Front (UF) Parliamentary Group as Prime Minister-designate. The scene of most of the activity was Delhi’s Andhra Bhavan, where Gujral had even slept the previous night after a meeting that went on into the small hours. Minutes after he was elected (those were the days when print still had an edge over TV), I seized the opportunity to shoot a few quick questions for the newspaper I then worked for. How would he persuade G.K. Moopanar’s Tamil Maanila Congress (TMC) to join his government and not merely support it from outside? How would he ensure that the Congress cooperated with the UF and not leave it in the lurch again?

Dressed in his trademark safari suit, looking relaxed, Gujral smiled and said, “I will go again and again and again. I will not take ‘no’ for an answer. We are old friends and colleagues and I will value their contribution and presence in the government.” On the Congress, his answer was almost identical in spirit: “We are trying to work out an arrangement that will be to our mutual satisfaction. Mr. Sitaram Kesri (then Congress President) and I are old friends and we have been in touch.”

In the end, the TMC did not join the government, and the Congress pulled the plug seven months later.

Friends across the spectrum

If there is a key to understanding Gujral’s life, it was that he had friends in virtually every political party, and across the social spectrum, something he makes it a point to underscore in his Matters of Discretion: An Autobiography.The “old friends” who helped him become India’s 12th Prime Minister (pipping Moopanar and Mulayam Singh Yadav to the post) included the CPI (M)’s Jyoti Basu, former Vice-President Krishan Kant (who was Andhra Pradesh Governor at the time), a group of powerful journalists and an influential newspaper group.

Similarly, when Gujral made his peace pitch to Pakistan’s Nawaz Sharif at the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation conference in Male in 1997, it was on the basis of a warm relationship cultivated over the years.

As Prime Minister, his government gave Rs.8,000 crore to Punjab to help the State recover from the ravages of militancy — it ensured the undying gratitude of the Shiromani Akali Dal (which was in power then) to this day: his son Naresh Gujral is currently a Rajya Sabha MP representing the party.

Indeed, it was his many friends, to whom he was loyal in turn, his image of being a gentleman-politician with a taste for Urdu poetry, his staunch secularism, and his brand of “pappi jhappi” diplomacy that catapulted him from thepaan-stained interiors of the offices of the New Delhi Municipal Council in the 1950s to South Block — and the ultimate prize, the prime ministership. Along the way, he became a member of Indira Gandhi’s kitchen cabinet in the late 1960s and early 1970s, ambassador to the USSR, an assignment that set the stage for his becoming foreign minister in the governments headed by V.P. Singh and Mr. Deve Gowda, and what came to be known as the Gujral doctrine — a doctrine that held that India should go the extra mile with its neighbours without expecting reciprocity, as long as it did not endanger India’s security.

Gujral’s critics have attributed his many successes to the fact that he did not have any firm convictions. While this may be partially true, he demonstrated on key occasions that he could be principled. As Indira Gandhi’s Information and Broadcasting Minister when Emergency was declared, he may not have expressed his opposition to it strongly, but he refused to brook interference by Sanjay Gandhi. He was dropped, but his loyalty to Indira Gandhi during the Congress split in 1969 ensured she did not drop him altogether — she sent him to the Soviet Union as ambassador, a job he retained even after the Janata Party came to power in 1977. Again, as Prime Minister, when the Jain Commission report accused the Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam of supporting the Sri Lankan Tamil Tigers who were responsible for Rajiv Gandhi’s assassination, he refused to drop the party, even though the price was: withdrawal of support by the Congress.

Some controversies

His prime ministership, short as it was (April 21, 1997 – March 19, 1998), was marked by a couple of controversies. Shortly, after he became Prime Minister, Bihar’s then Chief Minister Lalu Prasad Yadav faced criminal charges for embezzling funds from the State’s animal husbandry department. Gujral refused to sack him as he owed his seat in the Rajya Sabha to him; instead he transferred CBI Director Joginder Singh out. A newspaper editor from that time recalls that when he wrote an edit criticising Gujral, the latter acknowledged the criticism by telling him: “I know you are telling me I lack guts.”

On another occasion, he recommended central rule in Uttar Pradesh, but the then President, K.R. Narayanan, refused to comply with the recommendation.

I.K. Gujral was known for his skill in dealing with the trickiest of situations, and rarely spoke sharply.

But he would not tolerate any sort of foreign “interference” in India’s internal matters. So when the then British Foreign Secretary, Robin Cook, offered to mediate on the Kashmir issue, he was infuriated enough to refer to Britain as a “third-rate power nursing delusions of grandeur of its past” in a private interaction with Egyptian intellectuals during a state visit to Cairo. That remark got into print — and the Joint Secretary in-charge of the External Publicity Division, MEA, at the time was transferred out, after which his career never recovered.

Born on December 4, 1919 in Jhelum, now in Pakistan, Gujral started life as a student activist of the Communist Party of India, later joining the Congress and finally, the Janata Dal.

His parents were both in the Congress — father Avtar Narain Gujral was a member of the Pakistan Constituent Assembly. After Independence, he migrated to India and began life afresh, dying four days short of his 93rd birthday after a rich and fulfilling life.